The final morning on our Adventure Canada Eastern Arctic expedition saw us sailing up the 190 km-long (120-mile) Kangerlussuaq Fjord. Unlike some of the turquoise blue water we had seen in Greenland, this one was decidedly murky, the product of all the silt that flows into it from the ice sheet. In fact there are actually silt quicksand patches up to a kilometre in size in the area, and tourists are cautioned about going near them. Kangerlussuaq is the Greenlandic word for “Big Fjord”, thus the reason why people might be confused to find there’s a second, non-related Kangerlussuaq Fjord on Greenland’s east coast. Although the fjord crosses the Arctic Circle, the effect of ocean currents is that it does not freeze. Thus, historically, it’s been a centre for fishing and whaling. We left the ship for a short bus tour of the region.

Its relatively mild weather was instrumental in Kangerlussuaq being established as the military base “Bluie West 8” (with Bluie the Allied code word for Greenland) by the Americans during World War II, when it was used as a refuelling and staging ground for flights onward to Europe. After the war, it became part of the American Cold War push to monitor Russia, in conjuction with Thule Air Base in north Greenland. It is now the country’s main air transport hub, and the site of its biggest commercial airport. On our tour, we paid a visit to the town museum, which is a rather weird hybrid of displays honouring the U.S. Air Force and SAS Airlines, which was once based here.

Muskox roam these parts and we would see some in the distance later in our tour, but this one stood still for a photo.

I loved this simple bouquet of native cotton grass (Eriophorum spp.) on the windowsill.

We headed over the nearby bridge towards the hills nearby. Qinnguata Kuussua is a river that drains the nearby Russell Glacier and feeds into the fjord. In the old days, it was called the Watson River. When I snapped this photo on August 6th showing the might of the rushing glacial meltwater…..

….. I didn’t know that in July 2012, one of the warmest summers ever recorded in Greenland, a large section of the bridge was completely washed out by runoff…..

….taking a tractor and operator with it. He survived!

Later today, our flight home would leave from the runway in front of the white and red buildings, which we spied from a rocky hilltop above town.

I used my zoom lens to get a better look at the airport area. Although some of the buildings looked like the paintbox-coloured prefabs from Denmark that we’d seen in other Greenland towns, the flat-roofed hostel on the right, called “Old Camp”, is a former U.S. Air Force barracks.

As we walked about up there in the hills, I found Arctic blueberry (Vaccinium uliginosum) and sampled a few out of the hand. The verdict: very similar in taste to the lowbush blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium) that grow around our cottage on Lake Muskoka, in central Ontario.

I did spot a muskox, which I had to take on faith from our guide – because it looked like a slow-moving black rock from where we sat.

And then, for my first time in Greenland, I looked across the valley and spied the ice sheet, just visible over the rocky mountains, with the Russell Glacier in front, below. What a thrill that was! Tourists can take bus tours up onto the ice sheet. “What do they do?” I ask our tour guide. “They throw snowballs and take photos and get back on the bus”, he said. “Oh,” I answered. But how I would love to have gone up that road to stare off at the endless frozen white plain!

