Before the bloom is off the rose, I’d like to take you on a tour of the Idaho Botanical Garden. This has been sitting in my to-do pile for a year, the delightful culmination of a trip we made to the Grand Tetons, Yellowstone National Park and Sun Valley, Idaho last September. That morning, we’d driven down from Sun Valley, elevation 5945 feet, with its ski runs visible, below…..

….to Boise, 2730 feet.The late summer scenery on the 160-mile drive down was at first sage-dominated high rangeland (ecologically termed “sagebrush steppe”) flanking the Sawtooth National Forest….

….and later, as we descended towards Highway 84 near Mountain Home, Idaho, gold and green farm grasses and picturesque grain silos against a backdrop of the indigo-shaded mountains of the Sawtooth Range.

How I would love to have been on this road in spring – an entire camas prairie!

After making the turn onto Highway 84, we headed northwest into Boise where I had arranged to meet my garden writing colleague Mary Ann Newcomer, author and host of Dirt Diva on Boise radio. (If you’ve got a few minutes, listen to this excellent interview with her on North State Public Radio.) She kindly picked us up at our hotel after lunch and chauffeured us to the botanical garden where she spent 10 years as a board member and continues her relationship today as the garden updates certain sections.

We entered via the newly-installed, Franz Witte-designed Entrance Garden.

Coming in we passed a display of annuals that was as beautifully-maintained as it was colourful!

There was a wedding reception going on in the English garden when we arrived, but we asked permission to sneak in.

Mary Ann continues to be particularly involved in the English garden, now undergoing a design update to accommodate the increased shade of trees that were tiny sticks when installed years ago, like the lovely katsura (Cercidiphyllum japonicum) below…

I liked the unobtrusive shrub support for this clematis.

Iron gates created a lovely flow through this garden.

Late summer perennials, shrubs and grasses were in their glory, like the blue mist bush (Caryopteris x clandonensis) with feather reed grass (Calamagrostis x acutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’) below.

There were some sweet surprises, too, like this miniature pumpkin vine climbing the upright stems of fernleaf elderberry (Sambucus canadensis ‘Laciniata’).

We were chatting so much, I didn’t pay close attention to our meander into other areas, including the Rose Garden. Looking up through rose blossoms at a former prison watchtower, this is when you understand that the Idaho Botanical Garden is situated on the former site of the Idaho Penitentiary. And though all the buildings now house botanical garden administration offices, etc., it’s a remarkable use of historic property.

We passed some fun metal sculptures.

I loved this little inset border of colourful annuals beside the Meditation Garden.

In the Children’s Garden was a fabulous display of carnivorous plants. What a great teaching opportunity this is. (And yes, that’s native annual sunflower behind!)

And this looked like great fun for kids.

For this high desert climate (Boise is classified as USDA Zone 7, but frequent, sustained winter lows have persuaded Mary Ann that it’s safer to buy plants for Zone 5), Idaho Botanical Garden features an important garden, the Plant Select® Demonstration Garden. Based on a program developed by Denver Botanic Garden and Colorado State University, these are plants that are adapted to Boise’s hot, dry summers. I loved this combination of Bouteloua gracilis ‘Blonde Ambition’ and Wright’s buckwheat (Eriogonum wrightii var. wrightii).

And this little firecracker has become a new “it” plant: ‘Marian Sampson’ hummingbird mint (Monardella macrantha).

What about this gorgeous Mojave sage, Salvia pachyphylla?

As we left the Plant Select® garden, I stopped to admire a little sagebrush lizard.

We passed by the beautiful Herb Garden….

…. but stopped for a bit in the Vegetable Garden.

Check out the cages on those berries! That’s the way to outsmart birds and rodents.

You can grow grapes in the high desert!

Then it was on to the Summer Succulent Garden.

I could have spent a lot of time studying the various opuntias and cylindropuntias…..

