The blog below is one of those little bits of fancy you think is just too silly and much too much work to pursue, then find yourself doing exactly that for three days straight. Why did I think it was worth the exercise to work on not-very-good photos of North Dakota, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia in order to present them to people who couldn’t care less about spotting Minot Air Force Base from six miles up? Well, I guess I could ask why people flying over a spectacular, sunlit tapestry of farm fields, canyons, mountains, rivers, lakes and towns can’t get their nose out of their novel or stop watching a recycled movie on a little screen long enough to appreciate the diversity of this magnificent continent we call home.

Plus, I’m a little obsessive. You might have noticed.

***********************************************

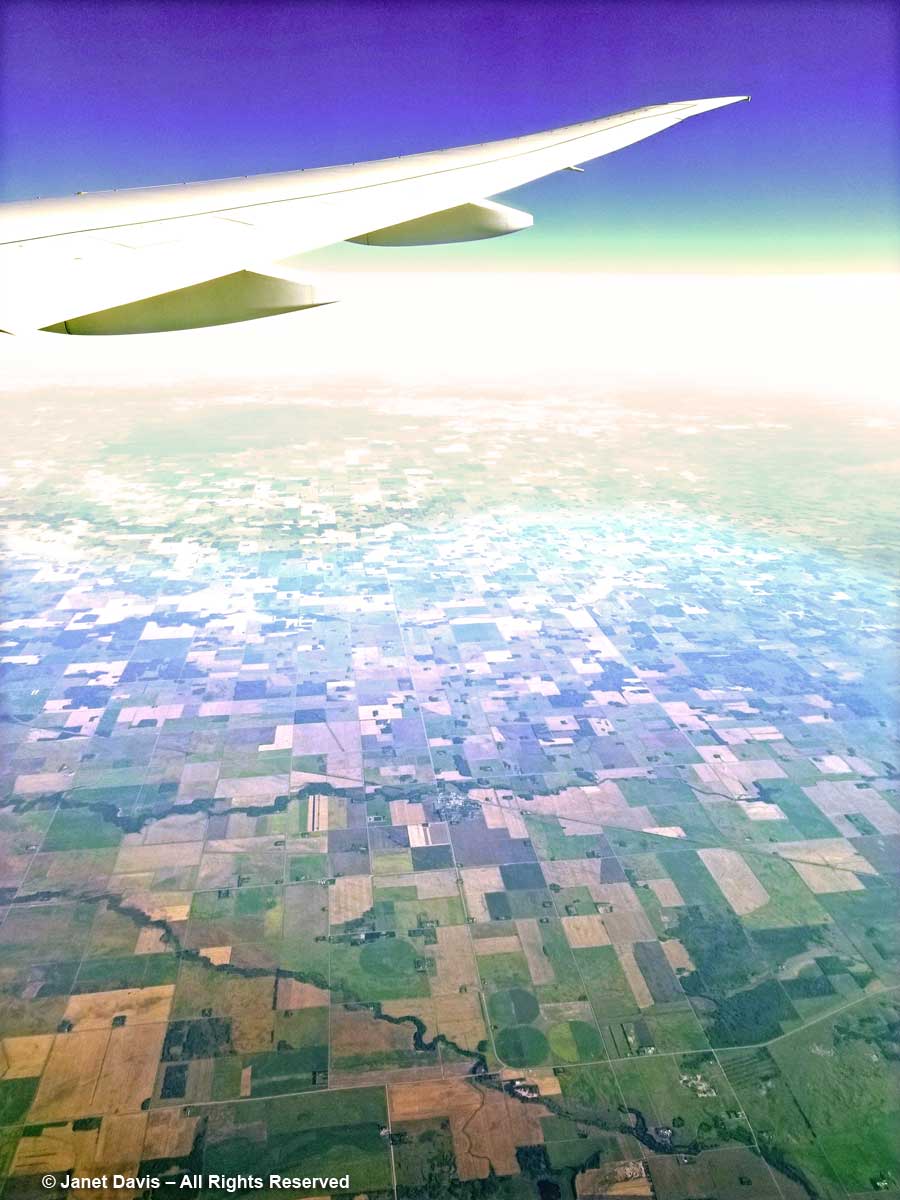

9:39 am – I’m nicely settled into my window seat of Flight 103 from Toronto to Vancouver, anticipating a little reading after an hour-long nap to overcome the fatigue that happens when your alarm rings at 4:45 am on a travel day. It’s a comfortable and fairly new Boeing 777 and my seat, 45K, is behind the wing on the right side, which gives me a nice view of the scenery below and to the north. I glance down as we cross the western shore of a Great Lake (Superior, I think) and reach for my phone, more for fun than anything, since I’m clearly not an aerial photographer and the Samsung S8, though a lovely little phone camera, has very limited resolution – especially at an altitude of more than 10,000 metres (6 miles) and a speed of 800 km (500 mi) an hour. What I see is this…..

10:01 am – Hmmm. Rhapsody in Blue… not the ideal. Airplane windows are strong, double-paned acrylic with UV filtration – and often splashed with rain drops or bits of grunge – so it’s a challenge to capture the scene on the ground the way your eyes see it. But once I start, I’m hooked. My next image is all blue as well, but with a lot of Photoshop post-processing (starting with Auto Colour, then various colour filters, shadow highlighting, contrast fixes, etc.), I manage to make it look like this, below. Whatever is in that window acrylic or shading, the camera senses skylight differently from the scene on the ground and blows the background out.

A way to fix that is just to delete the plane wing and turn the vertical into a horizontal. Now it just looks like one of those vintage, turn-of-the-century postcards with lovely late August farms. Or a quilt patch.

