It was a showery May 26th morning as we crossed the Tower Bridge over the Thames while watching for the first competitors in the LondonRide bicycle race to charge across the finish line just beyond. The bridge opened on June 30, 1910 after sixteen years of construction — 800 years newer than the crenellated White Tower, seen through the bridge’s struts at left, which was built by William the Conqueror in 1078 and finished after his death around 1100. The oldest castle in England, it sits behind battlements at the centre of the Tower of London Fortress, along with the Waterloo Barracks containing the Crown Jewels and the old Mint. But we were crossing the bridge to visit the moat encircling the Tower and its spectacular show of wildflowers.

On the embankment of the Thames in front of the Tower, interpretive signage greets visitors, highlighting moments in English history. This portrait of Elizabeth I (1533-1603) is a reminder that royalty has always been a point of intrigue in Great Britain, though much more dramatic than in modern times. The daughter of Henry VIII and his second wife Anne Boleyn, she was just 2 years old when her mother was beheaded by the king, the first execution of a queen of England. She would assume the throne after the 1558 death of her half-sister, Mary Queen of Scots, daughter of Henry VIII’s first wife Catherine of Aragon, and rule England and Ireland for 44 years as “Good Queen Bess”.

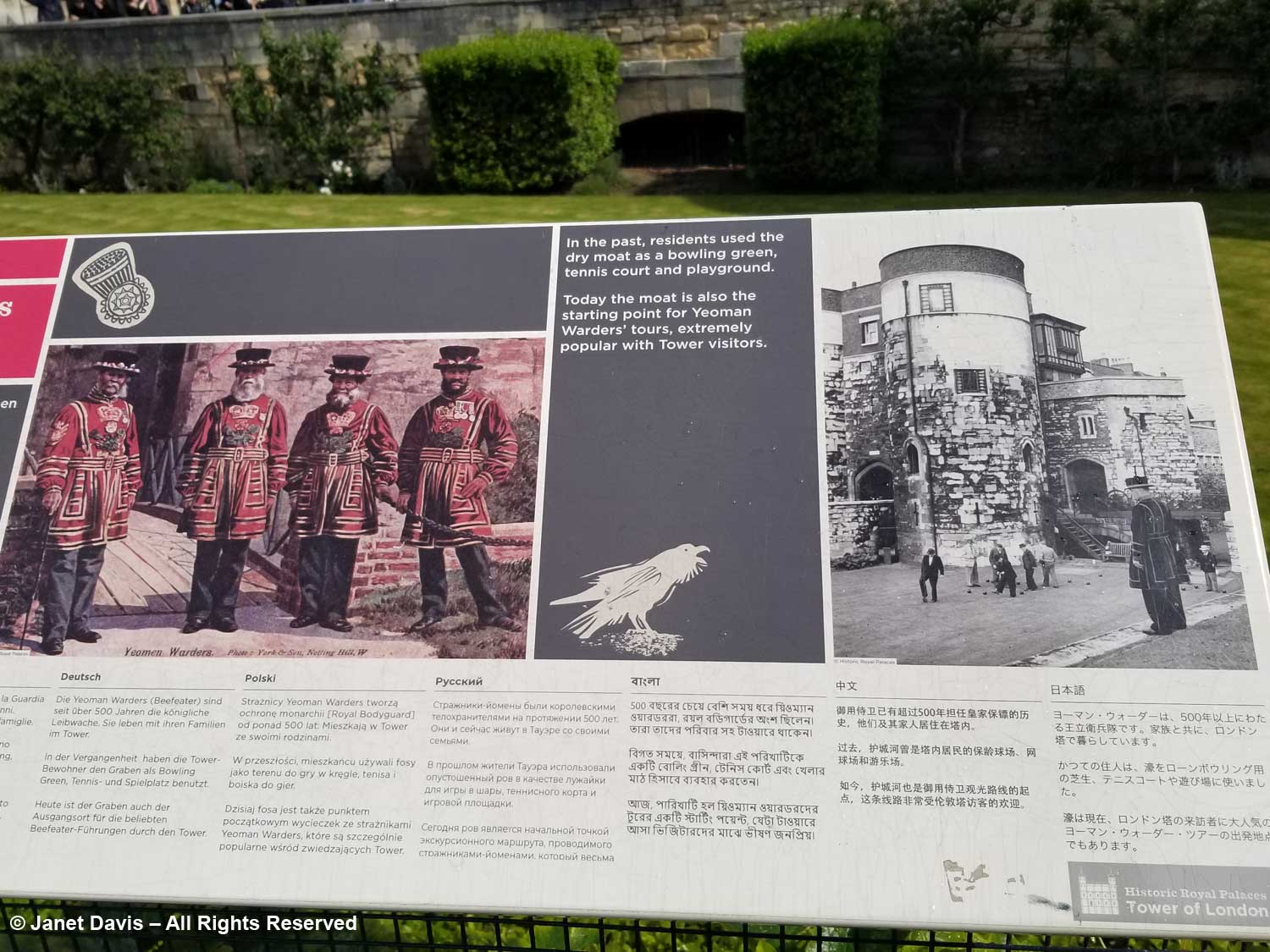

The Yeoman Warders – the “Beefeaters” – who guard the Tower and have apartments within the complex are also featured on signage.

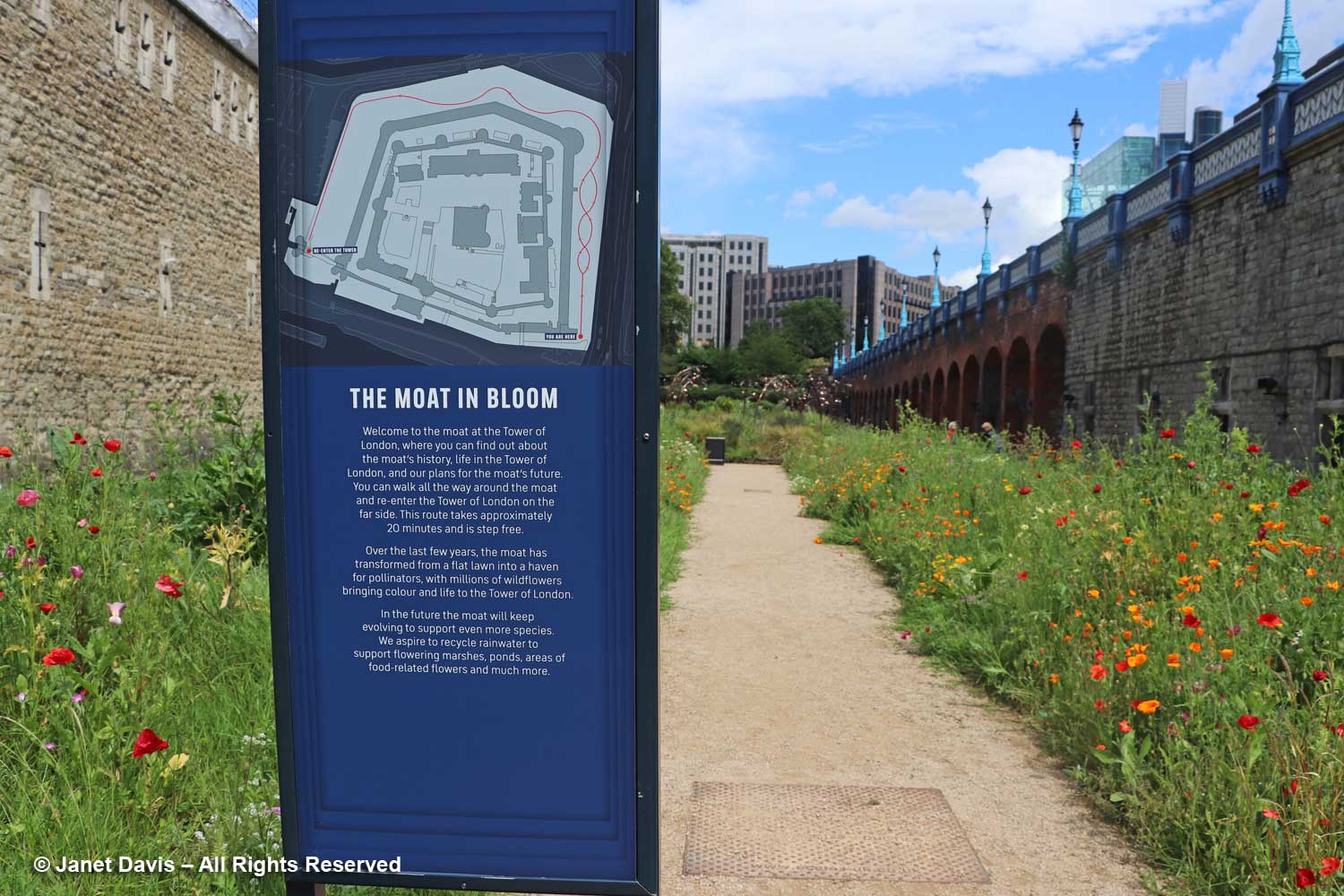

The closely-shorn lawn at the Tower’s southwest corner near Byward Tower is part of the original dry moat, but a much tamer version of the wildflower moat beyond. As the sign in the photo above said, it was once used as a bowling green by the Tower’s residents; its sunny aspect mean it was also used for growing vegetables. Note the cross-shaped “arrow slits” in the fortification walls.

