One of the best things about travelling for me is visiting gardens. And one of the best things about having pals who are gardeners is the chance to visit beautiful private gardens at the drop of a hat! So it was that the day after our spectacular May visit to Garden in the Woods in Framingham, MA (see my 2-part blog beginning here), my dear friend Kim Cutler of Worcester MA and Doug and I found ourselves walking up the stone path in front of the pretty yellow house of Kim’s friends, Shirley and Peter Williams at Brigham Hill Farm in North Grafton, MA. The oldest part of the house dates from approximately 1795 and the property is on land established by Charles Brigham in 1727. According to the Grafton Land Trust, “Charles Brigham was one of the ‘Forty Proprietors’ who were given the grant to settle Grafton by King George II of England. The farm eventually covered most of Brigham Hill and raised fine dairy cows.”

Though Shirley was entertaining a friend in her lovely screened porch….

…. she cheerfully invited us to tour around the property ourselves.

What a gorgeous spot to enjoy the view to the garden without being bothered by insects or inclement weather!

Since it was mid-May, the late tulips were still looking gorgeous and Shirley had filled vases….

….. and bottles with them from her cutting garden.

Off we went past a towering sugar maple tree and stone wall toward the still-awakening perennial garden.

We passed the old, beautifully-restored 18th century barn on the right and more of the amazing stone walls that characterize Brigham Hill. The house and barn are part of the parcel of land purchased in 1975 by Shirley and Peter Williams. In time, Shirley and Peter purchased a large, adjacent piece of land and in 2007 they gifted a conservation restriction on the land to the Grafton Land Trust; its name is the Williams Preserve. But in those early days after their children were raised, the house and barn restored and the stone walls rebuilt, they were ready to begin gardening in earnest, at times seeking the expertise of designer/plantsman Warren Leach of Tranquil Lake Nursery in Rehoboth MA.

There were late daffodils and lots of fragrant lilacs nestled beside the stone walls.

Edible gardens are a big summer focus at Brigham Hill but I had never seen an espaliered apple using the heat of a stone wall to produce fruit.

Rhododendrons looked lovely, too.

Though billowing beds in the perennial garden form the focus in this area later in the season, I was happy to find this rustic, little red cedar pergola with….

….. bleeding hearts and Japanese hakone grass (Hakonechloa macra ‘Aureola’) looking fresh and lovely in a shady planting that also featured…

….. a stunning array of Japanese painted fern (Athyrium niponicum var. pictum) with bloodroot foliage (Sanguinaria canadensis).

I am a great fan of drama in the garden and this Warren Leach-designed dark border at the barn tickled my colour fancy a lot!

The big plants are hardy ‘Grace’ smoke bush (Cotinus hybrid) kept pruned into a columnar shape and tender black cordylines in pots.

At their base were the dark tulip ‘Queen of Night’ and the emerging black leaves of cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris ‘Ravenswing’).

Nearby, a cold frame contained an assortment of lush leaf lettuce for spring salads….

… while around the corner were Shirley’s annual seedlings, including varieties of love-in-a-mist (Nigella damascena), statice and amaranth.

Across the way, a shade-dappled woodland on a rocky outcrop beckoned to us. At one time, according to a story by Carol Stocker in the Boston Globe, this was originally “a hill overrun by Japanese knotweed and poison ivy.” Warren Leach found original granite foundation stones from the 18th century barn and “cellar holes” left as remnants of old colonial settler homes and used them to create the pond, rill, small waterfall and rugged stone steps that makes this feature so magical.

I was enchanted by the reflections of the chartreuse spring tree canopy in the pond.

Large granite pieces form sturdy steps…

…. while water bubbles down between stones.

Velvety moss is a major part of the charm of this garden….

…. but it is also a garden of sedges and woodland plants including greater yellow ladyslipper (Cypripedium parviflorum var. pubescens)….

…. which is such an iconic native orchid for the northeast….