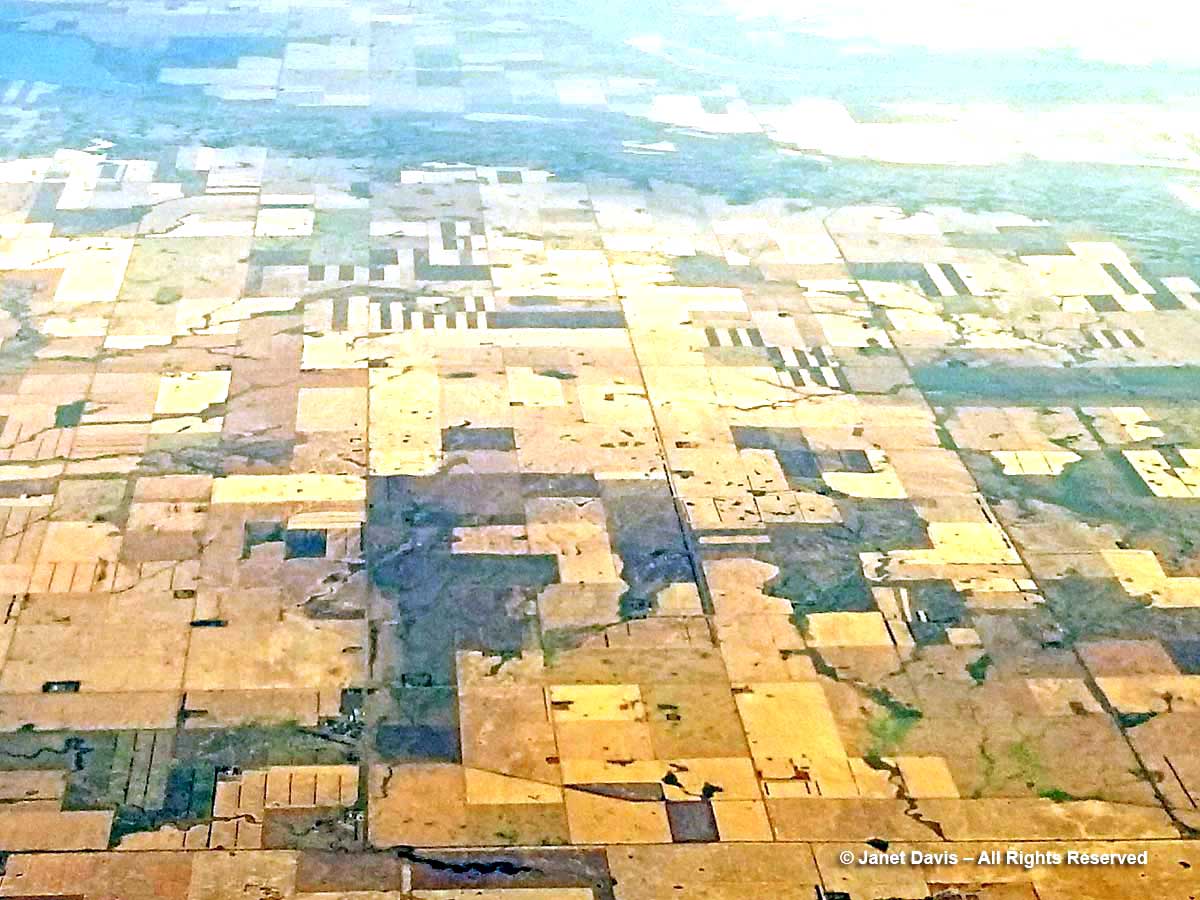

10:12 am – But where on earth am I? Somewhere in northern Minnesota or North Dakota, I think. There’s that little town cluster of buildings with the unique rectangular fields to the right. It seems to be a place that has some crops already harvested and the soil plowed (grayish fields) and other fields with lots of grain still to be cut. The green patches might be winter wheat or alfalfa crops sown to enrich the soil.

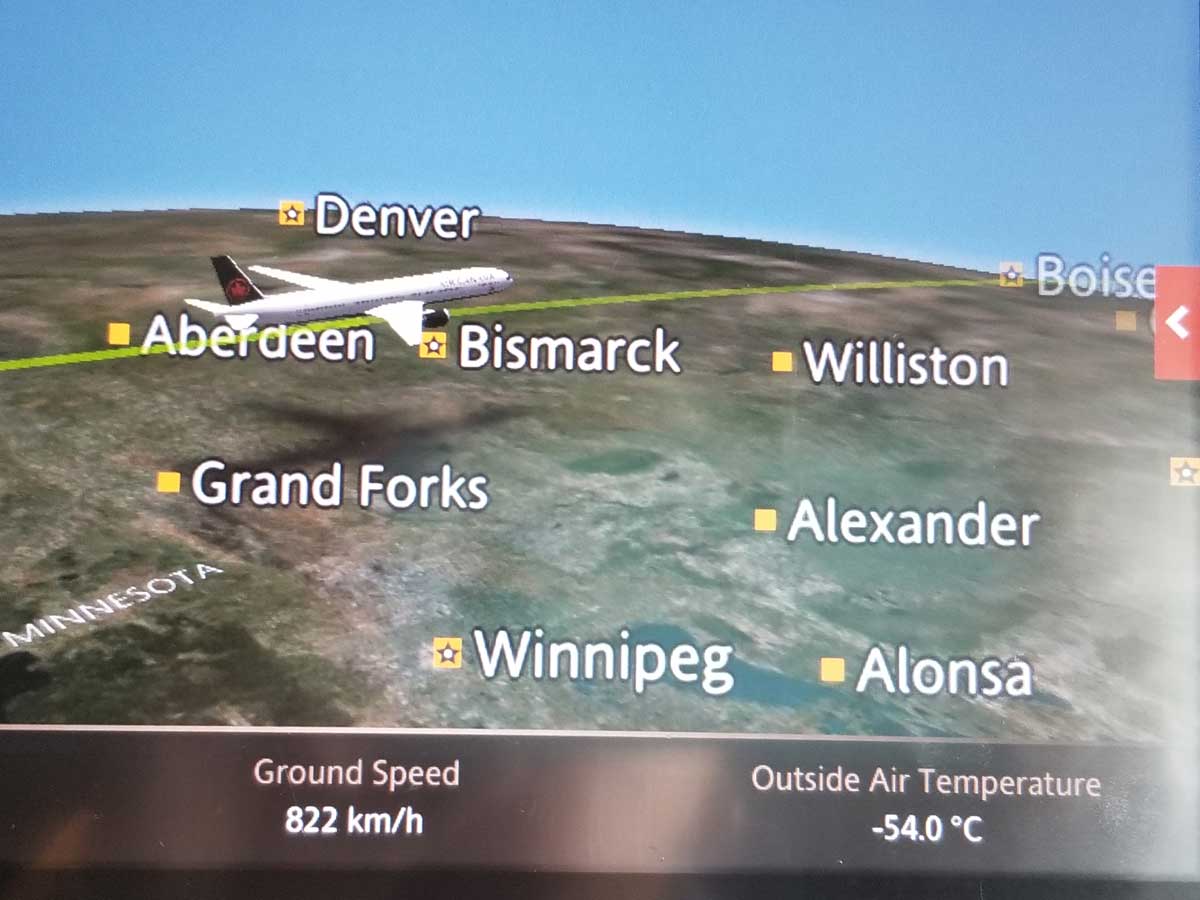

10:16 am – Minutes later, it occurs to me that there’s a way to figure out approximately where the plane is. So I begin to snap a quick shot of the Moving Map feature on the entertainment console in front of me after each out-the-window photo. It gives the rough coordinates, the time, the kilometres travelled and still to travel, the altitude and the airspeed. It isn’t exact GPS by any stretch, but it will be a useful guide later. And the identifications below are thanks in part to that guide, but especially to wonderful Google Earth, where you’re looking down on the actual forests, rivers and farms that you can see from the plane. (Any errors are mine, not Google Earth’s.)

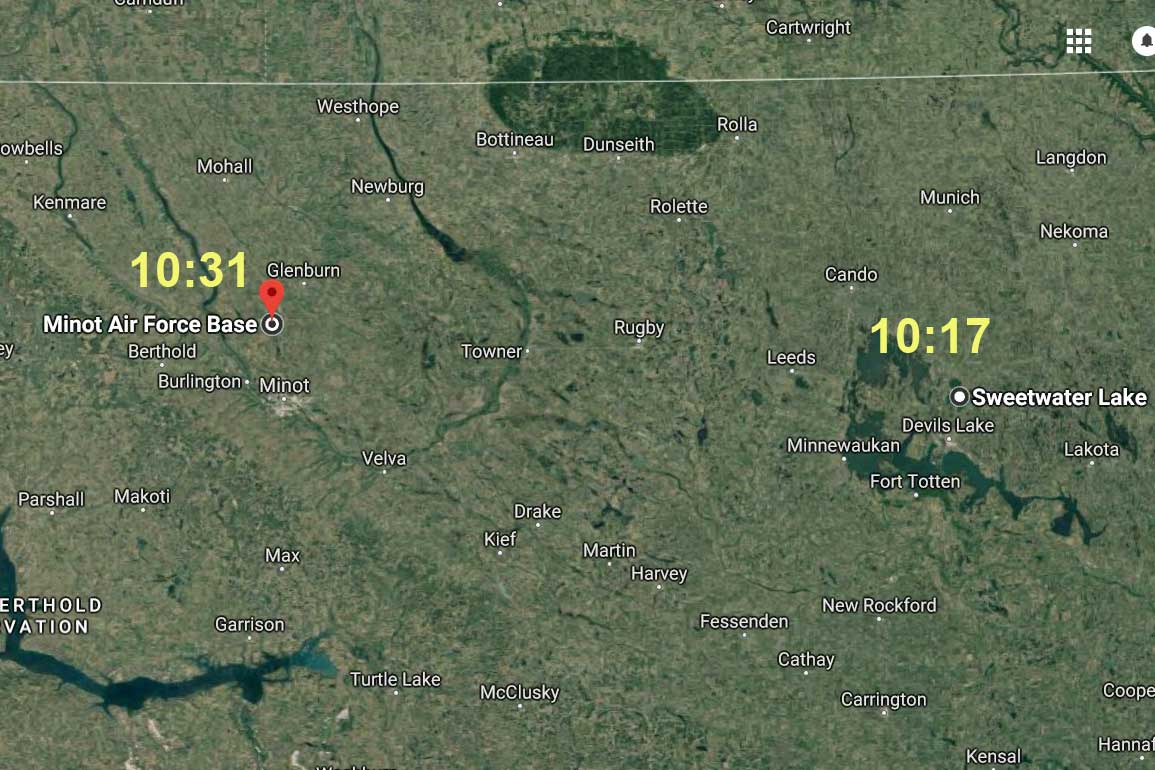

10:17 am – The late summer fields are resplendently golden around Morrison and Sweetwater Lakes in North Dakota.