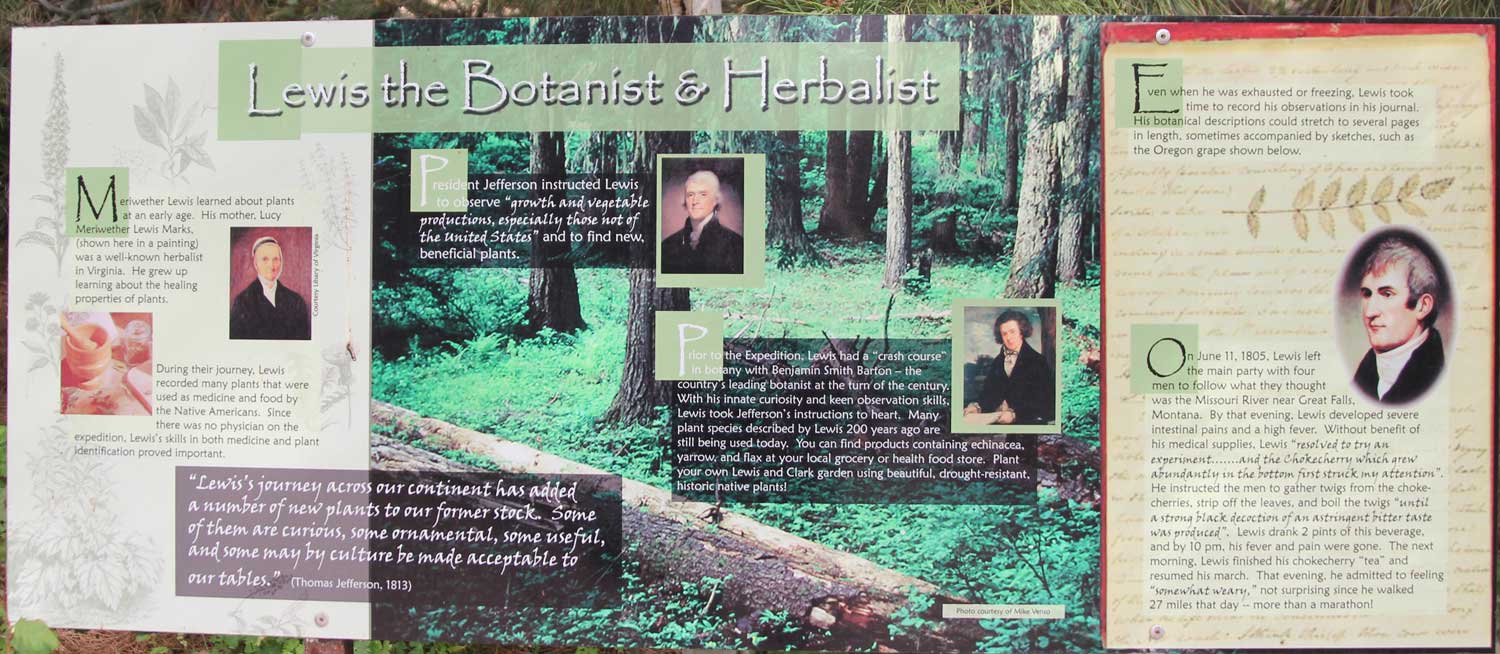

But we were heading up to another of Mary Ann’s favourite areas: the Lewis & Clark Native Garden. The garden celebrates a score of native plants, including many that were recorded for the first time by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and their Corps of Discovery during their President Thomas Jefferson-commissioned 1803-05 expedition west through the Louisiana Territory to the Pacific.