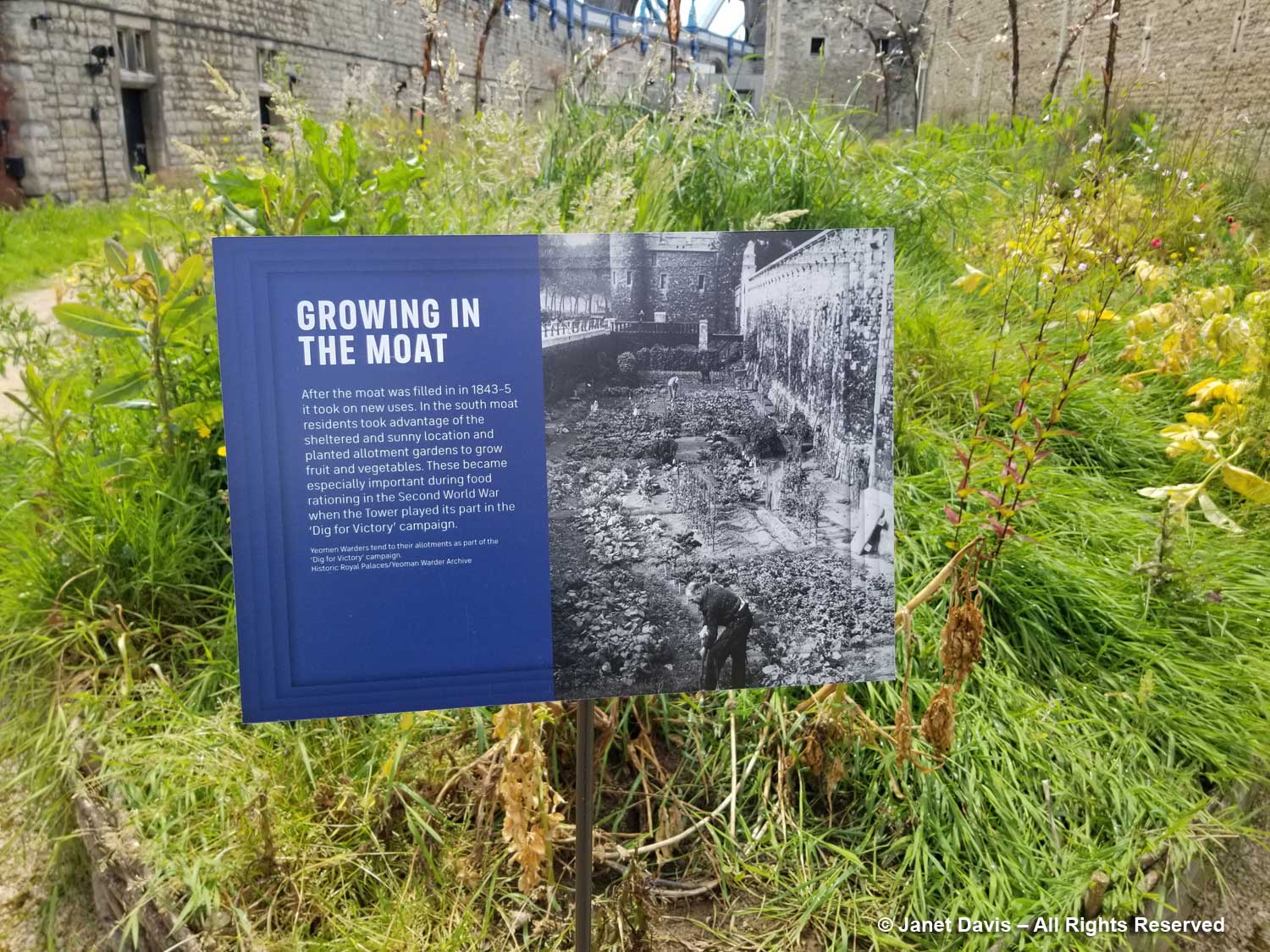

The moat wasn’t always dry, of course. It was fed by the River Thames, below, and extended in 1285 by King Edward I to keep potential attackers at a distance. Fifty metres (164 feet) wide in places and very deep at high tide, it was also stocked with pike to be farmed for the fortress residents. In fact, wicker fish traps from the 15th or 16th century were found by archaeologists, complete with fish skeletons. But around 1843, a deadly, water-borne infection struck, believed to be caused by the “putrid animal and excrementitious matter” of the moat at low tide. So the Duke of Wellington ordered the moat drained and turned into a defensive dry ditch or “fosse”. Dry it would remain until January 7, 1928 when heavy rain caused the Thames to overflow its banks and flood the moat, allowing photographers to briefly capture how it looked when filled with water. During the Second World War, it was used as an allotment Victory Garden for the residents. By the way, that pointed skyscraper on the south side of the Thames is The Shard, the tallest building in the UK at 1,016 feet (309 m).

We watched as a Yeoman Guard began his guided tour of the Tower in the wildflowers of the moat. Unlike those tourists who headed inside the walls, I was content to spend my entire visit in the flowers.

The 2024 version of the “Moat in Bloom” I saw was two years after the Superbloom of 2022, part of the 4-month-long Platinum Jubilee celebrating the 70-year reign of the late Queen Elizabeth II, who acceded to the throne on February 6, 1952 upon the death of her father, King George VI. Here we see the artistry of both landscape architect Andrew Grant of Grant Associates and planting designer Nigel Dunnett, Professor of Planting Design and Urban Horticulture at the University of Sheffield and founder of the seed firm Pictorial Meadows in 2003, who collaborated under Historic Royal Palaces (HRP) to transform the moat into what Grant called “a joyous shout out for change; a marker in how we can move forward in the way we think about and manage our heritage for the benefit of future generations“. In the photo below taken from the public area near the ticket entrance above the moat, we see how Grant designed the willow-edged cutouts in the moat to mirror the arched windows in Mount Legge, the northwest tower in the outer fortification wall (all the towers have names and histories). We also see the descendants of the 20-million wildflower seeds of 48 species and 16 seed mixes sown originally for Superbloom.

