It seems the drums of war are beating again this week in the Middle East. Perhaps they’ve never stopped beating, because humans like to fight each other. We’ve done it for eons and we’ll continue fighting forever, as long as there are resources to steal, land to fight over, religions to march for and political grievances to settle. One final line from a newspaper opinion piece on the Rwandan genocide back in the 1990s has stayed with me: “We are all Hutus and Tutsis.” It is human nature.

In order to make this third blog in #mysongscapes resonate, I had to dig out a very, very old photo album. That’s me in 1969, below. He was a Navy pilot from New Jersey based at Whidbey Island, Washington, heading off to Vietnam. His A-6 Intruder plane had wings that folded up to fit on aircraft carriers. I was his young Canadian girlfriend. He and his roommates rented a house on the Pacific Ocean.. My kid brother thought he was cool because he drove a red sports car.

We were part of a big cross-border gang whose winter life centred on the ski hills of Washington’s Mount Baker, except somehow I got through that period in my life without actually skiing (though I took a few lessons). I always joked that I had a more important job: I was in charge of brewing the glühwein back at the chalet. But while many people on both sides of the border were protesting the Vietnam War, I was hanging out with my girlfriends and the guys at the Chandelier Bar in the town of Glacier at the bottom of the mountain, dancing to our jukebox favourites Proud Mary and Bad Moon Rising by Creedence Clearwater Revival.

My pilot was shipping out to Vietnam on an aircraft carrier and maybe he would never come back. (I later learned he did return safely and became a commercial pilot.) In time I realized we weren’t really suited and I broke it off by mail before his tour of duty ended. So that was that. And life went on.

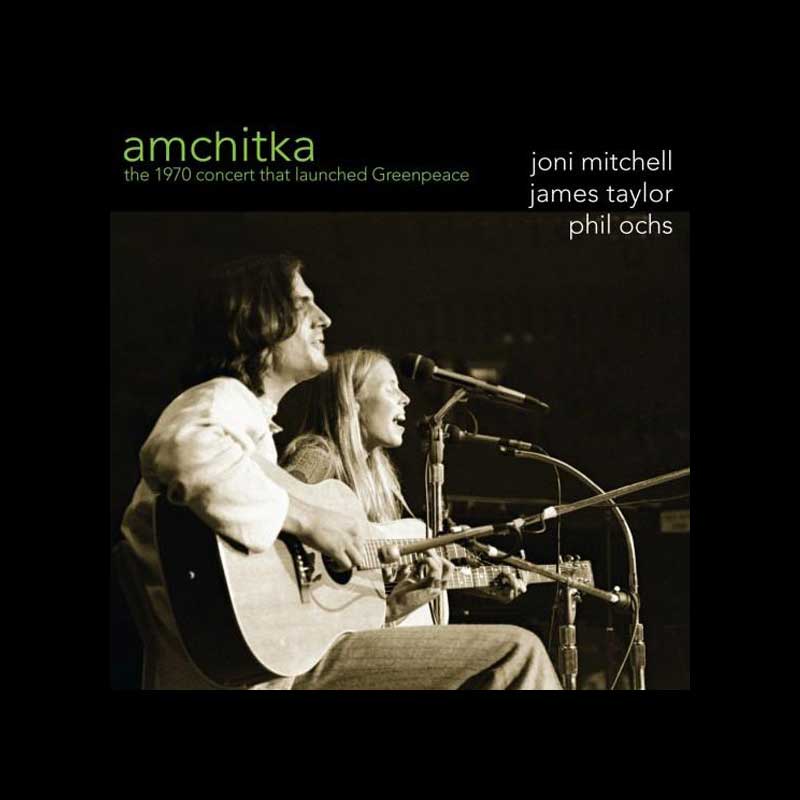

The closest I got to any meaningful protest in those days was going to an October 1970 Greenpeace concert in Vancouver to protest American nuclear testing at Amchitka. Joni Mitchell was the lead performer with her then-beau James Taylor.

Another young singer, activist Phil Ochs performed his own protest song that night: “I Ain’t Marchin’ Anymore”. It was a litany of American battles and wars through the ages. I already owned his fourth album Pleasures of the Harbor, from 1967, which included a scathing song about the social apathy that surrounded the 1964 Kitty Genovese stabbing death in New York. Sadly, Phil Ochs would take his own life in the grip of bipolar disorder five years later.

I AIN’T MARCHIN’ ANYMORE, Phil Ochs (1965)

Oh I marched to the battle of New Orleans

At the end of the early British war

The young land started growing

The young blood started flowing

But I ain’t marchin’ anymore

For I’ve killed my share of Indians

In a thousand different fights

I was there at the Little Big Horn

I heard many men lying

I saw many more dying

But I ain’t marchin’ anymore

It’s always the old to lead us to the war

It’s always the young to fall

Now look at all we’ve won with the saber and the gun

Tell me is it worth it all

For I stole California from the Mexican land

Fought in the bloody Civil War

Yes I even killed my brother

And so many others

And I ain’t marchin’ anymore

For I marched to the battles of the German trench

In a war that was bound to end all wars

Oh I must have killed a million men

And now they want me back again

But I ain’t marchin’ anymore

For I flew the final mission in the Japanese sky

Set off the mighty mushroom roar

When I saw the cities burning

I knew that I was learning

That I ain’t marchin’ anymore

Now the labor leader’s screamin’ when they close the missile plants

United Fruit screams at the Cuban shore

Call it, “Peace” or call it, “Treason”

Call it, “Love” or call it, “Reason”

But I ain’t marchin’ any more

The Vietnam War (aka The Second Indochina War, aka the War Against the Americans to Save the Nation) began in 1955 and ended when Saigon fell on April 30, 1975. The first US Marines arrived in Da Nang in 1965 but there were already 25,000 American “advisors” there backing up French Colonial forces, the aim being to restrict Communist expansion into Indochina under Stalin and Mao and to battle Hồ Chí Minh, the North Vietnamese Army and the rebel Việt Cộng in South Vietnam and Cambodia. (That’s a great oversimplification but this isn’t a history lesson.) The U.S. would register more than 58,000 deaths during the war; Vietnam would number its dead at 4 million.

