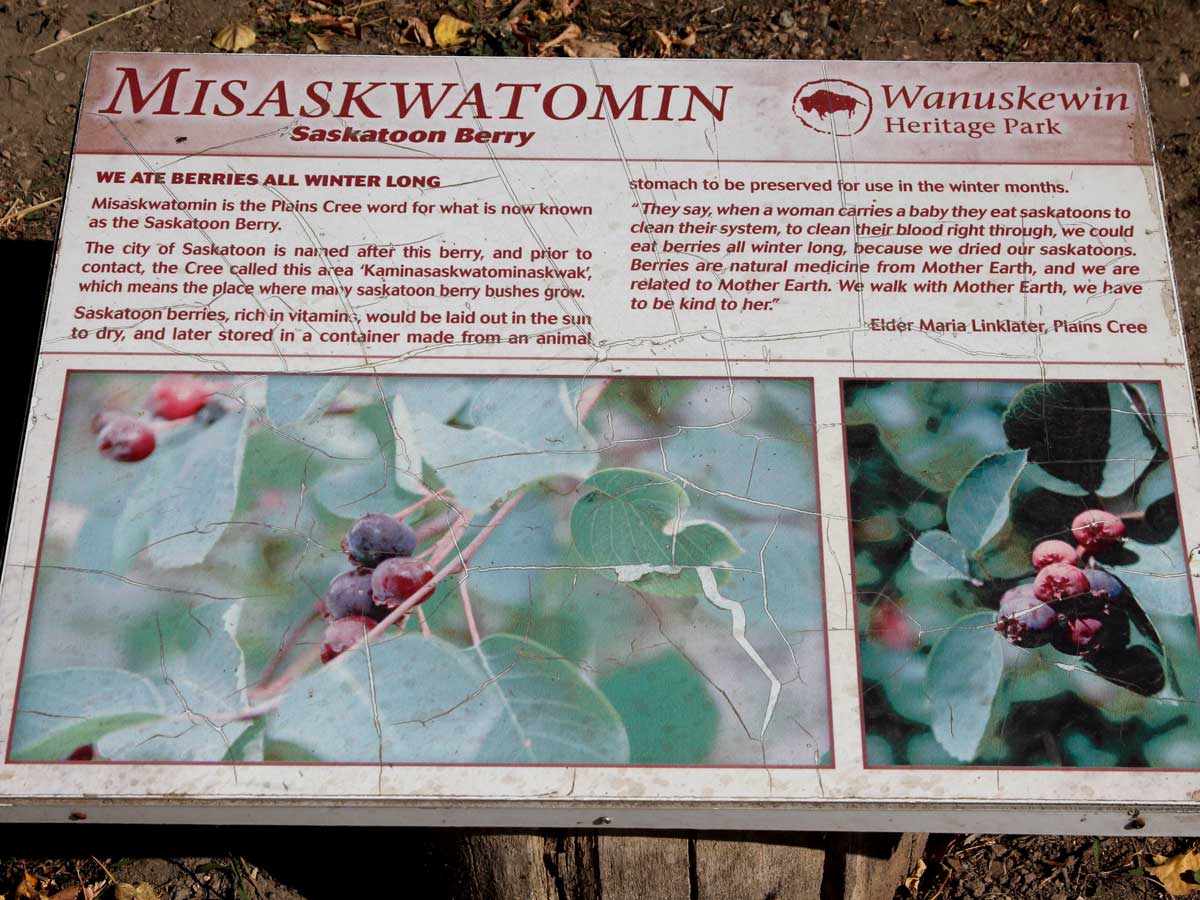

For thousands of years, the Plains Cree peoples called the place I was born Kaminasaskwatominaskwak, “the place where many saskatoon berry bushes grow”. It was named for the native shrub Amelanchier alnifolia, below, found throughout the Canadian prairies and called “misaskwatomin” by the Cree, for whom saskatoon berries were essential to their diet and often incorporated into the protein-rich meat-fat mixture (traditionally made with bison) called “pemmican”. My birth certificate says I was born in Saskatoon – a less tongue-twisting word for non-natives, beginning with English fur trader Henry Kelsey, the first European to arrive in the area in 1690.

My parents left Saskatchewan for Victoria, British Columbia when I was just 6 weeks old, so I never really gave much thought to the etymology of my home town’s name. When I was a little girl, my dad called our summer vacations to my Irish-born grandpa’s house in Saskatoon trips to “Saskabush” – and it would be decades before I knew there really was a ‘bush’ there, a special bush with a cloud of white flowers in spring and succulent reddish-blue summer fruit.