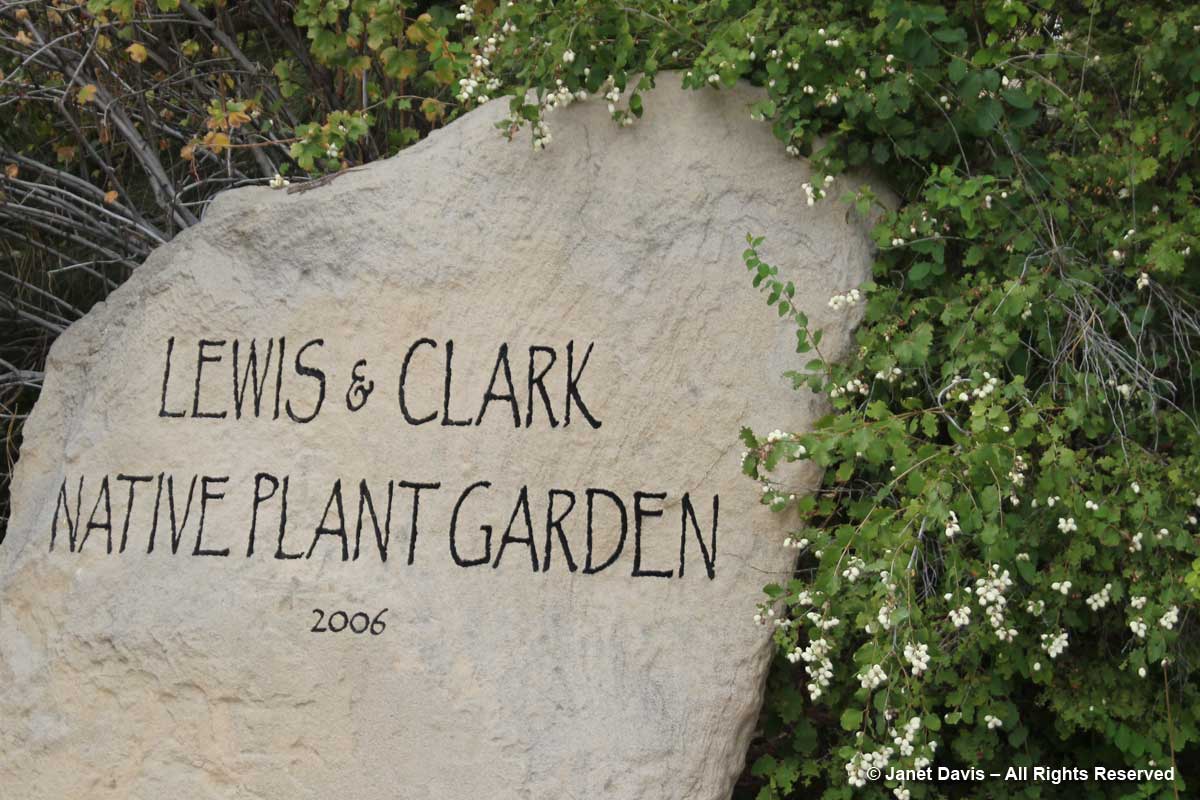

For me, this fabulous garden represents what botanical gardens should be doing everywhere: celebrating locally indigenous plants according to their geographical and ecological niches, and showing visitors the rich diversity of flora native to their region. Here the stone marker is appropriately flanked with snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus), a plant observed by Lewis near Missoula, Montana on August 13, 1805.

I saw plants I’d never heard of before on this path, like fernbush (Chamaebatiaria millefolium), with its big, bee-friendly panicles……

….. and cascara buckthorn (Rhamnus purshiana), whose dried bark was used as a laxative by the Native Americans of the Pacific northwest, then by colonialists. (I even recall cascara being in medicine cabinets when I was a girl!)

In the Western Waterwise Garden…..

….. I found beautiful creeping hummingbird trumpet (Zauschneria garrettii ‘Orange Carpet’)….

In the Wetlands Garden….

…. there was familiar Oregon grape (Mahonia aquifolium)….

…. and unfamiliar black or Douglas hawthorn (Crataegus douglasii), ultimately named for David Douglas, who later collected the seed in his explorations of the west….

…. and lovely streambank wild hollyhock (Iliamnia rivularis).

Then I was exploring Plants of the Canyons. I loved this creative way of showing off Idaho natives!

Beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax) was collected by Lewis & Clark on June 15, 1806, on the Lolo Trail in Idaho’s Bitterroot Mountains. Clearly, young plants are a favourite of hungry herbivores up here!

Here is beautiful western columbine (Aquilegia formosa), recorded by the explorers the very next day, June 16th.

Nine days later, on June 25, 1806, they found scarlet gilia (Ipomopsis aggregata) on the Lolo Trail.

Look at the beautiful markings of scarlet gilia, which show stripes typical of the colour shift that occurs in some populations of this species later in the season. According to the USDA: “Red-flowered races of scarlet gilia tend to be pollinated mostly by hummingbirds, which are especially attracted to the color red because of their outstanding vision. White flowers are more attractive to moths that visit the gilia flowers at dusk or nighttime and are drawn by the flower’s unpleasant scent. Scarlet gilia blooms over much of the summer and in some populations blossoms that emerge from May to July are red and hummingbird pollinated, while flowers that mature later in July and August are white and pollinated by moths. This color shift can even be observed among different flowers on the same plant.”

To treat his fever and intestinal condition, Lewis made a dark tea of chokecherry bark (Prunus virginiana), shown in fruit below, collected May 29, 1806 near present day Kamiah, Idaho.

Oceanspray (Holodiscus discolor) was noted on the same day.

Nootka rose (R. nutkana) had already formed hips. It was observed in flower on the Wieppe Prairie by Lewis & Clark on June 10, 1806.

