I have been on safari in Africa; I’ve crossed the Andes and walked the streets of Paris, London, Rome, Athens, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Bangkok and Buenos Aires. But August 2nd was one of the most memorable and magical travel days in my life. It was a glorious morning as we awakened in Disko Bay off the central coast of West Greenland and gazed out at the massive icebergs littering the calm ocean surface. Disko Bay or Qeqertarsuup tunua in Greenlandic, is considered a southeastern inlet of Baffin Bay.

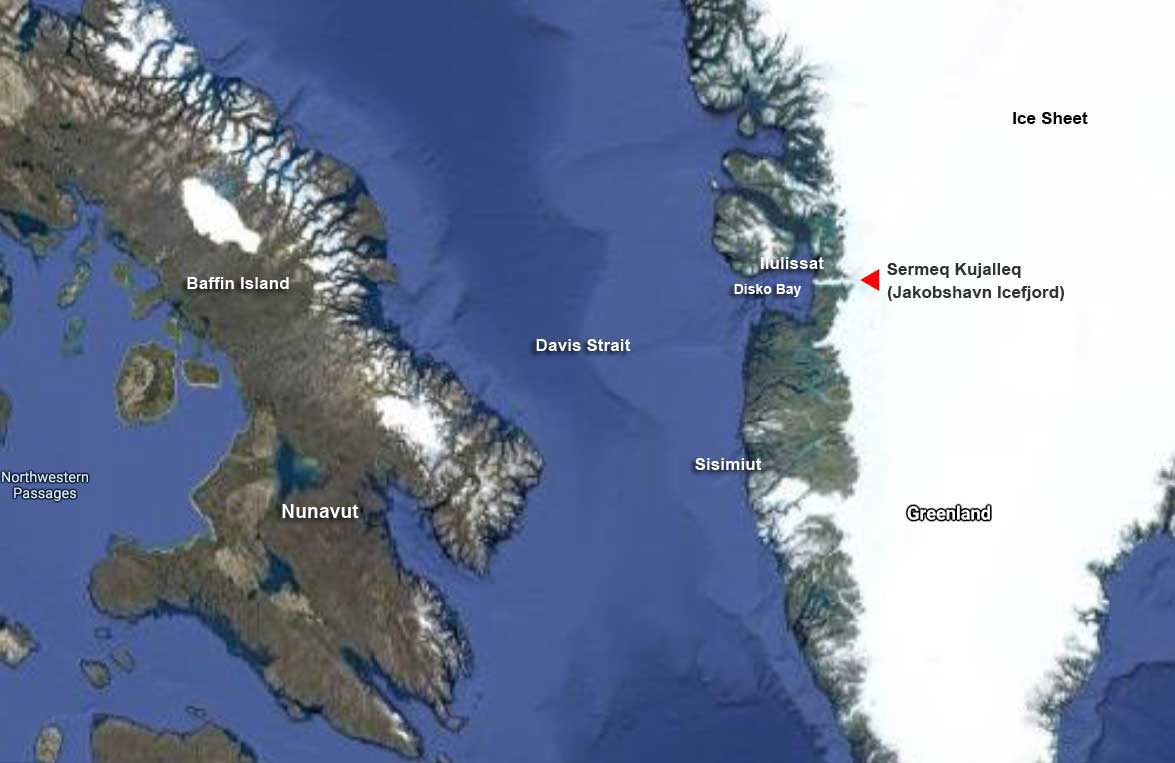

Overnight, we had sailed north from Sisimiut (which was the subject of my last blog) and navigated around Disko Island into this bay or “bugt”, as it’s called in Danish. That massive white expanse covering most of Greenland (the largest island in the world) on the Google Earth photo map below is ice, some 1.71 million km² or 660,000 square miles. Greenland’s ice sheet (also known as Inland Ice) covers 79% of the country and is second only to the Antarctic ice sheet, which is ten times as big. Together, Greenland and Antarctica contain almost three-quarters of the world’s fresh water. At its thickest point, Greenland’s ice sheet is 3 km (1.79 mi) thick with a volume estimated at 2.85 million km3 (684,000 mi3). Greenland has more than 100 glaciers (e.g. Kangerlussuaq, Helheim, Petermann, Hiawatha, Kong Oscar, Midgard) that flow out through its rocky margins each summer and send icebergs into the sea, but the Jakobshavn Icefjord or Isbrae (Danish) – Sermeq Kujalleq (Greenlandic) is the biggest, and the one we were here to see.

Fishboats were out in the bay, its waters rich in halibut, cod, Atlantic redfish, Arctic char and wolffish.