If, as some philosophers believe, your birthplace imprints itself in your subconscious, I suppose it’s no surprise that I have always been drawn to prairie, whether the tallgrass of the American Central Plains or our own mixed-grass Northern Plains. So when I was in Saskatoon earlier in September for a family funeral, I paid two visits to Wanuskewin Heritage Park. The last time I saw it was the last time I was in Saskatoon in 1996, 4 years after its opening. It has evidently weathered some institutional gales in its 25 years, but has found smoother seas now and is the recent recipient of generous funding that will see its facilities improved and its mandate increased. It has also applied for UNESCO designation.

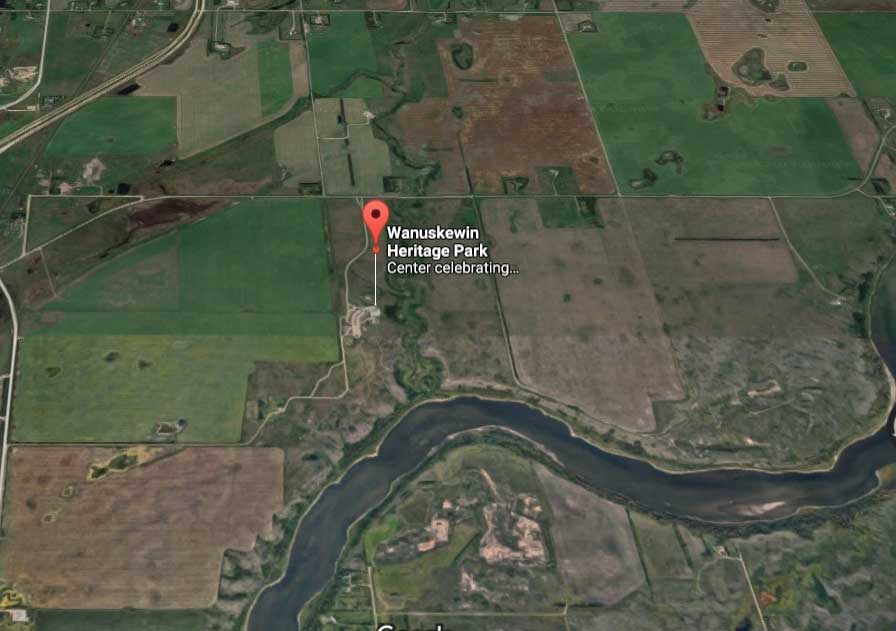

This is farming country and Wanuskewin is in the midst of it.

Across the road from the park is a wheat field and, in the distance, the big grain elevators of Richardson Pioneer Ltd.

Though Wanuskewin boasts myriad pre-contact archaeological sites representing 6000 years of Plains First Nations occupation, the land is not virgin prairie. In the early 1900s, it was homesteaded by the Penner family, whose name is still on the road sign nearby. They sold it in 1934 to the Vitkowski family, who farmed parts of it for almost a half-century before selling it in 1982 to the City of Saskatoon, which three years earlier had commissioned a 100-year master plan for the Meewasin Valley Authority (MVA) from Toronto architect Raymond Moriyama. Saskatoon transferred it to the MVA the following year and it was named a Provincial Heritage Property. In 1987, Queen Elizabeth visited Wanuskewin, designating it a National Historic Site; the interpretive centre and trails were opened in 1992. It is working now to fulfil the necessary criteria to receive the UNESCO World Heritage designation.

Friday, September 8, 2017

Wanuskewin is Cree for “seeking peace of mind” and it was with this gentle objective on my first visit that I drove my rental car down the driveway to the entrance.

I walked around the handsome Visitors’ Centre, a “Northern Plains Indians cultural interpretive centre” covering the seven First Nations in this part of Saskatchewan. I saw displays of clothing on the wall,…..

