Long ago, in the mid-1990s, I attended a presentation here in Toronto on “new urbanism”. It was focused on a development and planning approach that sees communities built according to principles of diversity of use and population; pedestrian and transit opportunities rather than being centred on automobiles; accessible public spaces and institutions; and a “celebration of local history, climate, ecology, and building practice.” (Source: Congress for The New Urbanism). One of the speakers was a local developer who was keen to build a community featuring many of the tenets of new urbanism. I was fascinated by his dream but secretly felt he would have a tough time competing economically with the treeless subdivisions of cookie-cutter, chock-a-block houses springing up north, east, and west of Toronto’s urban core. My city’s developers had been paving farm fields for years to build residential shrines to sprawl and the automobile. Yes, they were ‘affordable’ suburban homes for the middle-class in a growing metropolis of more than 6-million people, but any vestiges of natural or cultural heritage were erased in a bid to streamline lot servicing and maximize profits.

I was reminded of this a few days ago while reading in the paper about one of Toronto’s most successful subdivision builders. He demolished a $48-million house he’d purchased in seaside Florida a few years back in order to spend perhaps an equal sum to build an “ecomansion” for his family, utilizing net-zero energy but with enough garages for his many cars. And, of course, he flies there via private jet. I do not begrudge anyone their profits; he took a lot of financial gambles and lost money here and there along the way, especially during the 2009 recession. He is also a generous philanthropist. But it seems strange and counterintuitive to me that environmental principles are not part of an intelligent development business plan for every economic level of new home ownership.

So I was delighted last June during my annual Garden Bloggers’ Fling to visit the High Plains Environmental Center (HPEC) in Loveland, Colorado in the northeast part of the state. Here, an hour’s drive north of Denver in a 3000-acre mixed use development called Centerra, environmental principles are a major selling feature. Begun in 2001 by McWhinney Enterprises on land homesteaded and farmed by their family from 1866, Centerra includes retail businesses, office buildings, restaurants and residential neighbourhoods. The homes were built by McStain Neighborhoods, co-founded by green building pioneers and architects Tom and Caroline Hoyt. Both the McWhinneys and the Hoyts understood that there is a great cachet to building not just houses, but sustainable environments, in which people can feel connected to the land around them. Part of that initiative was the creation of the High Plains Environmental Center, occupying 100 acres of land surrounding two lakes comprising 175 acres of open water which are reserved for waterfowl. HPEC also manages 135 acres of common space belonging to the landowners in Centerra. Its educational visitor center was opened in 2017, a small building fronted by a lush meadow of native plants…..

…. including delicate blue flax (Linum perenne var. lewisii)……

…. and my favourite of all the penstemons, beautiful pink Palmer’s beardtongue (Penstemon palmeri).

Though we’d been told to make our way through the building, I had to stop for a few moments and enjoy the plantings in the parking lot, especially this border of labelled native perennials and shrubs…..

…. including gorgeous blue Rocky Mountain beardtongue (Penstemon strictus) and golden columbine (Aquilegia chrysantha var. rydbergii).

And as a photographer of bees, including bumble bees, I was delighted to spend a few moments tracking a new species for me, the Nevada bumble bee (Bombus nevadensis), which was busy foraging on the penstemon.

On returning from Colorado last June, the first blog I wrote was called Penstemon Envy. There are simply so many beautiful penstemon (aka beardtongue) species to see in early summer. This is pine-leaf penstemon (P. pinifolius).

Large-flowered beardtongue (Penstemon grandiflorus) with its semi-succulent leaves is one I grow at my cottage north of Toronto. For me, it behaves as a biennial, making its rosette the first year and flowering the second. Imagine how inspiring these native plants are for the homeowners in the neighbourhood!

Growing amidst rugged Colorado sandstone boulders was beautiful sulphurflower buckwheat (Eriogonum umbellatum), along with orange California poppies (Eschscholzia californica).

Prince’s plume (Stanleya pinnata) is a spectacular native plant that we would see in other Denver gardens on our fling. As well as being a larval host to two species of butterfly, it was also a traditional medicinal plant for many Native American peoples.

