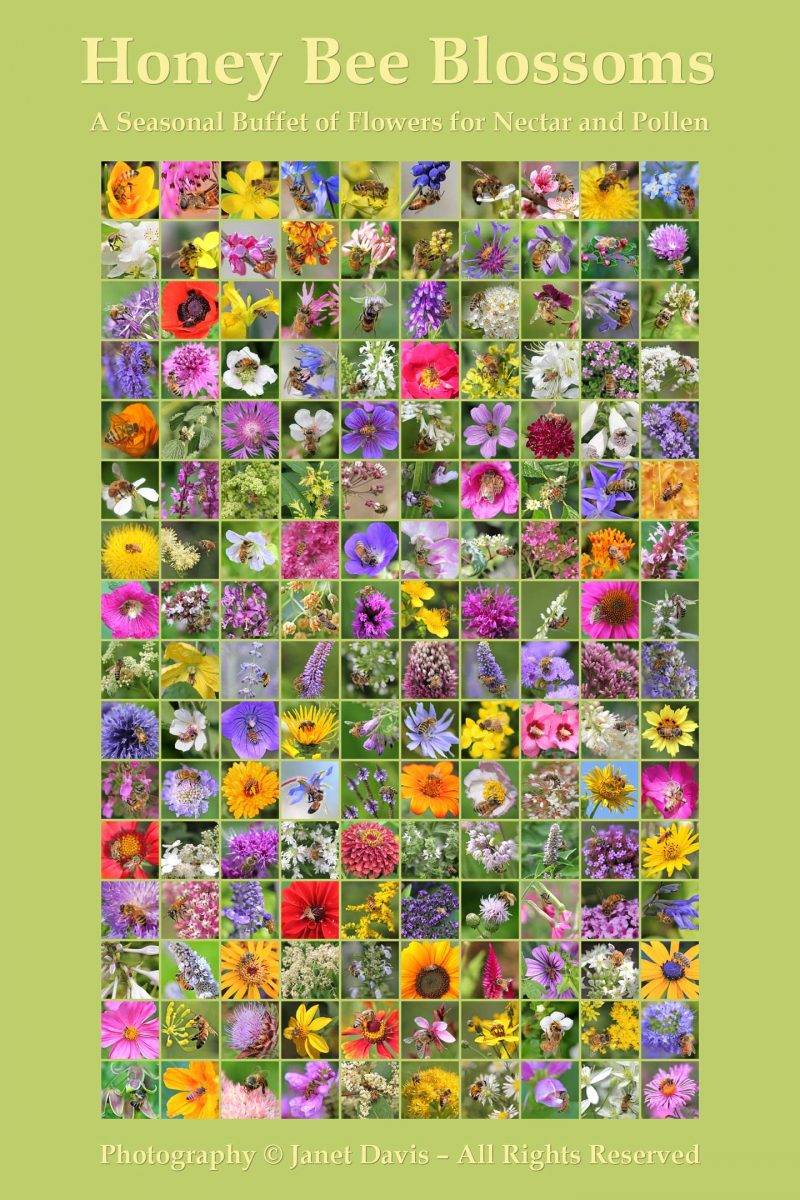

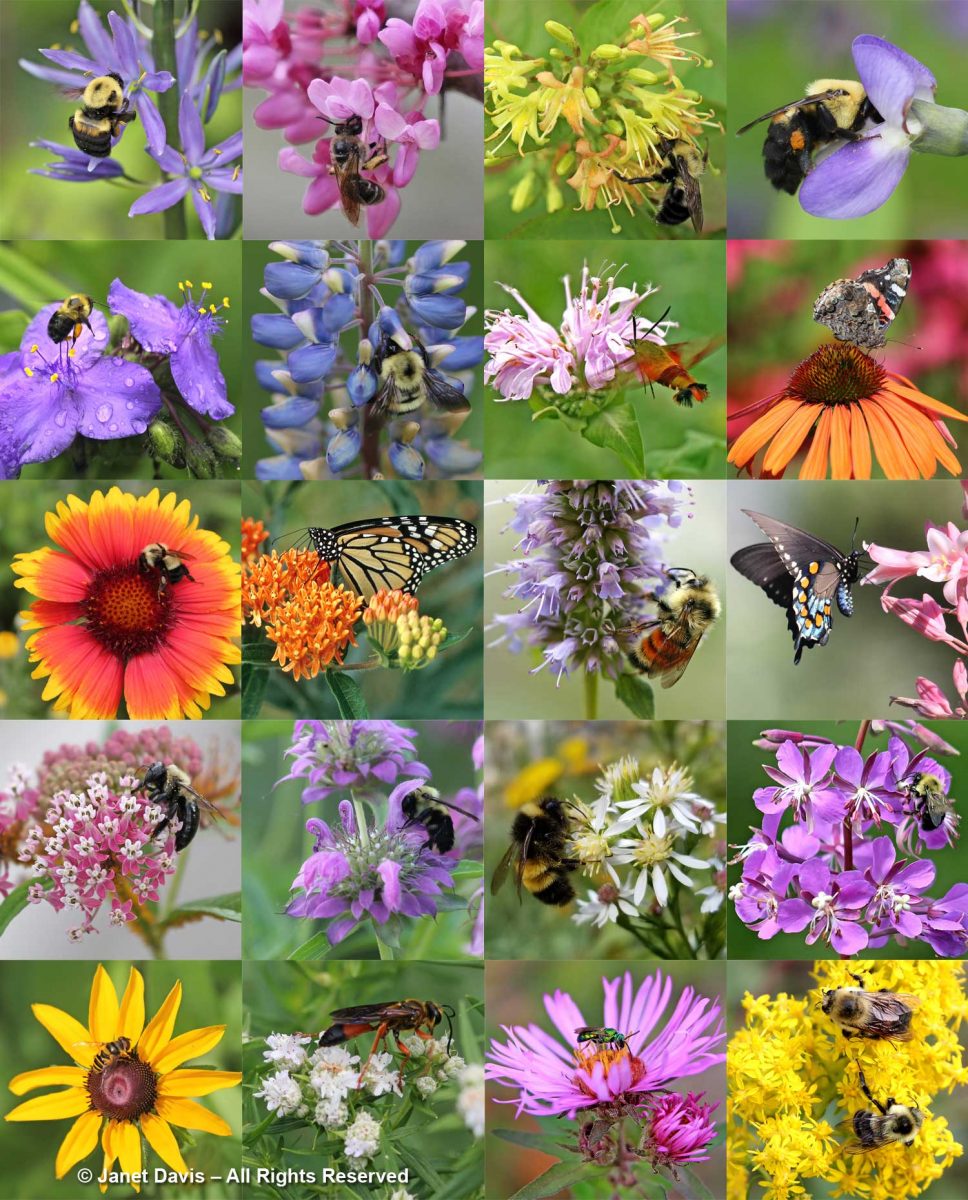

My long Covid Winter project has come to an end. Spring has sprung and I am ready to be outdoors! I began on November 1st with an entry every day, except for a few days off at Christmas. Altogether, I logged 144 #janetsdailypollinator posts over the months of November, December, January, February and now March. In going through my photo library, I have enough pollinator photos for 4 more months of daily posts, but it’s time to be in the garden. Here are my posts for March, and one GIANT family portrait at the end!