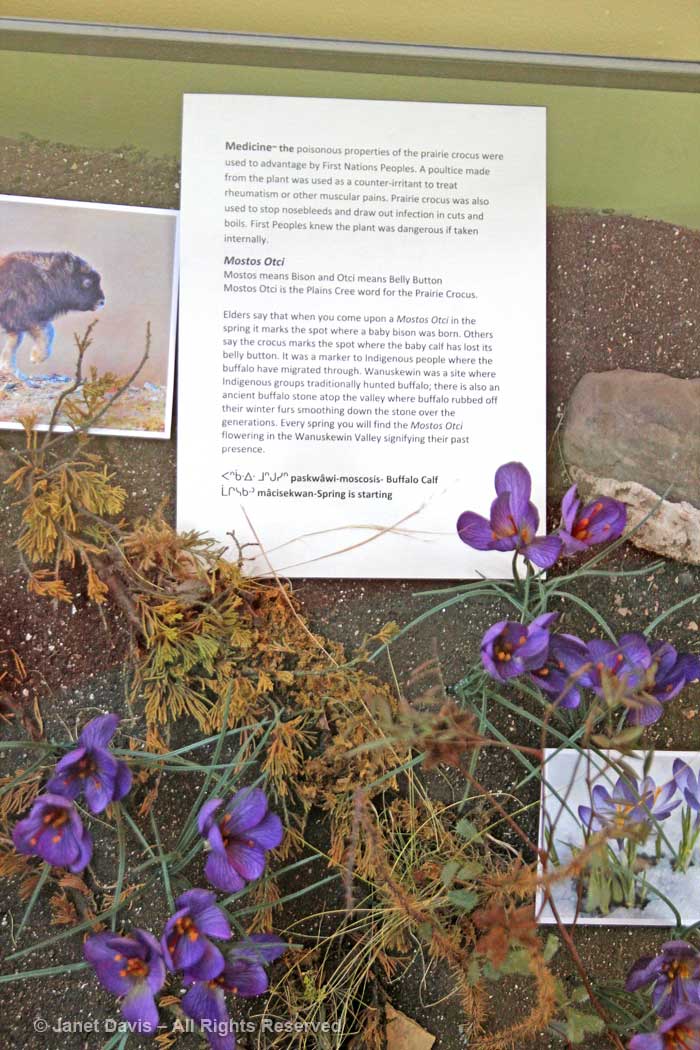

…a display case explaining the relationship of spring-flowering prairie crocus (Anemone patens) or “mostos otci” to the bison in First Nations natural history.

A tipi had been set up in the presentation lounge, just one of many interpretive programs, lessons and tours offered at Wanuskewin.

There was an impressive gathering of iconic bison nearby. A little boy visiting felt a tail and declared it “so soft!”

I read that a small bison herd is going to be returning to Wanuskewin soon – and are invoked in the park’s recent $40 million fundraising initiative #thunderingahead. Having been to the Nature Conservancy’s Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in the Osage Nation of northeast Oklahoma a decade ago, I know the powerful symbolism of these magnificent beasts, especially to the indigenous peoples whose ancestors co-existed with them, venerating them as they harvested them for food, shelter and clothing. The bison below, part of an introduced herd of 2500, was standing in big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), one of the keystone species of tallgrass prairie.

Wanuskewin’s reintroduced bison, on the other hand, will ultimately find a diet of mixed native prairie grasses (many newly introduced to meet the animals’ needs) and a few invasive interlopers, like smooth brome grass (Bromus inermis). They will find 240 hectares (600 acres) of plains and valley hugging the west bank of the winding South Saskatchewan River, about 5 kilometres north of Saskatoon. And they will share the prairie with hundreds of thousands of visitors each year who, like me, set out on a trek of discovery.

Out I went into the late summer prairie heat, taking a trail that led past the recreation of an ancient buffalo pound once located at this spot….

……down into the valley to the Tipi Village in a grove of trembling aspens..

I carried on up the hill behind the tipis, passing a few vivid painted reminders of the Plains people who might have camped here at one time…..

…… or planted crops and gathered grain.

From the top of the hill, I looked back at the Visitors’ Centre. Designed by the architecture farm aodbt, Its roof peaks are intended to suggest tipis.

And up here, I had my first glimpse of one of the distinctive plants of the Central Plains: wolf willow (Eleaegnus commutata). Some people call this suckering shrub ‘silverberry’ for the fruit that follows the small, fragrant, yellow flowers. It feeds grouse and songbirds, but it has also fed the imagination of artists and writers.

I am currently reading Wallace Stegner’s classic Wolf Willow (1955), centred on the Tom Sawyer-like years of his childhood spent in the town of Whitemud (Eastend) in Saskatchewan’s western Cypress Hills where his parents had a small home in the village and homesteaded a 320-acre wheat farm near the Montana border. I love Stegner’s thoughtful prose (he became head of the Creative Writing department at Stanford and a respected author of books about the American west) and while the multi-faceted literary approach he uses in Wolf Willow in exploring his own evolution as a person is brilliant and has generated a trove of critical analysis, what he failed to find in digging into his past — though he traces the history of the Métis masterfully — is what Wanuskewin is all about. It is here to tell a great story about the people Stegner barely noticed, other than the little Métis boys he played with, the people who can trace their lineage on the prairie for thousands of years before Europeans arrived to raise cattle and grow wheat.

From the high vantage point, I gazed down onto Opimihaw Creek through a leafy bouquet of Saskatoon berry already taking on its tired autumn hues of rose and gold. Flowing through the valley from the mighty South Saskatchewan river nearby, Opimihaw has given sustenance to this place and its people and wildlife for millennia.