**********

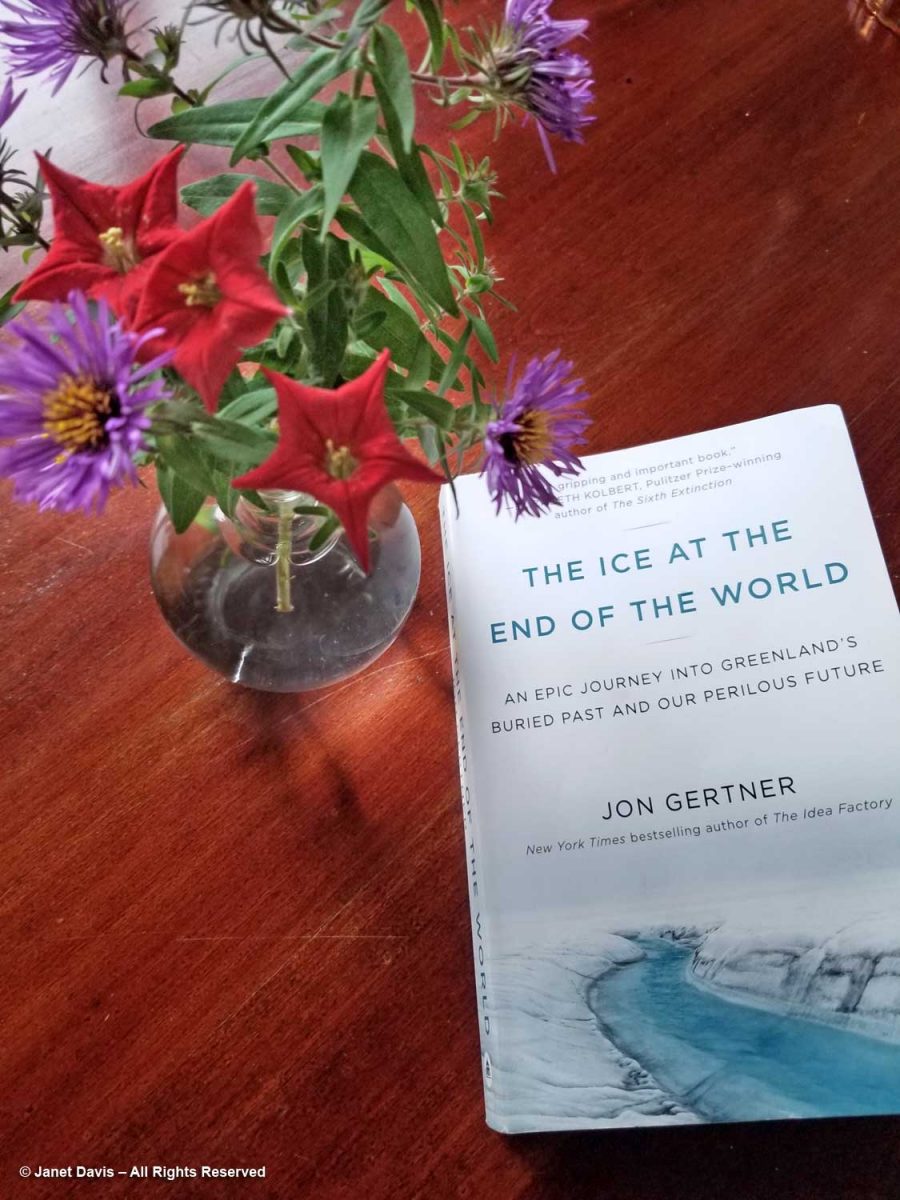

I’ve been thinking about Greenland’s ice sheet over the past two months, as I’ve published these ten blogs about our trip with Adventure Canada to Nunavut and Greenland. As is always the case with my travels, I tend to discover more about the natural and cultural history of the places I’ve visited after I return home. That’s when I go through my photos and use the internet to help me understand what I saw. In the case of Greenland, it’s what I only caught a glimpse of that I longed to know more about, which led me to buy this book by Jon Gertner, ‘The Ice at the End of the World‘, which I mentioned in my blog on Ilulissat.

I finished it just a few weeks ago, full of astonishment at the stories of the explorers, military types and scientists who travelled to the ice sheet and took on the challenge of its extreme conditions. Some wanted simply to cross it, because that had never been done, even by the Inuit who inhabited its more temperate, rocky shores. Ice covers almost 80% of Greenland, as you can see in the Google map below. At more than 2,670 km ( mi) long and 1,050 kim (650 mi) wide from east to west at its widest point, it encompasses 972,000 sq km (375,000 sq mi). Look how many United Kingdoms would fit into Greenland!

On the Greenland side, our ports of call had been in the narrow, populated region along Greenland’s southwest from Uummannaq in the north to Kangerlussuaq. Much of the rest of Greenland’s coasts are as unapproachable now as they were when the first explorers visited in the late 19th century.

