On this Easter weekend of this exceedingly strange and sad spring, I give thanks for a joyous bouquet of pale pink outside my kitchen window and the comfort its dependable, early spring appearance offers. I first wrote about this shrub almost 30 years ago, in a column I had in a little community newspaper called Toronto Gardens. I later reprised it for my old website, but I decided it needed another nod of thanks here. Here is what I wrote in the early 1990s, after a mild winter, about Farrer’s viburnum (Viburnum farreri).

Record-breaking December and January temperatures in the northeast have resulted in one of my favourite shrubs putting on a winter flowering show. Not that Farrer’s viburnum (Viburnum farreri) ever waits beyond late March or early April to open its tight pink buds. But this winter, it broke dormancy well before Christmas and has been in bloom ever since, even with the mercury dipping to –16C (3F) one night. Prolonged frigid spells keep the pink buds just closed, but even one day of warm sunshine will nudge many into full flower. In fact, last week, I cut a few small branches and placed them in a bud vase so I could enjoy the sweet-scented flower clusters at my desk. But the warm indoor temperatures meant the blossoms lasted only a day or so before dropping, for this is one plant that truly thrives in the cold.

Given that I no longer “thrive in the cold” myself, it is such a treat to enjoy a shrub that does. This week, night temperatures are forecast to dip below freezing, but that won’t bother this shrub. Even on December 22nd, 2013, when I photographed the buds encased in ice that had fallen from the sky the night before, throwing Toronto into a multi-day power failure and bringing tree limbs crashing down all around the city, it still flowered months later.

Some years, it suffers snow just as its dark pink buds are plumping up, as happened below on March 9th, 2012.

Truth be told, it’s not the most shapely of shrubs. This is how I found it at Mount Pleasant Cemetery on March 30, 2010, another early spring, just as the first inflorescences were opening on naked twigs.

But I can forgive its shape when it is literally covered with palest pink blossoms as the first leaves emerge, as it was here in my garden with forsythia in my neighbour’s garden behind it on May 7, 2019.