Long before Superbloom, Nigel Dunnett had established his reputation with the 2012 planting at the London Olympic Park; the Buckingham Palace Diamond Garden for the 60th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth’s accession to the throne; a 2013 redesign of The Barbican complex in London with drought-tolerant, perennial steppe species; a Gold-Medal-winning rooftop design for the 2013 Chelsea Flower Show; and his stunning ‘Grey to Green’ landscape work with the industrial city of Sheffield beginning in 2014 and continuing today, and many other projects to beautify the public realm. As for the moat, the scene below could be an Impressionist painter’s canvas! In fact, Nigel Dunnett was inspired by pointillism, especially the work of artist Georges Seurat, as he wrote on the original Superbloom design process in his Instagram account. “These brilliant and analytical explorations of colour relationships… were pivotal in the design development of the seed mixes and their spatial arrangement. The precise selection of individual colours, their proportions, densities and distributions give rise to the larger scale impression. It’s just a small leap to make the connection to meadows and naturalistic planting.” To accomplish this with technology, Dunnett used pixel diagrams as abstractions to create the colour balance and mix proportions with flower seeds.

Then it was time to take the curving path through this magical moat meadow, its exuberance held at bay by low willow wattle fencing produced by Wonderwood Willow in Cambridgeshire. Wrote Nigel Dunnett: “The 2022 Superbloom was a catalyst, a tipping point for this permanent transition of the moat, which must be Central London’s largest and most prominent ‘wilding’ project. It was great to see people down in the moat as part of the everyday visitor experience to the Tower – before 2022 these were inaccessible monotonous mown lawns.”

In certain places, perennials such as yellow-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium striatum), lambs’ ears (Stachys byzantina) and magenta Knautia macedonica flower alongside the annuals.

The white form of biennial rose campion (Lychnis coronaria ‘Alba‘) added its silvery foliage while lilac Scabiosa columbaria was attracting loads of bumble bees.

This is Bombus terrestris, the common buff-tailed bumble bee sharing a scabious bloom with a hover fly.

A number of benches are placed at intervals throughout the moat.

My three menfolk, husband Douglas, London-based son Doug and his partner Tommy were blown away by the beauty of the moat in bloom. And of course we needed a selfie!

