When we arrived in New Zealand in early January, my knowledge of the country extended to the Wikipedia entry I read on the flight from Los Angeles to Auckland, much of which was skewed to the back-and-forth of modern politics. In other words, I didn’t know much at all – and in the post-Christmas rush to get away on a long trip, I thought that much research was fine. Fortunately, it would only be a matter of days before my understanding of the place began to expand.

For the Māori, who were the first humans to inhabit the country when their forebears arrived from eastern Polynesia around 1280, a date determined by archaeologists from a 1964 dig on the Coromandel Peninsula near present-day Auckland, which revealed the fishing lure, below, made of a tropical black-lipped pearl shell from East Polynesia and brought here in a waka (canoe) during settlement……..

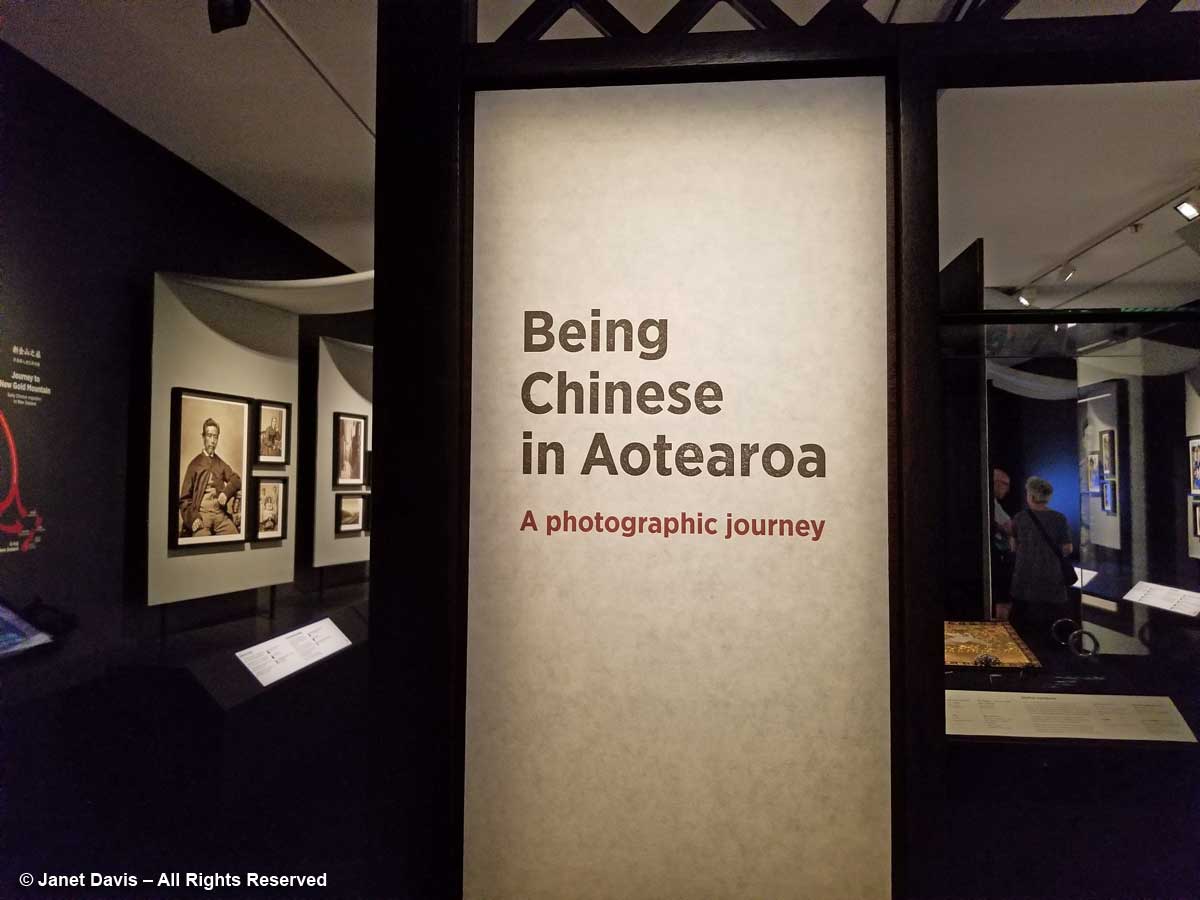

…..”New Zealand” isn’t the name they gave the country. Instead, they called it Aotearoa, “land of the long white cloud”. It is the name that I first saw in the exhibit below, at the Auckland Museum, on our first day of touring.