I passed the sign that marks Centerra’s certification as a Wildlife Habitat. And I wonder how many North American suburban planned communities could be brave and generous enough to view homebuilding as an ecological mission.

We were here to see the center but also to hear from its Executive Director, Jim Tolstrup. Originally from the Boston area, he’s been with HPEC for more than a decade, and we gathered around him in the Medicine Wheel Garden. This part of the center aligns very closely to Jim’s professional background, since he was “a founder and former president of Cankatola Tiospaye, a non-profit that provides material assistance to Native American Elders”. Though his role there, he developed life-long friendships with Native Americans and a perspective that informs much of the emphasis here at the center.

Jim told us about Centerra’s beginnings and its mission and said that the center and the community’s environmental ethos have actually become prime selling features for the development, where there are strict building and landscaping design guidelines. It’s promoted as “Certified Wild”, he said. This video is an excellent introduction to the High Plains Environmental Center.

This is the HPEC Master Plan from 2016 which gives a good overview of the site.

The Medicine Wheel Garden in which we stood was erected on consecutive Earth Days in 2018 and 2019.

It will be used for the local Thompson School District’s annual 3rd grade powwow and to host participants in the 400-mile Lakota ride along Colorado’s front range each summer.

It was freshly planted with species used by various Plains tribes as food, medicine or in ceremonies. The plants are labelled with their traditional Lakota names. Beyond the new Medicine Wheel Garden is The Wild Zone. Still being developed, it will serve as an outdoor classroom to foster a love of nature through play and self-directed learning. This section is called “The Nest Tree”.

