I visited the Toronto Botanical Garden this week, my third visit this year. Given the constraints placed on the garden (and I’ll get into those later), it looked pretty good. The three gardeners and volunteers have tackled most of the weeds in the main borders. The beautiful Piet Oudolf-designed Entry Border was its usual boisterous self, the spiky, white rattlesnake master consorting with the blue Russian sage….

….. and the bees were buzzing in the blazing stars (Liatris spicata).

The Entry Border sported new rails to keep out unruly, selfie-snapping visitors….

…. with a few noticeable plant additions that might not have been strictly ‘Oudolfian’, like the brilliant orange daylilies behind the rampaging Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Firedance’, below As I wrote in my 2-part, 2017 blog on the design of the border, Piet Oudolf-Meadow Maker–Part 1 and Part 2, the border was funded by the Garden Club of Toronto and constructed in 2006. Piet Oudolf recommended a full-time gardener as part of the ongoing maintenance of the entry garden. In his work with Chicago’s Lurie Garden (read my blog on the Lurie here), there was a multi-year ongoing relationship between him and the Lurie’s gardeners; that did not happen at the TBG due to financial constraints The complexity of this garden, its self-seeding plants and the ongoing assessment of performance stretches the capacity of a severely underfunded garden (I’ll get to that later, too).

However, when I rounded the corner from the entry border to the entrance courtyard itself, I was dismayed. Red and blue salvias in Victorian ribbon planting with canna lilies. It felt a little like being in a 1950s municipal park.

What happened to the creativity that should be the hallmark of a botanical garden, even in the current straitened circumstances? The little square near the entrance is prime real estate, intended to be the greeting card for all who come to the TBG. In spring, it always hosts a colourful mix of bulbs; later swishing grasses and interesting annuals and biennals. But this?

These urns used to be filled with wonderful annuals and tropicals…

…now they’re filled with dwarf hemlocks. Just plain hemlocks.

Around the corner in the garden flanking the water channel in the Westview Terrace, there were impatiens plants sprinkled throughout the perennials. Given the prevalence of devastating IDM (Impatiens Downy Mildew) over the past decade, it was a shock to see them. But it was also disappointing from a creative point of view to have your grandmother’s impatiens in what should be an inspiring border filled with high performance perennials.

And my spirits sagged further when I walked into the Edibles Garden – or what used to be the productive, instructive, nutritious Edibles Garden – to find it filled with bedding annuals in a new Trial Garden. The “Wild for Bees” installation would not be seeing a lot of activity with the annuals chosen here.

I know Ball Flora well; I’ve been to their display gardens outside Chicago as part of a bloggers’ tour. They do good work and I’m sure they’re happy to be featured here and make it an attractive partnership, financially speaking, for the TBG. But expanses of annuals are really not showing off what should be cutting edge planting design for a garden like ours.

Not to mention that the Edibles Garden as it was conceived was a source of hundreds of pounds of annual donations to the North York Food Bank. Here are some of my photos from previous years. This was 2014.

And 2016’s edibles.

A visitor from Victoria looked quizzical. When I asked what he thought, he said “They seem to be growing very common plants here.” Indeed. Instead of lantanas and petunias, what about a garden of fragrance in front of this hedge, with lilies, nicotiana, dianthus, scented peonies, heliotrope, phlox, dwarf lilac, daphne, hyacinths, clethra, etc? The TBG is light on small ‘theme gardens’ that help people design their own spaces

A bed in the Beryl Ivey Knot Garden had been planted bizarrely with Scotch thistle (Onopordum acanthium), which is as invasive a self-seeder as it is gawky. Why it would be plunked in this formal space is beyond me.

When I walked towards the perennial borders, I passed the window-box planters adjacent to the Spiral Garden. There must have been left-over red and blue salvia because these looked pedestrian, too.

In 2016, I wrote a blog on the TBG’s planter designs featuring the great creativity of the garden’s previous horticulturist Paul Zammit. The photo below shows three years of designs in these planters.