And this is how I saw those lakes on Google Earth later (with a lot of squinty searching…)

10:18 am – Lakes in North Dakota are often named after people. Here we have Lake Alice, Mike’s Lake and Dry Lake at right, which already seems to be drying up.

10:20 am – Highway 2 leads toward Church’s Ferry on Lake Irvine, right. I’ve always wanted to go to North Dakota and this is a fun way to see it.

10:31 am – That runway, below, is a big clue to Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota.

Later, as I look for the locations on the photos, I discover various ways to plot the pilot’s route. One is to take two places you’ve already identified and draw a straight line between them, as I can now do with Sweetwater Lake and Minot Air Force Base. That should be the pilot’s general route and help with the rest of the photos.

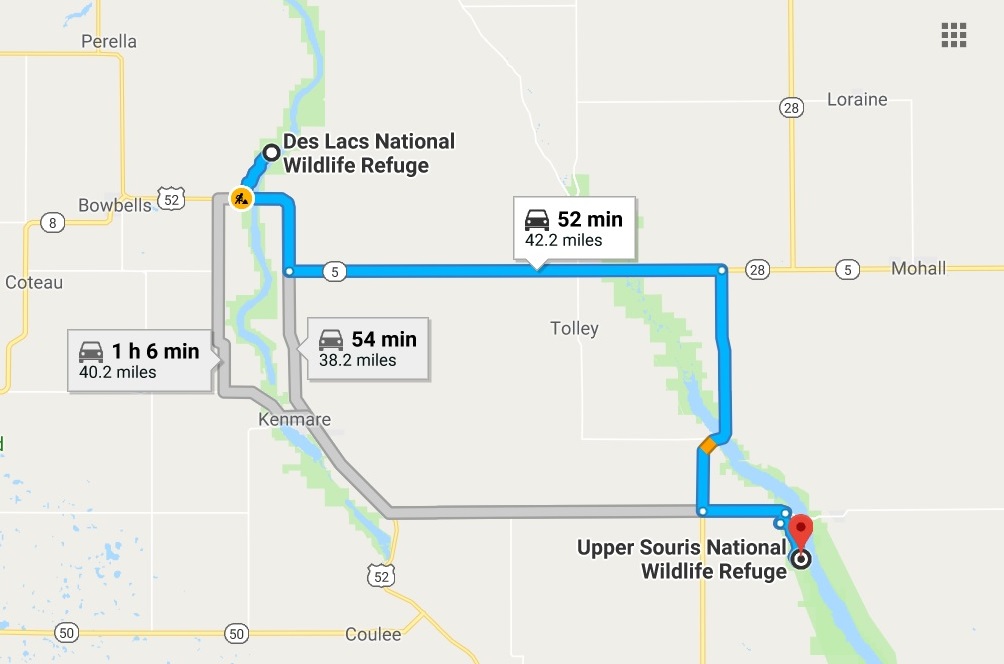

10:32 am – A lake trickles forward in a narrow, sinous stream through a valley that looks like varicose veins. Why it’s the Lake Darling Dam, the Souris River and the Upper Souris National Wildlife Refuge. (Later, I discover it’s named for Jay “Ding” Darling, the eminent naturalist I wrote about in my blog on a wildlife-friendly garden in Austin, Texas.)

10:33 am – Not far away (at least at 800 kilometres or 500 miles an hour) is another beautiful natural site: the Des Lacs National Wildlife Refuge. Here’s what I see by zooming the phone in.

10:34 am – And this is what I see as the plane moves west, along with the Upper Des Lacs River above it. Imagine TWO wildlife refuges to accommodate the migratory birds that stop in North Dakota on their way south and north!

Using Google, I learn later that the actual driving distance from one refuge to another is 52 minutes, using Highway 5.

10:43 am – I’m fascinated by the vast number of farm ponds in this part of North Dakota, below, unlike any other part of this journey over the Central Plains. I later learn, courtesy of my geologist friend Andy Fyon, that these are called prairie potholes. But that is an actual geographic designation, according to Wikipedia: “The Prairie Pothole Region is an expansive area of the northern Great Plains that contains thousands of shallow wetlands known as potholes. These potholes are the result of glaciaer activity in the Wisconsin glaciation, which ended about 10,000 years ago. The decaying ice sheet left behind depressions formed by the uneven deposition of till in ground moraines. These depressions are called potholes, glacial potholes, kettles or kettle lakes. They fill with water in the spring, creating wetlands, which range in duration from temporary to semi-permanent. The region covers an area of abouat 800,000 sq. km and expands across three Canadian provinces, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Alberta and five U.S. states, Minnesota Iowa, North and South Dakota and Montana.”

10:45 am – What’s this? White lakes? Why, yes! These are the saline lakes that extend from western North Dakota near Montana up into Saskatchewan. Their brine is also the source of Glauber salt or natural mirabilite crystals, which is used in making Kraft paper. This is Divide County, which means that it sits astride the Continental Divide, where rivers flower either east towards the Atlantic or west towards the Pacific, depending on which side of the divide they’re located.

10:46 am – The green lake, Miller Lake, is a little deeper and has not yet dried up except at the edges, exposing the salt residue. I love the round fields here, designed this way for centre-pivot irrigation. (See what you learn when you look out a plane window?) Montana is in the upper left of the photo.

10:46 am – Closeup of Miller Lake. (When I was a child living in British Columbia and we went on our summer vacation to my grandparents’ house in Saskatoon, my parents took my brother and me to one of Saskatchewan’s many salt lakes, Lake Manitou, near Watrous. The hilarious thing for kids was that we could not stand up in the water but we could not sink either, because the hypersaline concentration made us buoyant! These days it’s a mineral spa.)

10:53 am – Seven minutes later, we’ve crossed over the international border and we’re flying over the southwest Saskatchewan municipality of Hart Butte No. 11.

10:55 am – I’m unable to pinpoint the exact location below, but I love the striped fields and am delighted to discover that they’re just the result of the way the farmer plows, not that he sowed dark and light crops in rows! City slickers…..

10:56 – The big rocky chunk below is Poplar Valley, Saskatchewan, with Fife Lake in the upper left.