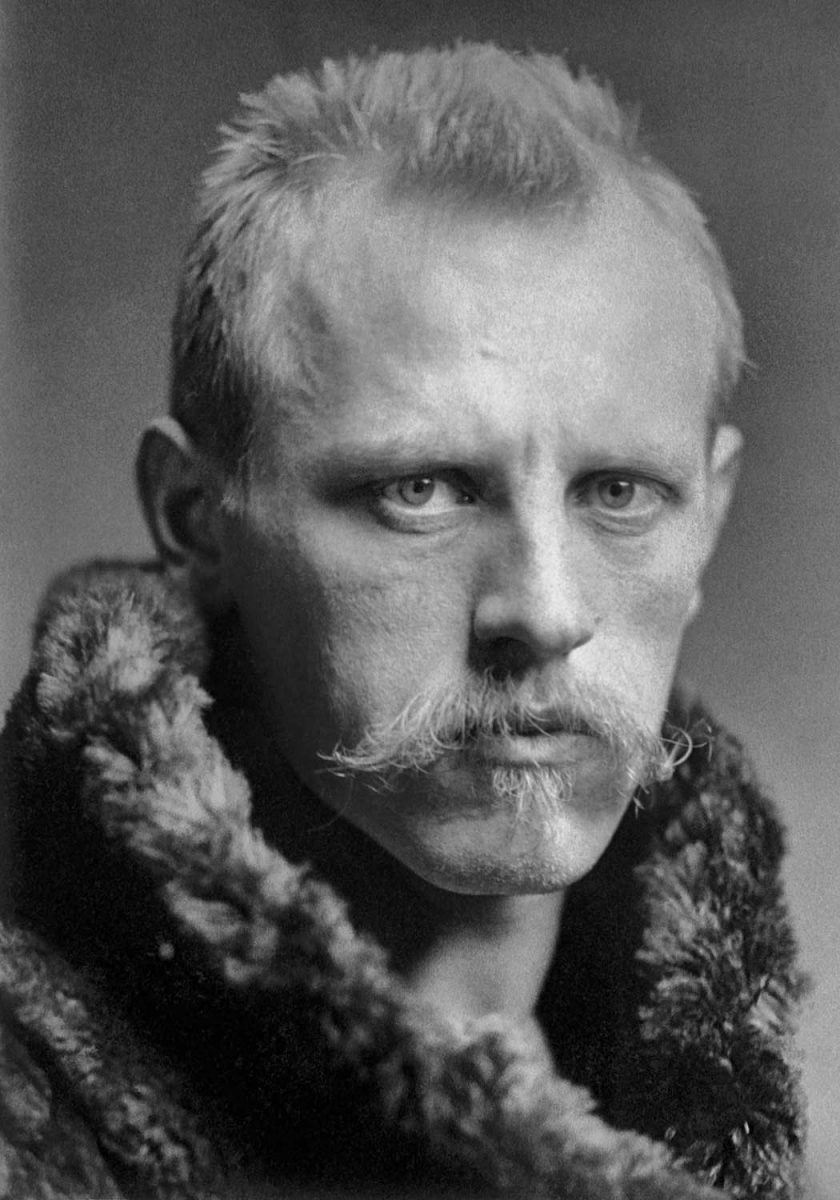

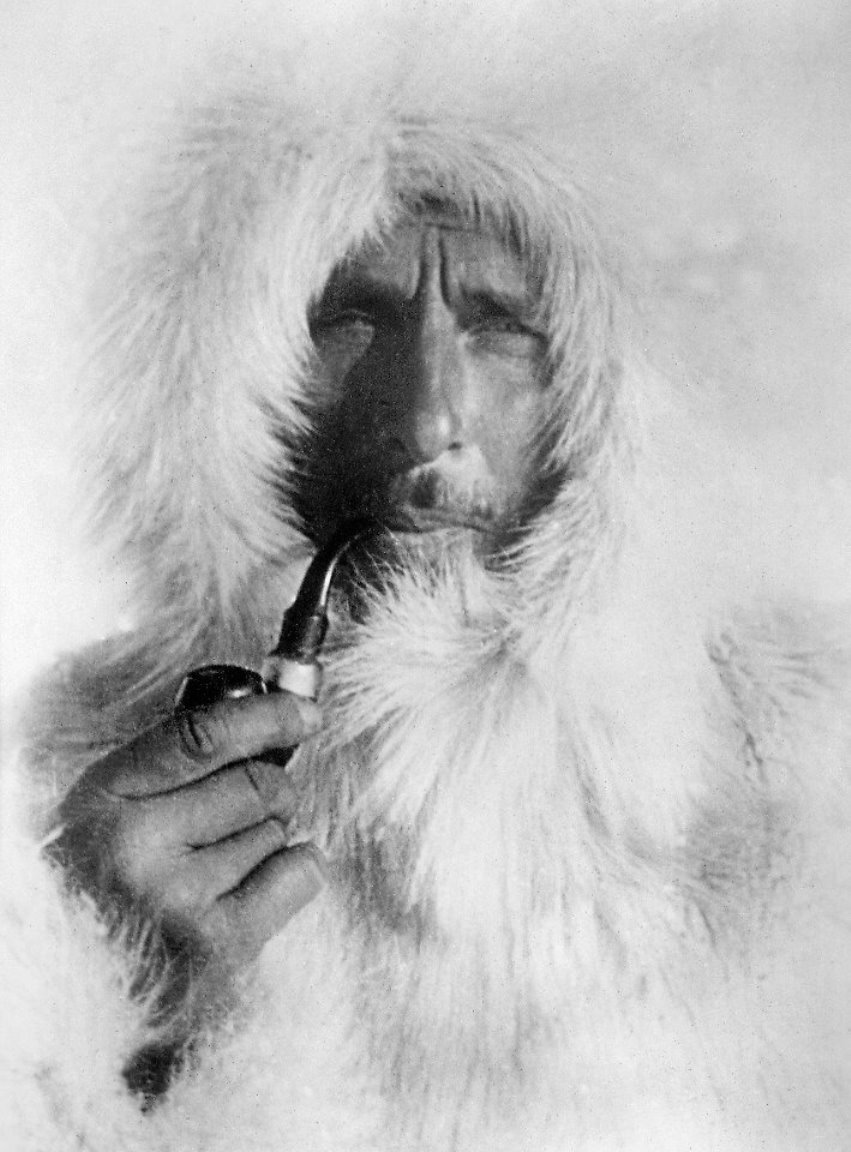

Having read Gertsen’s book from beginning to end, his chapters on the first man to cross Greenland, Norway’s Fridtjof Nansen (1861-1930), were my favourite. Much has been written about Nansen, who was something of an athletic legend in Norway, having won several consecutive national cross-country skiing championships as a youth. Born in what is now Oslo to a well-to-do family who encouraged hard work and public service, his passion for the Arctic took hold at the age of 20. Newly graduated from university in zoology, he travelled to the Arctic on the sealing vessel ‘Viking’, making observations on animal life, sea ice and ocean movement. He also began to write copious journals that have enriched the history of exploration. When he caught sight of the mostly uninhabited east coast of Greenland, he was entranced, for no European had been up on the ice. After returning to Norway, he spent 6 years as Curator of Natural History at the Bergen Museum, in the process earning his PhD.

He was 27 when he launched his bid to make the first documented crossing of the Greenland ice sheet, spending six months raising money and hiring five fellow adventurers who were skilled skiers. After journeying from Norway via Denmark, Scotland and the Faroe Islands, his team set sail from northwest Iceland on the sealing ship ‘Jason’ on June 22, 1888, heading roughly towards Cape Dan on Greenland’s east coast. Nansen’s rationale was simple: going east to west across the ice sheet would be a one-way trip, since no ship would chance a pickup of the explorers on the wild east coast, whereas the west coast was navigable in season. Thus his motto: “West coast or death.”

But thick pack ice kept the Jason far from the eastern shore. On July 17th, once their destination was sighted within 10 miles, Nansen and his men took their supplies in two small boats over the side of the ship onto the ice floes. Their adventure almost ended there, for they spent 10 days off the coast in the freezing North Atlantic, rowing when they could, or camping on the floes when the sea ice thickened, all the while being driven south with the ice. Ice floes cracked beneath them and they rocked on the waves which crashed around them and carried them far out to sea. Finally, the ocean currents worked to their favour; eleven days after they launched they were able to make it to shore, but about 120 miles south of where they intended to begin. After rejoicing in the grasses and heather and having a picnic with hot chocolate, they began the trek north, alternately rowing the boats or hauling them on shore, greeting a few Inuit men in passing kayaks or in their encampments as they travelled. Given the lateness of the season, Nansen elected a more southerly route towards Godthaab (present-day Nuuk) that would cut significant mileage off their trip.