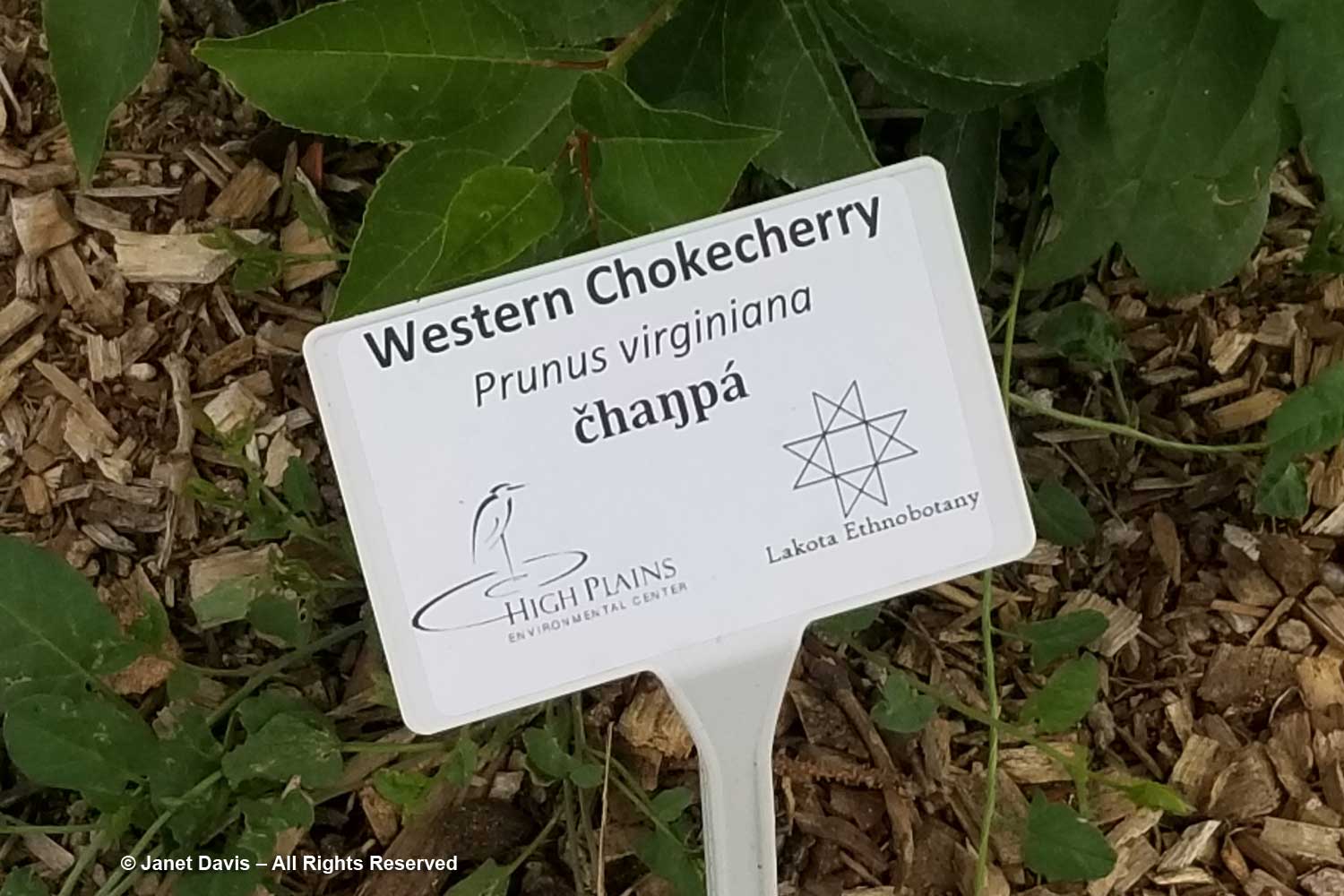

Here is one of the plant labels in the Medicine Wheel Garden….

…. and the plant with its unripe fruit. Chokecherry fruit was traditionally mixed with pounded bison meat and tallow in the making of pemmican patties or wasna.

Here is the label for yellow monkeyflower (whose Latin genus name Mimulus has been changed to Erythranthe). Check out that clay….

And here are the beautiful blossoms. The leaves of this species were cooked by the Lakota for food.

Fishing is allowed from the shore of Houts Reservoir and adjacent Equalizer Lake, with a licence from Colorado Fish & Wildlife. The lakes also support native waterfowl.

We toured the Community Garden…..

….. where members grow tomatoes, herbs and all manner of vegetables in neatly spaced raised planter boxes. In a normal year here, there are workshops on composting, pest management, propagation and other garden practices, as well as produce-swapping potlucks.

I wish we’d had more time to explore the Heirloom Fruit Orchard. I was surprised to learn that this part of Colorado has a buoyant fruit industry, and that the first cherry trees were planted here in 1864. Though the trees are young, this will be a wonderful spot. Among the old varieties of apples are Haas, Goodhue, Flower of Kent, Johnny Appleseed, Utter’s Red, Patricia, Gravenstein, Maiden Blush, Pitmaston Pineapple and Duchess of Oldenburg.

The greenhouses are used to raise native plants for plant sales and landscaping. Because of Covid, this year’s sales were held online with curbside pickup. Available plants included native hyssops, sages, columbines, milkweeds, buckwheat, gaillardia, sunflowers, beebalm, tansy aster, evening primrose, penstemons, ratibidas, goldenrods, vervains and Stanley’s plume.

We walked down The Promenade, a beautiful pathway through mixed plantings of Colorado natives. Imagine how inspiring this is for Centerra residents looking for plant design ideas for their landscapes.

Honey bees were all over the apache plume (Fallugia paradoxa). Not only is this drought-tolerant native shrub beautiful in flower, its fluffy, red seedheads are very decorative as well.

There were plants I’d never encountered before, like desert 4 o’clocks (Mirabilis multiflora).

I loved this beautiful western ninebark (Physocarpus monogyna), with Rocky Mountain penstemon at its base. It was the perfect pairing, and the perfect way to end an all-too-short visit to the High Plains Environmental Center.

*************

If you’re interested in First Nations culture, you might wish to read my blog on two days at Wanuskewin Heritage Park in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, the city where I was born.

Wonderful concept and rendition! The photos make you want to go there. Small world, I grew up in Saskatoon and my little friends and I used to wander along the river banks, without adult supervision (no helicopter parenting in those days), staying out all day and exploring, till we knew it was time to go home for dinner.

Thanks, Martine. Wow! Truly a small world. I left Saskatoon when I was 6 weeks old, but I did love seeing Wanuskewin and the river.