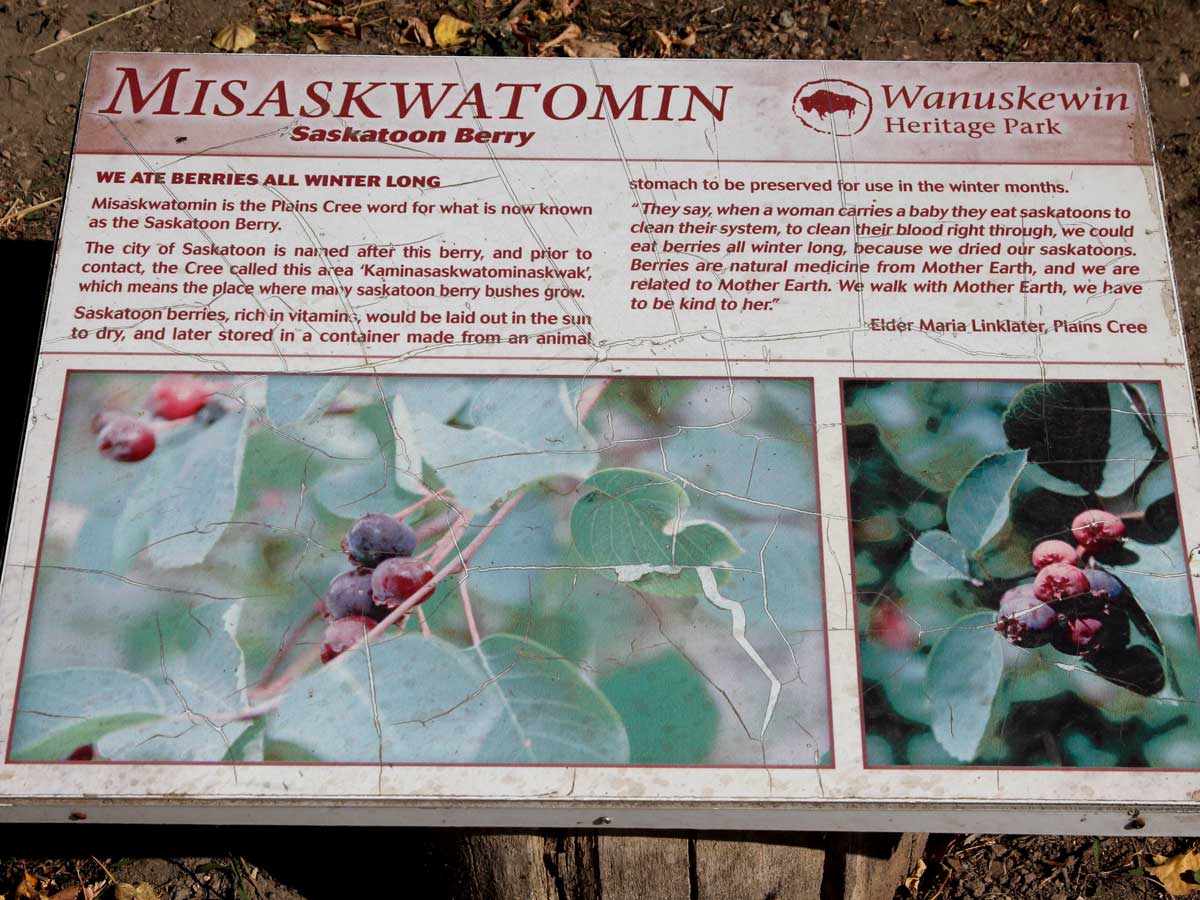

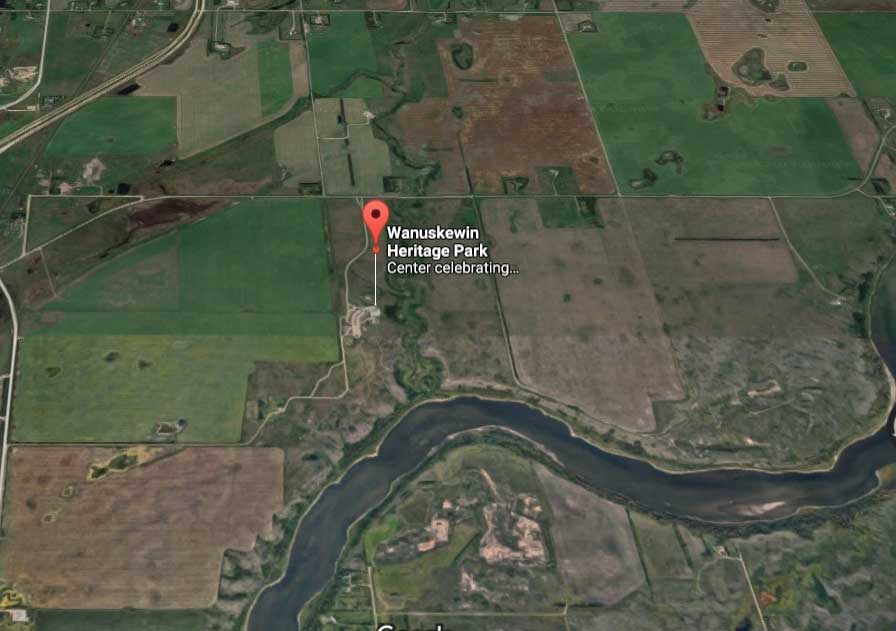

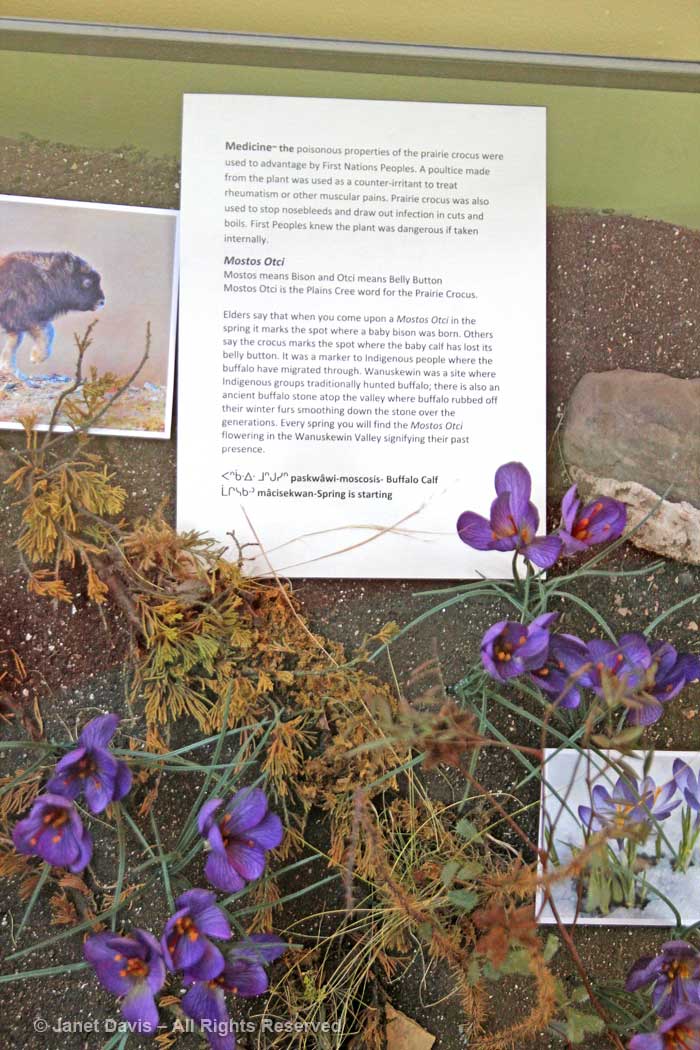

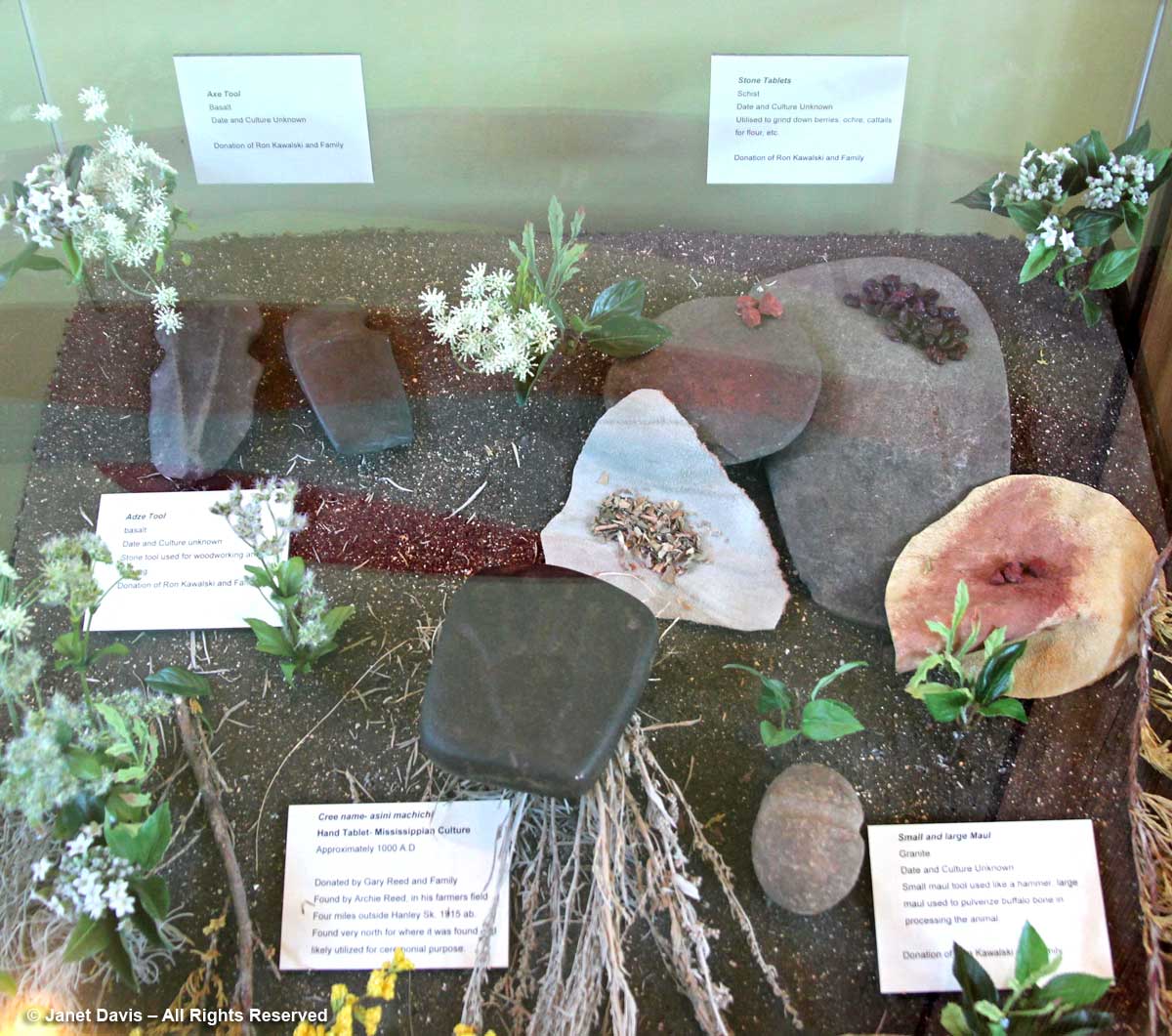

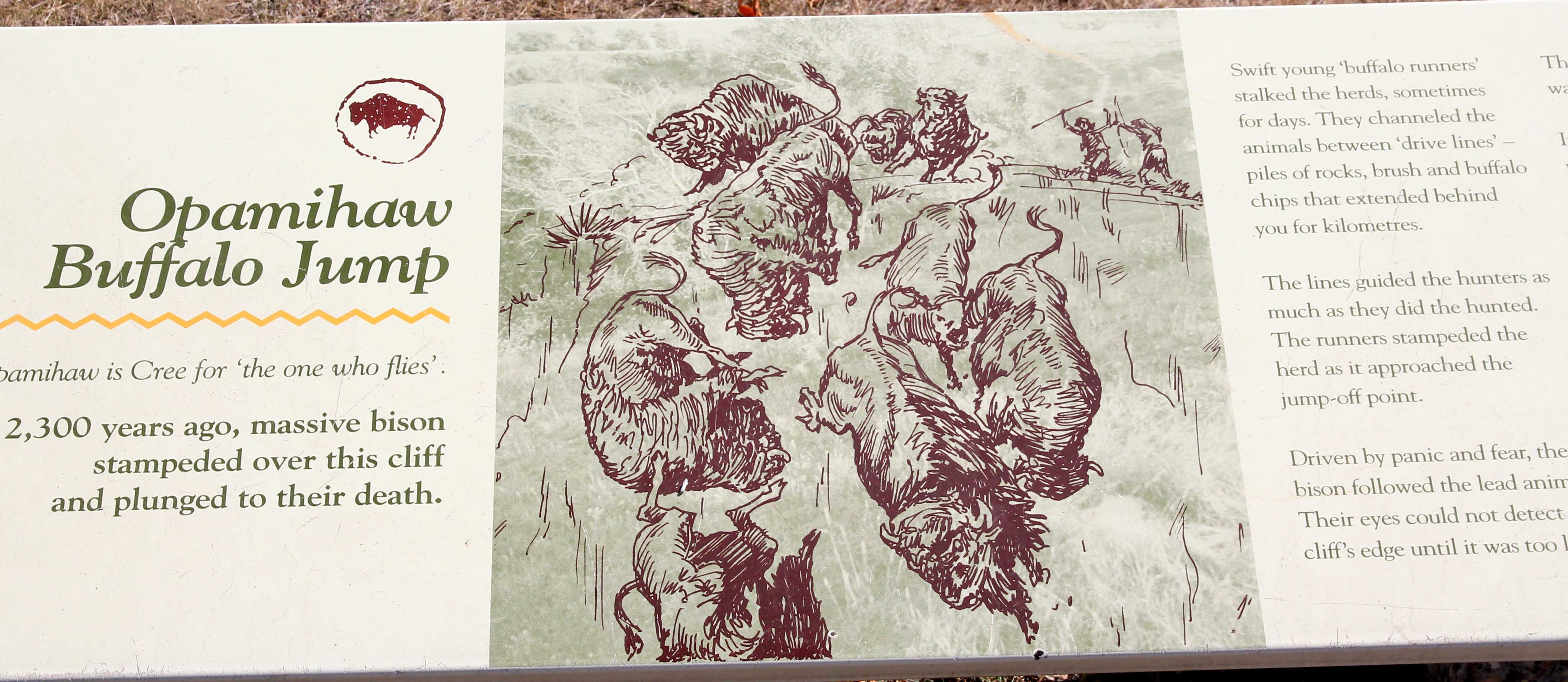

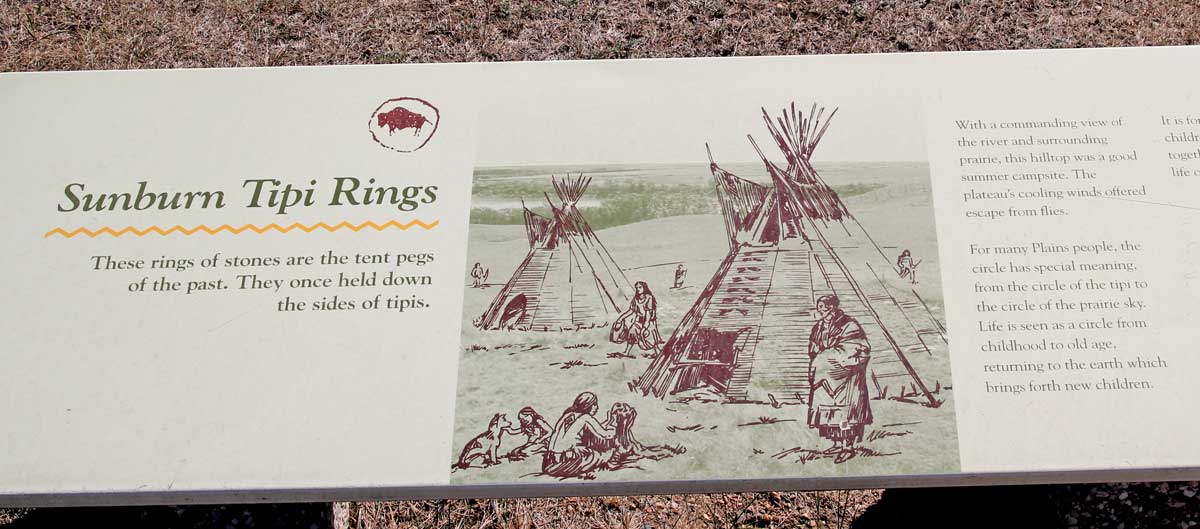

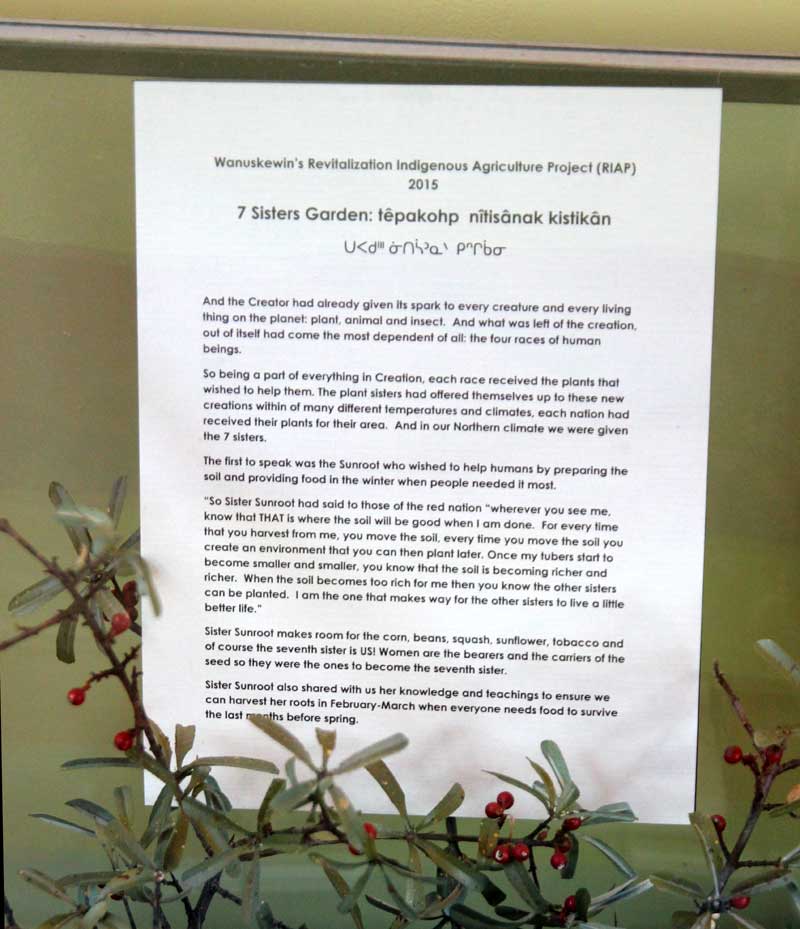

11:01 – Prairie topography is not all pancake-flat, of course, and the view below shows the delicious tentacles of prairie valleys near Wood Mountain Provincial Park (there’s actually a little mountain there.) This region has a fascinating history. In 1876, following his defeat of General Custer at Little Bighorn, Sitting Bull and 5,000 of his Lakota Sioux followers took refuge here, resulting in negotiations with the North West Mounted Police who gave them shelter provided they obeyed Canadian laws. In time, many died and many more left, including Sitting Bull, who headed to Wyoming in 1885 and joined Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show. Last autumn, after visiting and blogging about Wanuskewin near Saskatoon, where I was born, I read the gripping accounts of those long-ago days in Wallace Stegner’s delightful book Wolf Willow, which I highly recommend to lovers of all-things-prairie. From 1917 to 1921 he was a young boy in Eastend, Saskatchewan (which he fictionalized in the book as Whitemud) when his parents tried to make a farm living there. His memoir-history-novelette brings the region to vivid life!