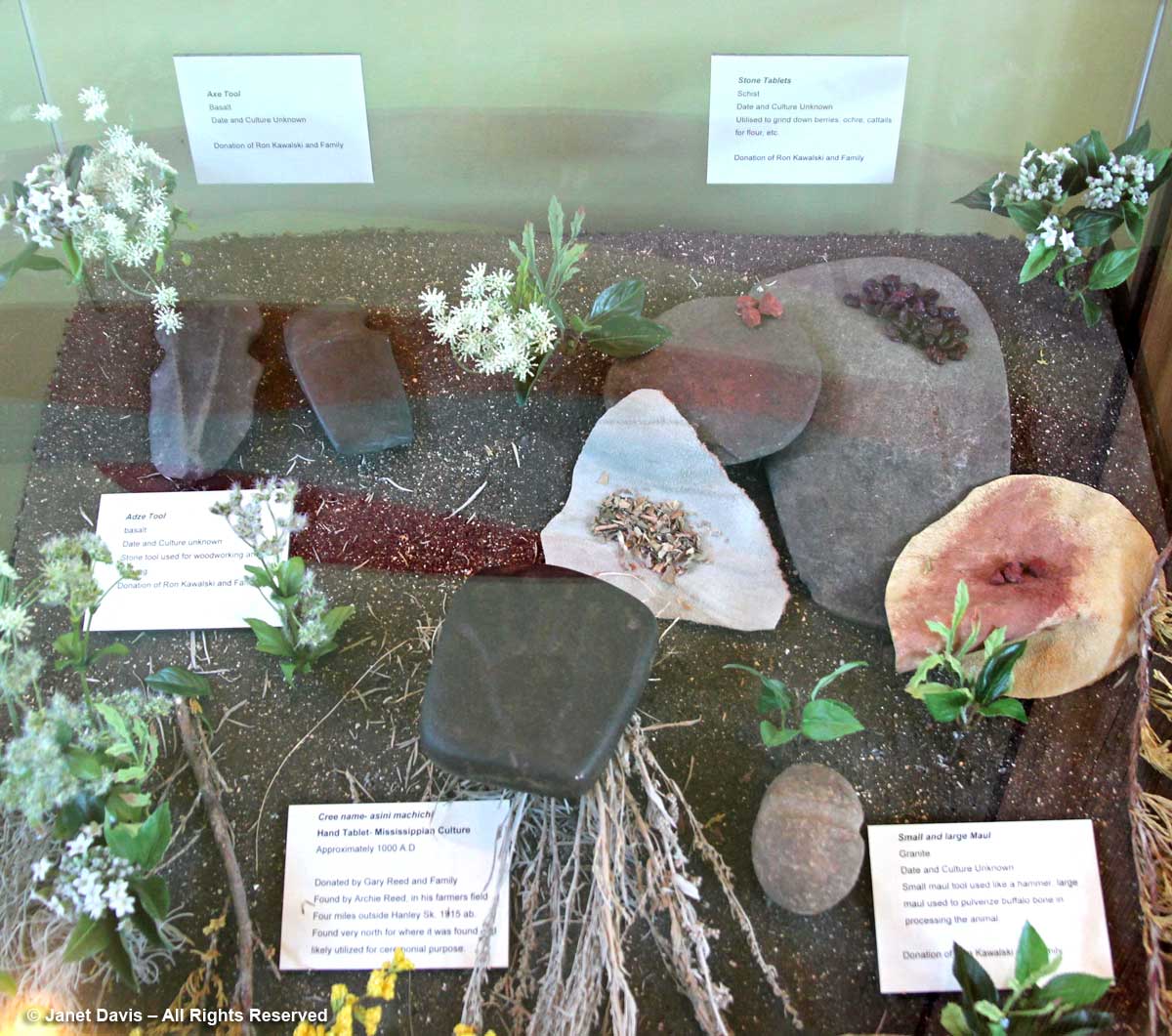

As I walked along the rise, I saw lichen-spangled rocks nestled in the tawny prairie grasses like sculpture.

Rock, of course, was an essential part of life for Plains Indians, who used basalt, granite and schist to fashion the implements that have been found in archaeological digs at Wanuskewin and nearby, as shown in these donated artifacts in the Visitors’ Centre.

I climbed back down into the valley, surprising a great blue heron that had been fishing in the creek.

I looked up and saw robins conferring noisily in the branches of a dead tree.

In the damp valley near the creek were sandbar willow (Salix interior)…..

….. and snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus) which is one of the dominant shrubs at Wanuskewin in both damp and dry places.

There were lots of rose hips; these are likely from Rosa acicularis, but low prairie rose (R. arkansana) and Woods’ rose (R. woodsii) also grow here.

