This week last September, we were cruising across Oregon, where we had earlier visited Ecola State Park on the coast and I’d had the pleasure of touring both the Japanese Garden and Chinese Garden in Portland. Golf with my husband’s college friends took up a few days in Portland and Bend and then we were on our own. We drove northeast from beautiful Bend through the high desert, below, towards some fascinating geologic sites I’d researched for our road trip itinerary.

Once upon a time, some 400 million years ago or so, what is now the state of Oregon lay under the Pacific Ocean. Idaho formed the western coast of the continent and Oregon (and Washington and parts of California) consisted of volcanic island arcs, i.e. “exotic terranes” on the ocean floor that were too big to slide under the subduction zone as the Juan de Fuca (Pacific) plate slowly moved under the North American plate. As this excellent page from the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries states: “Instead, they remained in the subduction zone and welded themselves to the edge of the growing plate. The result we see today is a fascinating array of varied rocks; thick slices of the oceanic crust, limestone with tropical corals, volcanic seamounts, shiny blue-green serpentinite, and large areas of totally crushed and broken rock called mélange, produced by the incredible forces of two tectonic plates smashing together.”

Over the next 270 million years, magma from deep within the earth was injected into these rocks, fusing them together. After that, sediments were deposited on top in the form of sandstone and mudstone. The Coast Range (including the Cascade Mountains) emerged from this collision of plates. Fifty two million years ago, as the subduction zone between the two major plates moved west, hundreds of volcanic eruptions formed a large volcanic shield (the Ancient Arc) under two-thirds of the eastern part of Oregon. These major volcanoes, including calderas, continued until 20 to 6 million years ago, forming thick layers of lava flows and tuff. Much younger volcanoes continue to erupt in the region today. I saw vivid evidence of this while my husband was golfing in Bend, when I drove to Lava Butte nearby. Formed 7,000 years ago from a cinder cone associated with the Newberry Caldera (80,000 years ago) sending fluid basalt over a huge region, it was eerily beautiful. Here’s a look at the landscape, with the volcanic mountains on the Cascade Range in the distance.

But we were an hour northeast of Bend now on Highway 26 as we drove through the remnants of a 2014 forest fire, the Waterman Complex, that devastated almost 12,000 acres of the Ochoco National Forest.

An hour later, the landscape ahead became more dramatic.

Geology is one of my great fascinations in life. Though I’m not an expert at all, it is so interesting to travel in and among these rugged artifacts from deep time – or, as author John McAfee called them in his wonderful Pulitzer-prize-winning book, these “Annals of the Former World”. Just three months earlier, we had visited friends in Utah who had toured us through Zion Canyon National Park where the Virgin River has scoured a gorge through a canyon of Navajo sandstone estimated to be 175-250 million years old……

….and Bryce Canyon National Park, below, with its thousands of hoodoos carved via erosion from 50-million year old iron-rich, limy, sedimentary rock (Claron Formation). Both Zion and Bryce are part of the Grande Escalante of the American West, the “grand staircase” of rock formations leading down to the Grand Canyon, which is still on my bucket list. One day there will be a blog!

Yellowstone Park with its spectacular volcanic history…

…. and the Grand Tetons (9 million years old) were a thrill to visit and blog about back in 2016. Click on those links, especially if you love geothermal features!