11:07 – Speaking of Eastend, this is the long Frenchman River Valley just west of the town. On the north side around the middle is Jones Peak, which gives a commanding view of the area, including the new T.Rex Discovery Centre, home to Scotty, the world’s biggest tyrannosaurus! It’s also the repository for fossils from the Frenchman River Valley and the nearby Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park.

11:24 – After reading Stegner, one of my aims in life is to get to Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park – 2,500 square kilometres of prairie (fescue grassland, dry, mixed grass prairie) that reaches across the provincial border into Alberta. (Maybe combined with a trip to Alberta’s fossil-rich Badlands.) I caught a little section of the park below.

11:32 – Taber, Alberta isn’t very big, but I managed to find it, along with winding Old Man River, the Horsefly Lake Reservoir and Taber Lake.

I have a funny little story about Taber. They grow sugar beets there. How do I know? Because when we were kids on one of those interminable summer car trips to Saskatoon from Vancouver (or Victoria before that), my dad stopped for gas at a station. It wasn’t open but the big tanker truck was filling up the tanks and the guy offered to give us some gas. After we headed down the highway, our little 1949 Austin of England sputtered to a stop. It wasn’t until dad hitchhiked into Taber, leaving four of us sitting in a hot little car beside a sugar beet field, and returned with the tow truck to haul us into a service station, that we learned that the tanker truck had filled our little car with diesel fuel, not gasoline. This is that car a few weeks later, camping gear on the roof, set for the 3-day return trip, with grandpa and me in his vegetable garden and my uncle and cousin standing behind to say goodbye. What great summer vacations those were.

11:35 – Three minutes after Taber, we fly over the town of Coaldale, Alberta on the Crowsnest Highway. Though coal wasn’t mined there (it was named after its wealthy first resident’s family estate in Scotland), the fact that a station was built there on the brand-new Canadian Pacific Railway line resulted in it becoming a service town in prime, wheat-growing territory in southern Alberta. In fact, Coaldale become known as the “gem of the west” for its wheat. (Which reminds me of another family story. My elderly Aunt Rose, a maiden great aunt living north of Saskatoon in Elrose, Saskatchewan grew wheat on her property as well. In those boom days for grain, her relatives in B.C. knew the “Russians were buying wheat” when she included a crisp $20 bill in her Christmas card.)

