For a Canadian gardener in London in May to visit the Chelsea Garden Show (see my first and second blogs) and later the Chelsea Physic Garden and the Wildflower Moat at the Tower of London, it was a pleasure to climb out of our Uber on the far side of the Thames near the impressive gate of the Garden Museum. If it felt a little like attending a church service, that’s because the modern museum was constructed inside the deconsecrated Church of St. Mary at Lambeth. Although a church at the site was mentioned in William the Conqueror’s Domesday Book of 1086, it was erected in its present form in 1377, with the interior largely rebuilt in 1851. In 1638, when the famed plant hunter and gardener John Tradescant the Elder died, he was buried in the churchyard. In 1662, when his son John Tradescant the Younger died, his widow Hester arranged for an ornately-decorated tomb, which we’ll see later. Vice-Admiral William Bligh resided nearby on Lambeth Road; having lived through the 1789 mutiny on his ship HMS Bounty, he died in 1817 and his tomb is also here. Second World War bombs broke the 1888 altar donated by Sir Henry Doulton of Royal Doulton Ceramics fame and damaged the stained glass windows. Though an estimated 26,000 burials occupied the site, most were re-interred elsewhere when the dilapidated church was declared redundant in 1972, its riverside neighbourhood including historic Lambeth Palace, the London home of the Archbishop of Canterbury, then somewhat sad and derelict. Within 4 years, it was boarded-up and ready to be demolished.

Enter Rosemary and John Nicholson who visited in the 1970s to see the Tradescant’s gravestone and were shocked to see the church’s condition and what was about to happen. They founded the Tradescant Trust to develop a Museum of Garden History, opened in 1977, and save both the tombstone and the church. Between 2008 and 2017, the Museum underwent two stages of renovations to erect a sleek, modern infrastructure and mezzanine within the stone walls of the old church; to add a new gallery and café; and to develop gardens around its exteriors. It was also renamed The Garden Museum. The front garden near the entrance was designed by former architect-turned-garden-designer Christopher Bradley-Hole, while Dan Pearson was commissioned to create a garden in a courtyard occupied by a formal 1980 knot garden designed by Tradescant enthusiast and then-President of the Museum of Garden History, Lady Mollie Salisbury. But I knew little of the history as I wandered along the gravel paths among the tombstones in the front garden, where Bradley-Hole created lovely combinations of pale yellow-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium striatum) and Turkish sage (Phlomis russeliana), silver curry plant (Helichrysum italicum) and pink Madeira Island geranium (G. palmatum).

Parts of the front garden look almost wild, like this pretty combination of Serbian bellflower (Campanula poscharskyana)and Mexican fleabane (Erigeron karvinskianus).

Foxgloves (Digitalis purpurea) pop up here and there.

The churchyard provides an oasis of green in the neighbourhood, flanked by St. Mary’s Garden and a row of plane trees beyond the iron fence. More on that later.

Intriguing raised gardens hinted at the exhibition we would see in the museum.

Then it was inside to marvel at the way Dow Jones Architects transformed the church, the blonde wood, a cross-laminated timber product, matching the light stone.

I loved the way the ancient church architecture nestled seamlessly within the modern finishes.

This alabaster wall monument within the Pelham Chapel honours a young soldier – the fourth son of Francis Godolphin Pelham, Earl of Chichester and Rector of the parish 1884-94 – who died in France in the First World War.

Garden books for sale were displayed under wall monuments to 18th and 19th century clergymen. The gift displays featured painted lampshades and bases by ‘Bloomsbury Revisited’, artisans inspired by the work of the museum’s featured artists, including Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell.

Another gift display in the museum.

Museum displays are found throughout the building, including this reproduction Wardian Case, invented in the mid 1800s by Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward to create optimal conditions for the transport of plant collections on long ship voyages.

The permanent collection at the Garden Museum features artifacts related to all aspects of gardening, including this display of vintage seed packets.

“Gardeners at War” traces the history of government-mandated gardening initiatives through the Boer War, WWI and the “Dig for Victory” program of WWII.

I found the write-up on horticulturist Ellen Willmott, right, fascinating; it inspired me to look up her Wiki page which ended with: “Willmott’s prodigious spending during her lifetime caused financial difficulties in later life, forcing her to sell her French and Italian properties, and eventually her personal possessions. She became increasingly eccentric and paranoid: she booby-trapped her estate to deter thieves, and carried a revolver in her handbag.” Something to ponder the next time you gaze on that silvery giant sea holly, Eryngium giganteum ‘Miss Willmott’s Ghost’.