I gazed back at the Visitors’ Centre through the changing fall leaves of Manitoba maple or box elder (Acer negundo), one of the principal tree species in the valley….

…. and past the crimson fruit of firebelly hawthorn (Crataegus chrysocarpa)…

…. and silver buffaloberry (Shepherdia argentea). Like wolf willow, this shrub is a member of the Oleaster family, Elaeagnaceae.

The Saskatchewan prairie, like the rest of North America, has not escaped the invasion of buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), which was introduced from Europe in the early 19th century.

I climbed back up the rise onto the dry prairie and looked out through a scrim of fall-coloured shrubs and trees at the South Saskatchewan River flowing away from me. It flows 1392 kilometres (865 miles), originating at the confluence of the Bow and Oldman Rivers in Alberta with their Rocky Mountain glacial water. It flows under multiple bridges in Saskatoon, beneath Wanuskewin’s tall bluffs and eventually joins with the North Saskatchewan River about 40 miles east of Prince Albert to form the Saskatchewan River.

I was now on the ancient Trail of the Bison, and though ‘civilization’ lay just across the river, I marveled at the ‘bigness’ and ’emptiness’ of the prairie behind me. I turned and looked the other way down the river towards Saskatoon, at the undulating bluffs and the grassy floodplain flats on the shore.

It had been a hot summer and the vegetation was parched, but here and there I saw the odd wildflower, like spotted blazing star (Liatris punctata)….

….and prairie coneflower (Ratibida columnifera)…

….and tiny rush-pink (Stephanomeria runcinata) with its wiry stems.

I saw the cottony seedheads of long-fruited thimbleweed (Anemone cylindrica).

But it had been a long day, beginning with my 4:30 am wakeup in Toronto, the flight to Saskatoon, and three hours tramping the prairie. I was tiring and ready to head to the hotel. As l made my way down the trail to the Opimihaw Valley and back towards the Visitors’ Centre, I was careful not to step off the path, because those red leaves with the telltale “three leaves let it be” were the prairie variety of poison ivy (Rhus radicans var. rydbergii).

I was sad not to have seen the famous Medicine Wheel, but vowed to try to return after the weekend. As I was leaving, a staff member came up and told me there was about to be a hoop dance performance. I met young Lawrence Roy Jr., below, in the Visitors’ Centre lobby and decided to head out to the amphitheatre to watch him.

This is my video of Lawrence’s performance (with a little wind interference – it’s hard to capture sound at Wanuskewin without the relentless wind):

And then it was back to the hotel and family.

Monday September 11, 2017:

When I returned to Wanuskewin, the wind was whipping the prairie so fiercely, I put my sun hat back in the car for fear it would fly away. Fortunately, it wasn’t sunny as I set out on the Circle of Harmony trail towards the Medicine Wheel. What you cannot appreciate from the photo below is how that expanse of grass was rippling like a storm-tossed ocean, and the sound of it was violent and thrilling at the same time. (If you read my blog to the end, you can view a video I made to try to capture the rhythmic movement of the grasses.)