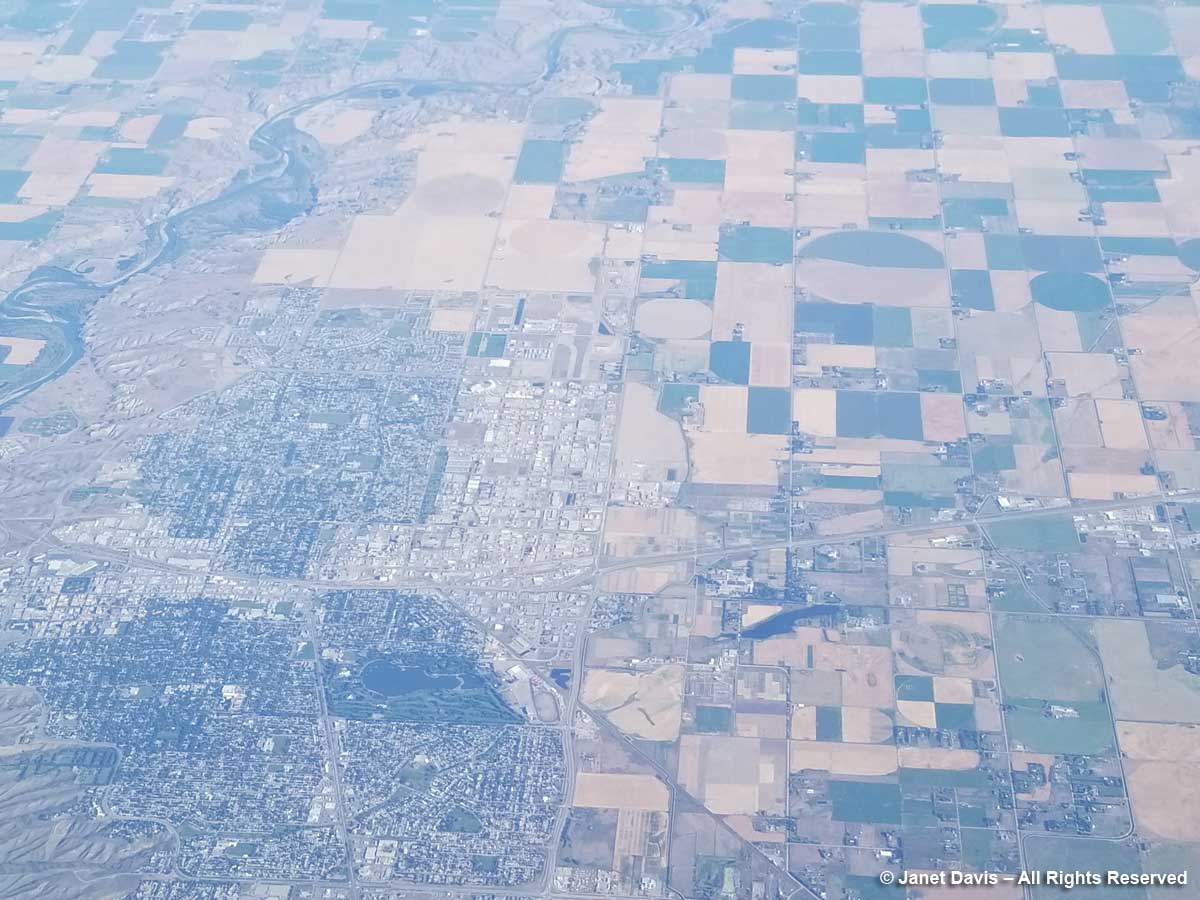

11:36 – For photo-editing comparison, I include the image below of Lethbridge, to illustrate the appearance of the images straight out of the Samsung 8.

11:36 – And now here’s Lethbridge with some help from Photoshop. The largest city in southern Alberta, it’s the fourth largest in the province after Calgary, Edmonton and Red Deer.

11:40 – That white patch below is Mud Lake, just a little west of the town of Fort MacLeod, out of the picture on the right. And that grey patch to the left is the start of the Rocky Mountain foothills.

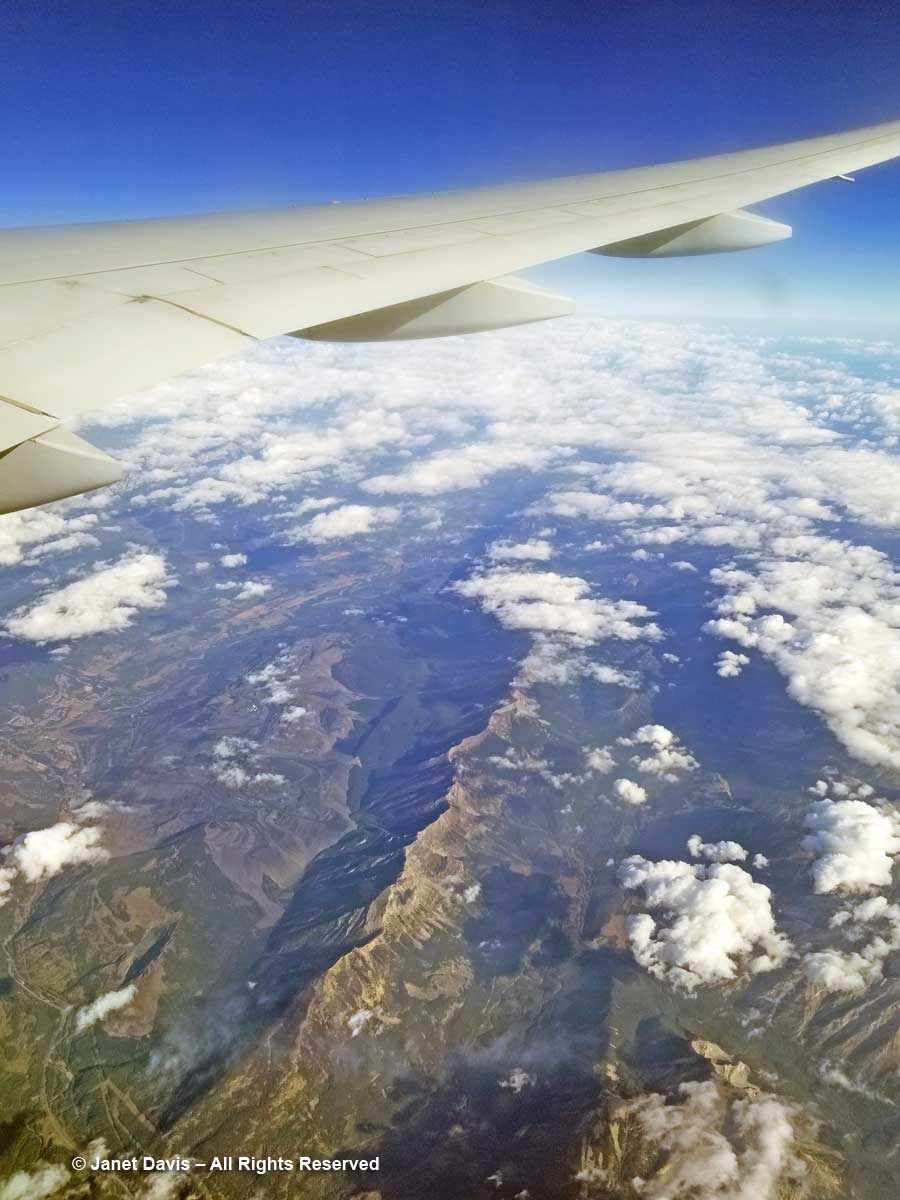

11:47 – Seven minutes later, we’re flying over /Alberta’s Rocky Mountains heading into British Columbia.

11:51 – This part of the Rockies in southeastern British Columbia is referred to as the Kootenays, after the Kootenay River, which is in turn named for the Kutenai First Nations. In previous spring trips when I glanced out the window, the mountains were covered with snow. Now I see the jutting grey rock and the fuzzy green of the treeline below.

11:51 – Puffy clouds hang over the mountains but visibility is still very clear.