When I visited Saigon — now called Ho Chi Minh City — in 2013, 44 years after my Navy pilot shipped out and 38 years after the war ended, my husband and I were on a cruise ship tour of Southeast Asia. I read my book on deck as we sailed northeast from Singapore on the South China Sea.

Though some days were rougher going than others, it was heaven to be on that ship, away from winter in Toronto.

It was late afternoon on February 1st as we sailed up the Saigon River. There were all kinds of fishing boats and sampans but none more interesting than the one below, with its “push-ahead” submerged net attached to the ends of the poles which scoops up small fish while the boat motors slowly ahead. Note the fisherman at the side with the perforated blue laundry basket which has just been lifted from the water, presumably with a haul to be placed in the coolers at the back.

The Saigon River delta on our starboard side consisted mostly of mangrove species, their salt-resistant roots extending into muddy soil at the shore while harbouring molluscs, crustaceans, fish and amphibious species. Migratory shorebirds roosting in the branches and herons could be seen fishing at their base. A few miles behind (but not visible here) is the UNESCO-designated Cần Giờ Biosphere Reserve, a 75,000-hectare mangrove forest and wetland biosystem that has been dubbed the “green lungs” of Ho Chi Minh City.

As we drew nearer to the city, the water became less brackish and we saw nipa palms (Nypa fruticans) interspersed with the mangroves in the slow-moving tidal water. A little further upriver, the mangroves disappeared completely and the nipa palms became the dominant species. Curiously, the palm’s horizontal trunk lies below the soil. The leaves, which can reach 30 feet high, are used for roof thatching and basketry, while the brown flower buds yield a sap that can be tapped to make an alcoholic beverage.

During the Vietnam War, the mangrove-nipa palm forests were used by the Việt Cộng as hiding places and became the target of millions of gallons of Agent Orange defoliant herbicide sprayed from tanker planes by American forces. Despite the fact that Monsanto informed the government as early as 1952 that Agent Orange contained a toxic substance (dioxin), it would be used for almost a decade and cover one-seventh of Vietnam’s land area. In 1969, the UN passed a resolution declaring Agent Orange in violation of the Geneva Convention; the following year its use was suspended. But the damage had already been done, not just to nipa palms and mangroves, but to the Vietnamese and Americans who had come into contact with the deadly spray. Not only would many of them develop lethal cancers, their DNA would suffer damage that, in many cases, resulted in severe birth defects in their children and grandchildren.

From the small village on our port side, below, came a loud, bizarre cacophony of bird-chirping. I overheard something about “birds-nest soup” and later discovered that the tall, concrete building is a commercial birdhouse for edible-nest swiftlets (Aerodramus fuciphagus). The tiny birds, normally cave-nesters, are lured back to their nests on the building’s rafters in the evening by the tape-recorded chirping sound. In other words, the entrepreneur uses the birds’ native “echolocation” trait to call them back to the nest. Turns out those little nests are made almost entirely with bird saliva, no plant material, and they sell for up to $3,000 a kilo. Why? They are the supposedly magical “aphrodisiac” ingredient in the Chinese specialty dish birds-nest soup. Not just a libido pick-me-up, but women also think the gelatinous saliva helps to keep their faces wrinkle-free. Alas, the noise pollution from the big birdhouses has caused problems in areas throughout southeast Asia where governments such as Vietnam’s have offered financial incentives to those wishing to get into the business. I was also intrigued by the two-spired church I saw in this little town, assuming at first it was from the French Indochina period. Except when I returned home and look closely at the shot, I realize those aren’t crosses on the spires — and what church has two spires? It wasn’t until I heard Catherine Karnow give a National Geographic talk on her photography in Vietnam in Toronto three weeks after returning and she described Cao Dai, a religion where people venerate Victor Hugo, Thomas Jefferson and Joan-of-Arc as saints, that I learned what it was I photographed. There’s a lot more to this modern (1926), uniquely Vietnamese religion than that but this was a Cao Dai temple and there are anywhere between 2-6 million adherents in the country.

A barge was tied to the mangroves. Nipa thatch? Nipa alcohol? Shrimp-fishing? Dredging? We had no clue.

The sun had gone down by the time we approached Ho Chi Minh City harbour.

The emerging night skyline was rather shocking to those of us who expected to find a somewhat sleepy Communist version of old French Saigon. But Vietnam is “nominally” Communist and has become the Asian Tiger of the 21st century, with many “boat people” refugees from the 1970s returning to the country to create businesses. However, growth is said to be uneven and bogged down in the old political trappings, corruption, inflation and infrastructure problems.

Good morning, Vietnam! After a night on board dockside, we walked into the city centre the next morning. This was rather orderly traffic for HCMC but it IS a red light, after all. At other intersections, the traffic criss-crosses in four directions in something approaching a random, quasi-choreographed meshing with no one really giving way. And take it from me, it is terrifying to be a pedestrian timidly lifting your foot off the curb to cross at an intersection.

A food vendor was walking by with his baskets and….

… we passed a bicycle loaded with lychees and rambutans.

City gardeners were planting bedding plants on a traffic island in something that looks like spring planting-out at home. But spring, summer, autumn and winter are not words in the southeast Asian lexicon, for Vietnam is governed by monsoons which divide it into two seasons. Early February during our visit is the latter part of the cool northeast monsoon that lasts from October into early April. The hot southwest monsoon – which is the dominant weather pattern in southern Vietnam – then takes over and lasts until September. Though we think of monsoon as torrential rain, the rainy season in south Vietnam is primarily between May and October, with the heaviest rainfall in June.