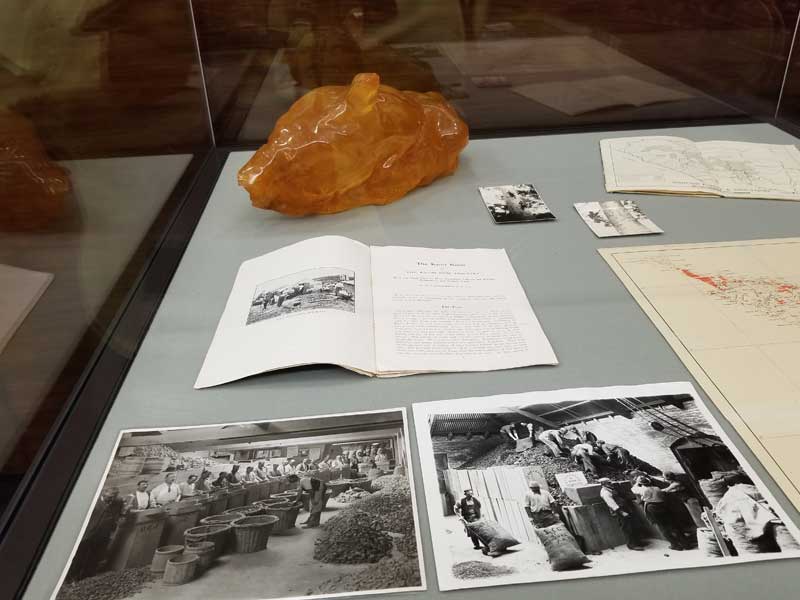

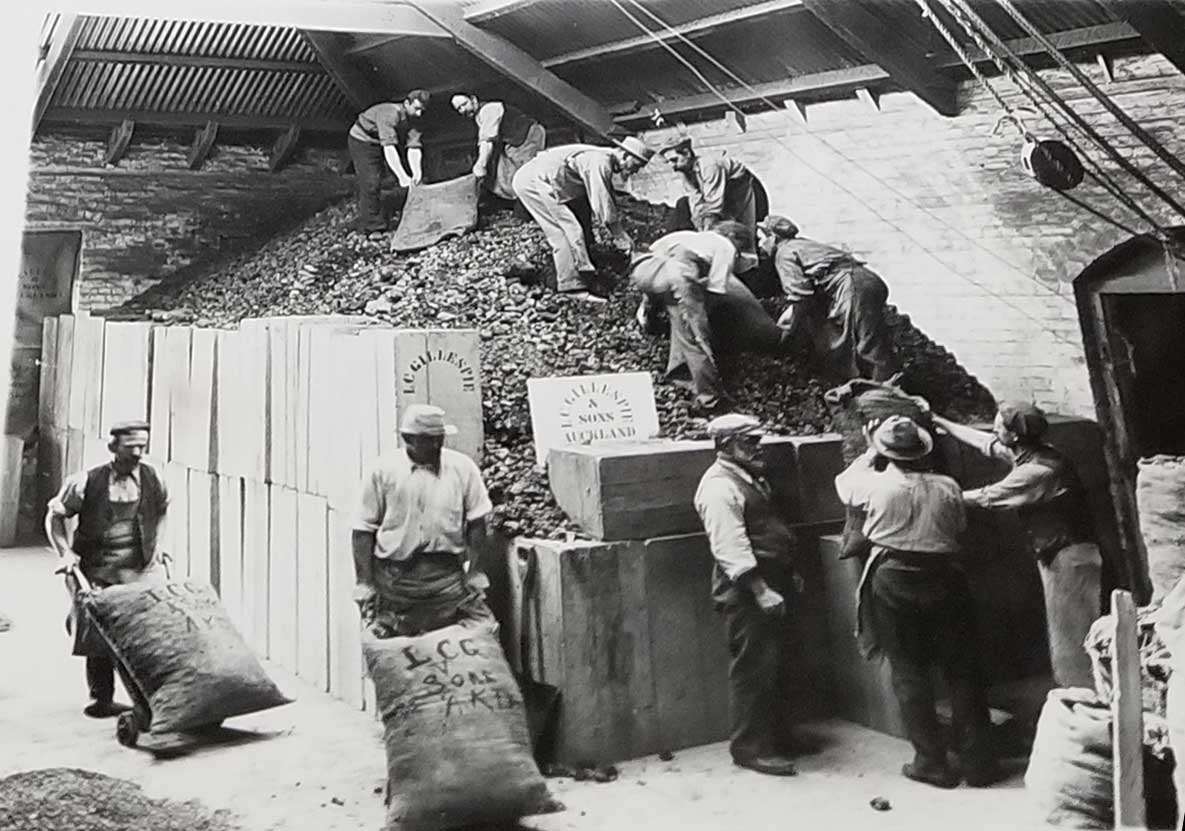

Interestingly, that exhibit of the Chinese immigrants who came to seek their fortune in the country beginning in the late 19th century featured a display case, below, devoted to the kauri gum industry, built on the exudate of the giant kauri trees (Agathis australis) that once formed large tracts of forest in New Zealand. A visit to one of those forests was on our itinerary on this fourth day of the American Horticultural Society’s “Gardens, Wine & Wilderness Tour” – and you will find it further down in this blog!

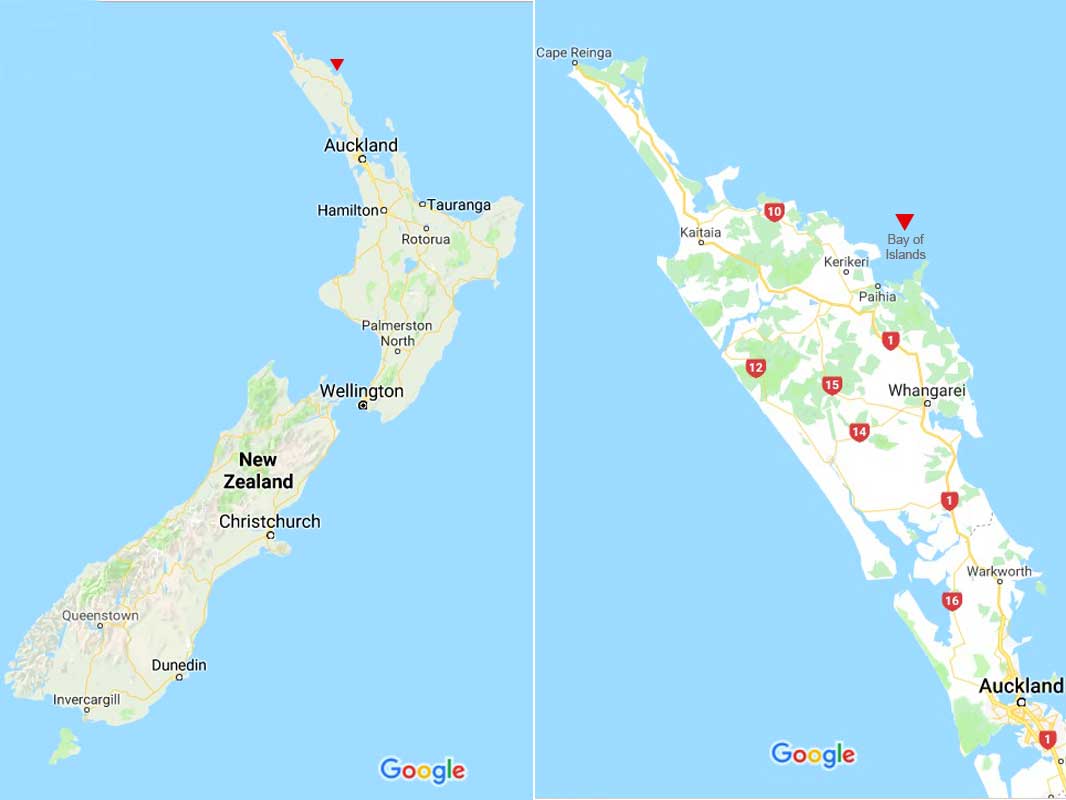

We were now in the Bay of Islands region of the North Island in the seaside town of Paihia. On the map below, you can see it in the upper right. This part of New Zealand is arguably the warmest, being closest to the equator. Over the next few weeks, we would travel to Fiordland in the far southwest of the South Island, which is closest to the Antarctic and therefore has the coldest winters.

On our arrival the afternoon before, we’d walked along the beach…..

….where many small offshore islands give the region its name……

….on our way to take a short ferry trip to the town of Russell across the bay for dinner. On the pier, we watched as fishermen brought in a giant blue marlin, estimated to be 375 pounds (170 kg).

It was only when we returned after dinner that we noticed the big marlin sculpture at the ferry dock dedicated to the American novelist Zane Grey (1872-1939), who’d put Paihia on the world travel map for its abundant game fishing when he built the Zane Grey Sporting Club on nearby Urupukapuka Island in the Bay of Islands. He also penned a book called Tales of the Angler’s Eldorado, about fishing in New Zealand.

Hongi Hika and the Missionaries

Today’s tour day began with lovely birdsong outside our window in the lush courtyard garden of the Scenic Hotel.

After breakfast we set off with our special guide for the day, Kena Alexander, our Māori culture specialist. He taught us the traditional greeting, “Kia ora”, which means roughly “be well”. He also told us about the Māori alphabet, which contains 15 letters: 10 consonants (including 2 two-letter diagraphs) and 5 vowels. They are a, e, h, i, k, m, n, ng, o, p, r, t, u, w, wh.

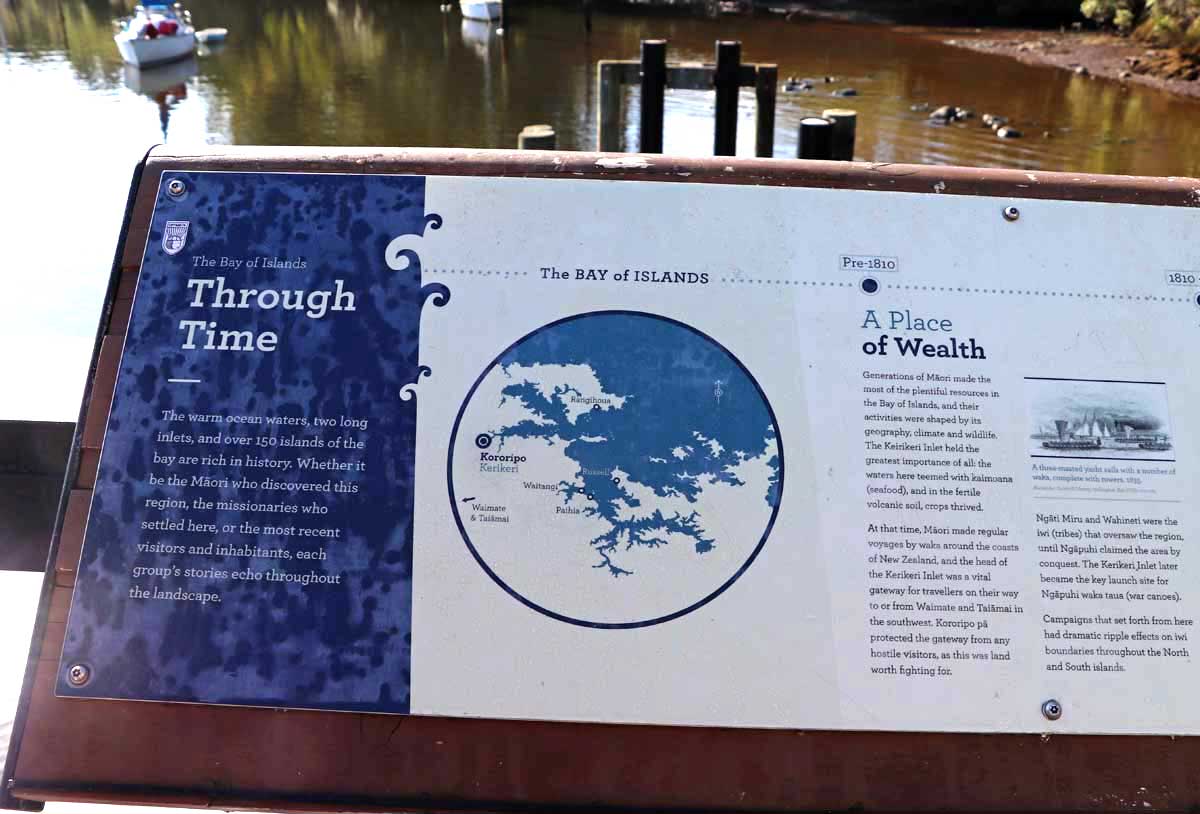

Soon we arrived at Kororipo Heritage Park, the site of important 19th century interaction between northern Māoris and early European visitors.

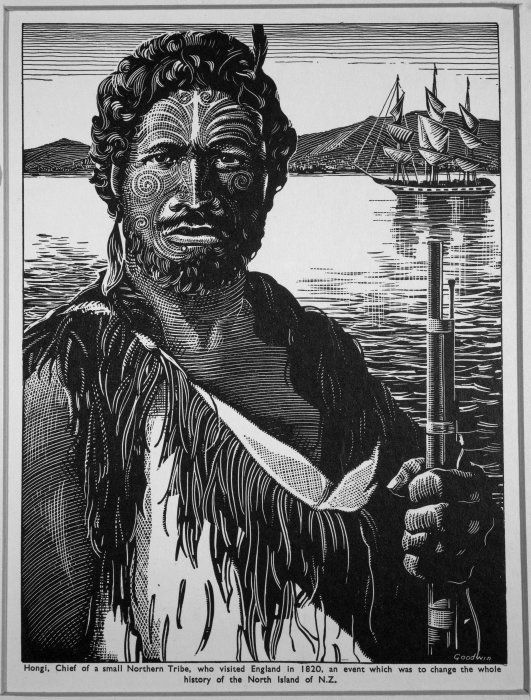

By the time Captain James Cook visited the Bay of Islands on voyages in 1770 and 1777, Māori had been in the region for almost four centuries. But it was Hongi Hika (below middle), the fierce rangatira (chief) of the Kororipo Pā (a pā is a fortified village) in the Kerikeri Inlet who arranged for the protection of the pākehā (Europeans) who wanted to establish a mission here. In 1814, along with another chief, his brother-in-law Waikato, below left, he accompanied English missionary Thomas Kendall, below right, to Sydney Australia. Here, while studying agricultural methods and inviting Samuel Marsden to establish a mission at Pa Kororipo, he would also buy the muskets and ammunition that would trigger the Musket Wars of the next three decades and cement his reputation as the most fierce of the Māori rangatiras. Six years later, he would travel to England, where King George IV would present him with mail that he later wore into battle.

Hongi Hika liked to say he was born in 1772 (though later research proved him wrong by a few years), the same year that French Explorer Marion Du Fresne was killed and cannibalized, along with 26 of his men, in Te Hue Bay in the eastern part of Bay of Islands. The French sailors’ crime in the eyes of the Ngāpuhi iwi (tribe), who were their hosts, was their insistence, despite being warned, on using large nets to fish a beach on which the bodies of tribal ancestors had once washed up, a beach their descendants considered sacred. Three decades later, Hongi Hika used muskets to wage war against competing tribes in the area, after which they would follow the custom of eating their slain enemies, thus absorbing their manu or prestige, while the missionaries under his protection could only look on in disapproval. The practice was not new to the pākehā. In 1769 Captain James Cook and Joseph Banks aboard the Endeavor had witnessed it and Cook waxed philosophical on the topic in his journal. As the New Zealand government’s website notes: “He is credited with showing forbearance, restraint and a depth of understanding (he had a more moderate view of cannibalism, for example, than most of his crew) that put initial relations between Māori and Europeans on a sound footing, despite episodes of bloodshed on the first and second voyages”.

In January 1826, Hongi Hika was shot in battle on the banks of the Hokianga River. His injury meant he could no longer lead his iwi. In 1827, he was visited by Augustus Earle, who was the draughtsman aboard the HMS Beagle. Along with the young naturalist Charles Darwin, Earle was visiting the Bay of Islands, making beautiful paintings of the scenes he found, such as Hongi Hika, below, bedecked in white feathers and sitting with members of his tribe as he received the pākehā visitors. He would die in March 1828.

Today, the Kerikeri Mission Station consists of two buildings. The first, Kemp House (below), is New Zealand’s oldest building, erected in 1822.

A large jacaranda tree was in full bloom beside the house…..

…and on the other side was its historic garden, where we chatted with the volunteer working there.

The Stone Store, the country’s oldest stone building, was built in 1835. Interestingly, it was once a kauri-gum trading post…..

….. and it was now time to leave Kerikeri and head inland to see the iconic trees from which that gum was harvested.

In the Kauri Forest

Half an hour later, we arrived at the protected Puketi Forest to do the short Manginangina Kauri Walk. The 20,000-hectare (49,420 acre) Puketi-Omahuta forest is one of the best examples of the sub-tropical rainforest of the North Island.

Our guide Kena remained outside. He shared with us that his own family tribe had not been defeated in the New Zealand Wars (see the Waitangi treaty later in this blog) and had not ceded sovereignty over the lands in which the forest resides. Since they continue to be engaged in a legal action with the government, he does not enter the disputed land.

Boardwalks threaded their way under the towering trees in this sub-tropical forest…..

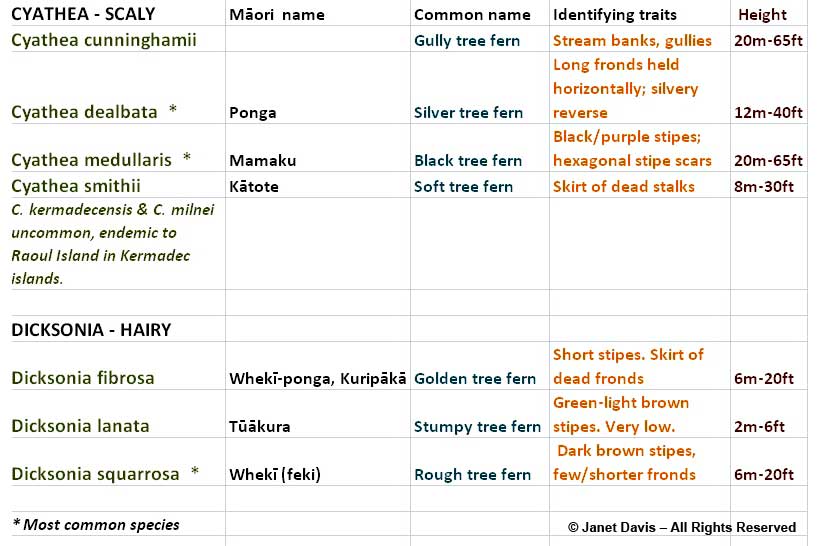

….. where tree ferns and nīkau palms share the understory.

Look at these wonderful trees! In perfect conditions, their ghostly, pale trunks can achieve a massive girth. New Zealand’s largest tree is the kauri known as Tāne Mahuta in the Waipoua Forest, estimated to be 1,250-2,500 years old. Although its height 45.2 m (148 ft) is fairly modest, its 15.4 m (50 ft) girth and massive volume makes it the third largest conifer on the planet, after California’s sequoiadendrons and sequoias.

The kauri (Agathis australis) is endemic to the northern part of the North Island, i.e. north of 38°S. A conifer, it is in the Araucacieae family and distantly related to the Norfolk pine and monkey puzzle tree. Its straight bole made it valuable to the early Europeans as ship spars and masts, and it’s estimated that logging beginning in 1820 had by 1900 reduced the kauri population, originally 12,000 square kilometres, by 90-percent. Today, only 3-percent of the original forests remain. The government finally banned commerical kauri logging in 1985. As New Zealanders became aware of the great losses that had been inflicted, protected forests like Waipoua (1952) and Puketi were set aside, resulting in spectacular scenes like the one below, which I captured on our short visit to Puketi.

Among the many epiphytic plants is “perching lily” or kowharawhara (Astelia solandri) – the sole member of the genus that has this aerial habit.

In this forest, fallen kauris become part of the undergrowth……

…..however, there are kauri swamps in Northland where the anaerobic qualities of peat bogs and ancient salt marshes have preserved massive trunks that toppled eons ago – some carbon-dated to more than 50,000 years – often still bearing their attached green leaves. Sometimes referred to as “sub-fossil” kauri, they generated a swamp-extraction kauri timber industry beginning in the 1980s, sometimes by unscrupulous players, that saw wood selling for up to $10,000 per cubic metre, mainly to China. But these ancient kauris have also become a valuable aid to scientists, their annual growth rings a barcode of climate change over a vast number of years.

Apart from logging and swamp extraction, the kauri became most famous in colonial New Zealand for its gum, used and exported at the time for floor varnish and linoleum. Though the kauri is evergreen, like all rainforest trees the leaves shed periodically, accumulating at the base of the tree and eventually forming some 2 metres (6 feet) of soil there. As the tree exudes sap, it crystallizes, slowly forms chunks, then falls to the ground, becoming buried in the soil. As I mentioned at the top of this blog, gum harvesting generated a kind of boom that saw some 20,000 gum-diggers working the Northland forests and swamps by 1890: mostly Maori, Chinese, Malaysian and Yugoslav. Climbing a kauri tree to cut it and cause the tree to exude the gum was a special skill. And digging the swamps for fossilized gum was the worst kind of labour.

But it was lucrative: by 1918, the New Zealand kauri gum industry had exported product worth the staggering sum of £18,224,107.

In the Te Papa Museum in Wellington a few weeks later, I would see a spectacular sample of kauri gem embedded with insects. The oldest kauri gum, found in coal deposits, is some 50 million years old.

Today, seeing sap dripping at the base of a kauri tree is often a sign of kauri dieback disease. Visitors to the protected forests are requested to stay on the walkways, since the villain is a soil-borne organism, an oomycete (Phytophthora agathidicida) that causes root rot, defoliation and death. There is no known control. I saw such a tree at Puketi, its lower trunk riddled with cankers dripping with sap.

Our short, lovely stop at Puketi over, we were soon back on the road with Kena to pay a visit to his own tribe’s marae.

Visit to a Māori Marae

As we drove, I noted out the bus window dairy cattle grazing where a native brown sedge (Carex sp.) had popped up in the green forage. It reminded me of what our horticulture tour guide Panayoti Kelaidis, outreach director at Denver Botanic Gardens, had said to us: “New Zealand’s hills should be brown, not green.” Before cattle were imported for New Zealand’s thriving dairy industry, there were no green pastures; that changed with the concomitant use of green Eurasian grasses for animal forage.

After arriving at Kena’s marae, a rectangular plot of cleared land that is traditionally a meeting place providing social or spiritual needs to the Māori, we were called inside the beautiful wharenui (communal house), below, to participate in a traditional greeting ceremony or pōwhiri. We removed our shoes and entered, the women and men sitting in separate sections while we listened to the readings and to a speech from the elder. Photos were not permitted during the protocol, but it was a very moving ceremony, as we joined our Māori hosts in observing a silent remembrance of our own ancestors. At the culmination, Kena and his wife sang a song to us, and we in turn sang back to them (well, we had rehearsed Home on the Range and sounded quite good, I thought.)

The official ceremony now over, Kena pointed out the features of the wharenui, which we were free to photograph. The building interior represents the bosom of a beloved ancestor or spiritual figure. The carved ceiling ridge-beam or tāhuhu represents the backbone, while the painted rafters or heke represent the ribs.

The stunning designs on the heke, below, are traditional kōwhaiwhai. The symbolism is specific to each tribe’s environment, lineage and history, and might incorporate the koru (fern crozier), ngaru tai (ocean waves), fish or birds.

Carved wood figures called poutokomanawa appear on supporting posts. With their flashing eyes made of puau shell from sea snails, they represent tribal ancestors.

Kena happily answered our questions after the ceremony, then it was time to head back to our hotel to rest up before our next Māori cultural experience later that day.

As we drove, Kena pointed out a hilltop pā adjacent to the highway, one of many that can still be seen in Northland. So interesting to see these landforms and imagine how they functioned as self-contained villages hundreds of years ago.

An Evening at the Waitangi Treaty Grounds

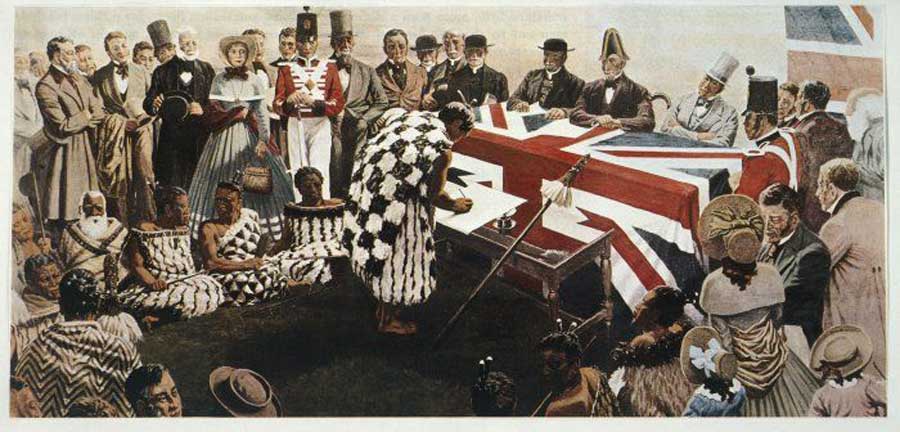

On February 6, 1840, representatives of the British government and a group of northern Māori chieftains met at this lovely spot overlooking the Bay of Islands in Paihia…..

… to sign The Treaty of Waitangi. Copies of the treaty were then carried around New Zealand and ultimately signed by more than 500 chiefs, including 13 women. The British wanted the opportunity to acquire land; the Māoris wanted protection from the French. As it says on Wikipedia: “The text of the Treaty includes a preamble and three articles. It is bilingual, with the Māori text translated from the English. Article one of the English text cedes “all rights and powers of sovereignty” to the Crown. Article two establishes the continued ownership of the Māori over their lands, and establishes the exclusive right of pre-emption of the Crown. Article three gives Māori people full rights and protections as British subjects. However, the English text and the Māori text differ, particularly in relation to the meaning of having and ceding sovereignty. These discrepancies led to disagreements in the decades following the signing, eventually culminating in the New Zealand Wars.”

Though the treaty was considered by many to be the founding document of New Zealand, it did not form part of the law until 1975, when the Treaty of Waitangi Act was signed, establishing a permanent Waitangi Tribunal to investigate breaches of the original treaty and make recommendations (without the power of enforcement) on claims brought by Māori. In 1999, to speed up the process for negotiating settlements associated with breaches of the treaty, the government changed the process so claimants could go directly to the Office of Treaty Settlements without engaging in the tribunal process. (Wikipedia) Nonetheless, the treaty is still celebrated on February 6th which is the annual Waitangi Day holiday.

Since one of my long-time photographic projects has been creating a comprehensive collection of honey bee images, I was delighted to find a few manuka blossoms (Leptospermum scoparium) still hanging on at the treaty grounds. They turned out to be the only floweringn examples I found in all New Zealand of this famous shrub, which produces the most expensive honey in the world). And best of all, there were honey bees nectaring on the blooms.

There was also harakeke or New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax), which has a starring role in Māori ethnobotany, its fibres having been used in traditional kākahu (cloaks), kete (containers) and whāriki (mats). Not to mention, of course, the popularity of its vibrant hybrids as colourful foliage plants in warmer parts of the world.

But we were at the Treaty Grounds to participate in an evening of traditional Maori activities: the enactment of a wero or warrior challenge as part of the pōwhiri welcome, then a musical concert by the performance group, followed by a traditional hangi dinner. We watched as our meal was prepared in the modern version of a pit oven, which would traditionally have been dug in the ground using heated stones to cook, instead of gas..

Under banana leaves, there were layered meats and fish, as well as kumara (sweet potatoes) and more. But it still had some cooking to do while we continued with our program….

…taking a walk through Waitangi’s beautiful bush to observe our own traditional ‘chieftain for a day’, Denver Botanic Garden’s Panayoti Kelaidis, engage in a traditional wero, or warrior challenge.

Another of our guests, Ciril, engaged in a further challenge in front of the Waitangi Treaty House. Fortunately, both Panayoti and Ciril passed the challenge and were welcomed; they then offered speeches of thanks to our Māori hosts. (And even the fact that you know the performers do this several times a week for hundreds of tourists doesn’t diminish the solemnity or the significance of the reenactments).

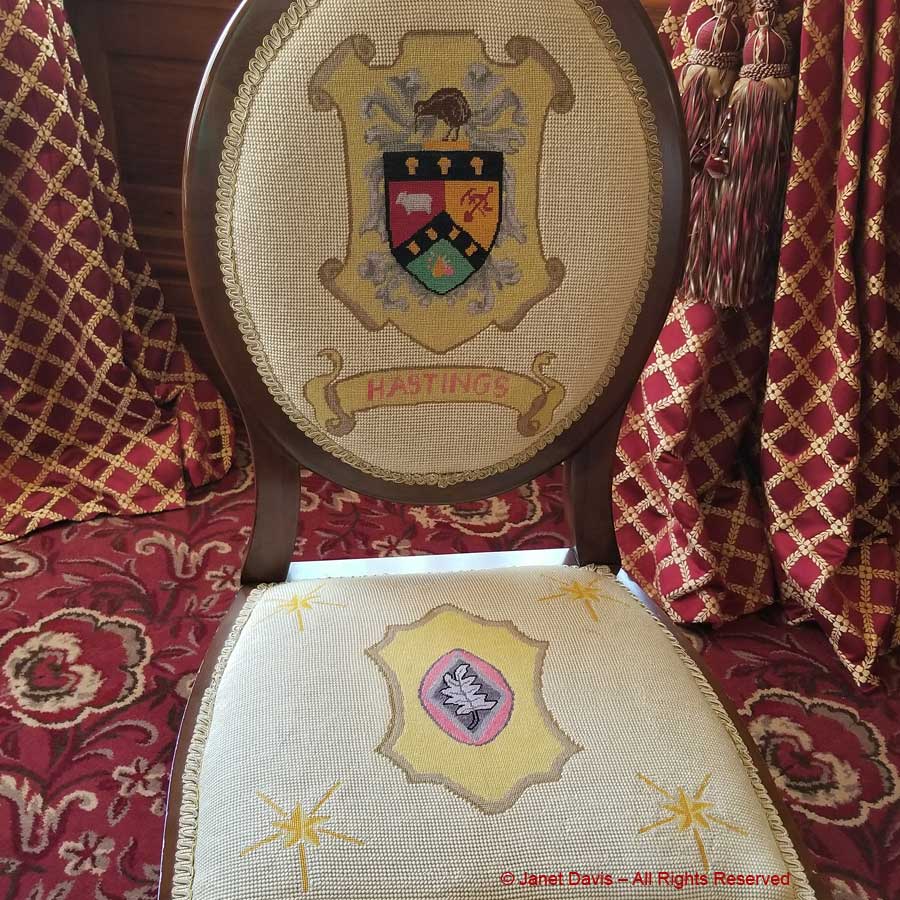

Although I didn’t visit the actual Treaty House, which was home from 1833-40 to James Busby, the first representative of the British Crown, we were welcomed into Te Whare Rūnanga (the House of Assembly), which was opened on February 6, 1940 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the treaty. Although similar in design to Kena Alexander’s wharenui, this building was intended to unite all Māori of Aotearoa and contains carvings and folklore from tribes throughout the country.

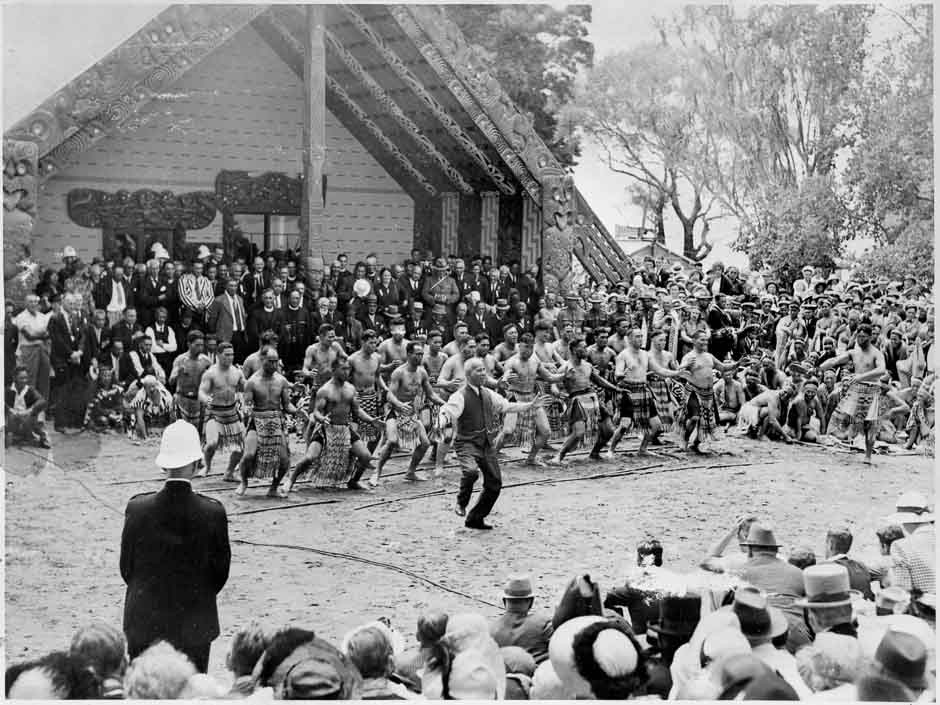

Below is a photo of Sir Āpirana Ngata, a longtime Labour politician (then retired) and organizer of the 1940 centennial, leading a haka. (And if you are unfamiliar with the spine-tingling Māori haka, you must watch the New Zealand All Blacks performing a haka before their 2011 World Cup rugby final against the French national team.)

Finally, it was time to enjoy a concert of traditional Māori music and dance, courtesy of the Te Pito Whenua performance group. What fun to have a front row seat to watch these talented artists with their beautiful tattoos….

…..and wonderful routines….

…. including the traditional Polynesian poi dance, featuring fancy acrobatic work with those poi balls.

As we departed the concert to enjoy the hangi buffet, Doug and I posed for a fun moment with the performers. As ‘touristy’ as it was, it also made me feel that the entire day — from the shores of Kerikeri Inlet to the kauri forest to Kena’s marae to this light moment on these historic grounds — had immensely enriched my understanding of and affection for this beautiful country, Aotearoa. Kia ora.