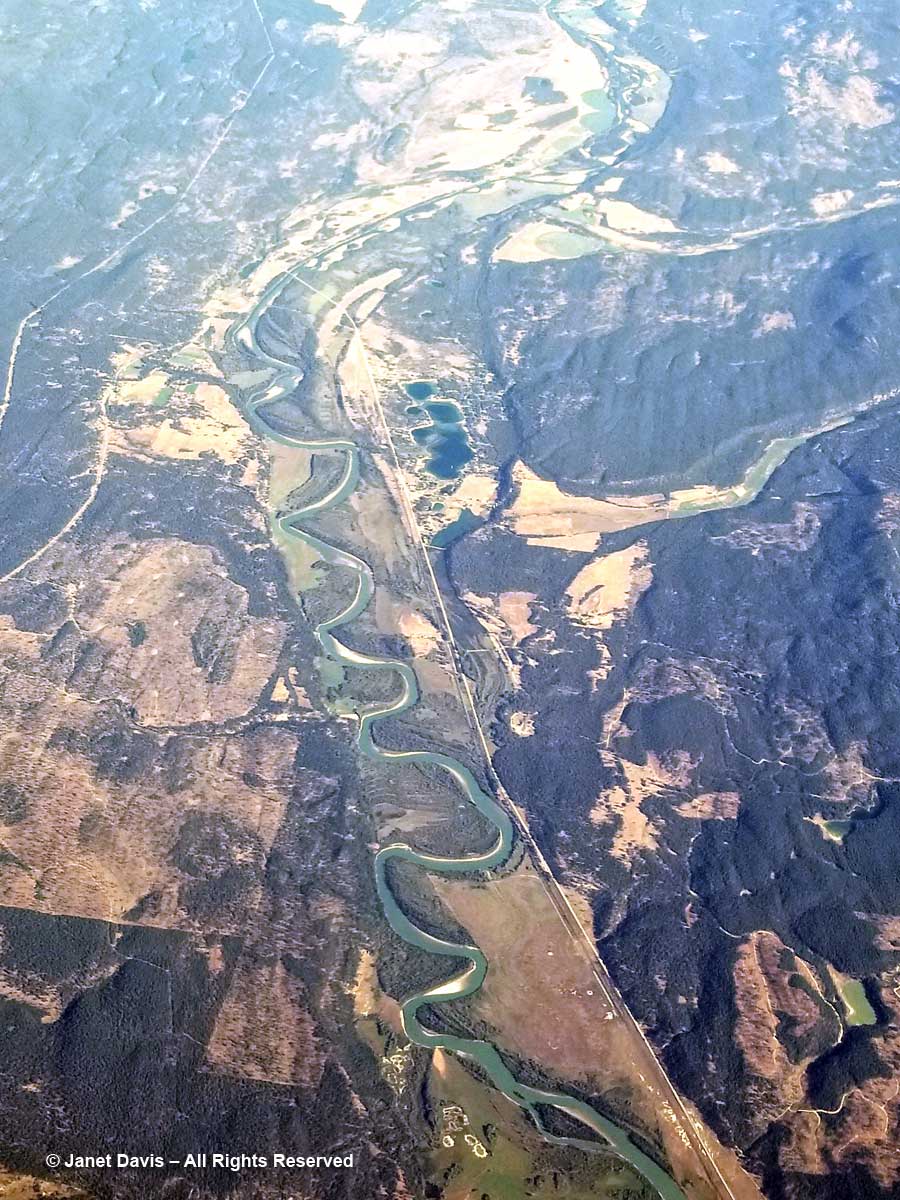

11:53 – The Kootenay River winds along the valley bottom and eventually empties south into Lake Koocanusa – an acronym of Kootenay-Canada-USA, since the lake spans the border. These mountains are the headwaters of the river, which flows through Montana and Idaho and back into British Columbia where it joins the Columbia River.

12:01 – Looking out the airplane window, it occurs to me that air flight entertainment could potentially offer much more than just second-run movies and network news. This map feature could offer geography and geology lessons in real time. Reading John McPhee’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning opus ‘Annals of the Former World’ earlier this summer, I read about the Laramide Orogeny (named for Laramie, Wyoming), the mountain-building process that saw the Farallon Plate in the Pacific shove itself under the Continental plate and give rise 80-55 million years ago to the Rocky Mountains, this backbone of jutting granite peaks reaching from Canada into Mexico. As Wikipedia states: “The current Rocky Mountains arose in the Laramide orogeny from between 80 and 55 Ma. For the Canadian Rockies, the mountain building is analogous to pushing a rug on a hardwood floor: the rug bunches up and forms wrinkles (mountains). In Canada, the terranes and subduction are the foot pushing the rug, the ancestral rocks are the rug, and the Canadian Shield in the middle of the continent is the hardwood floor.”

12:12 – That bridge across long Okanagan Lake is a clue that this is Kelowna below.

12:13 – The little towns below flanking Okanagan Lake are B.C.’s prime fruit-growing and vacationing region – an area we simply called “the Okanagan”.

12:14 – Okanagan Lake is 135 km (86 miles) long, with a maximum depth of 232 metres (761 feet). It’s classified as a “fjord lake” because it was carved out by repeated glaciations.

12:15 – Unsurprisingly, clouds roll in as we fly over the mountains on the far side of the Okanagan valley, obscuring some of the most beautiful scenery in North America.

12:35 – The clouds clear in time for me to see the busy Burrard Inlet and port of North Vancouver below.

12:36 – A minute later, through small breaks in the cloud and raindrops on the window, I can just make out Lion’s Gate Bridge spanning from the north shore to Stanley Park in the bottom middle. The captain has now raised the spoilers to slow the plane and prepare to begin his wide turn over the Strait of Georgia, the arm of the Pacific Ocean between Vancouver Island and the British Columbia mainland.

12:37 – I see a circle of freighters at anchor in English Bay. For a few years back in the mid-1970s, this bay and its weekend sailboat races were my view when I lived in my little condominium up the hill in nearby Kitsilano.

12:41 – More clouds over the ocean. We’re flying blind. Fortunately the captain has instruments.

12:42 – Out of the clouds now and I see a freighter outward bound into the Pacific.

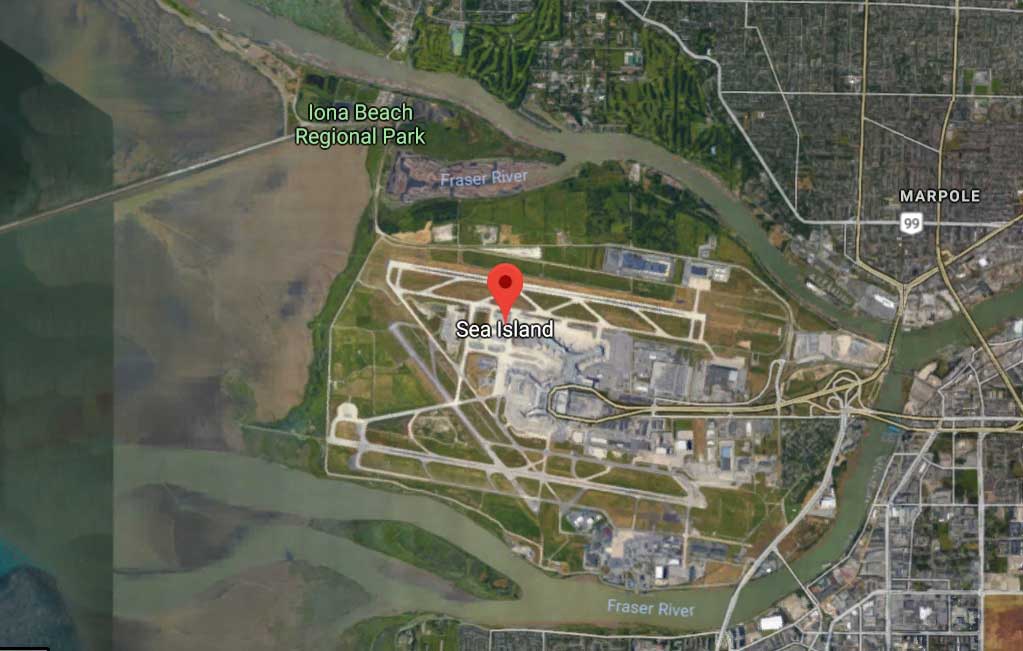

12:45 – Vancouver International Airport is located on Sea Island and these marshes at the runway perimeter are on the ocean.

Sea Island sits between the north and south arms of the mighty Fraser River as it empties into the sea after its 1375 km (854 mile) journey from far up in the Rocky Mountains.

12:46 – On the tarmac and taxiing towards our arrival gate. I calculate that I’ve been photographing out the window at Seat 45K for more than three hours. And having chronicled the journey, I feel that I know a little more about this beautiful old planet than I did when I put my seat belt on in Toronto. Much more.