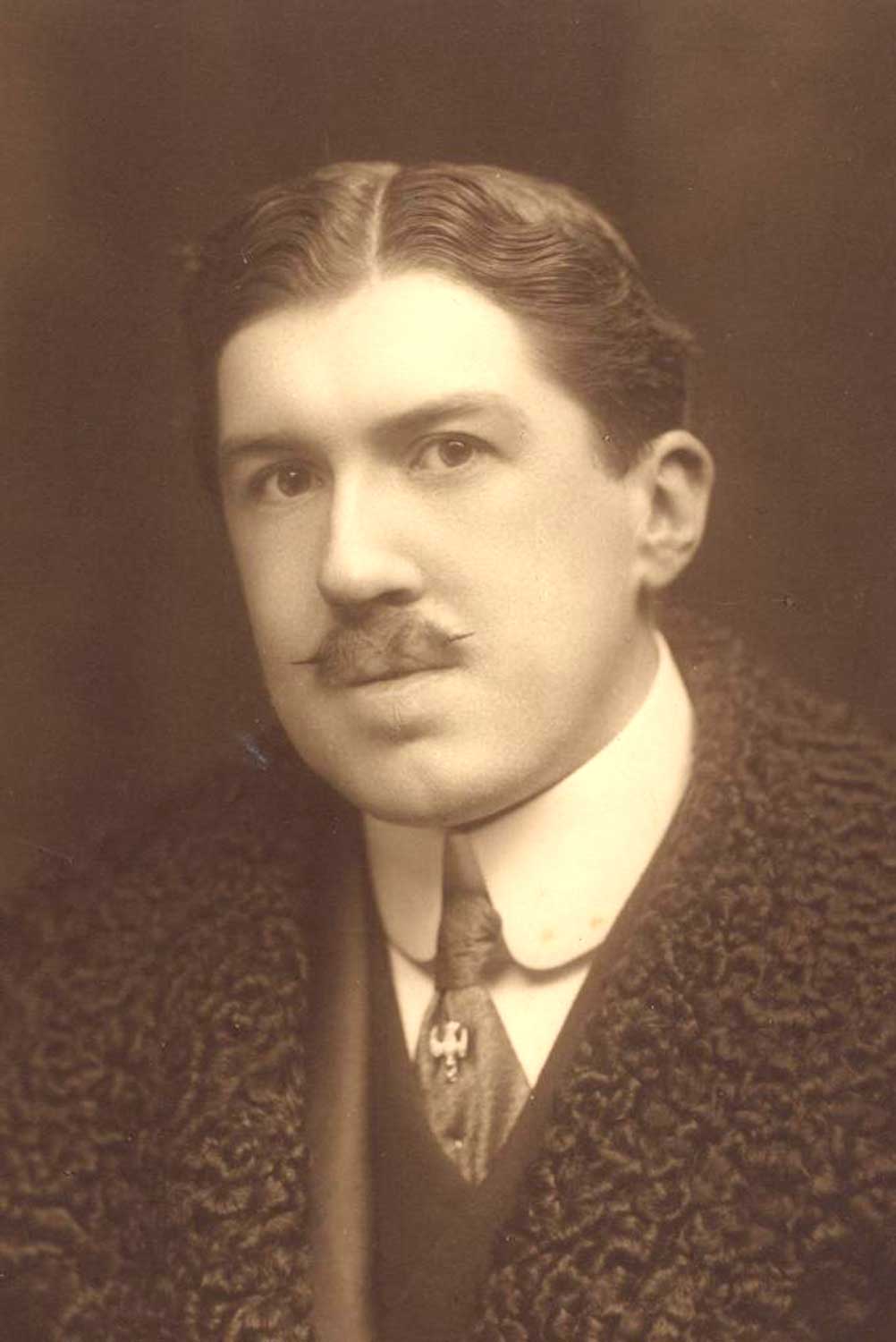

The history of Farrer’s viburnum is colourful. In 1914-15, British plant explorers Reginald Farrer, below, and William Purdom were prowling the foothills of the northern mountains separating China from the Mongolia border, collecting seeds of new species. Although the shrub was a favourite Chinese garden plant at the time, growing at very high altitudes, its “discovery” in the wild is credited to Farrer. Writes Alice Coats in her book Garden Shrubs and Their Histories. “He sent home abundant seed and would have sent more, but for an unfortunate falling-out with his Highness Yang Tusa, Prince of Jo-ni, who…in a fit of pique, set to and sedulously ate up all the Viburnum fruits in his palace garden, and threw away the seed.”

Originally called Viburnum fragrans to mark its sweet perfume, it was renamed in Farrer’s honour. Today, fragrant viburnum is considered a winter-flowering shrub in the Pacific Northwest and in Britain, where its flowers might open on a mild day in late autumn with flowering occurring sporadically until April. It likes full sun and reasonably good soil, but can’t be called a fussy shrub. Despite its tendency to early bloom, it is root-hardy only to USDA Zone 5a – Canadian Zone 6B, and benefits from some protection from harsh winds and winter sun. It reaches 2.5 – 3 metres (8 – 10 feet) at maturity with almost as large a spread. The flower clusters start out pale pink and fade to white and are quite modest in size — more like the Burkwood viburnum than the big snowball blossoms of the fragrant snowball Viburnum x carlcephalum. For small gardens or for low hedging, there’s a very good dwarf form called ‘Nanum’, which reaches about 1 metre (3 feet). There is also a white form, V. farreri ‘Album’, below.

Farrer’s viburnum was crossed with Viburnum grandiflorum at Bodnant Garden in Wales to give us Viburnum x bodnantense. This hybrid is usually seen as the cultivar ‘Dawn’, a lovely shrub whose flowers are rosier pink than Farrer’s.

Both Farrer’s and Bodnant viburnums are favourites of pollinating insects, given how early they flower. One year I found a bumble bee queen taking nectar on ‘Dawn’, below.

But more often than not, it’s better insect-watching in my own garden with Viburnum farreri. Below is the mourning cloak butterfly, which overwinters in Toronto and needs nectar as early as possible. This was April 16, 2017.

That same week, I found a red admiral butterfly on the flowers. Obviously, it needs to be above a certain temperature for insects to thermo-regulate, and that has been difficult this cold spring.

In 2012, one of the earliest springs I can recall in Toronto, we had a celebratory dinner on our sundeck on March 19, 2012 with little sprigs of Farrer’s in a cylindrical vase.

But it’s the perfume of those humble flowers that I adore, and that doesn’t necessarily transfer to the Bodnant hybrid. I read the following paean to its fragrance on a website, attributed to British garden writer Mark Griffiths: “We mustn’t let the bodnantense hybrids supplant their parent; V. farreri is twiggier and more crabbed and its flowers are smaller tighter and paler, but there’s far greater poetry in its looks and purity in its fragrance. Its perfume, to my nose, is more hyacinths and almond essence than heliotrope. On a drab winter’s day, its effect is magical in the garden and even stronger in a room, whether from a few cut twigs or a pot-grown plant brought indoors for winter. This scent seems less like reckless extravagance thrown away on the chill, bee-free breeze once one realises that V. farreri doesn’t behave with us as it does in its native China. There, it holds back all through the months of harsh cold and drought, not blooming until spring, whereupon it faces stiff competition for pollinators from other blossoms. Its alluring fragrance is prudent, not prodigal. Our winters are mild and wet by comparison and this encourages it to flower in fits and flushes from late autumn onwards.”

Toronto winters are more like China than England, I expect, so I appreciated what Helen Van Pelt Wilson and Léonie Bell wrote about Farrer’s, which they called the fragrant guelder, Viburnum fragrans, in their 1967 classic The Fragrant Year: “The fragrant guelder…has long been a favorite shrub, its perfume mysteriously combining the scents of wisteria and clove in the manner of certain lilacs. Unlike the familiar V. carlesii , which gives at best only ten days of bloom, V. fragrans flowers modestly for weeks on end. Even after our harshest winters, all the rose-red buds open to rich pink flowers that grow paler with age.”

I shall leave you with a little Easter nosegay. It’s on my kitchen table now. A few wisteria-clove-hyacinth-almond-scented sprigs of Reginald Farrer’s lovely Chinese shrub, along with the little striped, ice-blue Puschkinia scilloides and Corydalis solida ‘George Baker’. Aren’t we lucky that his Highness Yang Tusa, Prince of Jo-ni didn’t eat ALL of the seeds?