*********

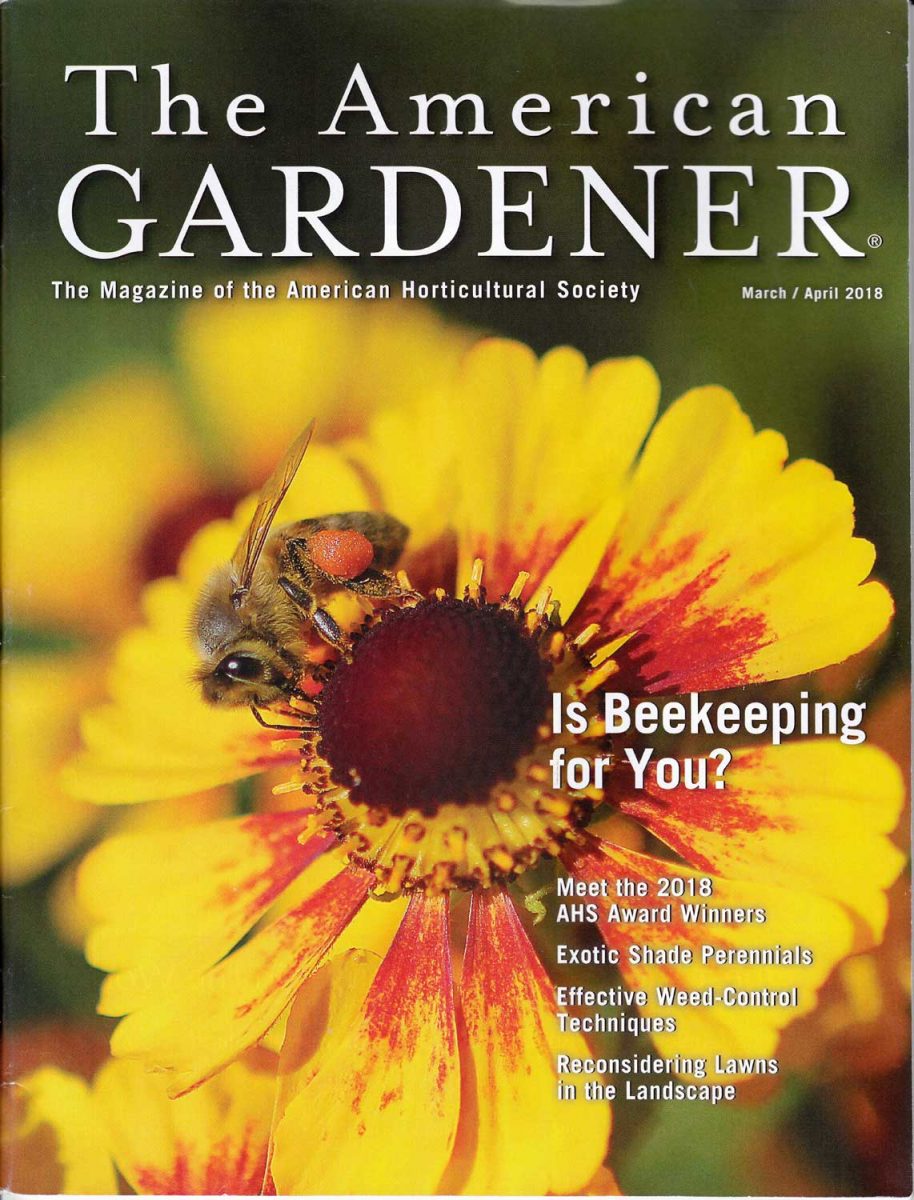

March came in like a lion… or was it a lamb? I can’t really remember, because March is March: still winter, the odd warm caress of spring, snow flurries, driving rain and the faithful return of the cardinal’s song. On March 1st, I celebrated stiff-leaved goldenrod (Solidago rigida/Oligoneuron rigidum) with honey bees, below, and recalled the way it grew in my beekeeper friend Tom Morrisey’s tallgrass prairie at his farm in Orillia, Ontario. I wrote a blog about Tom & Tina’s wonderful property and his honey harvest there.

On March 2nd I remembered all the honey bees I found feverishly gathering pollen on a southern magnolia (M. grandiflora) while I was wandering around a beach park in New Zealand. And I looked at various other magnolia species and the latest research on their ancestral pollinators.

We love preparing dishes with the leaves of culinary herbs – and bees love herb flowers! March 3rd saw me recounting the many bees I’ve seen on basil, below, as well as oregano, thyme, rosemary and sage.

Many species clematis attract bees and on March 4th I featured several, including Clematis pitcheri (below), C. koreana, C. recta ‘Purpurea’, C. jouiniana ‘Praecox’, C. virginiana and C. heracleifolia.

A favourite native wildflower – and one I grow in part shade at the cottage in Muskoka – was featured on March 5th. Golden alexanders (Zizia aurea) attracts solitary bees, especially Andrena mining bees like the one foraging below.

March 6th was my tribute to the popular European woodland or meadow sages (Salvia nemorosa) like ‘Amethyst’, below, that attract all kinds of bees during their early summer flowering.