These guys just heading out were as curious about us as we were about them.

I loved the cheerful colours of this little fishing boat….

….. and the contented look of the fisherman about to head to work.

Turning towards shore, we saw the village of Ilulissat with its colourful houses arrayed up the rocky hillside under a massive mountain wall. (Greenland has myriad mountain ranges, many still unnamed). Established as a trading post by Danish merchant Jakob Severin in 1741, it was originally known as Jakobshavn. The third-largest city in Greenland after Nuuk and Sisimiut, Ilulissat has a population of 4,670 (2020).

Kalaallisut is the Greenlandic language of West Greenland (East Greenland has its own) and the Kalaallisut word for “icebergs” is Ilulissat! So there was no question why we were here; indeed, this is the town closest to the Ilulissat Icefjord UNESCO World Heritage Site that we were about to visit.

The hotel in the distance is one of three in town catering to tourists and scientists. In 2015, there were 22,000 international tourists and 15,000 local tourists, with the majority coming in July and August.

A plane passed overhead bringing passengers from Iceland as part of a seasonal schedule.

When Zion Church (Zion’s Kirke) was dedicated as a Lutheran church in 1779, it was the largest man-made building in Greenland. According to the Geological Survey of Denmark website, “During the Napoleonic Wars supplies from Denmark were limited, and the time from 1807 to 1814 in particular was a period of great hardship. In Jakobshavn, the hunters were forced to re-melt the lead from the roof and windows of the Zion Church in order to make rifle bullets.” It was moved to this location from lower ground in 1929, and services continue there today.