On August 11th, they began their ascent towards the ice sheet, encountering the treacherous crevasse zone at its edge. As Gertner writes: “What proved to be especially treacherous about the crevasse zone, Nansen would learn, wasn’t the largest cracks but the smallest. Many were snow-shrouded and undetectable, so much so that he might be moving along a seemingly smooth surface and plunge down suddenly into a fissure in the ice, saved only by a reflexive urge to outstretch his arms. The fall would leave him up to his armpits in snow, his legs dangling over nothingness.” (In August 2020, as I wrote in my blog on Ilulissat and the Jakobshavn Icefjord, those treacherous crevasses or moulins would claim the life of a modern-day scientist, Konrad Steffen, who ventured out alone from his Swiss Camp near Ilulissat, only to lose his life, likely because of a failed snow bridge.) Nansen’s team’s heavy sledges were made of ash and steel; their skis of oak and birch. But their skis were still packed away, in favour of boots with crampons for the steep angle in the crevasse zone.

By September 2nd, the ice sheet levelled out to a gradual uphill slope and the team switched to their skis. On some days, the walls of their tents, which at night had often been rimed with frost as the temperature sank to more than -40C/-40F, served as sails for ski-sailing across the flatter parts of the ice.

On September 12th, after reaching the summit of the ice sheet at around 8,000 feet, the ground sloped away and they realized they were on the downward slope. Five days later, two months after leaving the Jason, they heard the song of the snow bunting and knew they were near the west coast. On September 17th, they sighted land, but they were now at the crevasse zone of the west coast of Greenland. It would be another week of advancing, retreating, moving diagonally and sideways, as if on a chessboard, before descending on September 24th from a steep slope onto a bed of gravel. Even though they were 90 miles from their destination at Gothaab, they were now at sea level. They had done it! They would only need to build a boat from willow branches and the canvas from their tents! Nansen christened it the “tortoise shell” but it was not their magic carpet, for the fjord where they landed was too shallow, so they had to drag their boat along the shore in sections of their journey. Finally, on October 3rd, they paddled into the harbour of Godthaab, to be greeted by a Danish official. “All along the western coast of Greenland, they had been waiting for Nansen’s arrival.” The last boat for Europe had departed two months earlier, so the team had to spend winter in Greenland, finally arriving home in May 1889.

In 1893, just four years after arriving home and writing two books on the trek across Greenland (1890) and Eskimo Life (1891), Nansen returned to Greenland with a specially-constructed ship called Fram, below, whose three-layered hull had been designed to his specifications to withstand freezing in the pack ice. It would survive its three-year stay in the ice-filled waters off Greenland and return to Norway like the maritime hero that it was – eventually, the only wooden ship to have reached both the furthest north (with Nansen) and south latitudes (later to Antarctica with Roald Amundsen). As for Nansen, he would go on to a storied career, as a professor at the University of Oslo and Norway’s Ambassador to London. In 1922, following the First World War, he received the Nobel Peace Prize for his humanitarian work, especially for the identification card called the “Nansen passport”, issued by the League of Nations as a travel document to stateless refugees. It enabled the release and repatriation of more than 450,000 prisoners-of-war. He was also the international mediator in the Greek-Turkey conflict and the war between Armenia and Turkey.

Gertner’s book goes on to describe in vivid detail the exploration stories of Robert Peary (1856-1920), one of the more colourful and fame-absorbed American figures, who in spring 1892 left his American wife Josephine on the west coast of Greenland and charted a northern route across 600 miles of the ice sheet with his assistant Matthew Henson to land at a remote, unexplored part of the island’s north coast.

On a later expedition, with his wife back home in the States, he not only left behind the American flag on a small, snowy hillock at what he judged to be the North Pole, a “first in history” that was later determined to be off the mark by several miles, but also two sons, born in 1900 and 1906 to his teenaged Inuit mistress Aleqasina or “Ally”. His Greenlandic great-grandson, Hivshu, or Robert Peary II, has a fascinating website in which he explores the relationship of his American great-grandfather (the father of his grandfather Kale), to the Inuit people he lived with in Greenland, including six he took back to the Natural History Museum in New York, with tragic consequences.