We passed the Museum of Ho Chi Minh City, taking note of the jet and helicopter on display. Reminders of the war are still very much a presence in this city, which was the American base of operations until 1975.

There was no denying which side won the war. Pictures of Hồ Chí Minh were displayed in many places. Born in 1890, he died in 1969, the year my navy pilot went to Vietnam. He served as Prime Minister of North Vietnam from 1945 to 1955 and was its President from 1945 to 1969. A Marxist-Leninist, he was Chairman and First Secretary of the Workers’ Party of Vietnam. Under his leadership, North Vietnam defeated the French in 1954 and he was a key figure in the People’s Army of Vietnam and the Việt Cộng in the first part of the Vietnam War. In 1976, Saigon was named in his honour. (From Wikipedia)

Built in 1864 by the French, the old Saigon Zoo and Botanical Garden was a welcome green oasis. It was Saturday and lots of families were wandering the paths of the garden. After reunification in 1975, few resources were expended on the garden, but it does contain a good collection of native Vietnamese species and some pleasant areas.

The greenhouse was neat and well-cared for, if not exactly accessible to visitors.

The massive buttress roots of the tung tree (Tetrameles nudiflora), a native southeast Asian species, jutted out into the lawn and cracked the neighbouring sidewalk.

A yellow gibbon nibbled on fruit in its enclosure.

We emerged from the Botanical Garden hungry, yet not quite brave enough to sample the street food from the vendor carts. But just across the street we found a lovely outdoor cafe on the ground floor of the PetroVietnam building. And here I sampled my very favourite meal of the entire trip: Gỏi cuốn, which features ground pork & shrimp with crunchy fresh greens & cilantro in a delectable sauce, all wrapped in rice paper rolls and offered with spicy chili sauce.

My husband ordered a delicious noodle dish. To quench our thirst, we had the most amazing frozen fruit drink. Simple, inexpensive, delicious.