I adored this 1960 painting by the renowned society photographer/fashion designer Cecil Beaton titled “Cutting Garden Flowers”.

The first of these prints by prolific illustrator James Sowerby (1757-1822) looked so familiar – since I collect botanical prints of campanulas, including one from Sowerby’s Botany. He is buried nearby in Lambeth.

A spectacular juxtaposition of garden tools with a stained glass window.

Gertrude Jekyll’s c.1840 desk sits under her portrait.

Then it was into the temporary exhibit – a delightful collection of paintings, writings and artifacts titled “Gardening Bohemia: Bloomsbury Women Outdoors”, featuring Lady Ottoline Morrell, Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West. As the museum stated: “Ottoline Morrell described Garsington Manor as a kind of ‘theatre’ for social gatherings, and during the First World War she offered her home as a farm that would provide employment for conscientious objectors and pacifists”. Artists and writers who visited Garsington including Dora Carrington, Mark Gertler and John Nash had work in this exhibit.

Vanessa Bell was Virginia Woolf’s sister. She and her lover, artist Duncan Grant, renovated a wild garden at a Sussex farmhouse called Charleston, which would become their outdoor studio. As the Charleston website says: “Charleston became the country home of the Bloomsbury group, with artists, writers and intellectuals making regular visits to the rural home in Sussex. Bell and Grant’s domestic and creative partnership would endure for 50 years, and, although Grant’s sexual relationships were generally with men, they had a child, Angelica, together in 1918. Despite their close partnership, Bell and Grant maintained creative and romantic connections with other people…”

Virginia Woolf and her husband Leonard moved to Monk’s House, a 16th century cottage overlooking the Sussex Downs, after the First World War; she would remain here until her suicide in 1941. Near the garden they built, she had a writing lodge where, according to the exhibit signage: “she infused her prose with the sensory intensity and mysterious life of the natural life surrounding her, interwoven with gardens from her memory and imagination.” Monk’s House would be a place of retreat from the London world of Bloomsbury and solace for Virginia in her times of severe depression.

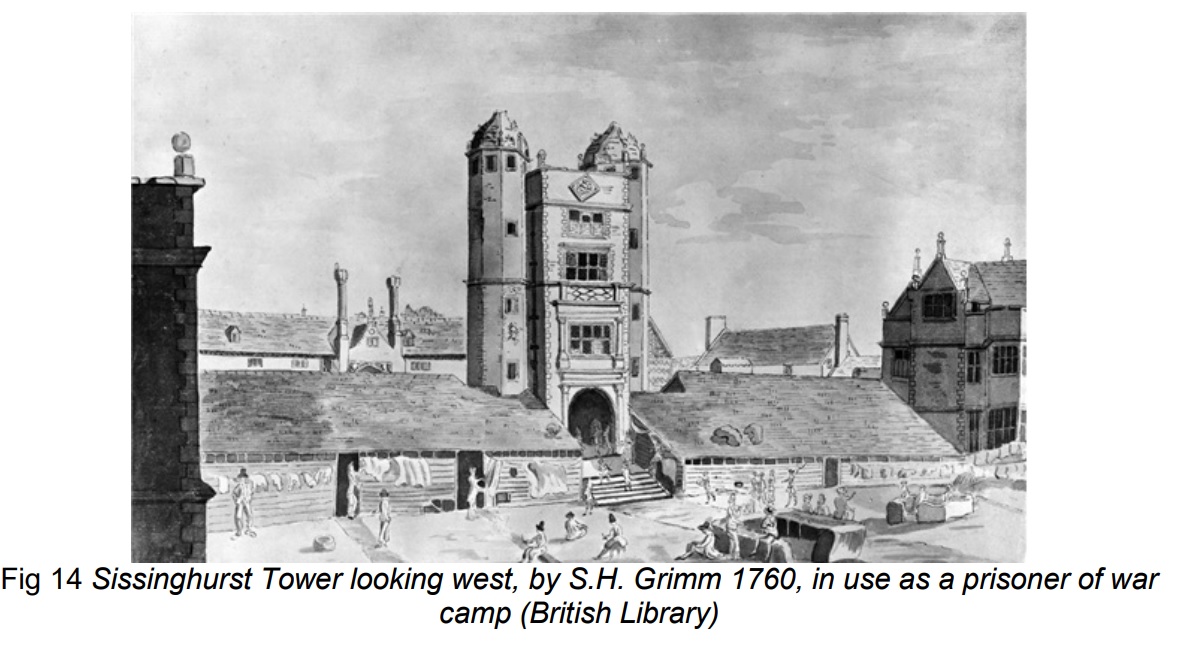

I was fortunate to visit Sissinghurst for the second time in 2023 and wrote a blog then about the garden and Vita Sackville-West called “Sissinghurst in Vita’s ‘Sweet June’”, so it was a pleasure to see in living colour the 1918 painting of her by William Strang. This part of the exhibit included photo albums and some of Vita’s journals including….

….. this one, noting changes she wanted made to her garden with its dark rosemary hedge which could be improved by removing the santolina and replacing with a foreground planting of orange roses, Iceland poppies and tiger lilies.

We were looking forward to going outdoors to the new garden but stopped to watch a little video. The segment with Ken Ralph of Canewdon, shown below, was particularly poignant – since Ken is a tradescantia breeder and he aimed to create a “Chelsea standard” tradescantia for the reopening of the Garden Museum, whose development began with a visit to the Tradescant family tomb and creation of the Tradescant Trust.

Then we went downstairs and out into the new courtyard garden with its funerary muse, the Tradescant chest tomb. An 1853 replacement of the 1773 replacement for Hester Tradescant’s original 1662 commission for her husband, botanist and plant collector John Tradescant the Younger (1608-62), it also commemorates his father, the great plant collector John Tradescant the Elder (1570-1638), his wife Jane, his daughter-in-law Hester and his grandson John. It is ornately carved with references to nature reflecting The Ark, their family museum, now recalled in a gallery of the same name in the Garden Museum. Wrote Owen Moore in a 2017 article in The Guardian: “In the Ark, the cabinet of curiosities that they created by their home in Lambeth, south London – and which became the basis of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford – they brought together the natural, the artificial and the supernatural: carvings on cherry stones, seashells, the cradle of Henry VI, a stuffed crocodile, religious objects, talismans. This was more than whimsical mixology: it was a view of the world based on the connectedness of things.” There is much more information on the Tradescants and their 17th century museum nearby on this blog.

Backing up a little, we now see the Tradescant tomb at the edge of the courtyard garden created by Dan Pearson for the museum’s reopening in 2017. Surrounding it are new pavilions, their walls clad in bronze tiles, separated by a cloister. One pavilion hosts the garden’s lovely café, whose seating extends out into the garden.

In 2023, I visited Hillside, the Somerset garden Dan Pearson shares with his partner Huw Morgan and wrote a blog about that delightful day. Here at the Garden Museum, as he wrote in Nov. 2018 in his newsletter Dig Delve, he looked initially at abstracting Lady Salisbury’s knot garden, but decided instead with his usual brio to invoke the plant collectors’ memory: “With the exploits of the Tradescants as inspiration, it was a small step to imagine this courtyard as a giant Wardian case – an aquarium-like structure invented in the 19th century to transport exotic and delicate new plant discoveries long distances by sea in a protected environment. The glassy cloister, our metaphorical Wardian case, allowed us to present a garden of curiosities and treasures.”

In the centre of the courtyard garden is the 1817 tombstone of Vice-Admiral William Bligh, who lived at 100 Lambeth Road a few blocks from the church. Having survived the 1789 mutiny on his ship HMS Bounty in the South Pacific in which he and 19 loyal crew members were set adrift in the ship’s open launch, he sailed 3,500 nautical miles, with stops enroute in Tonga and Australia, to the Dutch colony of Timor where passage back to England was arranged. To the left of the tombstone is honey bush (Melianthus major), to the right is a schefflera from plant hunter Bleddyn Wynn-Jones at Crûg Farms Nursery and Nandina domestica with its red berries.

I liked this dramatic pairing of autumn fern (Dryopteris erythrosora) and Geranium macrorrhizum ‘White Ness’.

The big palmate leaves of rice paper plant (Tetrapanax papyrifer ‘Rex’) frame the stained glass window of the church.

Then it was time for lunch. We had no reservation (highly advised) but were seated quickly. The menu was varied but my choices were absolutely delicious: an asparagus-goat cheese tart and butter lettuce salad with rosemary focaccia and a glass of white.

As we left the Garden Museum, we stopped at some signs inside describing the current initiative to create a garden complex outside the churchyard. “We have restored the church and made a garden and now we want to make Lambeth Green again.”

Lambeth Green is the next step in this community revitalization.

Walking out of the museum, we strolled along the path of St. Mary’s Garden adjacent to the churchyard. This is a lovely, public community space. You can see the Lambeth Bridge over the Thames in the distance. When Lambeth Green goes ahead, it will incorporate and transform this space and a reconfigured traffic roundabout.

And we took a final glance back through the foxgloves and euphorbia at the old church, looking the same on the outside but wearing its shiny new museum clothes on the inside.