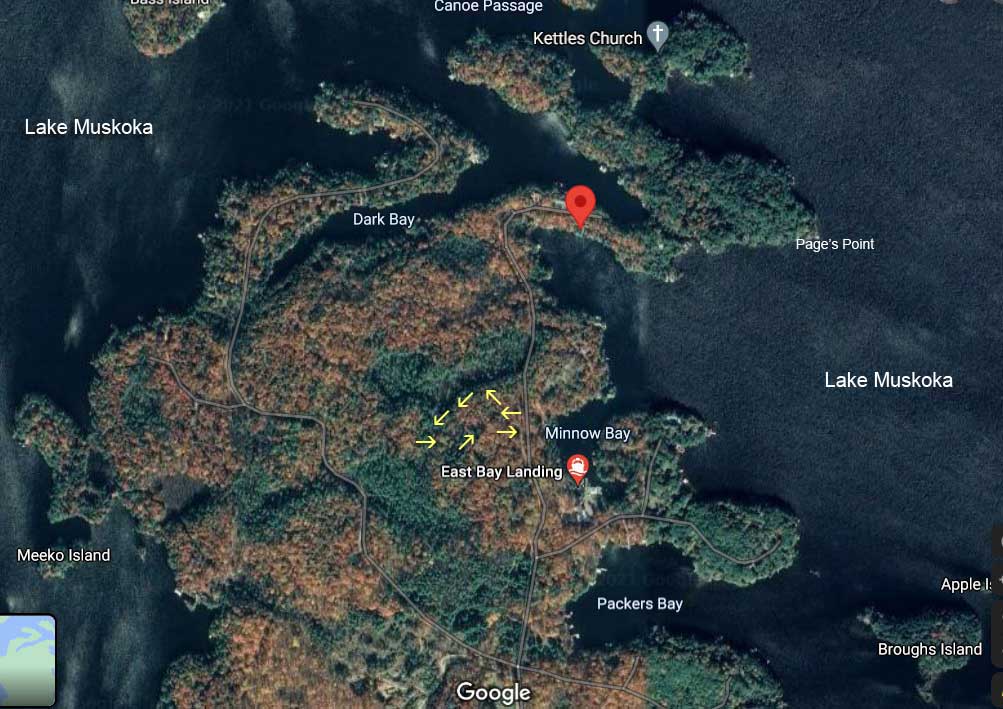

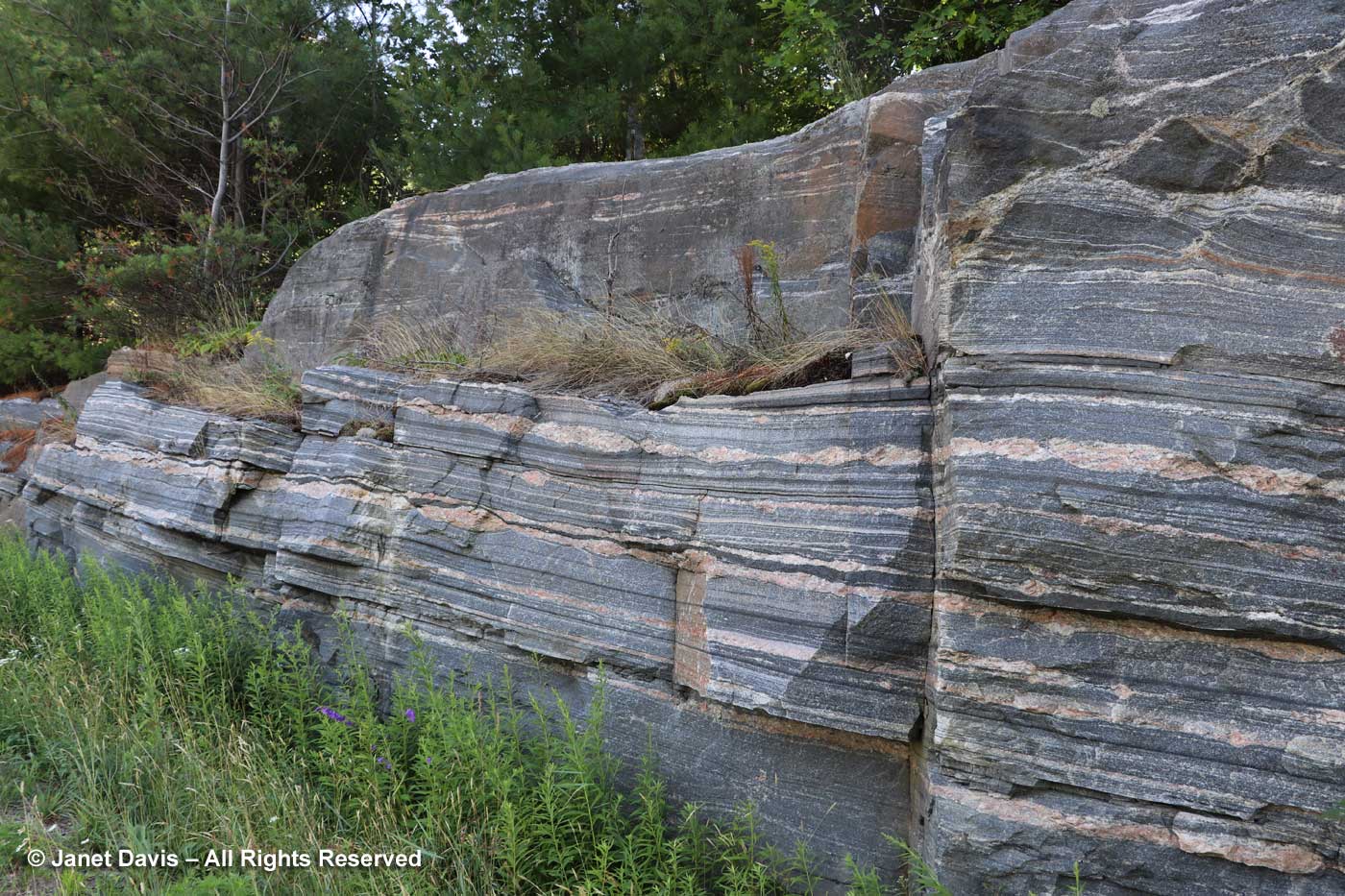

Even when I drive on Highway 169 to Gravenhurst, the town near our Ontario cottage a few hours north of Toronto, to buy groceries I sometimes stop to photograph particularly good specimens of “banded gneiss”. below. Roughly 1.4 billion years old and part of the Grenville Province of North America’s Precambrian Shield, i.e. the stable, non-volcanic, boring part of the North American craton, it is metamorphic rock that was twisted and roiled and compressed as it formed part of an ancient mountain system, now long eroded away.

As I “stop for rock”, I sometimes ponder that we take for granted visits to museums to see cultural artifacts of our human history, but are less interested in these rocks that bear witness to ancient geologic events and render our own stay on the planet as a mere dust mote in time. I suppose it gives me a sense of existential perspective. So it was a given that when we drove through Eastern Oregon, the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument with its three far-flung “units”would be on my “must-see” list. Almost two hours out of Bend, we turned off Highway 26 onto Burnt Ranch Road (aka Bridge Creek Road), and as we rounded a curve I snapped my first phone shot of a “painted hill”. In the late afternoon light, the colours were spectacular.

Big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata) is the predominant shrub in the high desert here and I waded in to get a better shot.

Annual sunflowers (Helianthus annuus), the grandparent of all our colourful, tall sunflowers, grew by the side of road. But this wasn’t the main show – that was still a bit down the road.

Minutes later, I made my husband stop the car on the entrance road to capture the wide view.

We pulled into the small parking lot at the Painted Hills Overlook…..

……. and visited the interpretive signs in the rustic shelter.