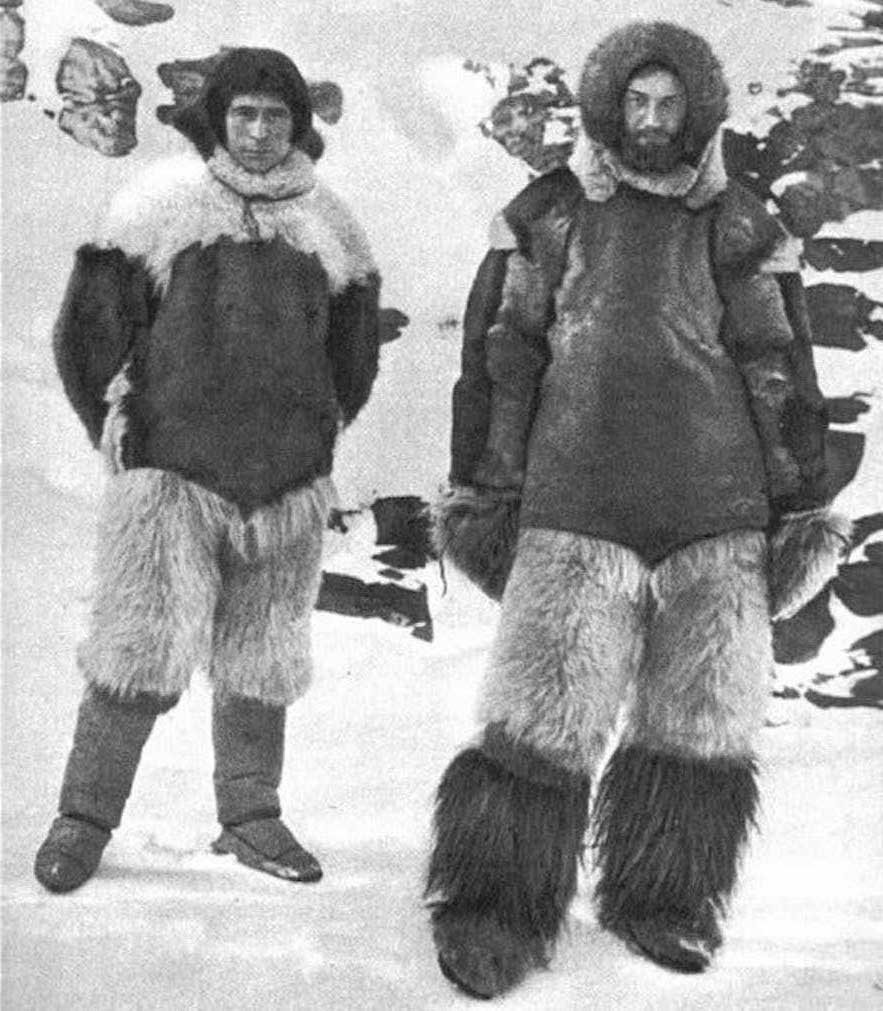

Knud Rasmussen (1879-1933), the Greenland-born explorer whose museum home we had visited in Ilulissat days before, made several trips throughout the Arctic. In 1912, he and his Danish friend Peter Freuchen, right below, undertook the First Thule Expedition, a 1000 km (620 mile) gruelling voyage across the ice sheet with four sleighs and 53 dogs. In three weeks, they reached Peary Land near the north coast, named for Robert Peary and his expedition 20 years earlier. In fact, Freuchen found Peary’s time capsule buried in a rock cairn: a brandy bottle with a note inside. As was the custom, Freuchen removed Peary’s note (to be returned to the sender) and left his own note within.

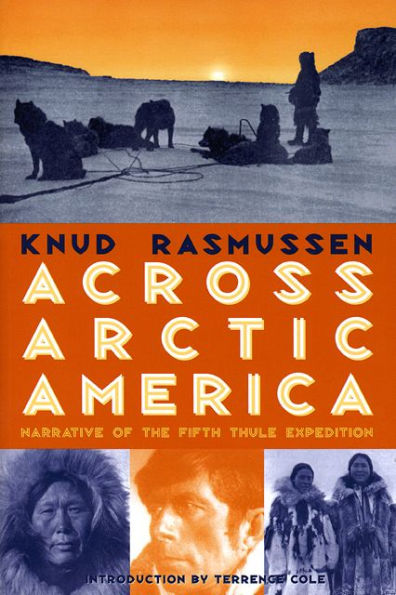

Rasmussen’s Second Thule Expedition in 1917 across the ice sheet to the northern fjords aimed to learn about the area’s geology and map its glaciers. Tragically, a lack of food and hunting opportunities resulted in the starvation death of a Danish botanist and the disappearance and presumed death of an Inuit team member. But Rasmussen is most famous for his Fifth Thule Expedition, begun in 1921, lasting until 1924, and stretching by dogsled right across Northern North America to Siberia. This 20,000 mile expedition was ethnographic in nature, with Rasmussen conducting interviews with the northern peoples and collecting songs. At the end, he wrote a popular book called Across Arctic America, below. As the modern ethnographer Wade Davis says of Rasmussen, “In character, heart, motivation and vision, Rasmussen was everything that Peary was not. What he achieved in a life cut short — he would die at 54, having eaten an Inuk delicacy tainted with salmonella — a man of Peary’s ilk could neither appreciate nor understand. An enamelled faith in the superiority of his own culture left Peary half-blind, even as he stumbled north to the pole.”

Many of us know the German explorer Alfred Wegener (1880-1930), who was also a geophysicist and meteorologist, for his famous contribution to our understanding of plate tectonics. Having observed that the shapes of adjacent continents seemed to fit together across oceans like a jigsaw puzzle, he coined the phrase “continental drift” in 1915 in his book The Origins of Continents and Oceans. The mechanism he proposed was wrong, but it was the first time a scientist had theorized that earth’s land masses might have broken apart and separated from a larger land mass (later called Pangaea). But Wegener had another passion in life: the exploration of the Arctic born from, as Jon Gertner writes, “a recurrent craving for intense physical experiences“.

As a 25-year-old in 1906, Wegener was chief scientist of the 28-member Denmark Expedition to chart remote and unexplored areas of Greenland’s north coast. His diaries from that trip (which also included a young Peter Freuchen) featured measurements still important in modern historical records, of air pressure, temperature and wind. But the expedition was gruelling, and also resulted in the loss of its three Danish leaders to starvation and exhaustion on the ice sheet.