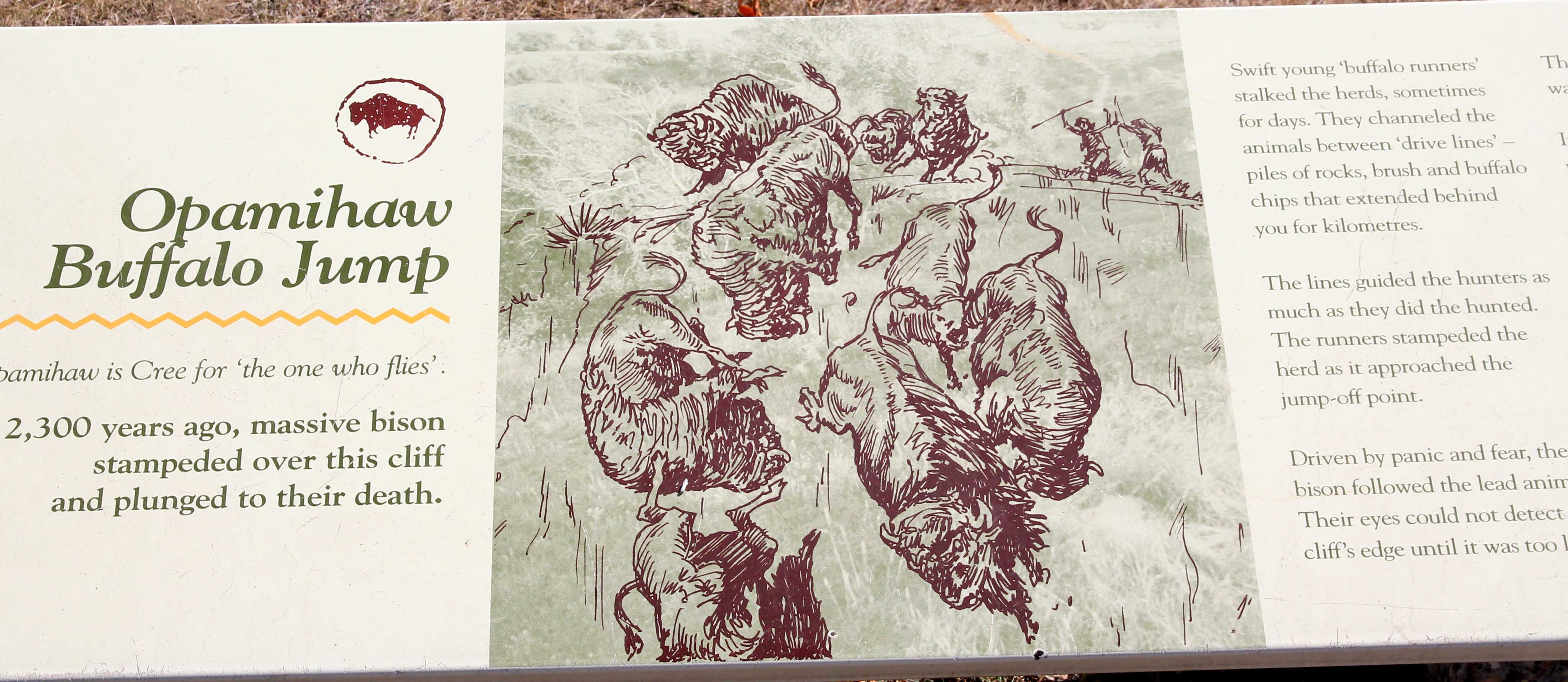

As I walked along a steep embankment with a spectacular view of the Opimihaw Valley (sometimes spelled Opamihaw) and the high point opposite where I’d stood a few days earlier overlooking the river, I realized I was standing on the site of the ancient buffalo jump.

Can you imagine, some 2300 years ago, being somewhere nearby as young ‘buffalo runners’, who had channelled herds of these massive animals along ‘drive lines’ of rocks and brush (the driveway into Wanuskewin is situated on the drive line), often for a mile or more, aiming the terrified animals at this cliff where they stampeded them over its edge into the valley? Other members of the band waited in a clearing below to kill those bison that had not died in the crush of the fall, before skinning them to utilize the hide, meat and bones. Life at Wanuskewin revolved around the bison.

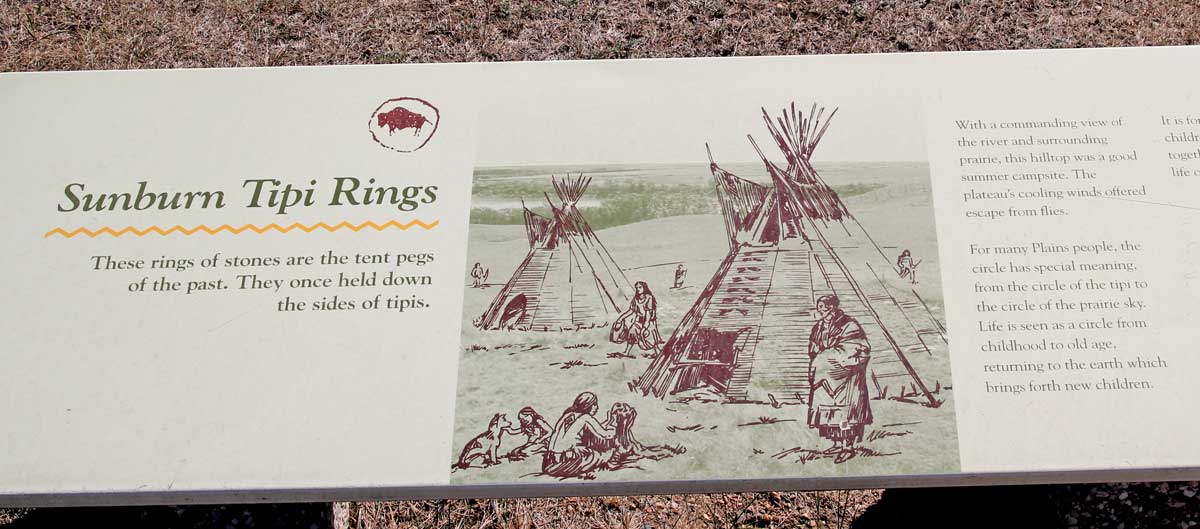

Before long, I came upon the ancient Sunburn Tipi Rings site, with its magnificent 360-degree views.