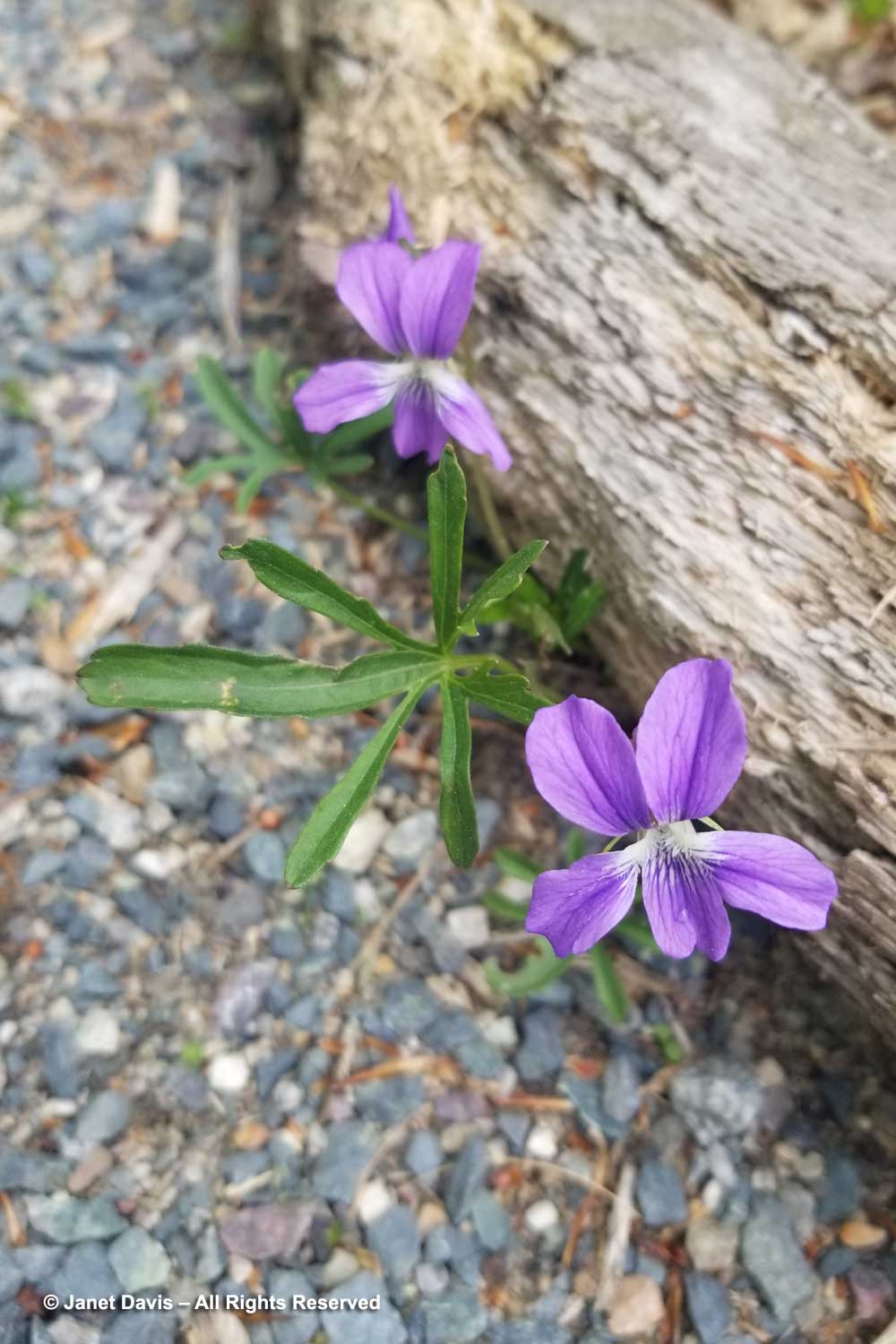

… and Jacob’s ladder (Polemonium caeruleum)…

…. and crested iris (I. cristata).

This was a pretty combination of Virginia bluebells (Mertensia virginica) with yellow wood poppies (Stylophorum diphyllum) and ostrich ferns (Matteucia struthiopteris).

Rhododendrons were flowering with the ferns in the woodland, too, and….

…. at the very edge, tulips grew in a carpet of Virginia bluebells.

Back out in the open, late-season tulips were still looking good in Shirley’s raised cutting bed. What a luxury, to have armfuls of tulips for vases!

Next up was the chicken coop with its succulent green-roof planted with sempervivums or (haha) “hens-and-chicks” – a nice pad for the resident hens.

Strawberry plants were flowering behind critter-proof protective mesh.

Caned berry bushes have their own enclosure.

The back of the house with its dining terrace features more stone walls, their geometric lines echoed in the clipped hedges. Later, colourful perennials will emerge in the beds here. Those stone steps lead into the walled vegetable garden, still unplanted.

If you visit a garden in May, you see spring things, but I did regret not being able to see the large, raised-bed vegetable parterre behind the stone wall in summer.

Trees, both in the native forest on the property and cultivated in the garden, are a focus at Brigham Hill Farm. This featherleaf Japanese maple is a good example, as are…

…. the trees in the “arboretum”, including native flowering dogwood (Cornus florida)…

…. which looked resplendent against the blue May sky.

We circled around to the front of the house and met Shirley’s guest, Kathleen Ladd, departing with a giant bouquet of freshly-cut lilacs and tulips, a lovely gesture from a gardener who also shares the expansive beauty of Brigham Hill Farm with many charities and groups for fundraising events

At the gate, we said farewell to my friend, gardener and well-known potter Kim Cutler (left), and to Shirley Williams, thanking her for her generosity in sharing her garden with us, strangers from Canada! It was a highlight of our spring road trip. (Stay tuned for Chanticleer!)

********

Want to see some of the other inspiring private gardens I’ve photographed?

Here is Katerina Georgi’s garden in Greece

This is tequila expert Lucinda Hutson’s fabulous garden in Austin, TX

The spectacular Denver CO garden of Rob Proctor & David Macke

The Giant’s House in Akaroa NZ – a mosaic masterpiece

Architect & art collector Sir Miles Warren’s garden Ohinetahi in NZ

Garden designer Barbara Katz’s gorgeous garden in Bethesda, MD

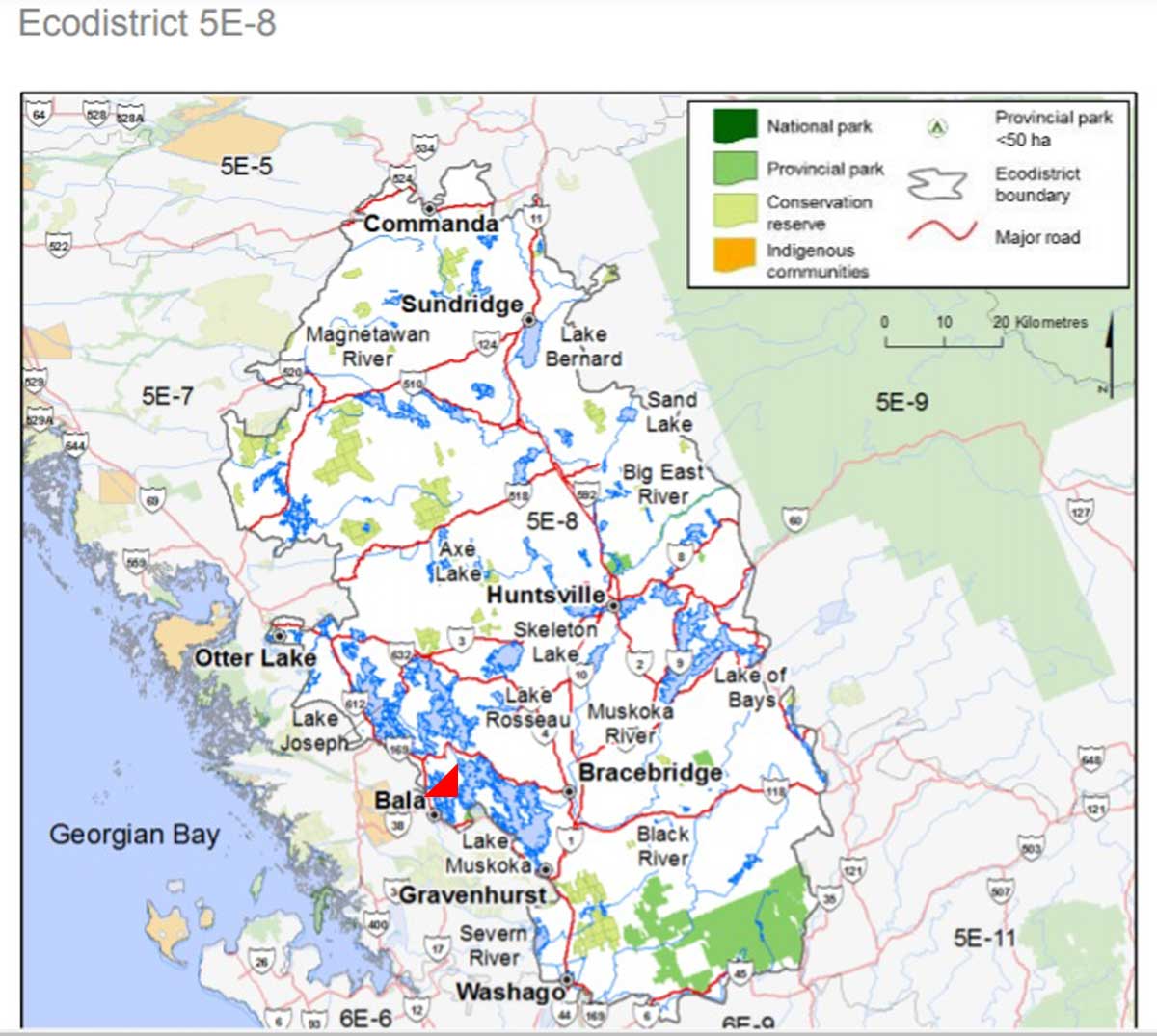

My friend and plantswoman Marnie Wright’s garden in Bracebridge ON