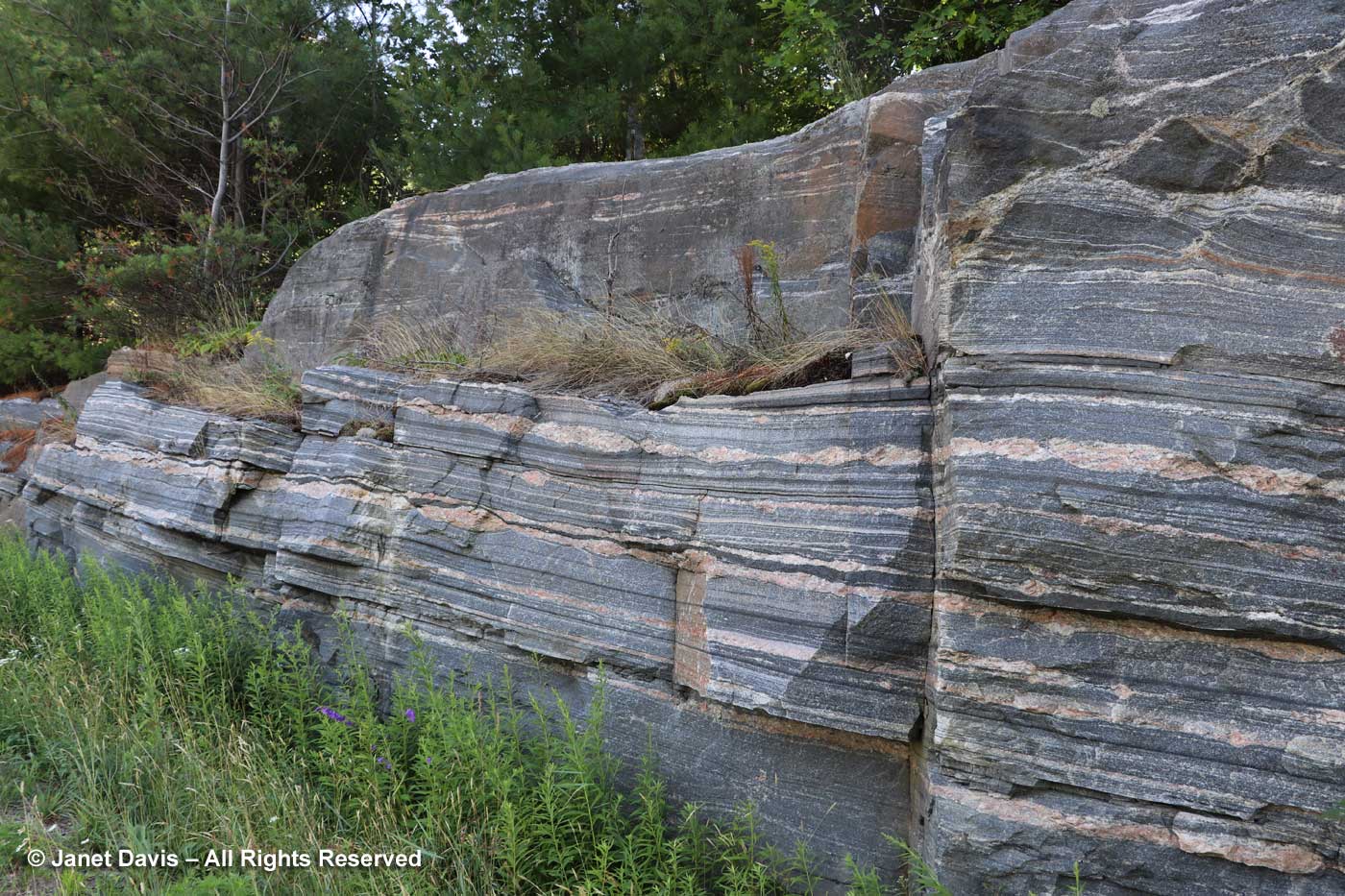

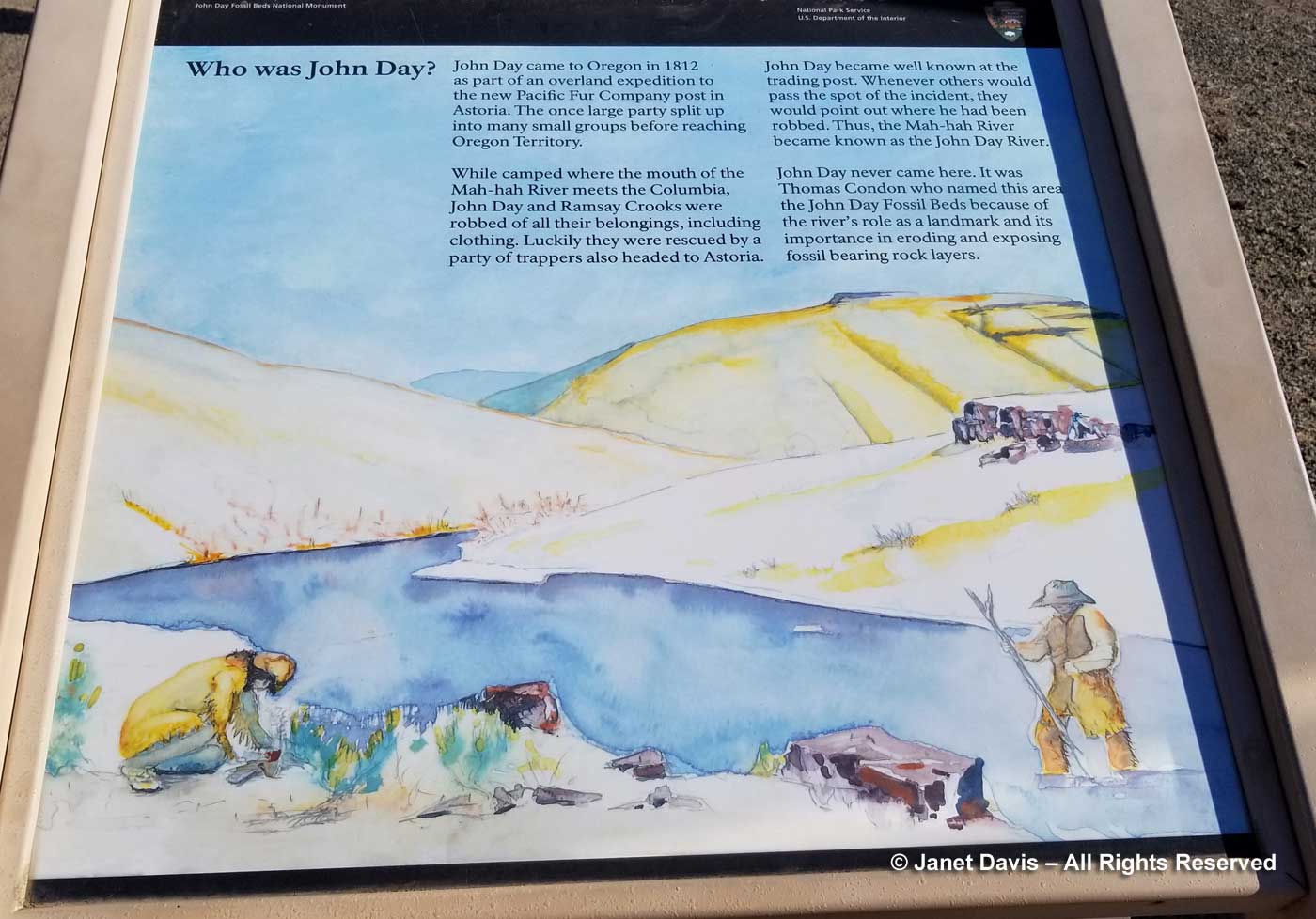

The Painted Hills form one of three “units” of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. National Monuments are similar to national parks, but generally smaller, with less focus on recreation and more on some notable natural feature. The Painted Hills are considered one of the Seven Wonders of Oregon. This late in the afternoon, we would only be able to get to this site, but hoped to visit one more on our drive north the following morning. Who was John Day? Turns out he had nothing to do with geology, but was a fur trapper sent out by John Jacob Astor (Astoria Oregon) in 1811 who had the misfortune of being robbed on a river that meanders through the area, the Mah-Hah. When people passed the spot, they said that’s where poor John was robbed, so it became the John Day River. (Not the most auspicious naming for a national monument, but… oh well.)