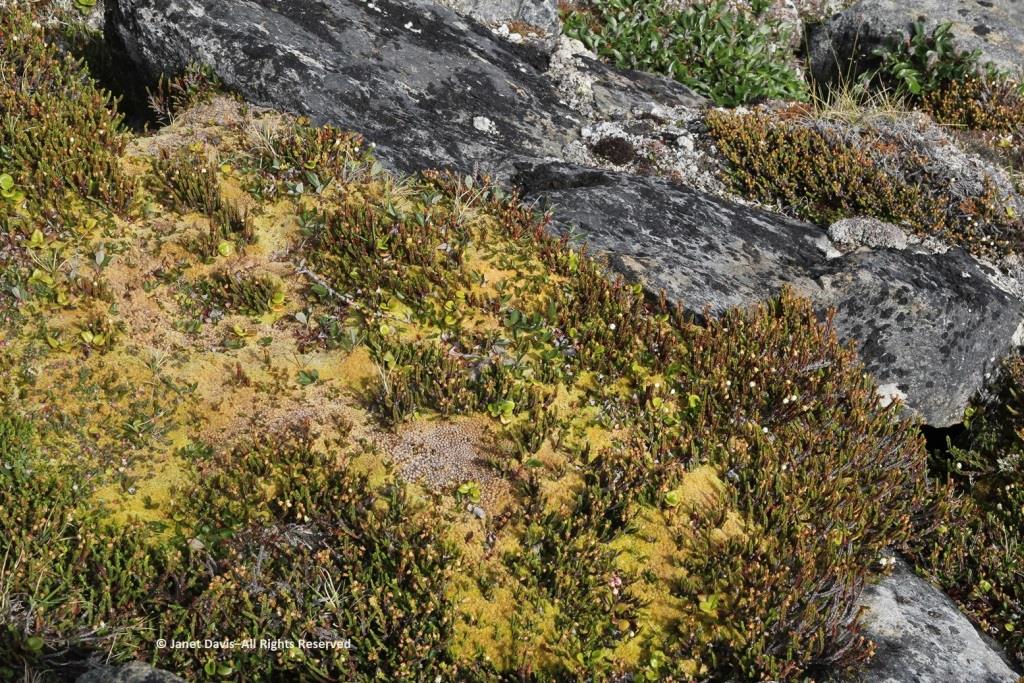

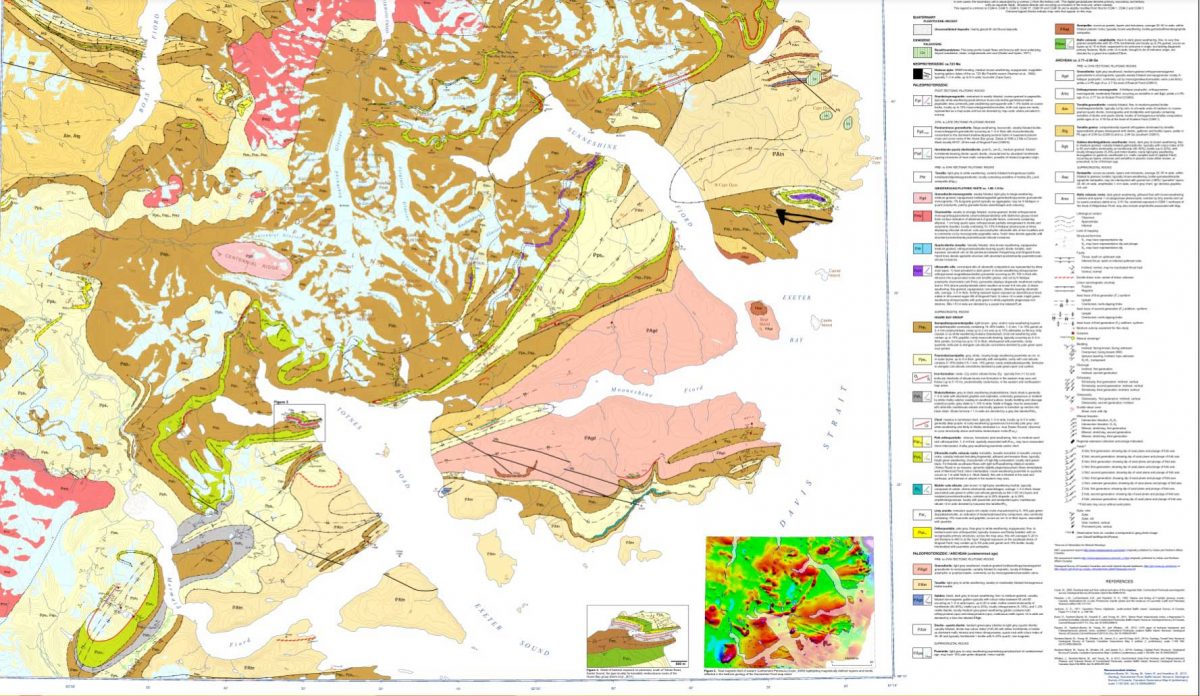

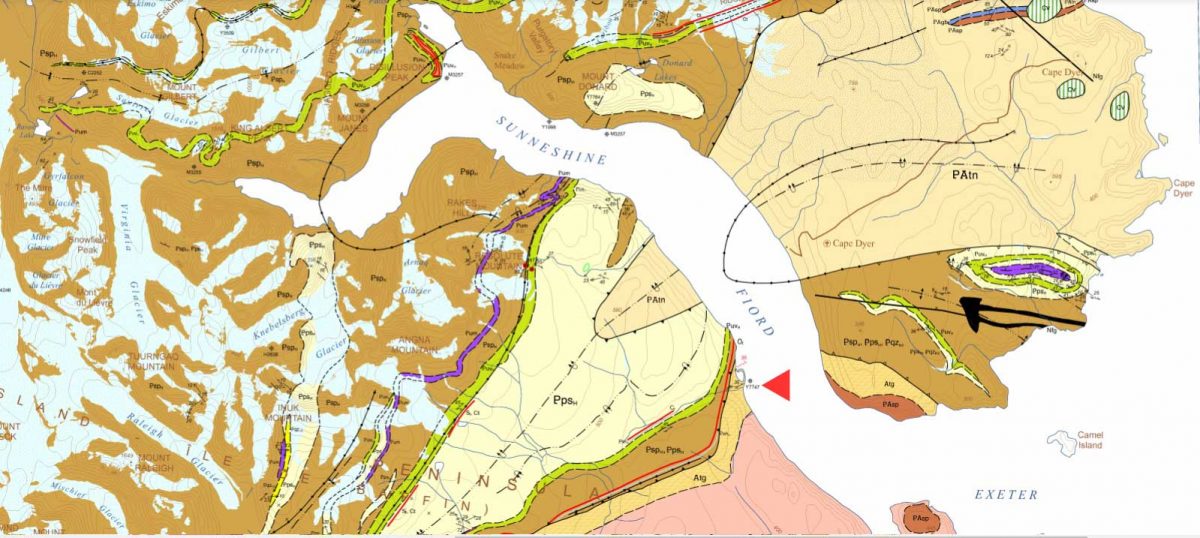

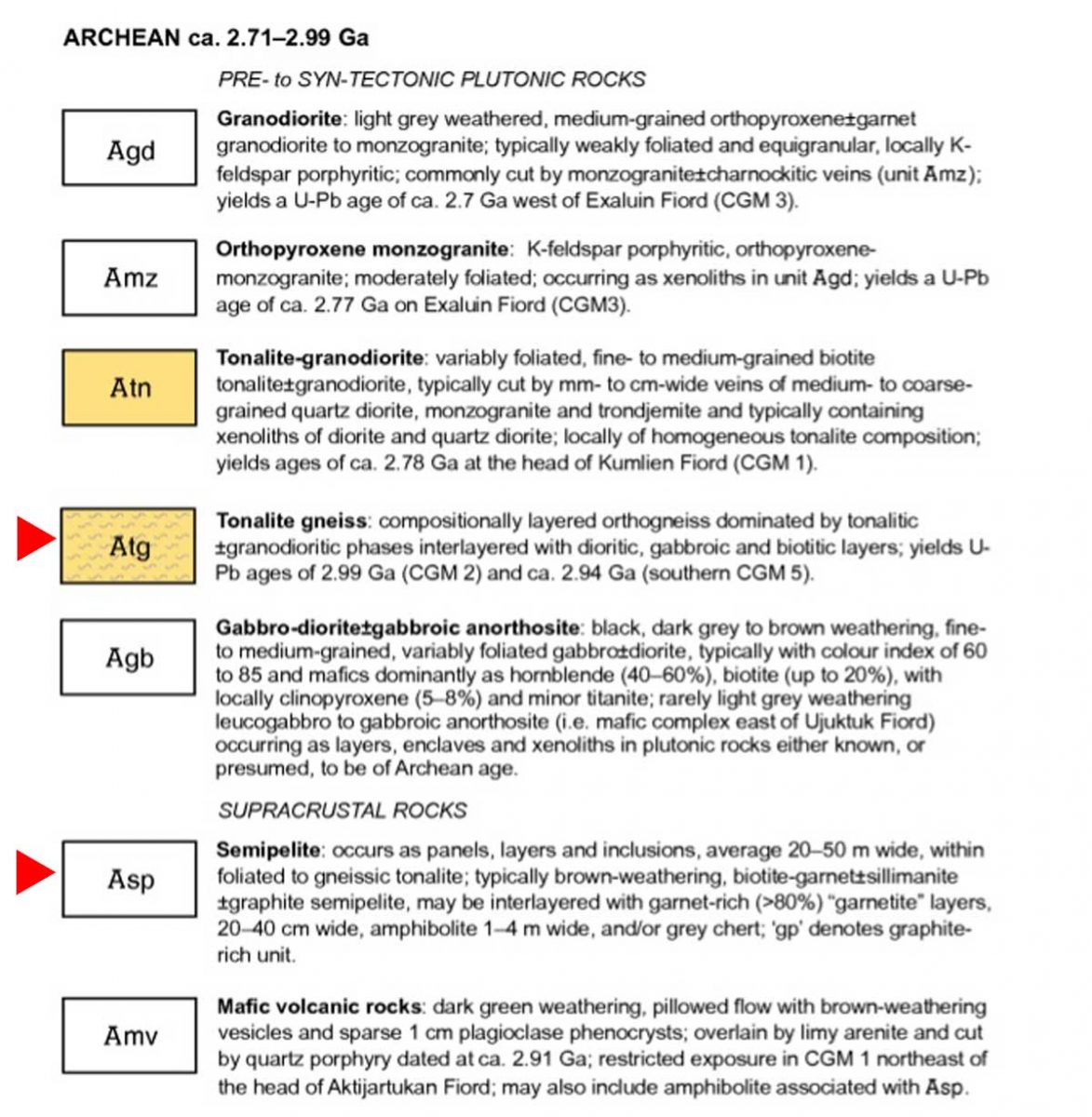

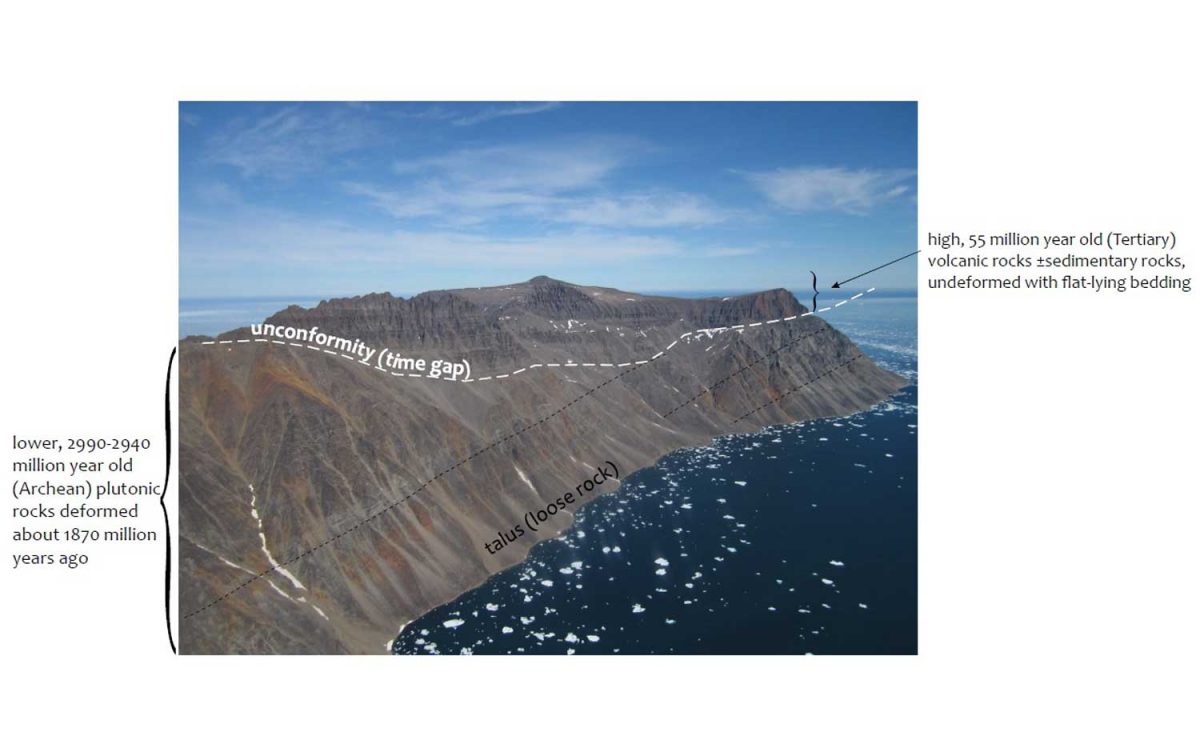

I admired these rocks at the shoreline, below. According to Canadian geologist, Dr. Marc St-Onge, Senior Emeritus Scientist at the Geological Survey of Canada, who has worked throughout the Arctic: “The bedrock geology of the Ilulissat region comprises dominantly 2.84–2.76 billion years old Archean orthogneiss (gneiss derived from a plutonic precursor), reworked and metamorphosed 1.88 billion years ago by the Nagssugtoqidian orogenic belt.” In fact, Greenland has some of the oldest known Archean rocks on the planet, with a zircon crystal from the tonalitic gneiss protolith (the original rock before being metamorphosed) at Amîtsoq near Nuuk U/Pb-dated to 3.872 Ga (Giga annum or billion years ago). Incidentally, the Greenland rock is younger than the oldest-known exposed rock in the world, the Acasta Gneiss dated at 4.02 Ga and found in 1983 by Dr. St-Onge and his geologist wife Dr. Janet King 300 km north of Yellowknife, in Canada’s Northwest Territories.

Once docked, we set off on foot to the outskirts of Ilulissat, passing the inevitable sled dogs on the way.

Before long, we arrived at the boardwalk leading to the edge of the icefjord. The boardwalk passes through the Sermermiut Valley, which was once an Inuit settlement. At 1.4 k (.87 mile) in length, it is a pleasant, easy hike, but one with a spectacular terminus that showcases one of the planet’s most awe-inspiring phenomena.

I marked the Google Earth map below with yellow arrows to show the boardwalk and its relationship to town.

