The day after my rain-soaked visit to the 2024 Chelsea Flower Show (see my recent Show Gardens blog and Great Pavilion blog), it was a pleasure to walk through the entrance door in the brick wall at 66 Royal Hospital Road into the quiet, quaint and decidedly eclectic Chelsea Physic Garden. Occupying 4 acres on the north shore of the River Thames, a stone’s throw from the Flower Show’s grounds in the fashionable Chelsea district, the garden celebrated its 350th anniversary last year, but only opened to the public in 1987, four years after registering as a charity. It is the second-oldest botanic garden in the UK, after Oxford Botanic Garden (1621).

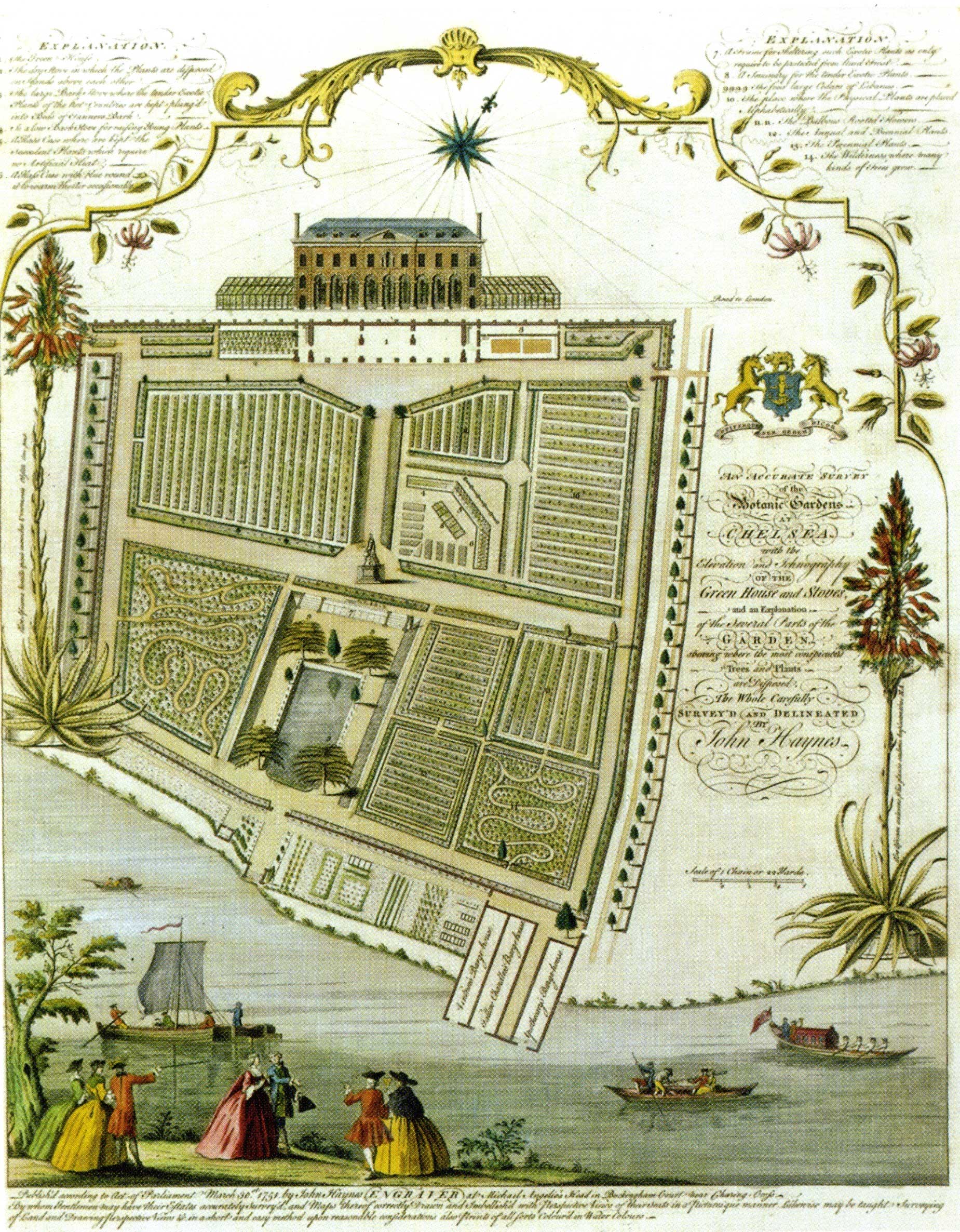

Chelsea Physic Garden started further west on the Thames in 1673 at Sir John Danvers’ estate (adjacent to the 16th century home of Sir Thomas More) as a leased outdoor classroom in which to grow the plants used to train apprentices for the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries, still ongoing today as an association of physicians. When the Danvers house was demolished in 1696, the Society lost its garden. In 1712 Sir Hans Sloane, the Anglo-Irish President of the College of Physicians, collector, botanist and Royal Society president (succeeding Isaac Newton) purchased the 166-acre Manor of Chelsea from William Cheyne; it had once been owned by Henry VIII and occupied by his wives Catherine Parr and later Anne of Cleves, among other famous residents. In 1722, Sloane leased the garden’s 4-acre site to the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries for the sum of £5 per year in perpetuity, plus 50 herbarium specimens to be prepared for the Royal Society, of which he was president. If you had visited in 1753, the map below was your guide, “An Accurate Survey of the Botanic Gardens at Chelsea with the Elevation and Ichnography of the Green House and Stoves, and an Explanation of the Several Parts of the Garden, shewing where the most conspicuous Trees and Plants are Disposed, the Whole Carefully Survey’d and Delineated by John Haynes.” The Thames is shown at the bottom.

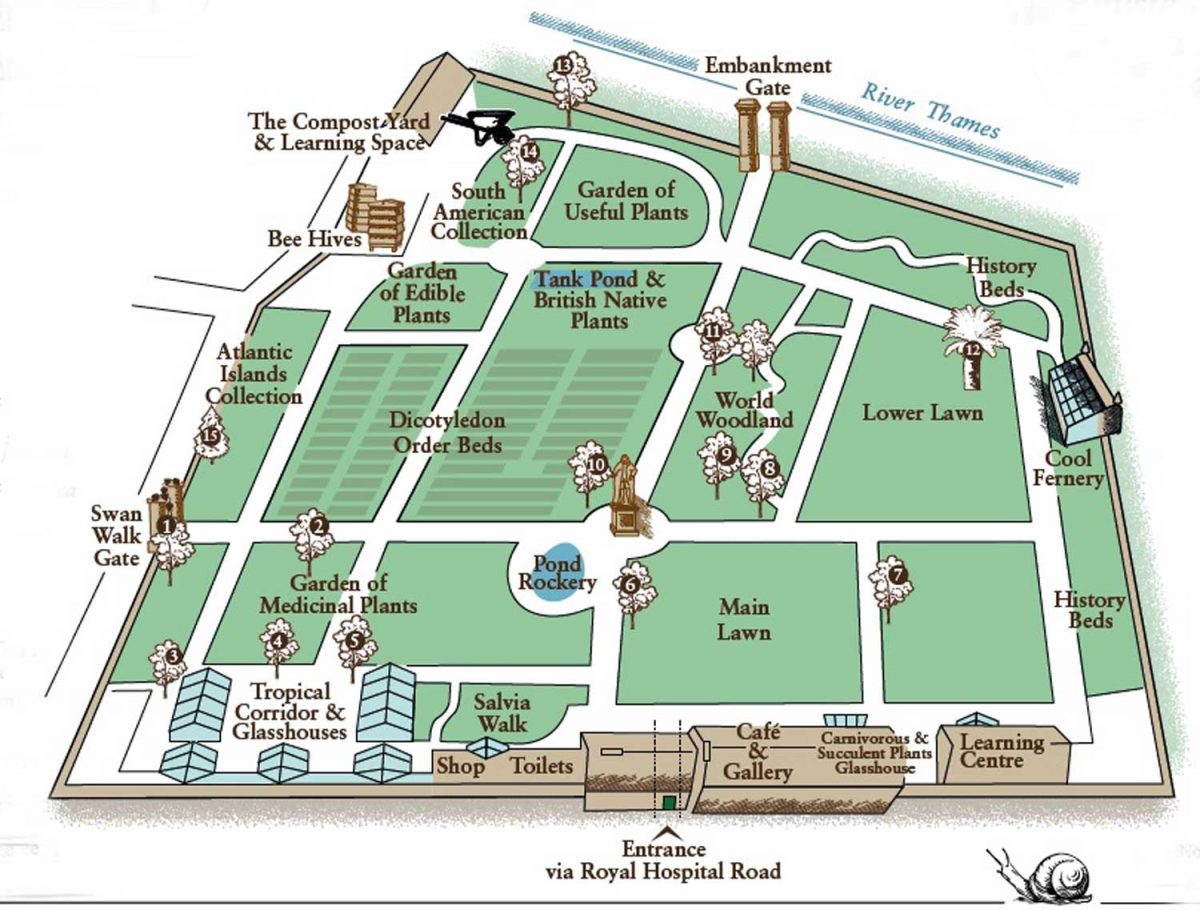

Today’s map is a little more straightforward, but not quite as charming. (See the full .pdf here.) The Thames is shown at the top. Visitors can find some 5,000 taxa of plants, especially edible, useful and medicinal plants from around the world, that help tell the story of humanity’s relationship with plants.

An original statue of Hans Sloane – whose name is also commemorated in Sloane Square, part of the original Chelsea estate – was once in the garden but now stands in the British Museum. I photographed the 2014 Portland stone replacement commissioned by Sloane’s descendant Lord Cadogan on an early spring visit to the garden in 2016. (A few days after my 2024 visit to Chelsea Physic Garden, I would visit the beautiful Cadogan Gallery at London’s Natural History Museum, which became the recipient of much of the collection of Sir Hans Sloane.) As with many public institutions in the 21st century (see my blog on Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello), the garden has acknowledged the history of its original benefactor, which ties in to slavery. “Like many figures of wealth and high social standing, Sloane benefited from the transatlantic slave trade in multiple ways. Enslavement was legal and accepted in England at this time. Sloane wrote detailed accounts of his time in Jamaica. These records show that enslaved Africans and indigenous people provided Sloane with knowledge to advance both his botanical research and understanding of the human body. As a young doctor, Sloane treated enslaved people and his own records show that he did not always treat them with compassion. His wife Elizabeth Langley Rose, inherited sugar plantations in Jamaica which profited from the labour of enslaved people. This provided great wealth for their family.”

I began my visit in the glasshouses near the entrance. The first stove-heated glasshouse was installed at the Garden in 1723 to grow plants from tropical climates, e.g. pineapples. In 1902, a new range of glasshouses fashioned from Burmese teak was installed to house a global collection of plants. In 2022, the glass panes leaking and the wood rotting, they were rebuilt and opened in September 2023 in time for the 350th anniversary. I started in the Pelargonium House, with its collection originally from S. Africa, Australia and Turkey. In 1724, head gardener Philip Miller recorded some 50 species of Geraniaceae plants.

This is Pelargonium caffrum ‘Diana’, a selection of a South African species introduced by Hazel Key in 1990 named for her Wisley Garden botanist friend Diana Miller.

The narrow Tropical Corridor Greenhouse is sited along the garden’s south-facing brick wall and kept above 15C (59F) year-round. It features a collection of important food, medicinal and useful plants from the equatorial regions, including coffee, cocoa, mango and banana plants and orchids.

It also has beautiful specimens of staghorn fern, including this Platycerium superbum.

The Atlantic Islands Glasshouse features many rare plants from the Canary Islands, Madeira and the Azores. It also tells the story of habitats threatened by pests (including humans) and invasive species that compete with native plants for nutrients and space.

This is Aichryson bollei, a suculent endemic to La Palma,Canary Islands.

The Cool Fernery, dating from the 19th century, lies along the west wall and was also recently renovated. It was the passion of Thomas Moore, curator of the Garden from 1848-87. He authored many books on ferns and their allies, including The Ferns of Great Britain and Ireland (1855), helping to popularize ferns in the Victorian era.

The cool, humid Fernery includes aquatic species like floating fern, Salvinia natans.

In the centre of the garden near the Sloane statue is an unusual sculpture-cum-plant support, presumably commissioned for the 350th anniversary engraved with the names of personalities involved with Chelsea Physic Garden from its inception. In the background is a white party tent that was being dismantled – the garden hosts weddings and other functions to bring in revenue.

But the main focus of the garden is plants, including rare plants like Viburnum congestum from China, just beginning to flower.

The Pond Rockery, the oldest manmade rockery in the world, was established in 1773 by botanist and explorer Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820). Like Sloane, he was president of the Royal Society for 41 years, advising King George III on the development of RHS Kew for which he commissioned plant collections world-wide. His own voyages included Newfoundland and Labrador on HMS Niger in 1766; Madeira, Brazil, Tierra del Fuego, Tahiti, Bora Bora, New Zealand, Australia and Java on HMS Endeavour with Daniel Solander under Captain James Cook in 1768-71 (I wrote blogs in 2018 about three gardens on New Zealand’s “Banks Peninsula” named for him); and Iceland on the brig Saint Lawrence in 1772. The plants collected by Banks and Solander on the Endeavor voyage alone led to the description of 110 new genera and 1300 new species, which increased the known flora of the world by 25 per cent. (Wiki) Artifacts from these voyages are displayed at Chelsea Physic Garden, including a pair of clamshells from Tahiti, below.

A bust of Banks nestles in a planting of bigroot geranium (G. macrorrhizum).

The Pond Rockery is intensively planted and surrounds a pond planted with Nymphaea and marginal aquatics. The bronze sculpture by Guy Du Toit is titled Hare and Now II.

Banks included some interesting artifacts in the rockery, including dark volcanic basalt rock brought back as ship ballast from his Iceland voyage and carved masonry pieces from the Tower of London, front left.

Rather than the typical kinds of alpine plants seen in most public rock gardens, the Pond Rockery features plants that thrive in a Mediterranean climate, such as corn poppies and various silver-leaved plants.

Path circling the Pond Rockery.

I had first seen lacy, white Athamanta turbith in Dan Pearson and Huw Morgan’s garden Hillside, which I blogged about in 2023. It is native to northeast Italy, the Balkans and Romania.

Spiny spurge (Euphorbia spinosa) was a new one for me; it’s native to rocky places throughout the Mediterranean.

And I had never come across green lavender (Lavandula viridis) before. It hails from southern Portugal and southwest Spain.

Lovely Tulipa sprengeri from the Pontic coast of Turkey and the last tulip to flower in spring, was keeping company with Digitalis thapsi from the Iberian Peninsula.

Nearby, the Garden of World Medicine with its various themed beds brings visitors to the essence of the Chelsea Physic Garden – many of the plants would be familiar to the Worshipful Apothecaries of the 17th century. In the European bed, we see hops (Humulus lupulus) growing on the obelisk trellis; we know it as a beer ingredient, but it might have been used by the apothecaries as a tea plant for its sedative properties. Other plants in this bed with a history in folk medicine include yellow loosestrife (Lysimachia vulgaris), heal-all (Prunella vulgaris) and chicory (Cichorium intybus).

Asian wild yam (Dioscorea batatas) contains steroidal saponins which a sign in the garden indicates are artificially converted to human steroids for the long-term management of pulmonary fibrosis. That genus name honours the first-century Greek pharmacologist, physician and botanist Dioscorides (c 40-90AD) who authored the first book of medicinal plants, some of which grow in this bed.

Some plants used for medicine are also toxic in the wrong hands, like Digitalis purpurea, common foxglove, below, whose leaves yield the cardiac glycoside digitoxin once used to treat heart failure.

And some are best avoided completely, like hemlock water dropwort (Oenanthe crocata), considered the most poisonous plant in the UK. It likes marshy ground and riverbanks and flowers happily at Chelsea Physic Garden. In fact, Agatha Christie took courses with the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries, and lived quite near the garden in the 1920s and 30s, perhaps doing research for the 14 poisons her characters used in various mystery novels

The Garden of Edible Plants, created in 2012, features a diverse collection of fruits, vegetables and herbs. At one time, a market garden existed on the site so this garden has its genesis in local history, even with its modern connections. Plants in the centre are organized according to their vitamin content while surrounding beds feature a variety of unusual and tender herbs and spices as well as plants used to make edible oils and alcohol. As the garden says, “Did you know that of the more than 20,000 different edible plants on earth, only around 20 are in common production? Find out more about some of the more unusual species in the Garden!”

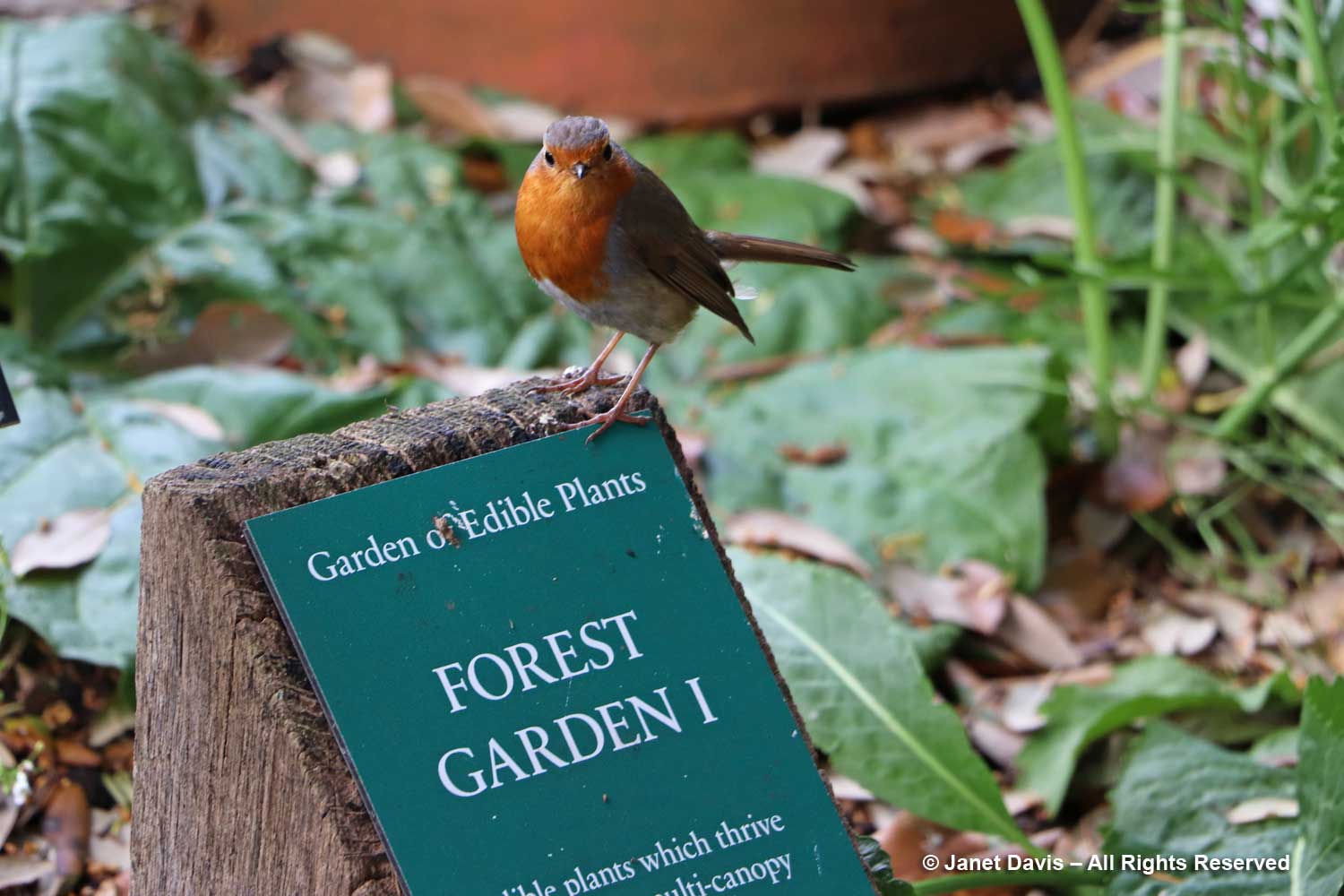

Nearest the Thames and its treed bank is the Edible Forest Garden containing food plants that can thrive “as part of a multi-canopy shaded garden”. Here we see terracotta rhubarb cloches, recalling the year 1817 when a Chelsea Physic Garden horticulturist accidentally dropped a bucket over a rhubarb plant. Weeks later, he lifted the bucket and discovered the plant had responded to the darkness by growing quickly while sending up straight, bright-pink stalks. In time, growers learned that the dark-grown rhubarb was also sweeter and the stalks more tender. The accidental discovery led to an entire Yorkshire UK ‘rhubarb-forcing industry’ using darkened barns and sheds that exists to this day, though not the popular craze it was in the 19th century. (As an aside, I have a gardening friend who travels faithfully each spring to the one Ontario farm that continues this tradition so he can buy tender rhubarb to freeze.)

Each time I’ve visited the Chelsea Physic Garden, I’ve been carefully observed by an English robin. I love these little birds, so much more delicate than our big, raucous American robins.

Nearby, the Garden of Useful Plants features over 200 species used both historically and today, including dye plants, housing materials and bee forage, popular with honey bees from the garden’s hives. In bloom when I visited was the California native lacy phacelia (P. californica), below, which was attracting its share of bumble bees as well. Interestingly, the garden’s longest-serving Head Gardener, Philip Miller, would be the first person to write about bee pollination leading to fertilization and seeds in 1721, the year before he began his 48-year career at Chelsea Physic Garden. Watching bees lighting on tulips in his garden, he wrote: “I saw them come out with their Legs and Belly loaded with Dust and one of them flew into a Tulip I had castrated: Upon which I took my Microscope, and examining the Tulip he flew into, found he had left Dust enough to impregnate the Tulip…. (for they bore good ripe seeds which afterwards grew).” (Flora Unveiled: The Discovery and Denial of Sex in Plants)

I saw bees throughout the garden, including on pink rock-rose (Cistus creticus) in the history beds.

Near the Cool Fernery is the Community Kitchen Garden which hosts a program that brings together people recovering from physical and mental health issues. Here they learn about nature, basic gardening techniques, the healing power of plants and herbal remedies and art.

The Historical Walk in this part of the garden includes a tribute to the Scots-born Quaker Philip Miller (1691-1771), a Pimlico market gardener and nurseryman whom Sir Hans Sloane appointed as Praefectorius (Curator) or Head Gardener, a position he held from 1722 to 1770. In that half-century, he spread the garden’s renown worldwide through his communications and seed exchanges with plant collectors (especially the Philadelphia plant collector John Bartram, who sent the southern Magnolia grandiflora seen in so many English gardens today) and fellow gardeners, including botanists at the Netherland’s University of Leiden and the distinguished 20-member Society of Gardeners, set up in 1725 with Miller as clerk to attempt to eliminate the confusion in plant names. He also authored The Gardener’s and Florists Dictionary or a Complete System of Horticulture (1724), which would have eight editions, and The Gardener’s Dictionary containing the Methods of Cultivating and Improving the Kitchen Fruit and Flower Garden (1731). So perhaps it was no surprise that despite the fact that the 29-year-old Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus made a visit to the garden in 1736, Miller initially refused to accept the young Swede’s binomial system for naming plants, Systema Naturae, first published as a short tract in 1735, published in full in 1753 and ultimately becoming the gold standard for nomenclature. In 1733, Miller sent seeds of the first long-strand cotton developed in the Garden to the new British Colony of Georgia, launching that state’s cotton industry. This big abutilon or flowering maple, below, is Abutilon x milleri – but how and why it was named in his honour is something I’ve not been able to find in my research, or in signage in the garden.

A closeup of the lovely flowers of “Miller’s abutilon”.

The World Woodland Garden – or, as the Garden states “Humanity’s Survival in a Nutshell” – displays 150 taxa of “useful, edible and medicinal forest plants” from three world regions: North America, Europe and East Asia. This is the tall, deciduous shrub common filbert (Corylus maxima), with its edible nuts.

The California native bay laurel or ‘headache tree’, Umbellularia californica grows here too – its widespread use by native North American tribes as a medicinal plant making it an important addition to the woodland garden.

Growing in the shadows here was Chinese mayapple Podophyllum versipelle ‘Spotty Dotty’.

Fortune’s Tank with its aquatic plants and tadpoles was created by the Scots-born plant explorer Robert Fortune (1812-80), who was Curator of the Garden for two years in 1846-48, making many improvements during his short time there. Until, that is, he became “the Great Victorian Tea Thief”, leaving the garden to travel in China, often in Mandarin disguise, to secretly acquire seedlings of Camellia sinensis so Britain could establish its own tea industry in northern India, rather than be dependent on Chinese imports. His 1858 book Journey to the Tea Countries of China made him a household name amongst tea-drinkers.

But it’s the neat, rectangular Dicotyledon Systematic Order Beds that occupy a large swath of the garden where the formal story of botany is told, plant family by plant family, in 800 plants. Laid out in 1902, the beds are organized according to the George Bentham-Joseph Dalton Hooker classification system of 1862-83. This system and more modern systems based on plant characteristics have, of course, been eclipsed by classification based on the DNA and evolutionary trees of plants as formulated by the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG).

In the Lamiaceae or Mint Family bed below, we see lavender, stachys and various sages.

In the Rosaceae bed, appropriately, there are roses, including a David Austin climber and significantly, the native American Virginia rose whose Latin name is Rosa virginiana Mill. That last bit, the author, indicates that this plant was named originally by Philip Miller in 1768; it also appears in the 8th and final folio edition of his Gardener’s Dictionary (1768) as “the Virginia rose”. As a former nurseryman, Miller was very familiar with and seemingly fond of all the species and hybrid roses available in London in the mid-18th century.

In the Caryophyllaceae bed were clove-scented pinks or Dianthus species of several kinds, (though I think a few of the labels were incorrect.)

Circling around to the northeast corner of the garden and the South American section, I walked past the cinnamon-hued trunk of the Chilean myrtle tree (Luma apiculata).

And I came upon a pretty, little Chilean sub-shrub called violet teacup flower (Jovellana violacea).

Given all the historic and rare plants at Chelsea Physic Garden, the plant sighting I treasured most, as a long-time garden writer and photographer, was an unassuming little thing that most visitors would miss completely. I would have missed it too, had I not come upon a tour being given by the Chelsea’s former head gardener Nell Jones in which she was pointing to a small weedy plant in a sunken terracotta pot. In many ways tiny thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana), a cosmopolitan member of the Brassicaceae family, is the most famous plant on earth given that on December 13, 2000 – a four year effort by the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (AGI) consisting of scientists from the U.S., Europe and Japan culminated in the full sequencing of its genome – the first time any plant’s full DNA had been sequenced. As the press release said on that day: “For the once-humble Arabidopsis, simplicity is truly a virtue. Its entire genome consists of a relatively small set of genes that dictate when the weed will bud, bloom, sleep or seed. Those functional genes have their counterparts in plants with much larger genomes, such as wheat, corn, rice, cotton and soybean. Unlike the human genome, Arabidopsis has few ‘junk’ DNA sequences that contain no genes. The plant is practical for scientists because it matures quickly, is small and reproduces abundantly. All these physical and genetic traits add up to an especially useful organism whose genome is now catalogued for the public’s benefit. ‘The Arabidopsis genome is entirely in the public domain, so the research results being announced today are immediately available to scientists across the world,’ said Daphne Preuss, an advisor to the AGI and a faculty member in the University of Chicago’s Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology. ‘Because its implications for farming, nutrition and medicine are potentially vast, this plant has gradually become quite indispensable to us’.”

I looked longingly at the Plant Sale stand but as a Canadian, it was just window-shopping for me.

However, the Chelsea Physic Garden gave me a serendipitous gift in that I was able to have a brief, lovely meeting there with the English Facebook friend I met online long ago. Along with a group of nurserymen and plant geeks, Alan Elsbury started the Plant Idents Facebook page 14 years ago and, for my sins, I became one of the administrators of the page with its 7,700 members more than a decade ago. He was on his way to the Chelsea Flower Show and we had a fun chat.

I finished my visit with a lovely lunch of smoked salmon & salad in the Physic Garden Café and, honouring that long ago gardener who accidentally discovered rhubarb-forcing at the Chelsea Physic Garden, a glass of Cawston Press Sparkling Rhubarb & Apple Juice. The perfect end to a perfect visit.

*****

The Chelsea Physic Garden is open from 11 am to 4 pm every day except Saturday, when it is closed.

what a wonderful post! i visited the chelsea physic garden some time in the 90’s before i was totally obsessed with gardening. my friends who were with me had a surprisingly fabulous time and i was the hero of the rest of the trip because i had come up with the most unusual place that was the most fun! that afternoon is also memorable because we all had our first mojitos in a bar on our way back to the tube. thank you for the memories, and for all the wonderful information

Thanks, Lisa. Mojitos after the Chelsea Physic! The garden would approve of all that Lamiaceae mint and sugarcane rum! It is an unusual place, but I still didn’t see it all.

Would love a second visit there. And I covet. A pelargonium called Diana!

Diana, thank you. And I agree – given your knowledge of S. African species, I think a cultivar of P. caffrum called ‘Diana’ is perfect for you.

As always, thanks for the great tour and the information on the history and the amazing landscaping and plants. The pots in the photo with the statue really caught my eye–the conifers with trailing vines and purple flowers…elegant and lovely.

Thanks, Beth! Yes, I didn’t manage to get to all the nooks and crannies, but most of them. So much to see.

Thanks yet again Janet for letting me tag along. So much to learn so little time. xox

My great pleasure Donna. You’re right, so much to learn. And then re-learn as if you’ve never heard of it before!