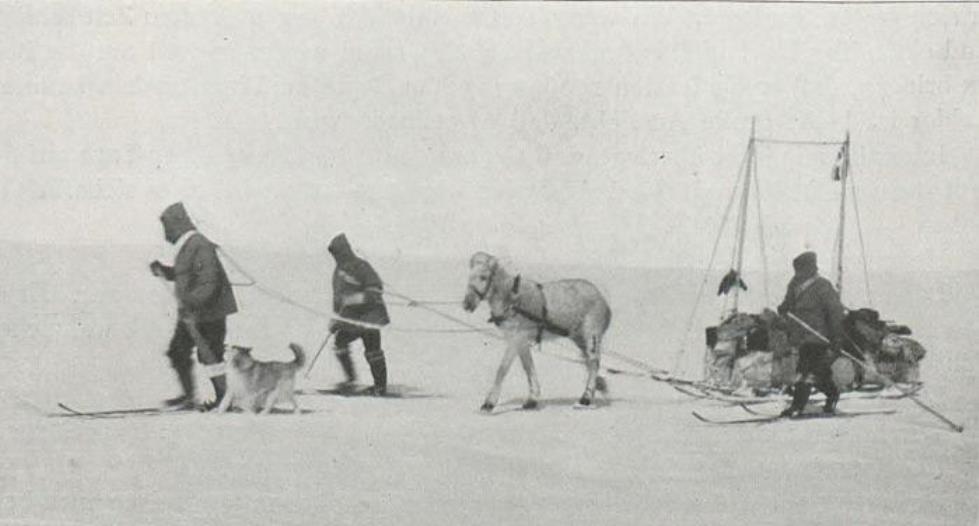

It would not daunt Wegener. In 1912, he joined a colleague from the Denmark expedition, J.P. Koch, along with Vigfus Sigurdsson from Iceland and Lars Larsen from Denmark to depart Danmark Harbour on the east coast and overwinter on Greenland’s ice sheet — the first time any expedition had attempted to do so. It would be called The Danish North Greenland Expedition. Instead of sled dogs, they used 13 Icelandic horses, believing them to be superior for hauling supplies up the steep promontories leading to the ice. During the journey, they would be forced to slaughter some horses to feed other horses, with the remainder put down as they weakened and became sick; a calving glacier would destroy half their supplies and break many of their sleds; Wegener would break a rib falling on glacier ice; Koch would drop 40 feet into a crevasse and break his leg, confining him to bed for 3 months, while the temperature outside their camp fell to -58F (-50C). As they conducted their research, observing the northern lights, digging a pit 23 feet deep to measure the snow temperature while noting the layering of the ice sheet, they struggled across 700 miles of ice sheet, starved and exhausted. On July 15, 1913, a year after they began and very close to their destination, they sat down to eat their final meal — a stew made from their little companion Icelandic dog Gloë — when Wegener spotted a sailboat in the fog off the coast. It would be their rescue.

In 1930, Wegener made his final assault on Greenland’s ice sheet, along with three German scientists, Johannes Georgi, Ernst Sorge and Fritz Loewe. But the ice break-up on the west coast was very late, and they were forced to remain on the ship through May until mid-June, five weeks later than planned. They hired Greenlanders to haul the 240,000 pounds of supplies up the steep, crevasse-filled ice of the Kamarujuk Glacier to their initial camp, but warm summer weather and mosquitoes made it slow going. Georgi and some Greenlanders went ahead to set up their camp “Eismitte” or “middle ice”, 250 miles away. He was joined later by Sorge — the plan was that this pair would spend winter at the camp alone, detonating explosives to measure the thickness of the ice sheet via seismic readings and doing meteorological research. They made underground caves in the ice which were much warmer than their above-ground tents, in time making their bunks right on the older “firn” snow. But they knew they would not survive winter without fuel, so sent a note back to Wegener saying if supplies hadn’t arrived by October 20th, they would return to the west coast camp on foot. Back at the first camp, Wegener had planned to use two propeller-driven sleds, below, to bring the rest of the supplies and men to Eismitte, but they did not operate well on the slopes and in the deep snow and the idea was abandoned.

It was the first day of autumn, September 21, 1930 and dangerously late in the season when Wegener finally left his west coast station for Eismitte along with 130 dogs pulling fifteen loaded sleds. He received the note from Georgi and Sorge en route. More than 5 weeks later, as Gertner writes, Sorge and Georgi “were in their ice cave on the afternoon of October 30, on their bunks and ensconced in reindeer fur, when Sorge hear the rasp of dogsleds and some muffled voices on the surface of the ice above. It was -60 degrees Fahrenheit outside. ‘They’re coming!’ he shouted.” Wegener’s journey from the west coast camp had taken 40 days, and though he had started with Loewe and 13 Greenlanders, they were now only three, the two German scientists and Rasmus Villumsen, the dogsled driver. The other men, convinced they were on a death trek, turned around and returned to the coast. Now the five men were together in the ice cavern, with Loewe suffering frostbite to his feet that would require the pocket-knife amputation of eight of his toes 10 days later. Wegener celebrated his 50th birthday on November 1st and posed with Villumsen for the photo below before beginning the treacherous journey back to the coastal camp. It was the last time they were seen alive.

In an era when polar explorers were a little like astronauts, their exploits were followed by newspapers and radio announcers everywhere, but particularly in Germany. With no radio at Eismitte and no word from Wegener and Villumsen that winter either, the world was left to ponder the ominous silence from Greenland. In April 1931, a team with 7 sleds and 81 dogs departed the west coast and found the abandoned motorized sleds on their route, which they used to travel to Eismitte. When they arrived, the truth became clear: the great explorer was gone, along with the sled driver. They would later find Wegener’s skis positioned upright in the snow at Mile 118 halfway to the coast, his body buried in sewn sleeping bags; the supposition was that he had died of heart failure in his tent in the tremendous effort to ski alongside the sled in winter conditions. Villumsen’s body was never found, nor were Wegener’s journals. His widow asked that he be left buried there and a 20-foot high iron cross was erected in the snow nearby, below, where he remains today beneath 90 annual layers of snow, firn and ice on the ice sheet. As Gertner writes: “Ultimately the scientist would be subsumed into the subject of his studies“.