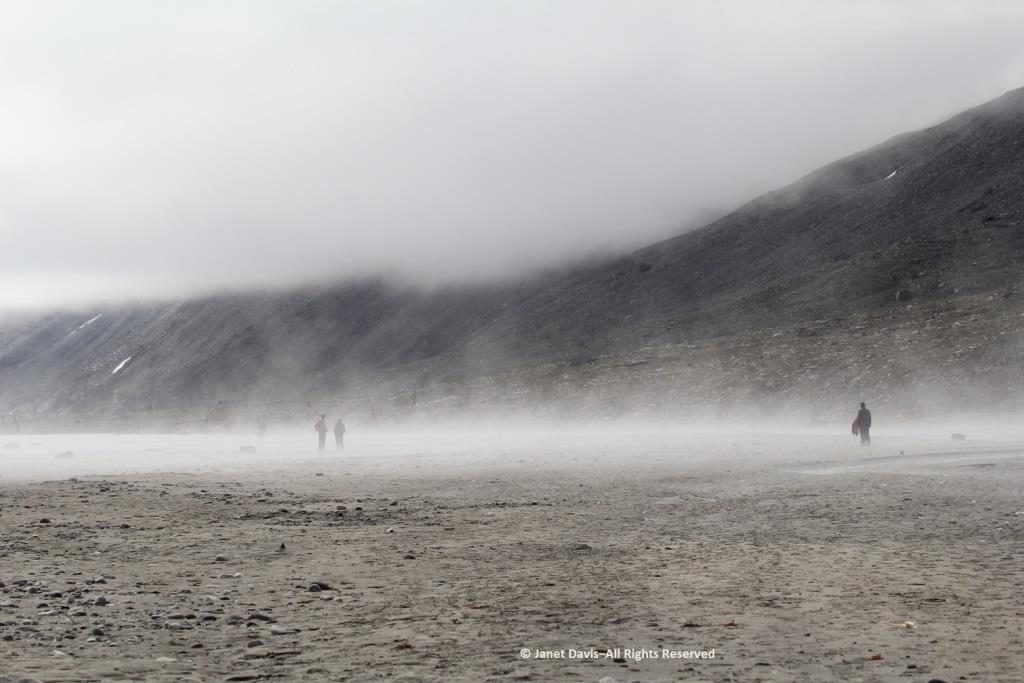

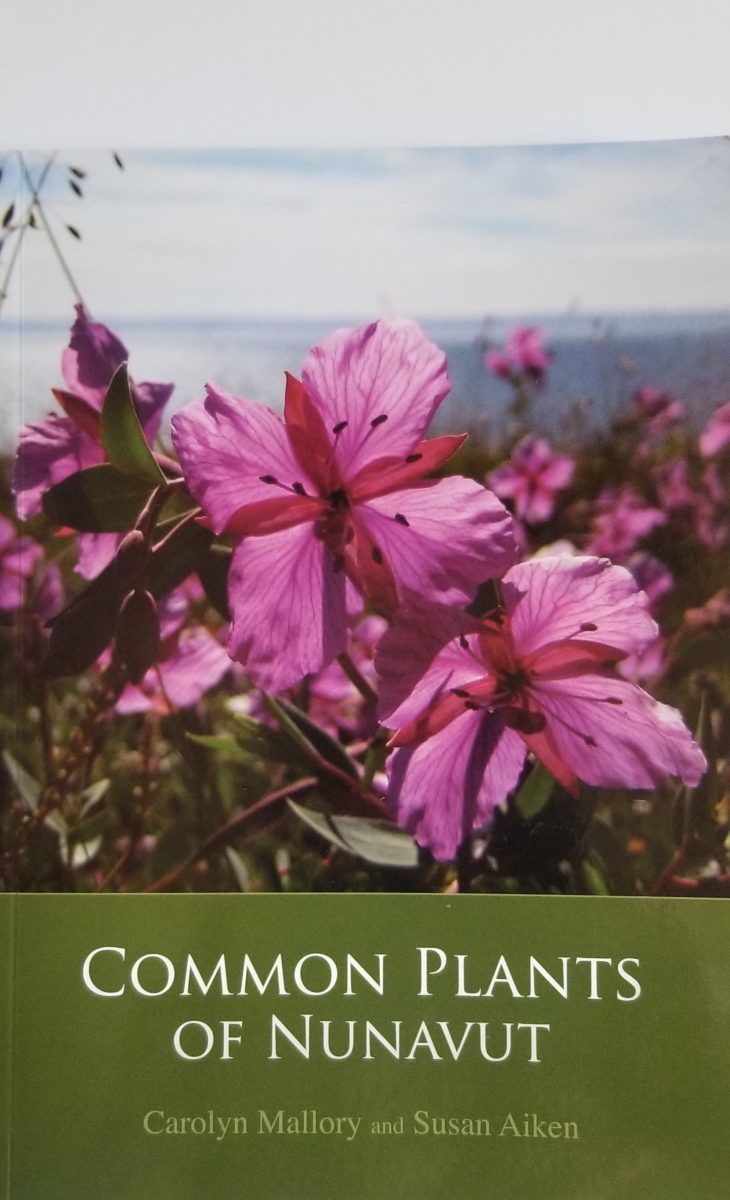

It is simply impossible to describe how thrilling it was to walk through this gentle meadow with its delicate little ecosystems of plants and ancient rock toward this massive parade of glacial ice slipping, sliding and booming towards the ocean.