In the grasses grew annual sunflower (Helianthus annuus), so elegant and simple – unlike the big, multi-coloured forms produced by hybridizers over the past two centuries. Its height was impressive to Sgt. John Ordway, who referred to it as “weedy” on August 13, 1804. He wrote: “we crossed the North branch and proceded along the South branch which was verry fatigueing for the high Grass Sunflowers & thistles &C all of which were above 10 feet high”

Annual great blanketflower (Gaillardia aristata) was observed by the expedition in what is now Lewis & Clark County (Helena), Montana, on July 7, 1806.

On February 2, 1806, the Lewis & Clark expedition was at Fort Clatsop, Oregon, when blue elderberry (Sambucus nigra ssp. cerulea) was collected.

Prickly pear (Opuntia polyacantha) was observed on September 19, 1804 in Lower Butte, South Dakota, but its effects were regularly felt by the Corps of Discovery. Wrote Clark: “… as the thorns very readily perce the foot through the Mockerson; they are so numerous that it requires one half the traveler’s attention to avoid them.”

Ponderosa pine, of course, is the predominant conifer in this region. When Clark was preparing to navigate the Columbia River in the fall of 1805 and his men were ill and weak, he felled ponderosas and hollowed them out by burning so they could serve as canoes. The seeds are edible, and the pitch from the tree could be used to waterproof the canoes, but it was also used as chewing gum and as a glue to fix arrowheads to the shafts.

I finally reached the top and saw a small garden devoted to Sacajawea (c. 1787-1812). As a child in the Shoshone nation, she had been kidnapped and raised by the Haditsa tribe before being sold in 1804 to French-Canadian fur trapper Toussaint Charbonneau. However unsavory her husband (nine years earlier, he had been stabbed by an old Saultier woman in Manitoba for raping her daughter, and he was already married to a Shoshone when he married Sacajawea), Clark valued Sacajawea immensely for her knowledge of the Shoshone language and arranged for her, Charbonneau (who spoke Haditsa) and his other wife, Otter Woman, to accompany the expedition as translators. In February 1805, Sacajawea’s son Jean Baptiste was born on the trail.

Not only did Sacajawea find food for the expedition from the land, including hog peanuts (Amphicarpa bracteata) and Indian breadroot (Pediomelum esculentum), she provided valuable information on the navigability of the Missouri River, in Montana, having recognized it from her childhood with the Shoshone. On August 17, 1805, Clark watched as she was reunited with her brother Cameahwait, the Shoshone chief. She and Otter woman then translated communications from the Shoshone to the Haditsa language, which Charbonneau was then able to translate into English for Clark and Lewis. After the gruelling 3-week trek through the Bitterroot Mountains they finally reached a tributary of the Columbia River. The painting below by famed Montana artist Charles Marian Russell was made in 1905, exactly 100 years later, titled “Lewis & Clark on the Lower Columbia”, and shows Sacajawea gesturing to unidentified Indians of a West Coast tribe.

In early winter, Clark and Lewis reached the Pacific Ocean. When a trip was arranged to procure whale meat, Clark wrote of Sacajawea: “She observed that She had traveled a long way with us to See the great waters, and that now that monstrous fish was also to be Seen, She thought it verry hard that She Could not be permitted to See either (She had never yet been to the Ocian).” She and Charbonneau were allowed to go. They began the return trip in late spring, Jean Baptiste, and the Charbonneau family stayed with the expedition until August, 1806, when Clark offered to set them up in St. Louis and oversee the education of Jean Baptiste, whom he had nicknamed “Pompey”, his version of the Shoshone word for “firstborn”. Though Charbonneau refused initially, in September 1809 he bought land from Clark and tried his hand at farming for 18 months, before quitting and departing with Sacajawea, leaving behind their 5-year old son to be raised by Clark. Sacajawea would die of typhus a few years later, four months after giving birth to their daughter Lisette. Eventually, the guardianship of both children would be transferred to Clark.

It would have been wonderful to visit Sacajawea’s garden in spring, when the camas is in bloom.

As it was, I had to content myself with enjoying this sculpture by Rusty Talbot called Camas Lily/Sacajawea.

Standing at the Promontory, I was able to look down at the old prison buildings below through two more common sage steppe plants mentioned by Lewis & Clark, green rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus) with yellow flowers in the foreground, and rubber rabbitbrush or chamisa (Ericameria nauseosa) with glaucous leaves beyond.

I could have dallied for hours more, but it was time to make the trek back down. Thank you, Mary Ann Newcomer, for introducing me to your special garden. I learned so much!