Readers who know my interest – and the name of this blog – know I love to focus on colour. But meadows are also a great passion with me, tracing back to my childhood on Canada’s mild west coast. I talked about this at the beginning of my 2017 two-part blog on Piet Oudolf’s design for the entry garden at the Toronto Botanical Garden: “Piet Oudolf: Meadow Maker“. More than anything else, this is my favourite style of garden, its wildness as vital as its colour associations. Nigel Dunnett also felt this attraction as a child: “From as long as I can remember, I have been inspired by the wild; by the experience of nature. It’s an emotional response. Some of my earliest memories are of being in beautiful flowering meadows, or woodlands in the spring full of wildflowers, and it’s these more intimate or human-scale associations that perhaps made a stronger impression than big dramatic wide landscapes and scenery. That emotional response was, and is, strongly positive: provoking hugely uplifting and joyful feelings.” Below we see various colours of California poppy (Eschscholzia californica) along with blue cornflowers (Centaurea cyanus).

I was fortunate to be in the moat when the poppies and cornflowers, below, were at their very best.

Here we see annual yellow corn marigolds (Glebionis segetum formerly Chrysanthemum) with the California poppies and cornflowers.

We were all competing to see who could get the best photo of…..

…. bumble bees on pollen-rich corn poppies (Papaver rhoeas).

Mauve and white corncockle (Agrostemma githago) is one of my favourite annuals. In fact, I grew it from seed in a big pot this year, along with corn poppies.

In places, the path was marked by drilled bamboo posts threaded through with rope.

A profusion of scentless Mayweed or chamomile (Matricaria inodora) along with oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare) created drifts of starry white throughout the moat. White bishop’s flower (Ammi majus) had not yet started to bloom here, but I saw that beautiful umbel as the star of another Pictorial Meadows seed mix garden at the Royal Botanical Garden Edinburgh in late August 2022, next photo.

I think this meadow was my favourite part of our visit to RBG Edinburgh. It is the Classic mix in the Pictorial Meadows brochure.

Back to the moat. Circling the northwest Mount Legge fortification tower built in the 13th century, it’s interesting to contrast it with The Shard, built eight centuries later. The blue flowers at right are blue thimble-flower (Gilia capitata). In the original Superbloom seed mix, Nigel Dunnett used washes of blue flowers to recall the water of the original moat fed by the River Thames.

Here is another view of this combination.

Is it possible I love Gilia capitata?

A little further down this path, some grasses have made their presence felt, creating a softening of the wildflower scene. Although most of the original Superbloom annuals have reseeded in the subsequent two years, additional reseeding and top-ups are now managed by the Tower of London garden team.

Gilia capitata from California is very attractive to the European buff-tailed bumble bee, Bombus terrestris. For me, this is yet more evidence of a scenario I’ve found in my photographic journey over the past three decades: bees need protein and carbohydrates, they don’t check the native provenance of plants when they’re foraging for food. Protein is protein; sugar is sugar. Obviously, a large population of native plants will appeal to the pollinators that co-evolved in the ecosystem. But if the ecosystem is degraded, i.e. if urban development has scattered native plant communities, bees will secure food from whatever plants are available.

Historic Royal Palaces is keen on messaging about pollinators in the moat. This year’s flowering is still the “ghost of Superbloom”, but as Nigel Dunnett notes the plan is “for the final transformation into a biodiverse habitat landscape based on native plant communities to happen in 2025.”

Oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare) attracts short-tongued pollinators, including various types of hoverflies.

I was delighted to see plantain (Plantago major) in the moat, because even as an invasive weed at the edge of my meadows in Canada, it attracts lots of bees seeking pollen.

Corn poppies (Papaver rhoeas) are a mainstay in the moat – as they are in fields of Europe, and as they were in the battlefields in John McCrae’s famous World War One poem. “In Flanders fields, the poppies blow/Between the crosses, row on row,/That mark our place.“

Though the initial soil for Superbloom was engineered for the site and free of weed seeds, two years on the odd adventitious weed species has found a home here, like the yellow sow-thistle (Sonchus arvensis), which was also attracting its share of pollinators.

Corncockle (Agrostemma githago) and corn poppies (Papaver rhoeas) make fine companions.

Biennial blackeyed susan (Rudbeckia hirta ‘My Joy’) was just coming into bloom.

Here and there, violet larkspur (Consolida ajacis) towered over the wildflower tapestry.

Though they have no nectar, poppies offer abundant pollen, like this California poppy (Eschscholzia californica) feeding a marmalade hoverfly (Episyrphus balteatus).

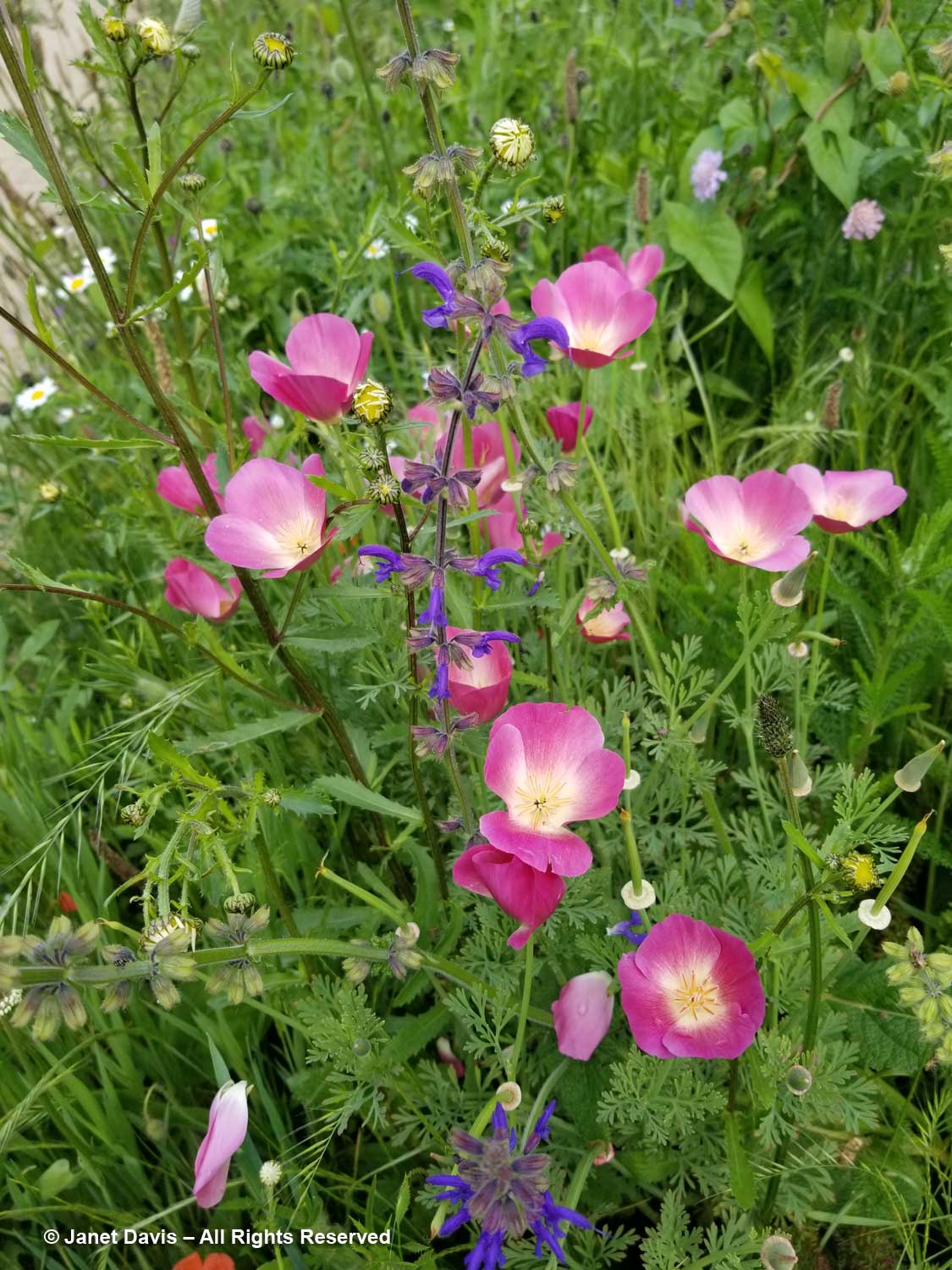

Shirley poppies are a special seed strain of corn poppy, Papaver rhoeas featuring different colours, like white, pink (below), lilac and bicolour, some with semi-double petals and no black blotch near the stamens. They were selected originally by Reverent William Wilks, vicar of the parish of Shirley, England, who spent several years beginning in 1880 hybridizing the wild poppies in the fields near his garden to obtain the strain of poppies bearing his name.

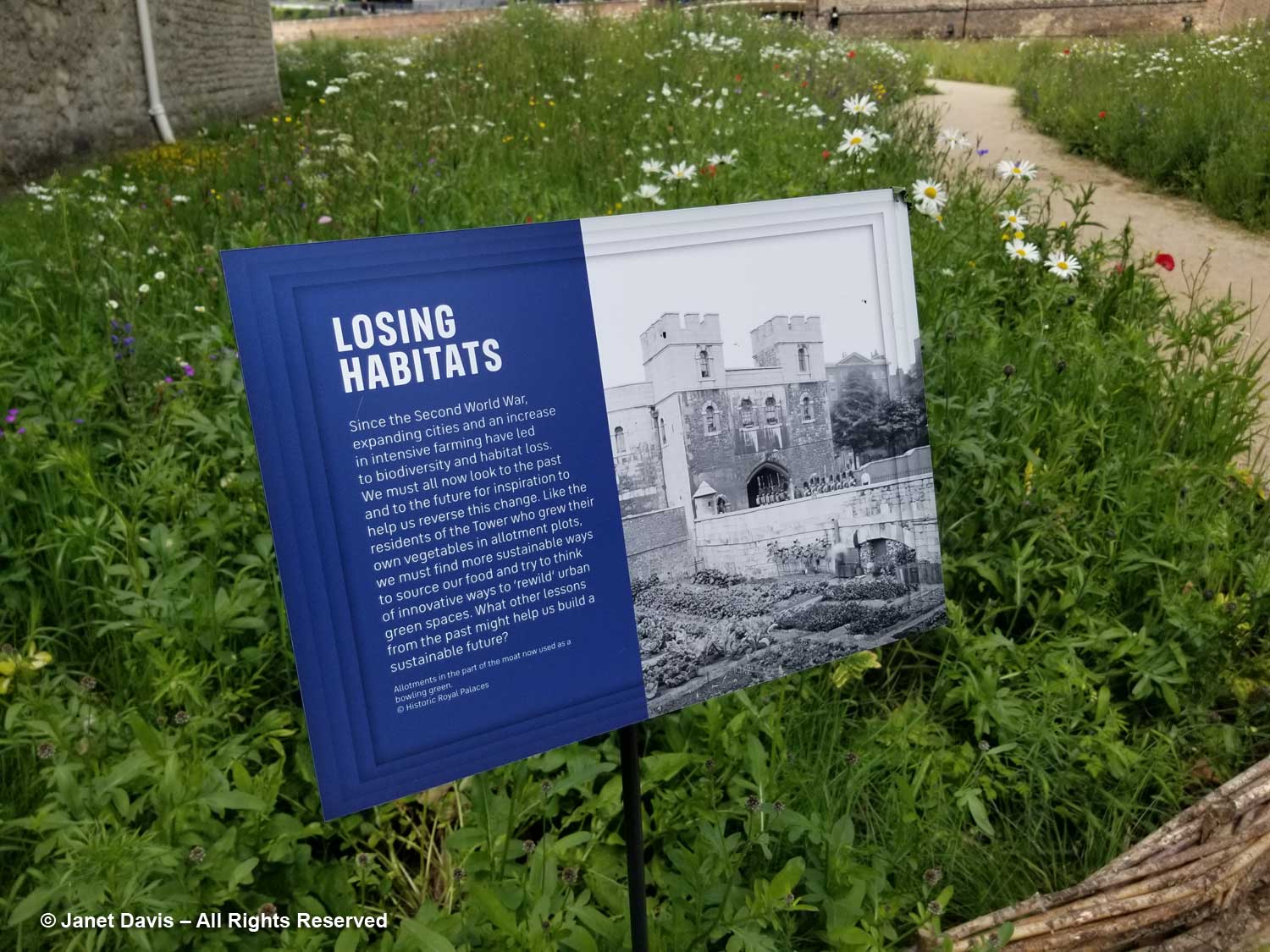

Interpretative signage keeps visitors informed of Historic Royal Palaces’ plan for the moat.

Small scabious (Scabiosa columbaria) is a big draw for pollinators.

The buff-tailed bumble bee (Bombus terrestris) is Europe’s most common bumble bee.

Meadow sage (Salvia pratensis) is a clump-forming perennial that prefers well-drained soil in full sun.

Nigel Dunnett specified the biennial viper’s bugloss, Echium vulgare – another bee favourite. Here it grows with corncockle (Agrostemma githago).

The Tower of London is famous for its six raven guardians, an institution believed to have started with Charles II who insisted the birds be protected and thought the crown and Tower would fall if they flew away. But this magpie does not have any official duties and has staked out its own priority seating in the north moat.