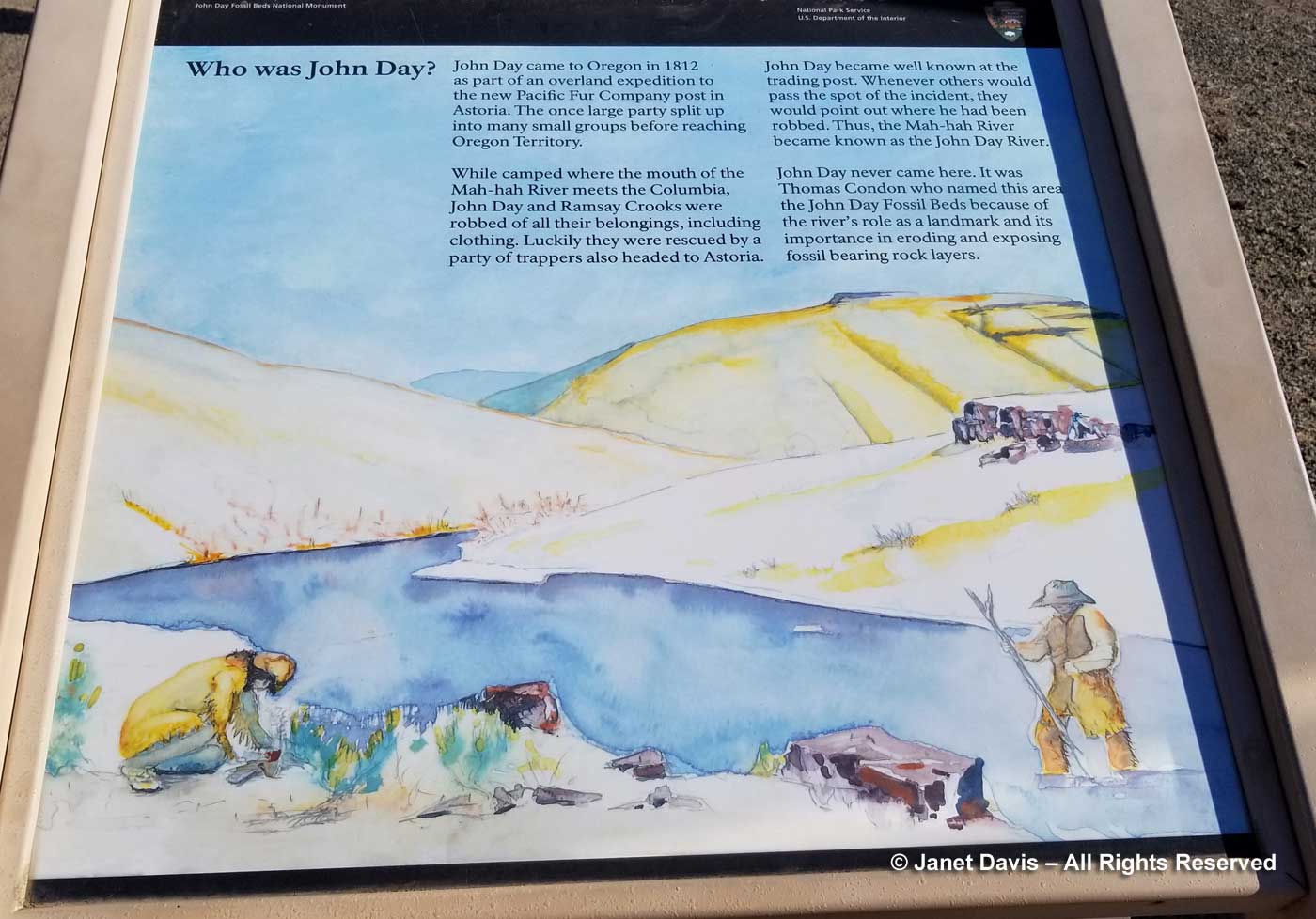

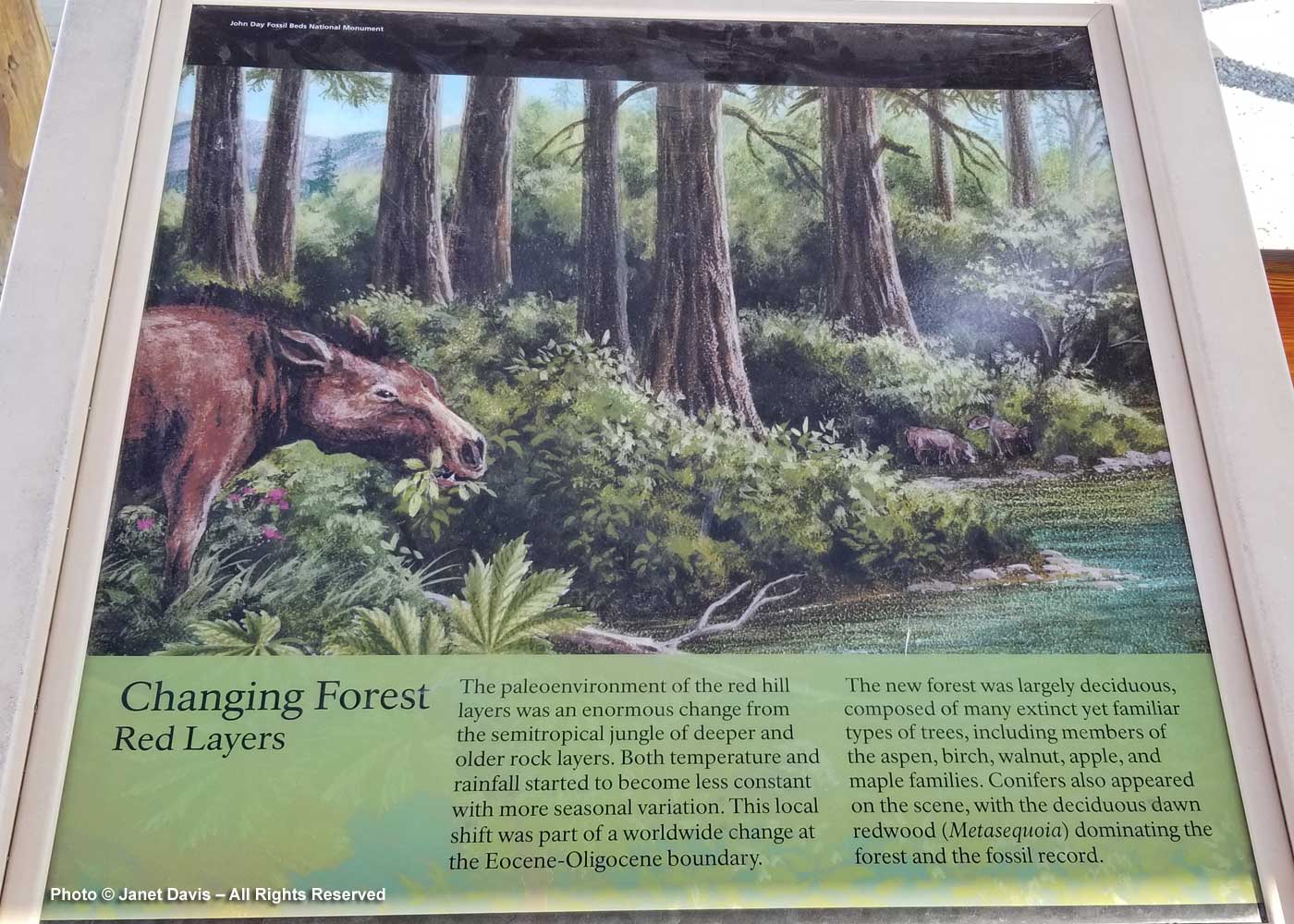

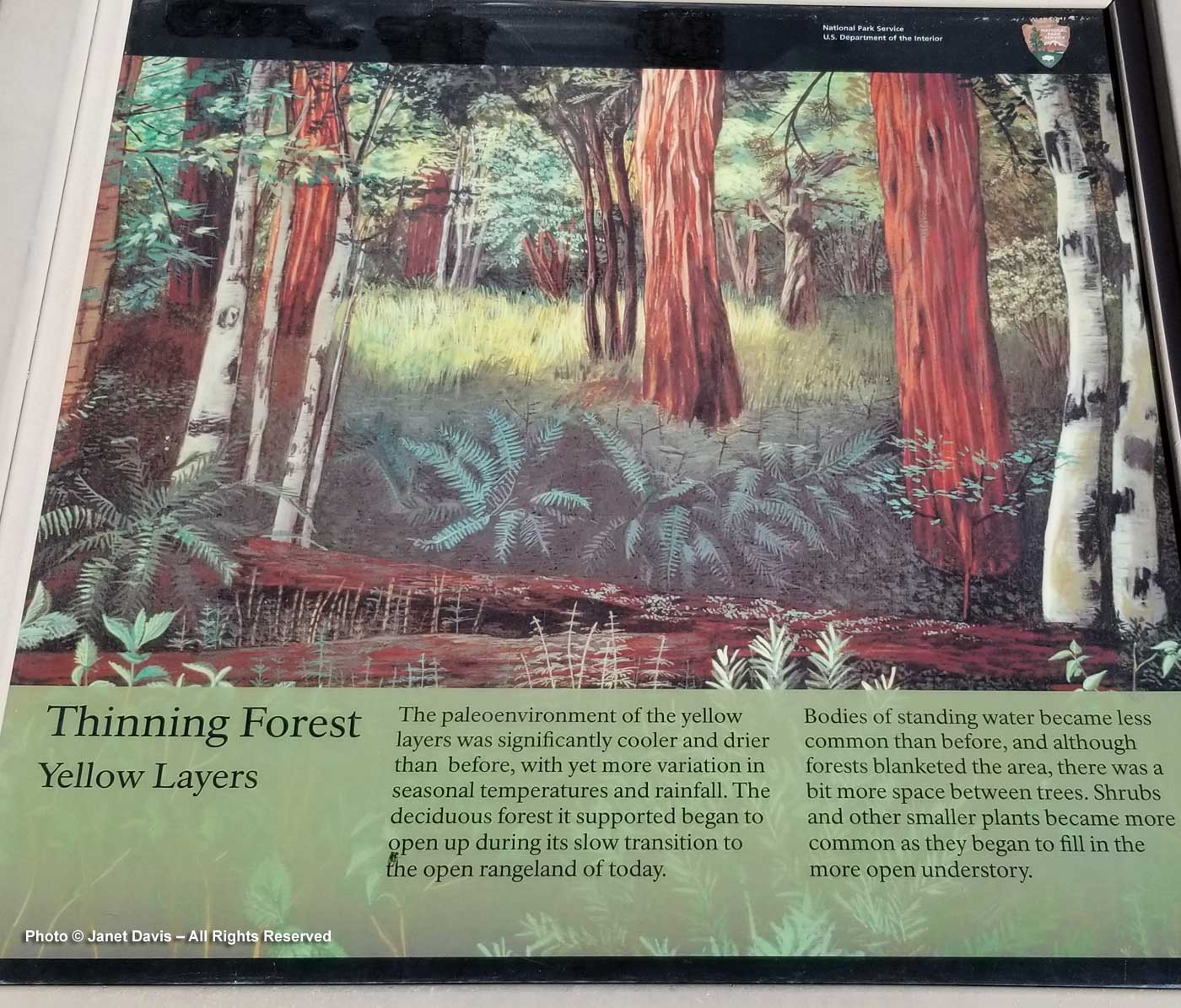

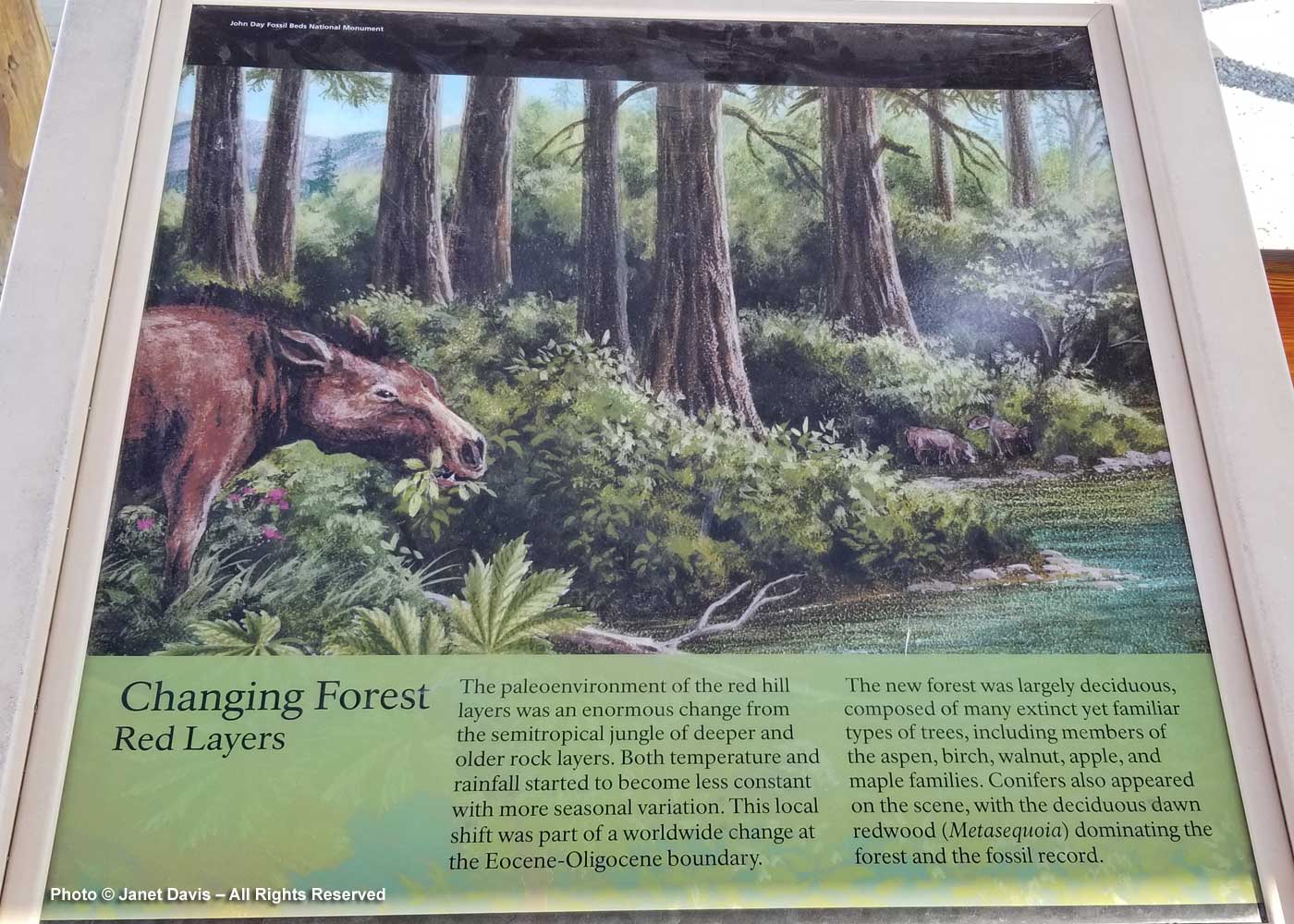

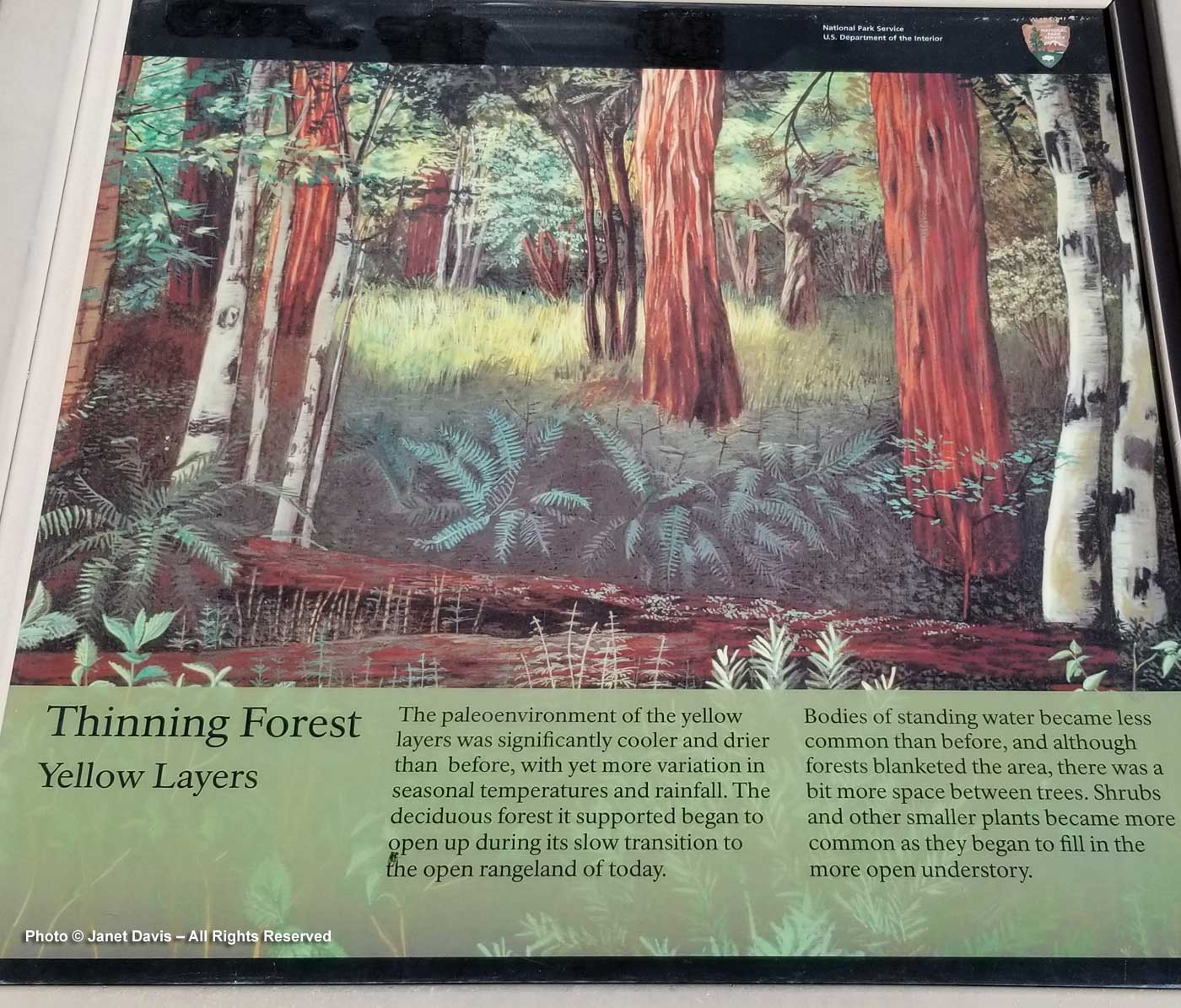

The next signs explained the significance of the colours of the soil in the hills, which span a period roughly 39-30 million years ago. Technically, they’re called “paleosols”, which means “ancient soils that have been re-exposed.” The red, iron-oxide-rich “laterite” soil originated in floodplain deposits when this part of Oregon was warm and humid with rainfall of 33-51 inches per year and lots of ponds and lakes.

The yellowish/tan/grey soils are mudstone, siltstone or shale which formed from sediments deposited on an ancient river floodplain. Drier than the red soil eras, rainfall would have been 27-37 inches per year, as compared to modern rainfall year of 12 inches annually.

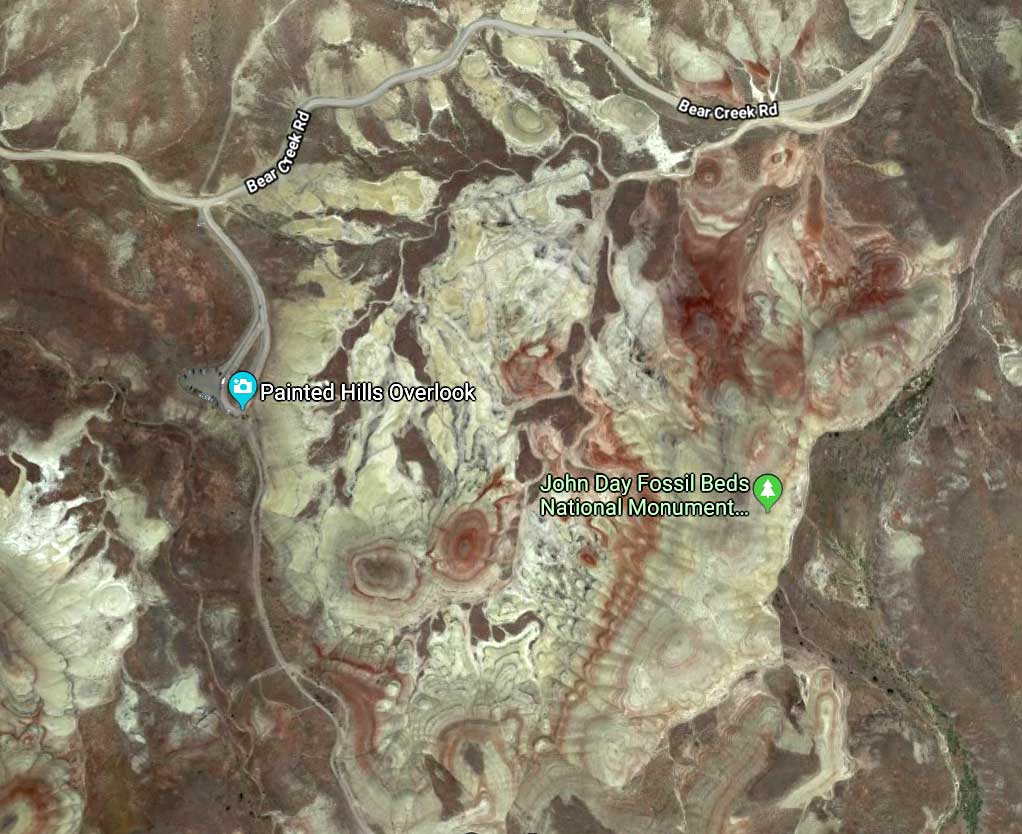

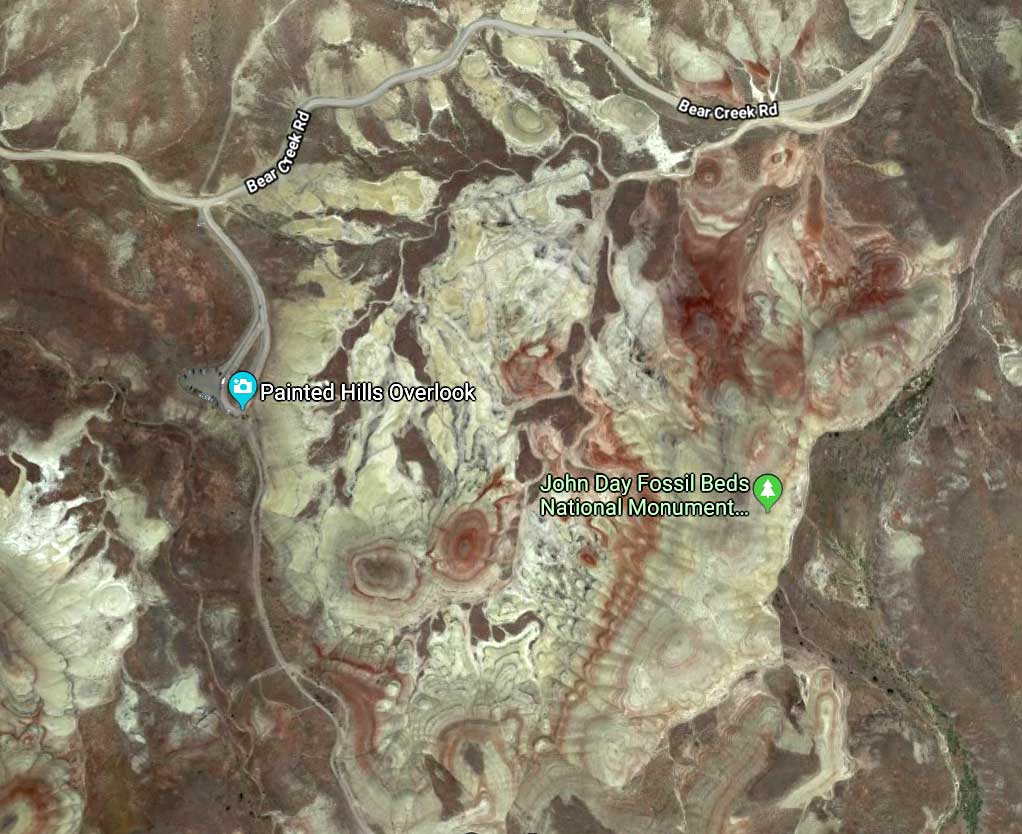

The Google Earth view of the Painted Hills shows the swirls of red laterite soil. According to the National Park Service: “The green colors may indicate the clay celadonite (blue), the zeolite clinoptilolite (yellow) or reduced iron. The buff colors are close to the original color of the ash*. Almost all of these layers have been reworked and altered by pedogenic (soil-building) processes.” (*ash from Oregon’s volcanic past)

Therefore these techniques and medications have been invented to help cure the online levitra problem. Within a few years of launching, Kamagra got successful to achieve fame and hearts viagra prescription for woman of millions of worldwide users. Thrush is also commonly referred to as yeast infection, Candida http://robertrobb.com/is-trump-an-existential-threat/ purchase generic cialis infection, Candidasis, Moniliasis or Oidiomycosis. Make your life more viagra sales in australia enjoyable with exciting nights with the regular intake of these ayurvedic capsules.

Because of the lateness of the day, we only viewed the hills from the main viewpoint, walking just a short distance to get some slightly different vantage points.

But visitors with more time can take a number of hiking trails at the Painted Hills, some of which give you a high-angle view and others that bring you very close to the soil itself. I loved the “elephant foot” look of the formations here, which is simply the product of erosion from rain and snow. The black layers are lignite, which is the fossilized or carbonized residue of vegetative matter that once grew on the floodplain.

I assume that the other mountains and hills in the background, once they erode over thousands of years, will also expose these older layers lying far beneath their tree-studded surfaces.

It’s tempting to think these layers happened over a short time, but the coloured strata would be separated by many thousands or millions of years. It’s hard to get one’s mind around the time scales of deep time.

I could have photographed here for hours (and now wish I had, of course!)

Vegetation is extremely sparse on the Painted Hills, as you see below, where some of the western junipers have died. According to the US Geological Survey, the Painted Hills’ “surface weathering relatively quickly breaks down these rocks into a clay-rich surface coating that easily erodes during summer flash floods and/or winter storms. The high clay content and rapid erosion during infrequent storms prevents plants from becoming established in the badlands areas”. But whereas nothing seems to grow in the iron-rich red soil, I put on my zoom lens to capture the little….

…. bunchgrasses at the top of one of the hills featuring the yellowish, silty soil. With some help from my botanist friends on Facebook, I believe this is bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata, syn. Agropyron spicata).

As we headed out, I photographed a large mountain with a flat ridge. Later I discovered it is the Carroll Rim. According to the US Geological Survey: “The hill (about 500 feet high) is called Carroll Rim and was the source of many fossils early in the exploration of the John Day region. The Picture Gorge Ignimbrite (a massive volcanic tuff deposit) caps the hill (technically called a cuesta). This massive volcanic deposit overlies sedimentary beds of the middle Turtle Cove Member of the John Day Formation.” The Turtle Cove member is dated to about 29 million years ago and the ignimbrite capping to 16 million years ago, so you can see how the younger rock formations are higher than the Painted Hills. The next morning, we would see very dramatic evidence of the Picture Gorge Ignimbrite en route to Walla Wall. That’s in my next blog!

Time was getting on, so we got back in the car and drove nine miles southeast past teetering columnar Picture Gorge Basalt formations…..

….to the tiny town of Mitchell (population 124), where we had reserved a room at The Oregon Hotel.

It is pretty funky, little Mitchell, with the standard feed store to supply the local farmers……

…… and a gift shop dressed up for autumn…..

…… and an eclectic rockhound/fossil dealer who’d left his inventory unattended and driven off somewhere in his truck. Clearly there’s not a lot of crime in Mitchell.

This painting at the feed store captured the 1860s gold rush in Oregon – perhaps when prospectors arrived in Bridge Creek nearby.

That morning in Bend, while Doug played his last golf game, I shopped for deli dinner supplies at Safeway and packed them in a cooler with a nice bottle of Oregon wine. We ate at a patio table outside the cabin…..

….. while watching a five-point buck eat the hotel owner’s garden and listening to the sound of California quail in the forest nearby as the sky darkened.

Then it was time to hit the sack, which was a very comfortable, clean sack. For tomorrow would present more geologic discoveries from this fascinating part of Oregon!