Research work continued that summer at Eismitte. A final dynamite blast recorded seismic “reflected wave” readings that indicated bedrock lay between 8,200 and 8,850 feet (2,500 – 2,700 m) below the snow. The weight of the snow evidently meant that Greenland was lower in its centre than at its mountainous coasts.

Gertner’s book, which I heartily recommend, goes on to describe the post-war, scientific exploits of France’s Paul-Émile Victor (1907-1995). An ethnologist and wartime U.S. Air Force pilot (he was outside France when Germany occupied it and chose to enlist in the U.S.), he had lived amongst the Greenland Inuit in 1936, learning their language and writing a book called My Eskimo Life. In 1947, he formed Expeditions Polaires Francaises (EPF) to do research at earth’s polar regions. And on July 17, 1949 he reached the 9,900-foot elevation at the centre of the Greenland ice sheet in a convoy of U.S. military surplus, Studebaker-made “Weasel” tracked vehicles he’d found post-war in Fontainebleau outside Paris. By then the old German camp Eismitte was buried under 40 feet of snow and firn. Victor, who was greatly assisted by the fact that airplanes could now do supply drops on the ice sheet, would go on to do scientific research in Antarctica as well.

But it was the outcome of the second world war and a U.S. treaty with Denmark that ushered in the American military presence in Greenland. In fact, in 1946 the U.S. had proposed buying Greenland, offering $100-million to Denmark, an offer that was not accepted. (Does that sound familiar? Trump floated the idea in 2019, with the same result.) After Russia detonated its first atomic bomb in 1949, the Cold War began in earnest. Greenland was given the code name “Bluie” and the Americans constructed the Thule Air Base in 1951-52. their principal base in the country, along with several satellite bases such as Kangerlussuaq or “Bluie West 8”, the site of our last day on this Adventure Canada expedition. A few years later, Thule became the supply point for an even more ambitious U.S. military endeavour: the creation of a massive, nuclear-powered, under-ice base called Camp Century. What was it? Well, no one can tell the story better than the authors. Here is the U.S. Army’s propaganda film on Camp Century.

This is what it looked like from the air in 1959, below. Even television news anchor Walter Cronkite came to visit. The network of tunnels had to withstand the massive overburden of the ice sheet’s snow and required regular shaving of firn from their walls “as much as 40 tons a week“. Though the camp would be ultimately doomed by its physical environment, it was felt to be a vital asset in protecting North America from Soviet aggression.

But something else was happening as the U.S. established its military presence in Greenland: scientists tagged along via the budgetary largesse, learning as much as they could about the secrets of the ice via the newly-created US Army Corps SIPRE (“Snow, Ice and Permafrost Research Establishment”). Its chief scientist, Swiss-born glaciologist and former Rutgers professor Henri Bader (1907-1998), aka “the iceman”, hired young researchers like Carl Benson, Chester Langway, Lyle Hansen and Herb Ueda to discover all they could about Greenland’s ice in Camp Century’s Trench #12. Even as the military was dreaming up plans to store nuclear-powered Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles under a vastly extended Camp Century — a theoretical strategy called “Operation Iceworm” — the ice scientists were using a massive oil rig found lying around in Oklahoma in 1964, below, to drill down to retrieve ice cores that had formed from snow that fell tens of thousands of years earlier. As Henri Bader said of the ice bubbles formed in the ice and the information that could be gleaned from them: “Snowflakes fall and leave a message.” Appropriately, it was July 4, 1966 when they hit bedrock, having cored Greenland’s deep ice to a depth of 4,450 feet (1,356 m). All the ice cores were stored by their age, so the researchers could analyze historic changes in weather and atmospheric particulates over thousands of years.

Even as the military was winding down its operation in Greenland, the ice core research at Camp Century dovetailed with an emerging focus worldwide on the environment. The late 1960s saw heightened attention being paid to air quality and the role of increasing levels of Carbon dioxide from fossil fuel emissions and other greenhouse gases in earth’s atmosphere. Ice cores were catalogued, not just from Greenland, but from Antarctica, Alaska and many other cold regions in the world, for ice held the story of earth’s climate, reaching back thousands of years before the first steam engine sent pollutants skyward. The photo below is inside the freezer at the National Ice Core Lab in Denver, Colorado.