As the interpretive sign says, it was an excellent place for a summer encampment, its position on the plateau offering cooling winds in summer and a commanding view of the river.

Not far away was the Medicine Wheel, arguably the most important archaeological find at Wanuskewin. This arrangement of boulders has been dated to more than 1500 B.P. and is one of just 70 documented medicine wheels in the northern U.S. and southern Canada (and considered to be the most northerly wheel in existence).

Each is different, some with a single hoop arrangement of boulders; others with a double hoop or spokes emanating from the centre. Some refer to astronomy (like Wyoming’s Medicine Mountain wheel which measures the 28 days of the lunar cycle); others attach different symbolic meaning to the four directional quadrants. Wanuskewin’s Medicine Wheel, whose boulders (below) were mapped c. 1964 , is still used for sacred ceremonial gatherings.

Wanuskewin has benefited from the work of Saskatoon archaeologist Dr. Ernie Walker, who has supervised digs here since the early 1980s.

I decided to walk down the trail to the valley, through the aspen forest and along the river. Damming of the South Saskatchewan over the decades has lowered the water level, so that some of the sandbars are now permanent.

With my telephoto lens I could see the wind-whipped whitecaps as the river curved under the bluffs.

The view of the Visitors’ Centre from the valley was spectacular. I realized I was hungry, and decided it was time to head back there again.

I was windswept, sunburnt and happy – time for a photo to remember the mood! And I was very ready for some lunch!

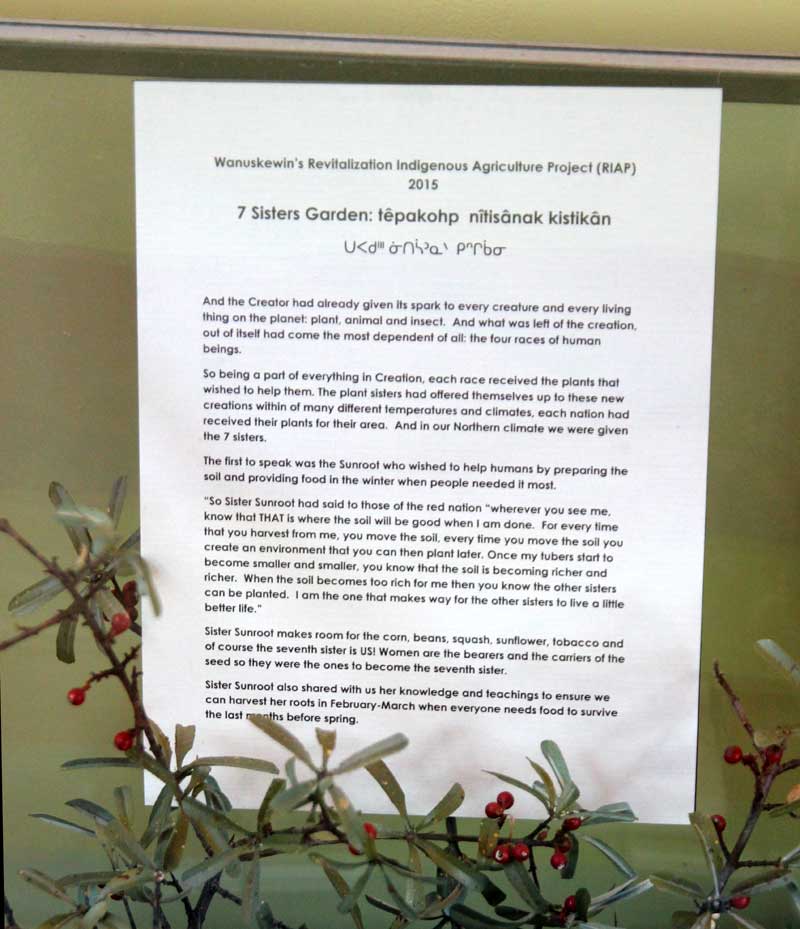

As I approached the centre, I decided to pay a visit to the adjacent 7 Sisters Garden.

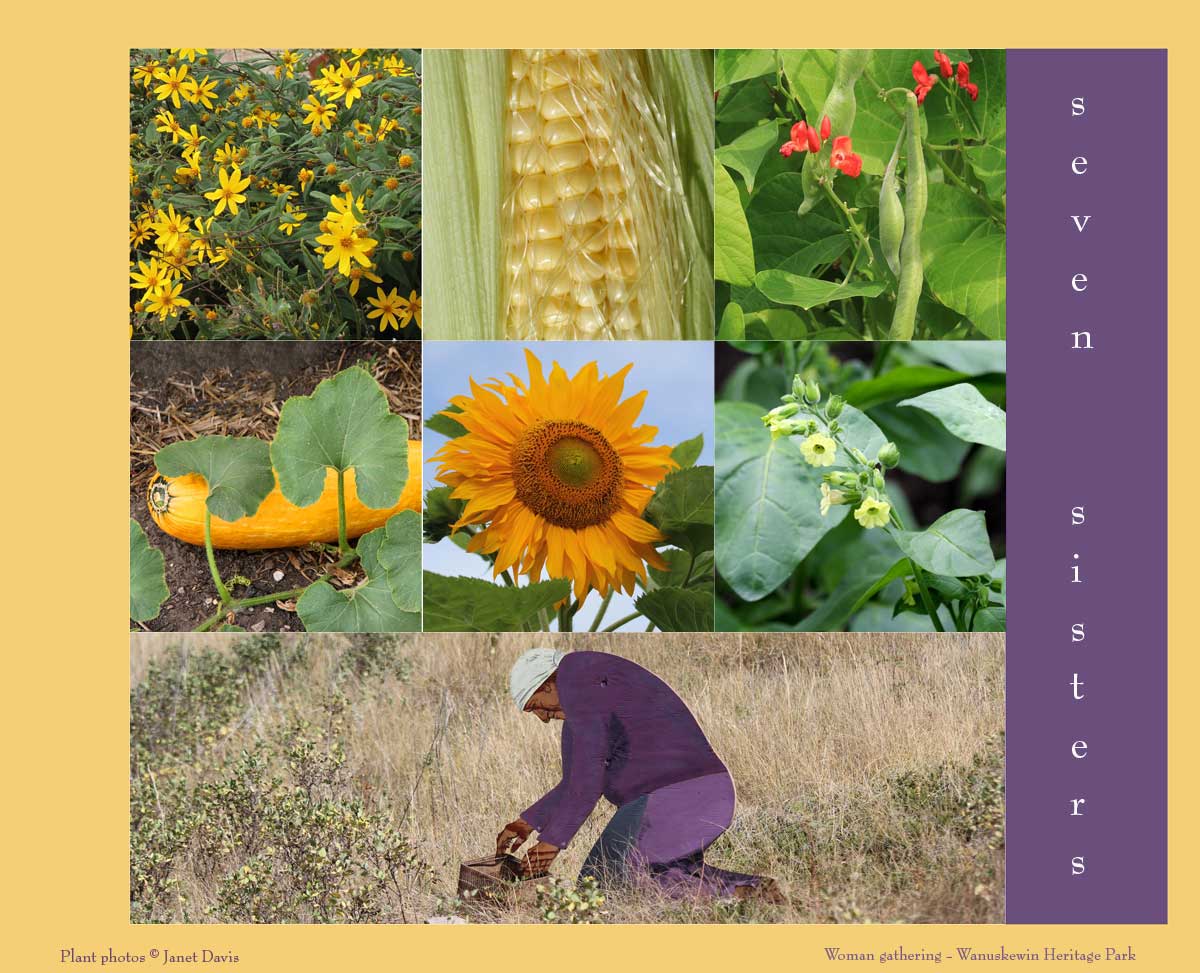

An interpretive display in the centre explains the identity of the seven sisters….

….which I’ve arranged in a montage below. Clockwise from upper left, 1) sunroot (Jerusalem artichoke); 2) corn; 3) beans; 4) tobacco; 5) sunflower; 6) squash; and 7) as the young woman in the centre said to me: “Us!” (I’ve taken the liberty of using the painted figure near the Tipi Village to illustrate ‘Us!’.)

Out in the garden itself, I was interested in the traditional 3 Sisters method of planting: using a combination of dent corn, beans and squash. Given its modern iteration, the heat and drought meant that a sprinkler was watering the tall corn. Goldfinches darted from sunflower to sunflower, eating the seeds that had started to ripen.

Cornstalk as a bean trellis! Isn’t this a wonderful idea?

Inside, I ate a delicious lunch of chicken & rice soup with bannock and a steaming cup of Saskatoon berry tea.

As I finished, I heard jingling bells and walked to the presentation lounge to watch T.J. Warren, originally from Arizona’s Diné nation, now working as an ambassador for First Nations culture in Saskatoon, perform a traditional Prairie Chicken Dance.

This is the video I made of T.J. dancing and talking about the components of his regalia.

And, finally, this is my video incorporating elements of both days at Wanuskewin. I hope that if you visit Saskatoon, you will find the time to walk its plains and valley. I promise it will bring you ‘peace of mind’.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zAx6v6nQ_ow