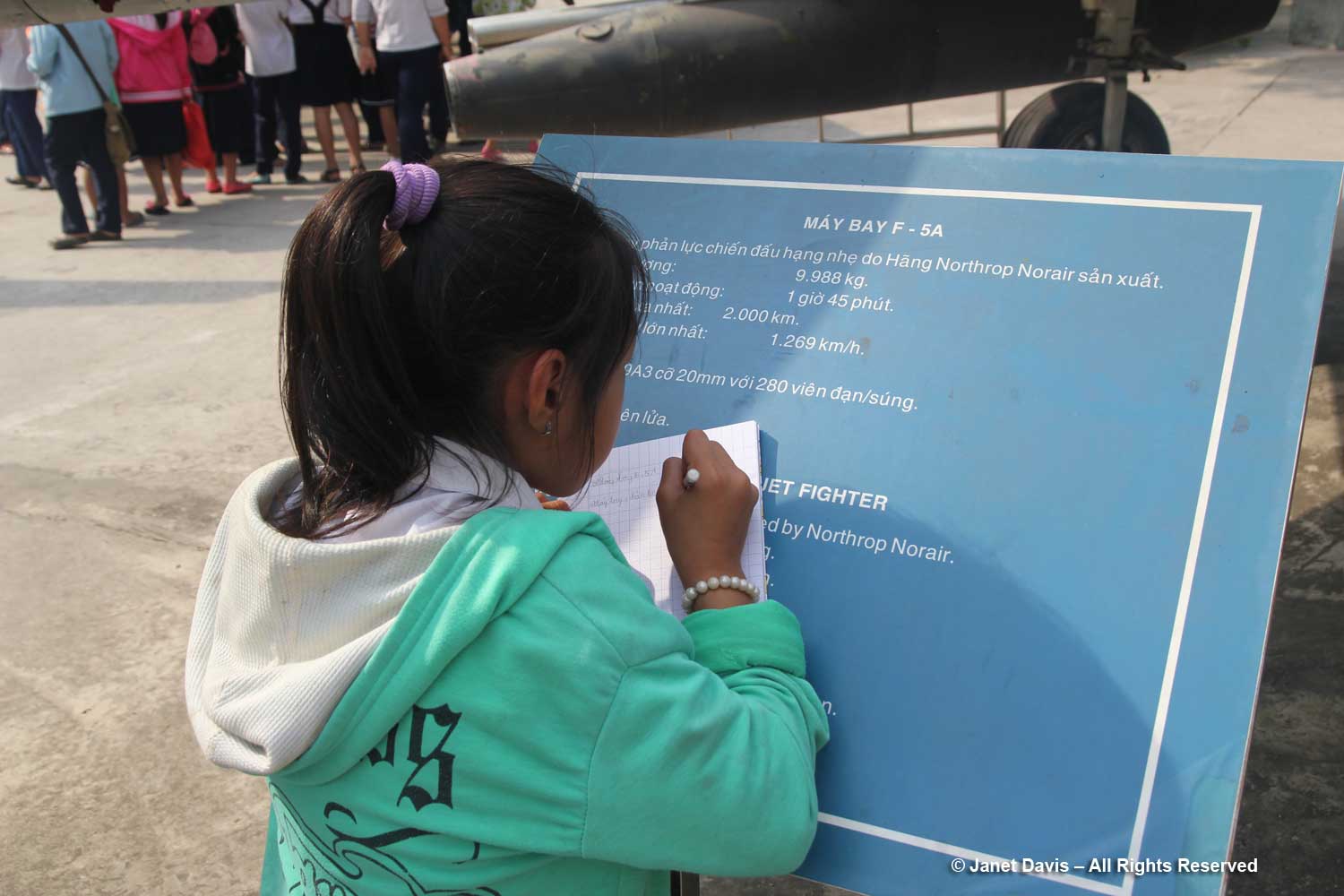

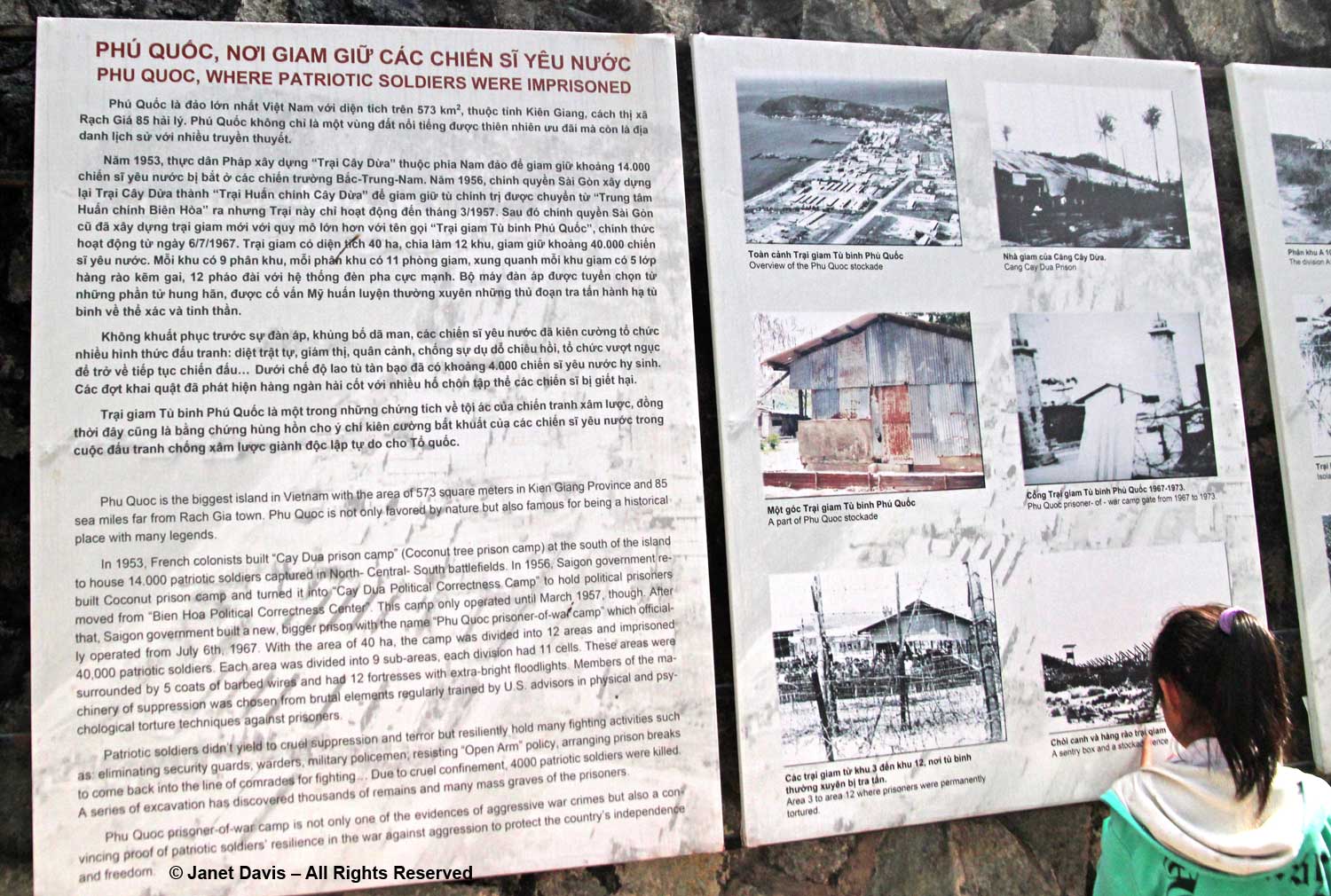

The most evocative stop of our day in Ho Chi Minh City was the War Remnants Museum, or Bảo tàng Chứng tích Chiến. Technically, “the American War” as it is referred to here (never the Vietnam War), began in 1959 with the first battle between the U.S.-backed South Vietnamese army and the Communists; escalated in 1965, when the first U.S. combat troops landed; and ended on April 30, 1975, when the Vietnam People’s Army and the National Liberation Front seized Saigon, raising the North Vietnamese flag over the presidential palace. The involvement of the French in colonial Indochine; the Geneva Accord and the resultant clash of ideologies; Ngô Đình Diệm and the Ho Chi Minh trail; the roles of President Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon; the Viet Cong and Green Berets; the Gulf of Tonkin and the Tet Offensive; the millions of dead and wounded; the protests at home and abroad; Jane Fonda; Apocalypse Now and the Fourth of July: for us in the west, those fifteen years and all the horrific details were the stuff of Walter Cronkite and the evening news. But here in Ho Chi Minh City, renamed to honour the fervent nationalist who refused to accept the separation of his country by foreign states and fought to reunify it, the script is very different, as you might expect. And these school children were undoubtedly learning the story of their country’s war with its “oppressors “and the happy ending that came with its ultimate liberation and reunification. Perhaps inspired by the dove of peace on the facade, they would also be taught to embrace a different way of living in this world — a way to settle differences without resorting to armed conflict. But then wars are not fought by children.

School students gathered around the big Chinook helicopter….

…. and the Cessna A-37 Dragonfly Attack jet.

I saw this little girl taking studious notes all around the museum grounds….

….. even staring at the gruesome guillotine in the outdoor jail exhibit, where the sign reads: “It was brought by the French to Vietnam in the early 20th century and kept for use in the big jail on Lagrandiere Street, now Ly Tu Trong Street. During the US war against Vietnam, the guillotine was transported to all of the provinces in South Vietnam to decapitate the Vietnam patriots. In 1960, the last man who was executed by guillotine was Mr Hoang Le Kha.”

Inside the museum, the Agent Orange room was shocking and distressing, but the living embodiment of the chemical’s effects were the disfigured people selling souvenirs at the museum’s entrance: multigenerational victims of Agent Orange. It is a testament to the healing power of time that many U.S. war vets have returned to Vietnam to work with victims of Agent Orange and the U.S. is also working officially to help clean areas where the toxic spray was used.

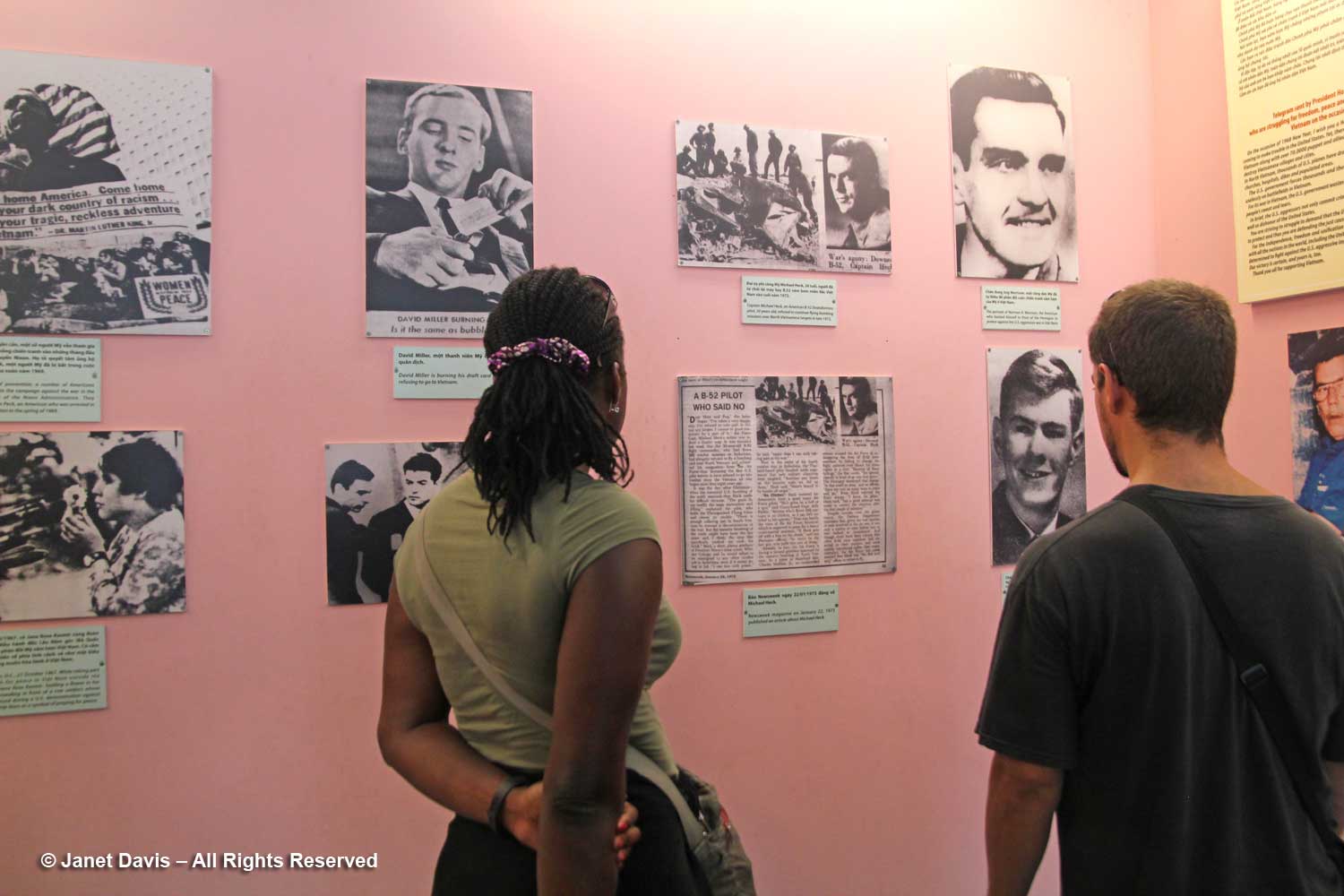

Ample use was made of photos and clippings of American war protestors, conscientious objectors and draft-dodgers…..

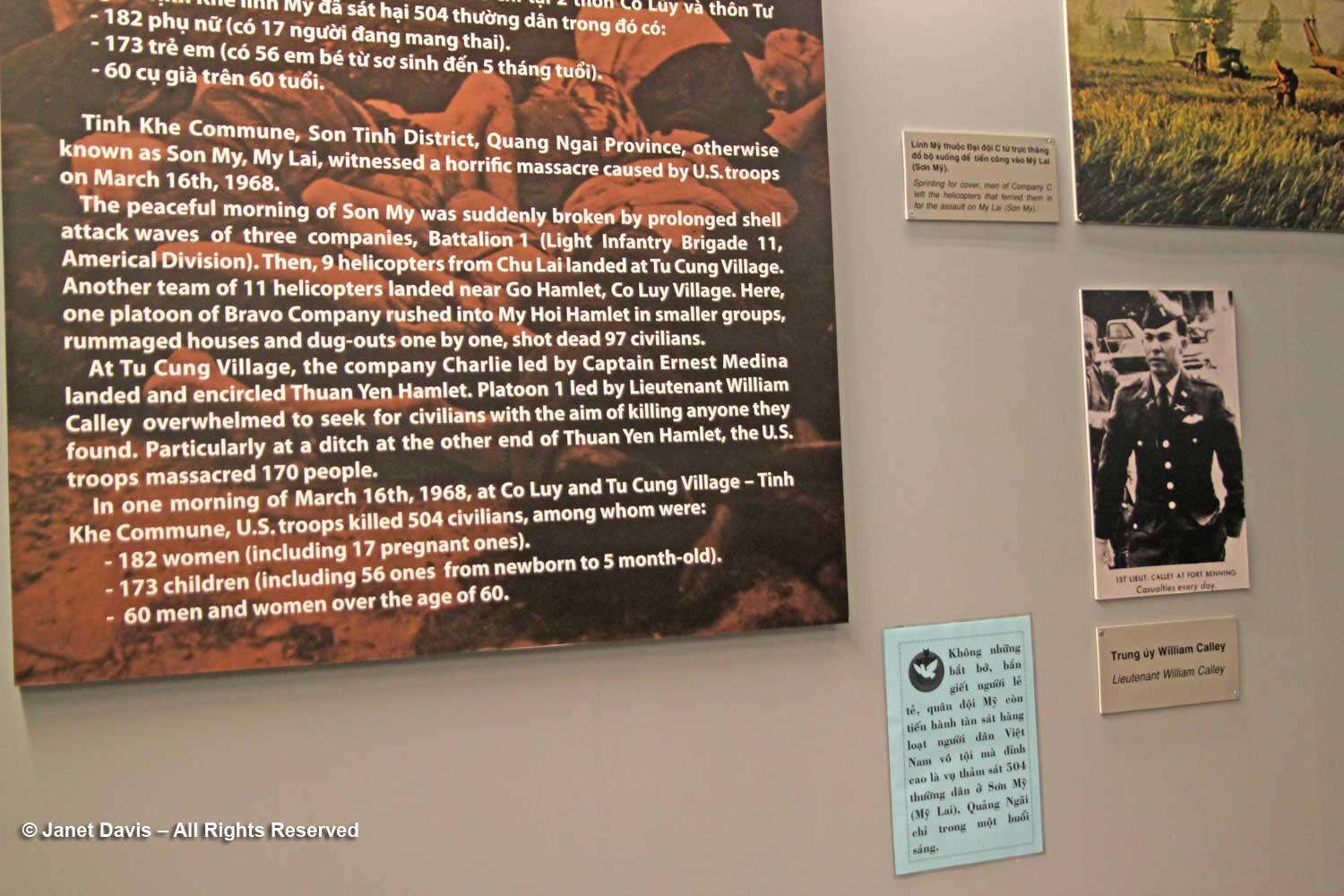

……and atrocities such as that perpetrated in My Lai in 1968 by Army Lieutenant William Calley and his platoon.

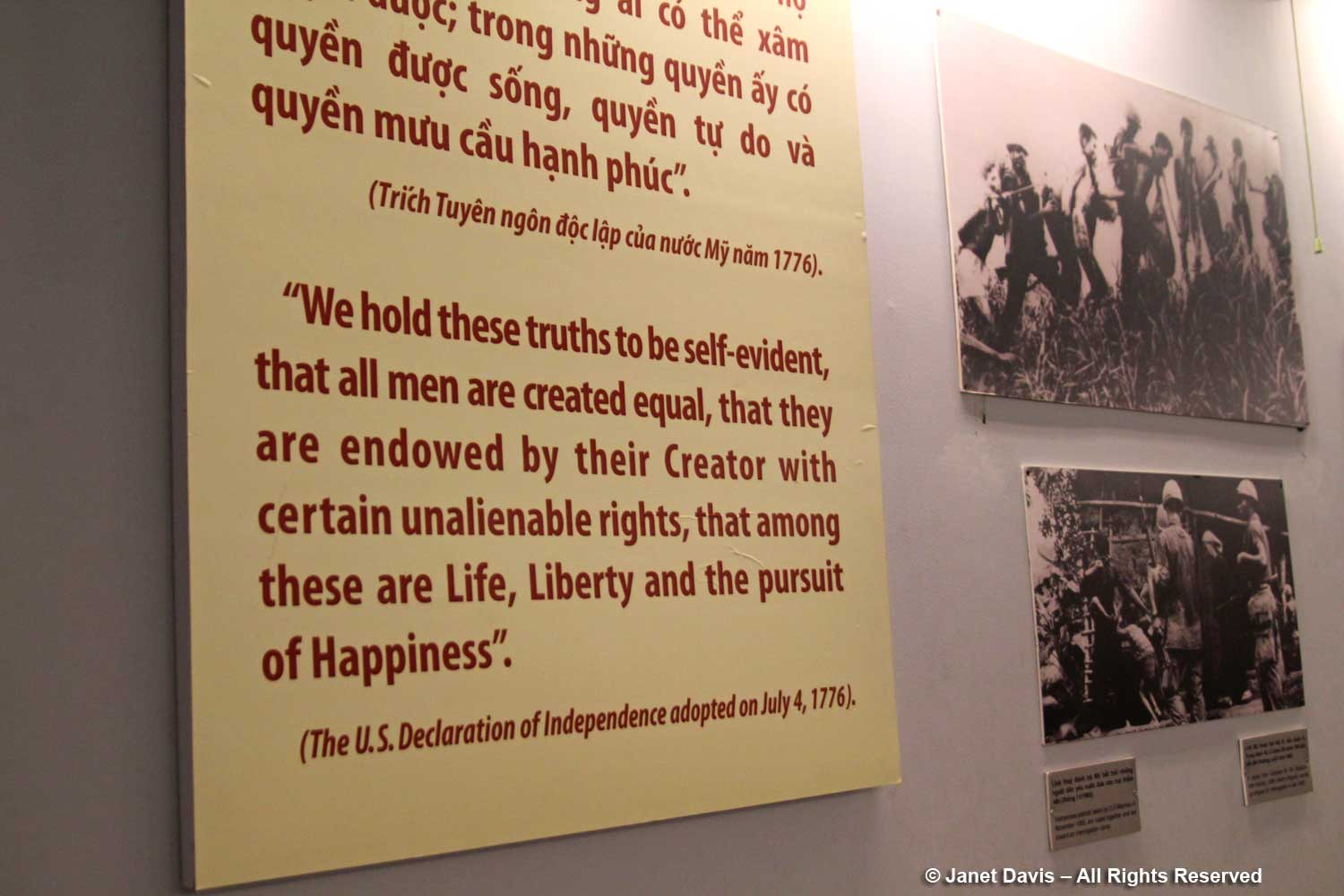

History is written by the victors, it is said, and we were in the land of the victors. Some of the American travellers saw the displays as propaganda and gave parts of the museum a pass. It all depends on your frame of reference, I suppose, but throwing back the U.S. Declaration of Independence at visitors was a masterful touch.

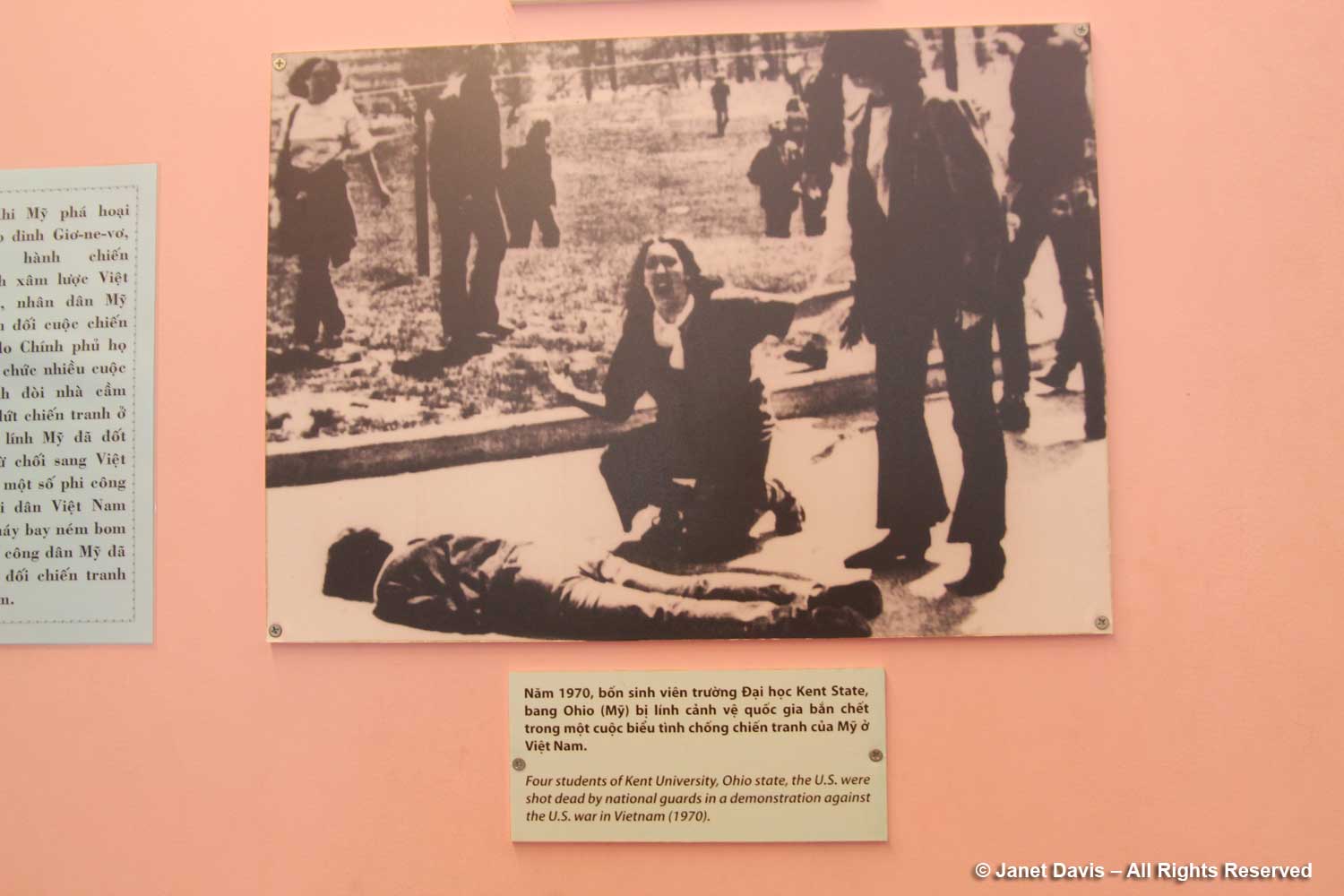

My final image from the War Remnants Museum was a familiar one: the grief-stricken face of a student at Kent State University on May 4, 1970, following the shooting deaths of four fellow students and the wounding of nine by the National Guard during an anti-war protest. That tragic event gave rise to one of the most powerful protest songs of the war, Ohio, written by Neil Young and performed by Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young.

OHIO, Neil Young (1970)

Tin soldiers and Nixon’s coming

We’re finally on our own

This summer I hear the drumming

Four dead in Ohio

Gotta get down to it

Soldiers are gunning us down

Should have been done long ago

What if you knew her and

Found her dead on the ground

How can you run when you know

Ah, la la la la…

Gotta get down to it

Soldiers are gunning us down

Should have been done long ago

What if you knew her and

Found her dead on the ground

How can you run when you know

Tin soldiers and Nixon’s coming

We’re finally on our own

This summer I hear the drumming

Four dead in Ohio

Four dead in Ohio

In 2017, we visited the National Mall in Washington DC. The two-panel, black granite Vietnam Memorial Wall bears the names of 58,320 individuals who died or were missing in action in the Vietnam War.

The names below were among those who died on just two days of the war, June 6th and 7th in 1968, the year that claimed the most casualties. I looked many up on the virtual Wall of Memories; they were Marines or Army, mostly, aged 19, 22, 24. So young…. sons, brothers, lovers. Whatever you think of the morality of war, the wall is a powerful reminder of the ultimate sacrifice made by those who go to battle for their country.

It isn’t possible to know which names on the wall enlisted, and which were drafted. The next song is by the late California singer-songwriter John Stewart (1939-2008) and the video is one I created myself to illustrate the song he recorded that same year, 1968, on the album Signals Through the Glass, along with Buffy Ford, who later became his wife. Some of you might be aware that I spent a few years from 2008 to 2010 working on a theatre treatment of the music of John’s long career, first with the Kingston Trio (1961-67) and later on his own. I wrote a comprehensive blog about that chapter in my life. The song ‘Draft Age’, inspired by a painting by John’s friend Jamie Wyeth, is not strictly a song of protest, but it is an ominous musical preface to the next chapter in the life of young Clarence Mulloy. Balboa in the lyrics is Balboa Park in San Diego. (Eagle eyes will see that I misspelled the fictional lad’s name in the draft letter.) I used public domain Vietnam photos from the U.S. Government to imagine what that might look like.

DRAFT AGE, John Stewart (1968)

Clarence Mulloy stands in his bedroom and stares,

He is going away.

Clarence Mulloy stands at the mirror and shaves,

Today is the day.

Oh, it had to come sooner or later,

That the message of greeting would say,

“Clarence, my boy, you are draft age today”.

Clarence Mulloy looks at his shelves and his soldiers

Made out of clay,

Clarence Mulloy looks at his Ma and they know

There is nothing to say.

Boarding the bus on the corner,

Every face on the street seemed to say,

“Clarence, my boy, you are draft age today.”

And the boys have all gone to Balboa

With some girls that they met on the way

And Alexis stayed home like you told her,

Clarence Mulloy, you are draft age today.

Clarence Mulloy looks out the window and sees

What is passing him by.

Clarence Mulloy how incredibly short it can be

It is making you cry.

And the dirty small boy that has seen you

Looks up from his baseball to say

“Clarence Mulloy, you are draft age today.”

And the boys have all gone to Balboa

With some girls that they met on the way

And Alexis stayed home like you told her.

Clarence Mulloy, you are draft age today.

Clarence Mulloy, you are draft age today.

Clarence Mulloy, you are draft age today.

But this week. The drums of war. Iraq. Iran. Middle East oil. The ancient back and forth. And this century, a changing climate and an increased urgency to enact changes in how we live on the planet before we flood and burn ourselves and the living things around us out of existence. That is, if it’s not already much too late, if we’re not already on ‘the eve of destruction’.

I could have included other songs: Buffy Sainte Marie’s ‘Universal Soldier’, Cat Stevens’ ‘Peace Train’, Bob Dylan’s ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’, Pete Seeger’s ‘Where Have All the Flowers Gone?’, Buffalo Springfield’s ‘For What It’s Worth’. But I think you got my message. And on that note, I’ll finish #mysongscape with Barry McGuire’s raw song of protest. Even with its 1960s references — the space race, JFK’s assassination, the civil rights marches in Alabama, strife in the Middle East and, yes, Vietnam — it seems that we are always poised on the eve of destruction.

EVE OF DESTRUCTION, P.F. Sloan (1965)

The eastern world, it is explodin’,

Violence flarin’, bullets loadin’,

You’re old enough to kill but not for votin’,

You don’t believe in war, but what’s that gun you’re totin’,

And even the Jordan river has bodies floatin’,

But you tell me over and over and over again my friend,

Ah, you don’t believe we’re on the eve of destruction.

Don’t you understand, what I’m trying to say?

And can’t you feel the fears I’m feeling today?

If the button is pushed, there’s no running away,

There’ll be no one to save with the world in a grave,

Take a look around you, boy, it’s bound to scare you, boy,

And you tell me over and over and over again my friend,

Ah, you don’t believe we’re on the eve of destruction.

Yeah, my blood’s so mad, feels like coagulatin’,

I’m sittin’ here, just contemplatin’,

I can’t twist the truth, it knows no regulation,

Handful of Senators don’t pass legislation,

And marches alone can’t bring integration,

When human respect is disintegratin’,

This whole crazy world is just too frustratin’,

And you tell me over and over and over again my friend,

Ah, you don’t believe we’re on the eve of destruction.

Think of all the hate there is in Red China!

Then take a look around to Selma, Alabama!

Ah, you may leave here, for four days in space,

But when your return, it’s the same old place,

The poundin’ of the drums, the pride and disgrace,

You can bury your dead, but don’t leave a trace,

Hate your next door neighbor, but don’t forget to say grace,

And you tell me over and over and over and over again my friend,

You don’t believe we’re on the eve of destruction.

No, no, you don’t believe we’re on the eve of destruction.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qfZVu0alU0I

Music really does bring memories to the forefront. For me “Where Have All the Flowers Gone” brings memories of living at the United States Military Academy, going to summer camp, having tent mates and fellow campers whose fathers were on orders for Vietnam and that was the song they thought would be good for the campers to sing. Still brings a tear to my eye.

“Eve of Destruction” is all too close to reality for today.

Your trip to Vietnam looks to have been quite interesting.

It’s amazing how music so perfectly recalls a time, place and emotion in our lives. Thanks, Jan. I appreciate you coming along on this musical journey.

Too sadly evocative. All the protest songs sing in my memory. If only they had managed to improve the situation in today’s world.

Pat, I so agree. History is written by the victors and no one in power cares about the songs.

A very powerful post. For some reason for me the most moving song associated with the war, though it doesn’t directly mention the war at all, is Who’ll Stop the Rain?, also by CCR. The Vietnam war ended my junior year of high school. I remember passionate arguments with my classmates and going to anti-war protests with my father.

I’ve been watching the Ken Burns documentary series on Vietnam on Netflix. Excellent, but highlights so many tragic mistakes borne of ignorance and arrogance. Interestingly, the documentary says that Ho Chi Minh was reluctant to escalate the war with the Americans, it was his deputy Le Duan who was obsessed with victory at any cost and drove North Vietnamese strategy.

Jason, thank you for commenting. It was such a pivotal time of life for many, this war in a far-away part of the world over far-away political ambitions, with such devastating consequences for young Americans. We watched most of the Ken Burns documentary when it was on PBS originally. Good to know it’s on Netflix.