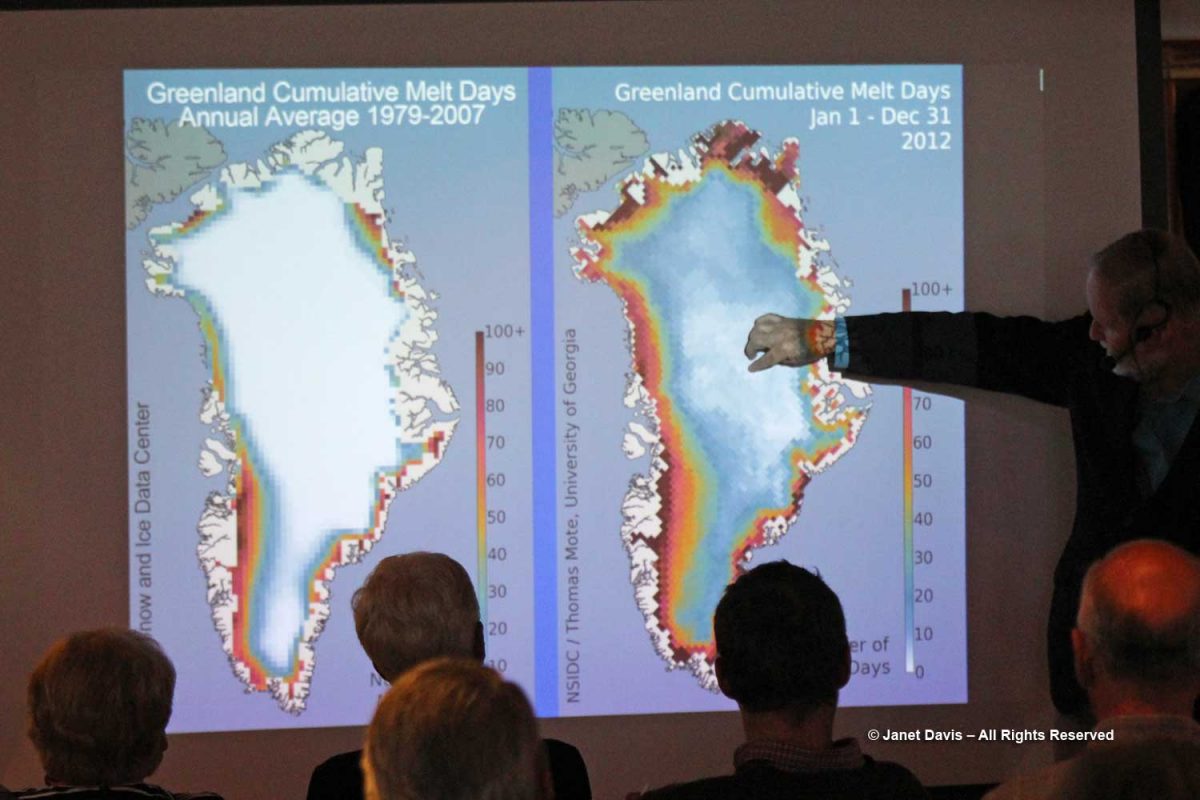

Greenland figures in climate change studies in another way, too. In summers like 2012 and 2018, when massive parts of the ice sheet surface melted in record warm temperatures, the albedo effect — the measure of reflectivity of a surface, in earth’s case from the sun’s rays — creates a positive feedback loop with the atmosphere. In other words, white ice reflects the sun’s ray’s away from earth, maintaining a cooler surface; dark puddles of meltwater absorb solar rays, increasing ambient temperatures over a large part of earth’s polar surfaces. On this Adventure Canada expedition, we learned about albedo from Jim Halfpenny, one of the on-board resource naturalists, below. Though annual melting of Greenland and Antarctica’s ice sheets have not yet contributed significantly to earth’s sea level rise, since winter temperatures and annual snowfall tend to keep conditions in relative equilibrium, the great fear is that continued global warming beyond certain threshold levels will cause a cascade effect that sees rapid melting of the ice. When that happens (and at currently rising global temperatures, it’s a matter of “when”, not “if”), the rise in global mean sea levels is forecast to inundate low-lying islands, land masses and coasts.

Jon Gertner’s book goes on to talk about modern research on the ice sheet, parts of which I included in my blog on our visit to the Jakobshavn glacier at Ilulissat days earlier. His story in the New York Times of flying in an IceBridge data-gathering plane over the ice sheet on one of his four trips to Greenland is compelling. Here’s a NASA photo from a September 2019 IceBridge flight over the west coast of Greenland by Matt Linkswiler.

But I was especially intrigued by Gertner’s description of the work of leading ice sheet researchers, the husband-and-wife team David and Denise Holland of NYU’s Environmental Fluid Dynamics Laboratory and The Center for Sea Level Change at Abu Dhabi NYU . As Dr. David Holland’s professional page states, their research “focuses on the computer modeling of the interaction of the Earth’s ice sheets with ocean waters, and the acquisition and implementation of observational data for model improvements.” What I loved is that the Hollands and Dr. Aqqalu Asvid-Rosing of Greenland’s Department of Natural Resources have figured out a way to measure the deep ocean temperature right at the calving mouth of Jakobshavn’s glacier, in a section known in glaciology as the “mélange“, the slush that clogs the glacier’s outlet, and also at Cape Farewell, a headland at the southern tip of Greenland. How? They have affixed temperature sensors to local seals, which swim to a depth of 1,200 feet, and to halibut, which inhabit the depths to 3,000 feet. Have a look at this film.

Below is a bearded seal with a freshly-affixed sensor, about to be released back into the ocean.

Clearly, as I reach the end of this blog series on our Adventure Canada expedition through the waters off Nunavut and Greenland, it might have been preferable (and less like a small book) to have done an entirely new blog on the ice sheet, but that last-day glimpse of the great white expanse from the hillside in Kangerlussuaq inspired me to learn its history. Fittingly, the little hamlet with the international airport is at the apex of research, on climate change as well as the history of its people and wildlife. As Jon Gertner writes: “In the local cafes, you could meet glaciologists, hydrologists, anthropologists, geomorphologists, and sedimentologists“, not to mention archaeologists and marine biologists.

*******

After our tour of the area around Kangerlussuaq, it was time to head to the airport, the duty-free shop, and onto the CanJet charter back to Toronto.

We flew off southwest over the tundra bound for Toronto and just like that, our lovely Arctic Explorer journey came to an end.

It was the voyage of a lifetime, and I feel I now know so much more about this little planet of ours: its northern people; wild animals; magnificent, green-in-summer tundra; unique flora; and its storied, precarious ice sheet.

********

This is the 10th and final blog in my series on the Eastern Arctic. Here are the 9 previous blogs :