“Seven-son flower” always reminds me of martial arts but it’s all about the Chinese translation of the seven flower clusters on the branches. Heptacodium miconioides from China was my March 7th pollinator plant because the bees adore it, especially since it flowers in late summer or early autumn when there isn’t a lot of nectar on offer.

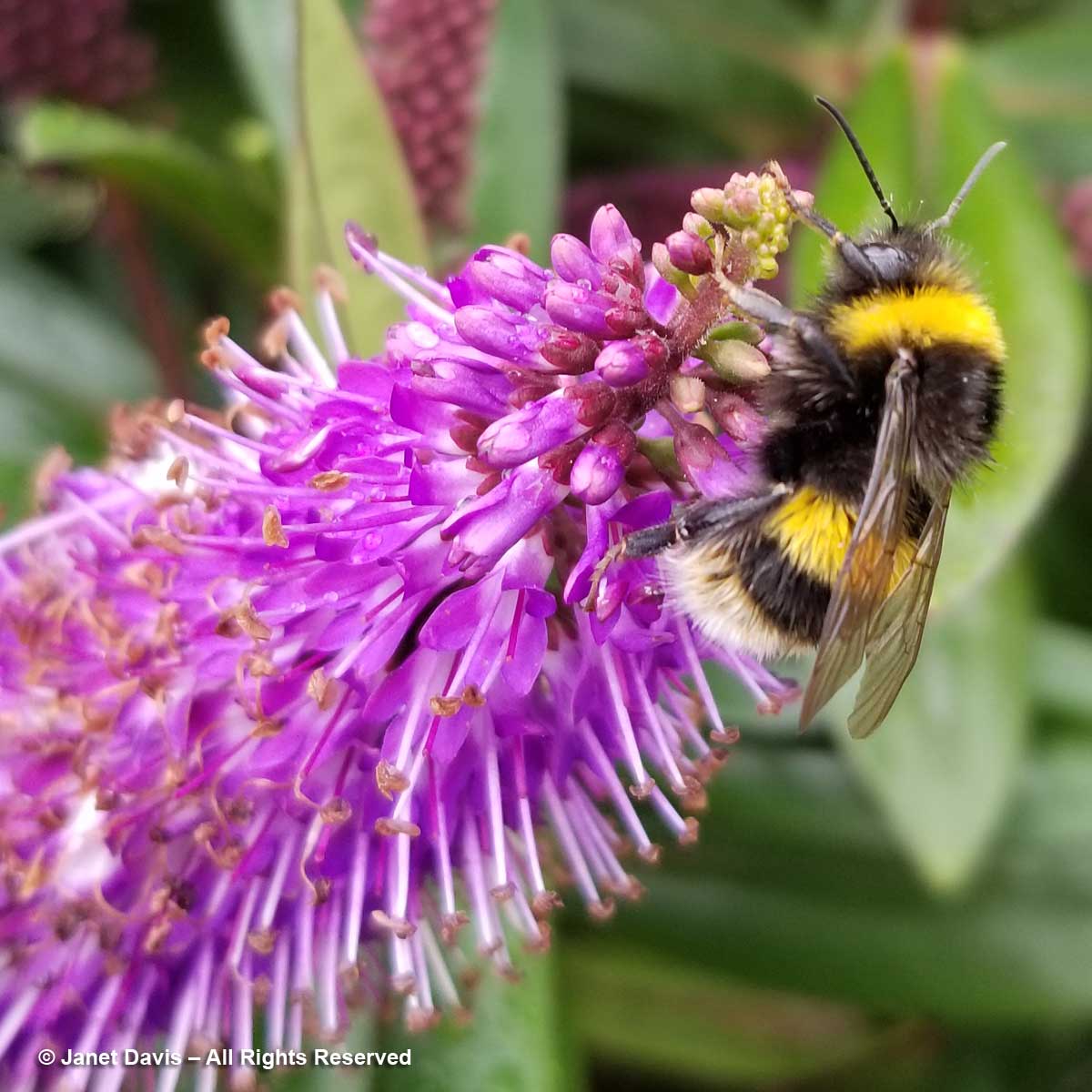

The native subshrub lead plant (Amorpha canescens) starred on March 8th and I featured photos of plants in the Piet Oudolf-designed entry border at the Toronto Botanical Garden. That’s a common eastern bumble bee (Bombus impatiens) foraging on the flowers, below.

March 9th saw me honouring ‘Jeana’ summer phlox (Phlox paniculata), a much-in-demand cultivar of an old-fashioned North American native that is absolutely irresistible to butterflies and bees. I photographed ‘Jeana’ with her insect admirers at New York Botanical Garden back on August 18, 2016. I also wrote a blog about NYBG you might enjoy reading!

I donned my rubber boots on March 10th and went into the Muskoka wetlands to check out bumble bees and dragonflies on pickerel weed (Pontederia cordata).

On March 11th, I featured hardy border sedums or stonecrops (Sedum spectabile/Hylotelphium telephium) like ‘Autumn Joy’ with pink flowers and succulent leaves. They are among the best late summer perennials for attracting butterflies and all kinds of bees.

Old-fashioned veronicas or speedwells were my pollinator choice for March 12th. Bees and wasps love them, whether the common thread-waisted wasp (Ammophila procera) on Veronica spicata ‘Darwin’s Blue’ in my cottage gardens, below, or bumble bees and honey bees on several other veronicas I featured that day.

On March 13th, I recalled my Victoria, BC childhood and the pungent fragrance of calendulas or pot marigolds (Calendula officinalis) in my mother’s garden. It was an etymology lesson that day, for “Calendar” derives from the Latin ‘calendae’, i.e. first day of the month and also gave its name to calendula, i.e. the “flower of the calends”. Because the plant flowers every month of the year in the Mediterranean ,where it is native, the ancient Romans named it for the tax assessed on the first day of each month – the calend.

I went for a ‘confusing nomenclature’ lesson on March 14th with Russian sage, Perovskia atriplicifolia. You see, it’s not really Russian but native to western China, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, Turkey. And it’s no longer called Perovskia, but Salvia yangii. Revisions to familiar old names based on genetic sequencing tend to irritate gardeners (not taxonomists), but bees don’t care at all. For them, it’s just the same nectar-filled flowers with a different name.

“Beware the Ides of March”. Every high school English student remembers that warning from Shakespeare’s ‘Julius Caesar’. For my March 15th post, I chose to go with “bee ware” for the Ides of March and picked bee-friendly, native red maple (Acer rubrum) with its abundant, early spring pollen and nectar for bees like the unequal cellophane bee (Colletes inaequalis), below. This date also initiated my final 16 days of the series, each of which will focus on a pollinator relationship for spring.

March 16th celebrated winter aconite (Eranthis hyemalis), the earliest spring bulb and a great source of pollen for bees. I also explained how this plant exhibits a temperature-mediated plant movement called thermonasty, the yellow flowers closing in cold, cloudy weather and opening wide in warm sunshine.

Willows (Salix spp.) were my focus on March 17th, being that they’re such important early-flowering sources of pollen for bees provisioning their nests, like the unequal cellophane bee (Colletes inaequalis) on pussy willow below.

On March 18th Cornelian cherry (Cornus mas) from Europe was my spring star, its clusters of tiny, yellow flowers a welcome sight for bees and hover flies. I also offered a little lesson in ancient botanical nomenclature, from Theophrastus to Gerard.

The first crocuses emerged just in time for my March 19th post honouring them as abundant early pollen sources for honey bees. I also gave a little visual lesson on the #1 threat to honey bee colonies: varroa mites.

On the first day of spring, March 20th, I honoured a sweet-scented, very early-blooming shrub that’s been in my garden for decades, Farrer’s viburnum (V. farreri), named for explorer Reginald Farrer. There are always butterflies and bees searching out nectar on the pale-pink blossoms. I wrote a blog on this plant, too.

On March 21st I posted about the little blue-flowered bulbs called Siberian squill (Scilla siberica) that appear briefly in my front garden in the 2-month parade of spring bulbs. Their bright-blue pollen and nectar is collected by bees (including native spring bees Colletes and Andrena) and butterflies. Curiosity about the interaction between native spring bees and this non-native bulb prompted me to write a 2017 blog called The Siberian Squill and the Cellophane Bee.