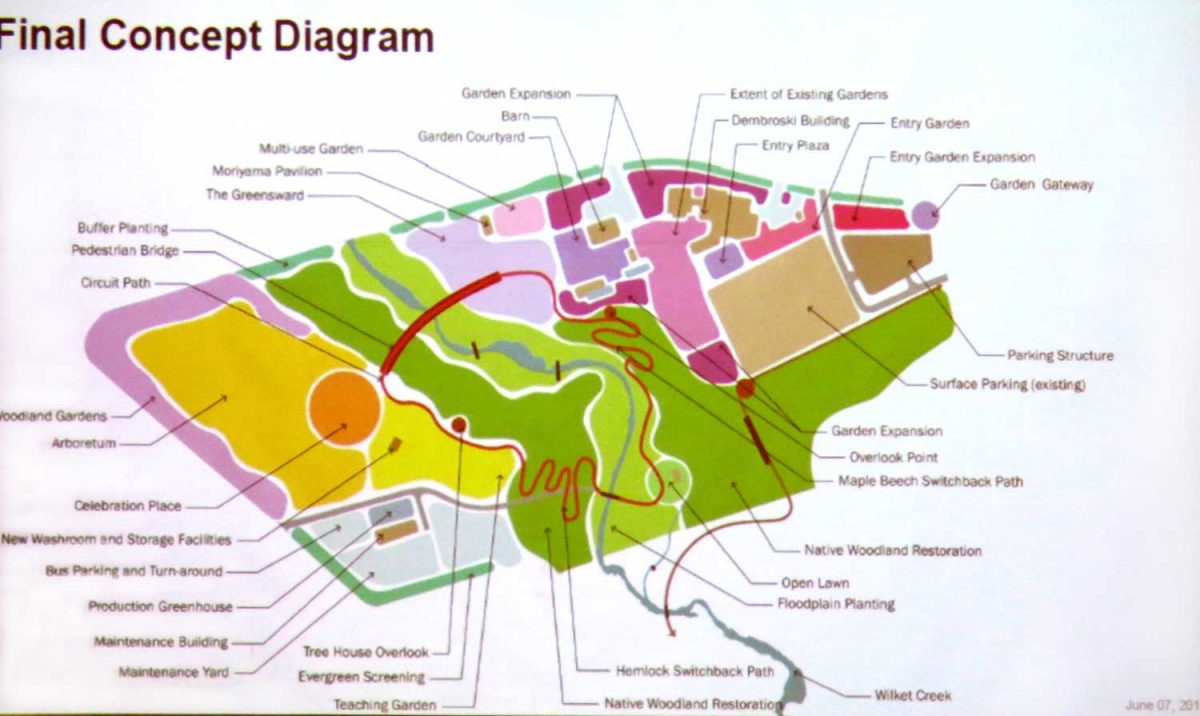

Sadly, through a lack of funding and administrative support, the TBG lost the creative minds of both the previous chief horticulturists, Paul Zammit and Paul Gellatly. My purpose here is not to retread the institutional woes, exacerbated greatly by Covid, that led to the May 22nd Globe & Mail story. It is to reflect on what made the garden brilliant as an underfunded 4-acre jewel and what looms ahead as a major 35-acre botanical garden (final concept plan below), once the merger with Edwards Gardens is complete.

On that note, I attended all three community engagement meetings with landscape architects and city planners, so I know a little of what went into the planning of the new garden, as spearheaded skilfully by former Executive Director Harry Jongerden with creative input by landscape architect W. Gary Smith, below, pointing out details on the screen.

I care very much about the garden. As well as being a long-time member of the TBG and the Civic Garden Centre before that, I have written many blogs about it: the spring tulip extravaganza; the Blossom Party; the Woman-to-Woman luncheon; the annual Through the Garden Gate Tour, and more. Since May 2007, I tallied 152 visits to photograph the garden; these provided me with the images for the seasonal photo gallery that was on the TBG’s website for several years….

……as well as for my blogs and images the garden needed from time to time. Below is garden philanthropist Kathy Dembroski at the 2018 luncheon; she and her husband George Dembroski….

….were the lead donors for the award-winning Silver LEED building opened in their name, The George and Kathy Dembroski Centre for Horticulture.

In my 33-year career as a freelance garden writer and photographer, I’ve also visited and written about a vast number of public botanic gardens, from New York, below, to Chicago, Cape Town’s Kirstenbosch, Christchurch, Kew Gardens, Los Angeles, Malaysia, Saigon and Kyoto, as well as favourite Vancouver gardens like VanDusen and UBC Botanical, among many others. I’ve also spent a lot of time in privately-funded public gardens like Chanticleer near Philadelphia and Wave Hill in the Bronx and at the iconic High Line in New York City. So I am very familiar with a broad variety of public gardens, large and small.

My husband Doug and I have been regular TBG donors for many years. As well, I have contributed various articles and donated photos to the Trellis magazine (my cover story on cottage gardening, below).

Our daughter was married at the TBG in October 2012, and we have beautiful memories of that showery autumn day.

I especially loved seeing Meredith and her attendants standing in front of the donor panels featuring my own fern photos. Our rental of the facility nine years ago tallied $5,700 for her wedding, so I know how devastating 16 months of Covid closure has been for TBG rental revenues….

….. not to mention the loss of sales from two consecutive annual plant sales and the summer fundraiser garden tour.

*******

Why am I writing this blog? It’s not to trumpet my work in gardening, but to share a concern I have. Following the TBG’s Annual General Meeting in June – an online meeting that painted everything as rosy and was carefully scripted to exclude any critical commentary from members upset with board decisions – acting Board Chair Gordon Ashworth encouraged members to send in any issues they might have. This is my response. In a word, it has to do with MONEY. At 35 acres, the expanded TBG will present both a great opportunity and an ongoing challenge to bring ground-breaking horticultural and environmental displays to Greater Toronto’s 6 million people, as well as providing inspired educational programs for children and adults. Ironically, the TBG’s current fiscal challenges have come at the same time as the federal and provincial governments announced a $2.2 million investment in Burlington’s Royal Botanical Gardens, below, as part of its 25-year master plan. Without taking anything away from the RBG and notwithstanding its 300 acres of gardens and 2400 acres of land stewardship, it is not positioned in the centre of the 4th largest metropolis in North America.

In 2012, I attended a city council meeting at City Hall to support the TBG’s then Executive Director, Aldona Satterthwaite as she begged for more financial support than the paltry $25,000 the city has traditionally given the garden in order to overcome a small deficit caused by the lack of potential revenue owing to the protracted parking lot renovation, a lot used mutually by Edwards Gardens and the TBG. I made the photo below in spring 2012; the work went on for months and months. Naturally, facilities rentals declined sharply. Through the efforts of Ward 15 City Councillor Jaye Robinson, bridge funding was secured to keep the garden solvent.

At that City Hall meeting, former Councillor Janet Davis (my doppelgänger) asked me during a scrum if I knew how much other gardens charged for admission. I answered that most had an admission fee except ours. In the case of privately-run, 55-acre Butchart Gardens in Victoria, which receives more than a million visitors annually, it is very steep, reflecting the cost of running a world-class garden (not a botanical garden, but useful for comparison). In 2013 when I photographed the entrance, below, it was $28; it’s now $36. Well-run, creative gardens cost money. It’s that simple.

I make this point because one of the major conditions in the expansion plan between the City of Toronto and the TBG is that admission to the expanded 35-acre botanical garden be free. At first glance, this is in keeping with ‘park’ policies; you don’t pay to visit High Park or any of the city’s many excellent parks, and Edwards Gardens is a large ravine park currently accessed via the renovated parking lot whose significant parking fees now thankfully accrue to the TBG. But once the TBG and the park are amalgamated, is free entry really the right financial vision for a botanical garden in the 4th largest city in North America? Or is it a lack of vision rooted in unreality? Or just thinking small? Here is a table I made with the admission costs and membership fees of botanical gardens I’ve visited.

| BOTANICAL GARDEN | Adult Entry | Annual Membership |

| Toronto Botanical Garden | Free | $45 |

| Royal Botanical Garden | $19.50 | $85 |

| Montreal Botanical Garden | $16.50/21.50* | $45 |

| VanDusen Botanical Garden | $11.70/8.40* | $45 |

| UBC Botanical Garden | $10 | $55 |

| Butchart Gardens | $36 | $69 (annual pass) |

| New York Botanical Garden | $28-23 | $98 |

| Chicago Botanic Garden | $24-26* | $99-$72* |

| Missouri Botanical Garden | $14-6* | $50 |

| Denver Botanic Garden | $15 | $55 |

| San Francisco Botanical Garden | $12/9* | $70 |

| *Variable pricing due to weekend/weekday, seasonal, or geographic parameters. |

The now defeated Rail Deck Park project proposal is a cautionary tale of planning without financing. In a May 13th editorial, the Toronto Star put the blame for the failure of the Rail Deck Park at the feet of the city and Mayor John Tory. “In 2017, the city designated the rail corridor as parkland but still didn’t move to acquire the air rights, through a negotiated purchase or expropriation if necessary. And it didn’t earmark the estimated $1.7 billion the project would cost or even explain how it intended to fund Toronto’s “next great gathering space.” It would be disastrous if our expanded TBG suffered from the same lack of realistic financial planning. Its needs will be much greater than a municipal park.

In her opening remarks during the June AGM, Councillor Jaye Robinson said that “getting the Master Plan through city council was not for the faint of heart. Very little support, quite frankly, but I got it through by compromising and we’re very excited to see this institution grow to 35 acres.” She also said that she and Ward 25 Councillor Jennifer McKelvie moved a motion to make 2022 The Year of the Garden in Toronto. That will be great — but why so little support?

We can only hope that life will return to some semblance of normal before long, and that activities will resume that require rental facilities like the TBG, thus returning it to a level of financial security. Development personnel will start knocking on doors looking for donors for the exciting expansion. And the lead landscape design firm PMA Landscape Architects will begin rolling out detailed designs for the new garden areas. The relationship between current city park personnel and TBG staff and volunteers, like those below, will hopefully be engineered to co-exist smoothly. But my fervent wish is that the amalgamation comes with a better financial framework from the city, province and federal governments that recognizes the real importance of the botanical garden to Canada’s largest city and its diverse and growing population.

On that note, I leave you with a little musical glimpse at the other population that the Toronto Botanical Garden serves.