In 2004, as it was creating the International Heritage Site designation, UNESCO described the site and determined that it met two criteria:

“The combination of a huge ice sheet and a fast-moving glacial ice-stream calving into a fjord covered by icebergs is a phenomenon only seen in Greenland and Antarctica. Ilulissat offers both scientists and visitors easy access for close view of the calving glacier front as it cascades down the ice sheet and into the ice-choked fjord. The wild and highly scenic combination of rock, ice and sea, along with the dramatic sounds produced by the moving ice combine to present a memorable natural spectacle.

The Ilulissat Icefjord is an outstanding example of a stage in the Earth’s history: the last ice age of the Quaternary Period. The ice-stream is one of the fastest (40 m per day) and most active in the world. Its annual calving of over 46 km3 of ice accounts for 10% of the production of all Greenland calf ice, more than any other glacier outside Antarctica. The glacier has been the object of scientific attention for 250 years and, along with its relative ease of accessibility, has significantly added to the understanding of ice-cap glaciology, climate change and related geomorphic processes.”

As usual, I was distracted with all the photography opportunities in the meadows flanking the boardwalk, and had to hurry along to catch up. (Thankfully, my friend Anne snapped this photo of me, something that rarely happens when I travel.) It was so warm that lovely day in the Arctic, I didn’t need the jacket I’d brought along. However, according to the World Metereological Organization, Greenland also boasts the lowest temperature ever recorded in the Northern Hemisphere, -69.6 C (-93.3 F) on December 22, 1991 at Klinck, with an elevation of 3,105 metres near the topographic summit of the Greenland Ice Sheet.

The calved ice loomed ahead, but I also loved seeing all the plants, like ubiquitous Scheuchzer’s cotton grass (Eriophorum scheuchzeri)…..

….. with its fluffy white fruiting heads.

The meadow was a tapestry of heath plants, blueberries, mouse-ear chickweed, willow and….

…. dwarf birch (Betula glandulosa).

In the damper spots, mushrooms emerged from luxuriant carpets of moss.

Greenland bellflower grew in drier places, (Campanula rotundifolia subsp. gieseckiana).

Alpine catchfly (Viscaria alpina) showed off its magenta flowers.

A little Lapland longspur (Calcarius laponicus) eyed me as it ate a seed.

Nearby, creeping crowberry (Empetrum nigrum) was exhibiting serious browning, a result of warm weather.

Tufted saxifrage (Saxifraga caespitosa) is one of ten saxifrage species that grow in the meadows, according to the UNESCO list of flora.

Everyone had their cameras out.

The boardwalk took us down near the meadow’s edge, where the sheer majesty of the icefjiord was on display.

You could view it from there….

….. or from the top of the rocky cliff overlooking the fjord. This was one of my favourite photos from the entire trip, simply showing the scale of the massive icebergs clogging the fjord.

Sometimes the word “spectacular” is just not descriptive enough.

There were stairs to a higher location for those who wanted a different vantage point. In fact, there are a few marked trails for those who want to venture further on the site.

From up there, I looked down on Adventure Canada’s intrepid photographer, Dennis Minty, whose photos from the various expeditions are simply beautiful.

If we ventured too far down on the rocks, someone would yell: “Move up further. If one of those icebergs cracks and breaks away, the tsunami would wash you away.”

Visitors are also warned not to stand on the rocky beach along the fjord.

To get an idea of how daunting the tsunami waves can be, have a look at this video showing a massive iceberg cracking, then turning over:

According to Wikipedia, “Some 35 billion tonnes of icebergs calve off and pass out of the fjord each year. Icebergs breaking from the glacier are often so large (up to a kilometer in height) that they are too tall to float down the fjord and lie stuck on the bottom of its shallower areas, sometimes for years, until they are broken up by the force of the glacier and icebergs further up the fjord.”

What we were looking at from our vantage point was the mouth of the glacier with its iceberg-clogged fjord. We couldn’t actually see the ice sheet itself, but it must be something to fly above its massive expanse and gaze down in summer at the meltwater lakes and rivers, as shown in the NASA photo below. Research on the ice sheet takes many forms, from Landsat and Grace Satellites with radar probing imagery to determine ice loss to long-range high-tech-equipped flights over its surface. A project called GreenDrill planned for an area near the Hiawatha Glacier in north Greenland aims to drill down into bedrock to determine the last time the ice disappeared. Last year, researchers discovered that, rather than retreating as it had done for the past few decades, Jakobshavn Icefjord had actually slowed, re-advanced and thickened for three consecutive years, mainly due to colder ocean temperatures at the outlet in Disko Bay.