Bee-friendly early spring Lungworts (Pulmonaria spp.) starred on March 22nd, along with an etymology on their common and Latin names, rooted way back in the day when the white spots on the leaves of the herbalist’s P. officinalis suggested lung disease. Fortunately, medicine has become a little more evidence-based today.

“I was born in Amelanchier alnifolia”. That was my opening line for my March 23rd post, and of course it referenced my birth in the city of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, or what the Cree called Kaminasaskwatominaskwak, “the place where many saskatoon berry bushes grow”. I also explored why so many serviceberries seem to bear abundant summer fruit – without ever having had pollinators visit. That’s because (unlike the one below, A. humilis, at our cottage on Lake Muskoka) some Amelanchier species are ‘apomicts’, producing fruit asexually. If you want to read more about my visit to Wanuskewin Heritage Park outside Saskatoon, ‘where many saskatoon berry bushes grow’, this is my blog from 2018.

Bees love grape hyacinths (Muscari spp.) and so do I. On March 24th I featured the fragrant blue-flowered bulbs and all the butterflies, bees and flies that forage in the bell-shaped flowers.

On March 25th I paid tribute to crabapples (Malus), especially my little weeping ‘Red Jade’ that grows beside my lily pond. It has its problems, but on those odd-numbered years when it flowers (2017, 2019, 2021!) – being an alternate-bearer like some of its biennial-bearing wild crabapple ancestors of eastern Europe – bees and butterflies enjoy foraging on its white blossoms. Later, birds and squirrels and even raccoons enjoy the tiny red fruits.

Despite having previously posted four different alliums (onion family) for pollinators in my series, on March 26th I featured several more possibilities, beginning with Allium giganteum hosting a carpenter bee, below, but also A. cristophii, A. ‘Purple Sensation’, A. obliquum, A. nigrum, A. ‘Millenium’ and, from the veggie garden, chives, A.schoenoprasum and regular onions, A. cepa.

Blackberries! My March 27th post was a bit confessional. The fact is, I fight with my native Allegheny blackberries (Rubus allegheniensis) at our cottage on Lake Muskoka, below with a native Andrena bee, and secretly loved the jam I made as a kid in British Columbia from the highly invasive Himalayan blackberries (R. armeniacum).

Because I loved watching a rain-soaked bumble bee nectaring in the pendulous blossoms of redvein enkianthus (E. campanulatus) in the David Lam Asian garden at Vancouver’s UBC Botanical Garden, my post on March 28th paid tribute to that beautiful Asian shrub.

On March 29th, I featured a beautiful, big Asian shrub that my next-door neighbour grows – appropriately called beautybush (Kolkwitzia amabilis, recently renamed Linnaea). I always think of it as my “borrowed scenery”, to quote a Japanese design concept known as ‘shakkei’. June bees and swallowtail butterflies love the scented flowers.

Most of my garden ‘weeds’ seem to get on very well without the help of pollinators, at least none that I notice. But Virginia waterleaf (Hydrophyllum virginanum) is a little native perennial that I did not plant – i.e. a ‘weed’ in some people’s estimation – but bumble bees are so happy that it has found little niches here and there in damp, partly shaded soil. It was my pollinator plant for March 30th.

The final pollinator post of my Covid winter series for March 31st was a bulb I grow and love in my spring garden, as do the bees. Camassia leichtlinii ‘Caerulea’ is a commercial cultivar of great camas, an edible bulb native to the Pacific northwest that is nevertheless hardy in most of the northeast. In Victoria, B.C. where I grew up, the parent species is part of the Garry Oak ecosystem, along with the smaller Camassia quamash. I wrote a blog about that back in 2014. In my front garden, the tall lavender blue flower spikes look gorgeous with late tulips; in my back garden, it pairs with alliums. If it has a fault, it’s that the flowers are rather fleeting – being so beautiful, you wish they’d last much longer.

******

So that’s it. One-hundred-and-forty-four posts later, I can satisfy my love of geometry and photo montages with a BIG display of all my Covid winter pollinators. I hope you enjoyed the ones you read about, and don’t forget, if you ever want to see them again – on Facebook, Instagram or anywhere on the internet – you just have to click on the magical hashtag #janetsdailypollinator, and up they’ll come, buzzing, fluttering, rolling in pollen and probing deep into flowers for sweet nectar.