Look at the lovely flower of corncockle (Agrostemma githago), so pretty despite being very poisonous. In the 19th century it was a common annual weed of roadsides, railway lines and wheat fields and it likely made its way throughout the world as part of exported European wheat.

Although cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris) was mostly finished in England when we were there in late May, a few plants popped up in the moat, right.

Annual corn flower (Centaurea cyanus) also comes in mixes that contain blue, white, pink and purple flowers – all are foraged by bees.

When I was at the Chelsea Physic Garden the day before visiting the Tower of London (here’s my blog), they had used annual lacy phacelia or purple tansy (Phacelia tanacetifolia), below, in a mass planting as bee forage for their hives. Despite being a native of California, it is a strong polllinator lure.

Here a buff-tailed bumble-bee enjoys foraging on the unusual caterpillar-like inflorescences of Phacelia tanacetifolia.

Signage helps visitors understand the possibilities of the moat, beyond its origin as fortification.

A lovely combination of pink California poppy (Eschscholzia californica) and meadow sage (Salvia pratensis).

Marmalade hoverfly (Episyrphus balteatus) on pink California poppy.

The north side of the moat offers a good view of the 20 Fenchurch Building, nicknamed the “Walkie-Talkie” for its shape. This is the building which, as it was under construction in 2013, reflected the sun in such a way as to melt the metal of a Jaguar car parked beneath it, forcing the developers to erect a permanent sunshade of horizontal aluminum fins. The north part of the Tower complex behind the battlements is the site of the Waterloo Block and the Jewel House containing the well-protected Crown Jewels. For Superbloom, the north moat was fitted with speakers to create a sensory experience beyond the floral show. Musician Erland Cooper was commissioned to create a soundtrack, which he called “Music for Growing Flowers”.

Along with the corn poppies and California poppies, the moat seed mix contained seeds of Viscaria oculata, the small, lilac-purple flowers at bottom right.

Some plants I photographed don’t appear on the original seed lists but were happily luring insects, like what I believe is a yellow sow-thistle (Sonchus spp.) below. The purple cranesbill in the background is Geranium pyrenaicus.

Circling around to the eastern moat, at the corner we pass through The Nest, an organic willow sculpture by Spencer Jenkins that frames the view of the Tower Bridge.

Yellow buttercups (Ranunculus acris) and purple knapweed (Centaurea nigra) can be seen in the wildflower mix here.

The hardworking willow wattle fencing – nearly one kilometre in length by Wonderwood Willow – keeps the meadow from subsuming the grit path here. According to Andrew Grant in an article in Landscape: The Journal of the Landscape Institute: “We were after a palette that would complement the stonework: colours, textures and form found around the Tower, yet were low in energy in terms of construction, were low carbon and (where possible) were from a renewable resource. As a principle, the use of concrete was banned across the project.”

Wrote Nigel Dunnett of the east moat: “Here the Grant Associates masterplan introduced areas that were more intimate and playful, with smaller paths bringing people into more intimate contact with the flowers. The use of natural materials and the rustic forms of the woven willow structures created a wonderful foil for the flowers.”

On the plantings in the east moat, Nigel Dunnett wrote: “The plants here were placed at low density around the path edges, and then the seed mixes were sown around them – it’s a technique I’ve used a lot to give some definite structure of deliberately-placed plants amongst the more spontaneous nature of the seed mixes. I used plants with a sensual character here – plants with tactile textures or aromatic plants. One of the most effective was Purple Fennel – the dark-leaved clumps were really effective early in the summer as the seeded plants grew up around them.” The swirling composite-wood pathway takes visitors towards the dragonfly sculpture by Quist.

Signage in the east moat recalls the allotment gardens of the past.

Even in my own meadows on Lake Muskoka north of Toronto, Canada (see my blog here on “Gardening Wild”), plantain (Plantago major), below, in the east moat, is a superb bumble bee plant in spring.

Brass and copper dragonflies fly over the moat, but the future plan is to bring real dragonflies into the moat with water features, as you see in the next photo.

This sign appears at the exit, presumably to greet visitors who might enter from the castle. But it promises a future for the moat: “We aspire to recycle rainwater to support flowering marshes, ponds, areas of food-related flowers and much more.” Fortunately a London-based son means we can and will revisit the Tower to see the development of this magical place. But I’m so delighted I experienced this late spring wildflower chapter in 2024.

Thank you for the informative blog and beautiful pictures.