The photo below shows Swiss Camp, run by the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder and set up to study the Jakobshavn glacier. Tragically, its long-time director Konrad Steffen fell into a crevasse on the ice sheet and drowned on August 8, 2020.

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

Operation Ice Bridge has collected data from Jakobshavn Glacier itself for many years. In the video below, you can see the actual calving front.

I love this photo because it contrasts two different planetary timescales: Archaean rock that is more than 1.8 billion years old and icebergs containing frozen water that might be tens of thousands years old.

To view a truly stunning gallery of images from Ilulissat, have a look at this site featuring the work of photographer Kristjan Fridriksson.

Returning from the icefjord to town was a little anticlimactic, to say the least, but it was lovely to come down to earth at the museum that was the home of famous Greenland explorer Knud Rasmussen (1879-1933).

The son of a Danish missionary and his Danish-Inuit wife, Rasmussen became an explorer and anthropologist, making seven expeditions between 1912-33 throughout Greenland and Arctic Canada as far west as Nome, Alaska.

Rasmussen was the first European to cross the Northwest Passage via dog sled.

The front door of the Rasmussen museum opens onto a spectacular view of Disko Bay – a view that likely remains mostly unchanged from his days in the house.

We inspected a typical Greenland sod house at the front of the Rasmussen museum.

Then we walked to the top of Ilulissat for a good view of the bay and a quick stroll through the residential neighbourhoods.

This house might have won the Greenland colour prize, but all the houses seemed to celebrate brilliant colour – not surprising in a place where winter lasts most of the year.

The ubiquitous false mayweed (Tripleurospermum maritimum) was in full bloom. Such a lovely native, adapted to growing in the salty air and soil of the far north seaside.

After lunch on the ship, it was time to head out on a Disko Bay zodiac excursion. The captain in this zodiac was marine biologist Deanna Leonard-Spitzer, who did the whale-spotting on our expedition.

We got as close as we could to the big calved icebergs. Given that only 10% of an iceberg is above the water surface, you get an idea here of the size of these monsters.

Photographing icebergs is a little addictive.

Although I had been warm enough to take off my coat walking down the icefjord boardwalk, being out on the water was definitely cooler.

Seagulls enjoyed perching on the icebergs as they fished. I think these are Iceland gulls (Larus glaucoides glaucoides).

For the most part, icebergs are sparkling white with the accumulated snow from… who knows how many winters? Icebergs, after all, are just massive aggregations of winter snow that has fallen on the ice sheet – packed, condensed, frozen, surface melted, refrozen, repeat, repeat, repeat – before finally calving off from glaciers in chunks and floating away in the ocean While 96.5% of earth’s water is saline, ice sheets, glaciers and permanent snow account for 1.7% (the balance is groundwater and lakes, etc.) with the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets accounting for 68.7% of earth’s freshwater. That massive volume combined with an increase in global warming resulting in melting of the ice sheets leading to sea level rise is one of the major focuses of climate scientists today.

We cruised past an iceberg beginning to melt and noticed the soot embedded in the snow. Scientists have noticed an increase in darkened snow on the ice sheets (and even in the snow atop the Himalayas) due to soot from forest fires and pollution; that darkness becomes a positive feedback loop by reducing the albedo in the ice sheet and absorbing more solar radiation, resulting in faster melting.

At the base of the iceberg, you could see the air bubbles that form part of the iceberg’s structure. These bubbles, trapped between snow layers year after year become part of the ice. When cored as part of ice sheet research, they give scientists many clues as to the composition of the atmosphere at the time they were formed, and now.

For an excellent article on The Secrets in Greenland’s Ice Sheet, read Jon Gertner’s masterful 2015 story in the New York Times Magazine. He has also written a book called The Ice at the End of the World, available in paperback from Penguin Random House.

After our zodiac tour and dinner on the ship, we were treated to a dance party by Adventure Canada’s entertainer, Thomas Kovacs. These social events were such fun and the resource staff participated on each occasion….

…. including photographer Dennis Minty, left, and now-retired Adventure Canada founder Matthew Swan, right, whose daughter Cedar Swan is now CEO of the company.

While I loved hearing them sing, as the skies darkened I found myself drawn to the quiet of the nearby deck where I was transfixed by the icebergs, now dark mauve in the golden twilight, the seabirds wheeling, the Greenland coastal mountains hulking behind.

I felt so privileged to have seen this remarkable place, to have the opportunity to glimpse the setting for one of earth’s most critical and endangered systems, and to expand in a small way my understanding of the Arctic.

*******

This is the 6th in my Eastern Arctic blog series. Be sure to read about: