On Victoria Day weekend, with almost two warm weeks having elapsed since my first May wildflower foray into the woods flanking the dirt road near our cottage on Lake Muskoka, near Torrance, Ontario I was curious to see what else had come into bloom. This time, knowing the blackflies and mosquitoes would be active, I came prepared with a Coghlan’s head net for my hat. What a lifesaver that was!

As I left our place on the Page’s Point peninsula, I noticed the sand cherry in flower down by the shore. Prunus pumila is a plant not only of sandy shores along the Great Lakes, but of smaller lakes, too. It also emerges from soil in granite outcrops, like Lake Muskoka.

Spring bees love the sand cherry flowers. This is an andrena mining bee.

Lowbush blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium) were in flower, too. Fingers crossed for sufficient rain to produce fruit.

I also noticed the rather subtle flowers of limber honeysuckle (Lonicera dioica), another Muskoka native.

Further down the path was a little stand of gaywings, aka fringed milkwort (Polygala paucifolia).

Back on the dirt road, hepatica, spring beauty and dogtooth violet were all finished, but I found some sweet little downy yellow violets (V. pubescens) in the grassy centre of a neighbour’s driveway.

Wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis) was now in full bloom.

False Solomon’s seal (Maianthemum racemosum) was just about to flower…..

…. .and across the road, little starflower was becoming used to its new name, Lysimachia borealis (formerly Trientalis).

I stepped down into the wetland on either side of the road to get a better look at the violet that my Field Botanists of Ontario Facebook page had identified for me in my last blog. You can see it in the mud under the emerging royal ferns (Osmunda regalis var. spectabilis). It’s called Macloskey’s violet or small white violet (Viola macloskeyi) and is native to much of northeast N. America. This is when I really appreciated my bug veil!

Here’s a close-up look at the violet.

In the wetland on the opposite side of the road, cinnamon ferns (Osmundastrum cinnamomeum) had mostly unfurled since my last visit.

There were masses of Macloskey’s violets here too, but what was that white flower at the edge of the swale?

It was wild calla or water arum (Calla palustris) – my first time seeing this lovely marginal aquatic plant.

Wild calla bears the spathe-and-spadix floral arrangement typical of the Arum family (Araceae). According to the Illinois Wildflowers site: “The spadix has mostly perfect (bisexual) flowers… These small flowers are densely arranged across the entire surface of the spadix and they are numerous. Each perfect flower has a green ovoid pistil that is surrounded at its base by 6-9 white stamens”. Flies are its principal pollinators. After flowering ends, the spathe and spadix both turn green. As fruit develops, it turns bright-red.

I actually made a little video of my foray into the wet areas and you can hear the mosquitoes in the blue violet segment, as well as the lovely Muskoka birds. It ends with the chokecherries (Prunus virginiana) further up the dirt road.

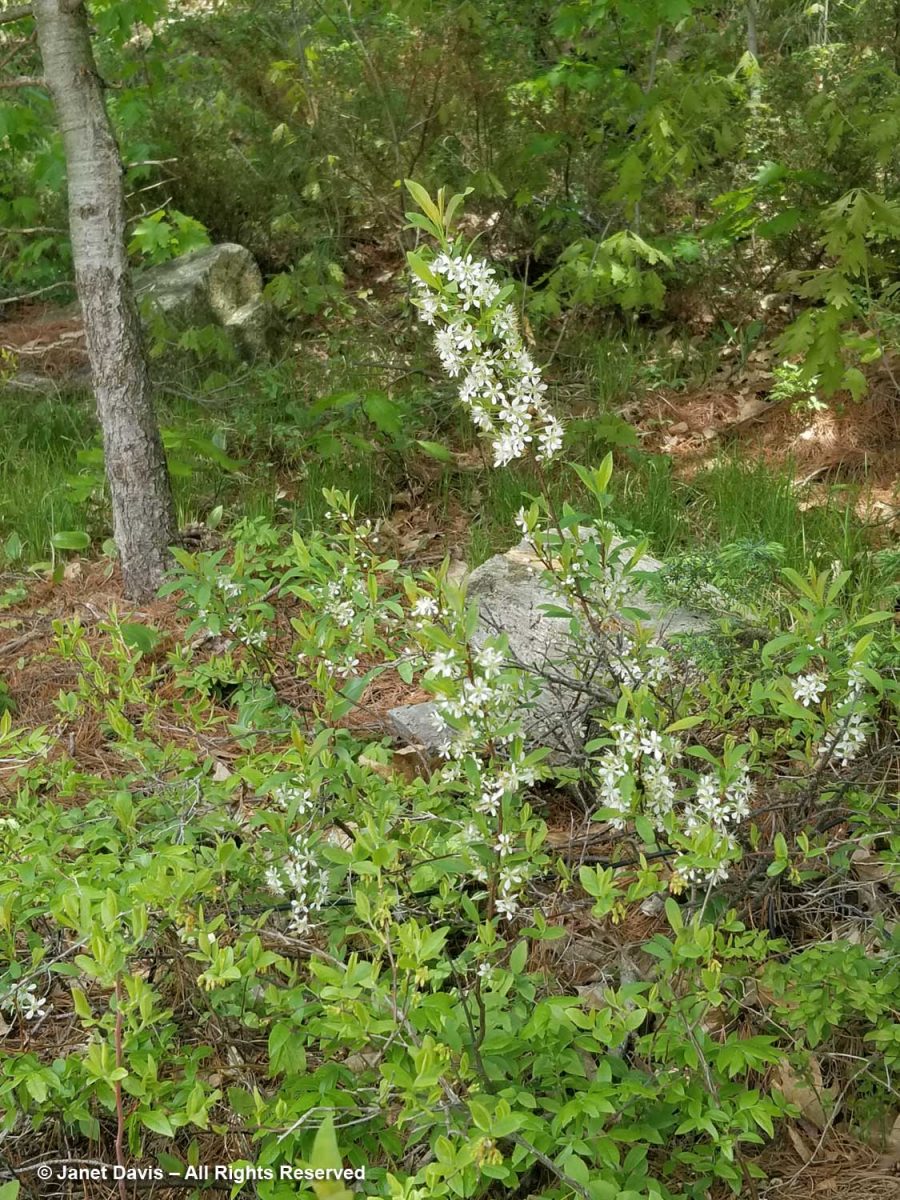

The chokecherries had just been in bud two weeks earlier, but were now in full flower….

….. and hosting native bees as well as this little beetle.

In the woods, beaked hazel (Corylus cornuta) had leafed out.

Eastern columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) grew here and there on shallow soil atop rock outcrops.

I saw exactly one rock harlequin (Capnoides sempervirens) but it was difficult to capture with my cellphone so I’ve added a camera closeup from a previous spring behind our own cottage.

And of course loads of wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana).

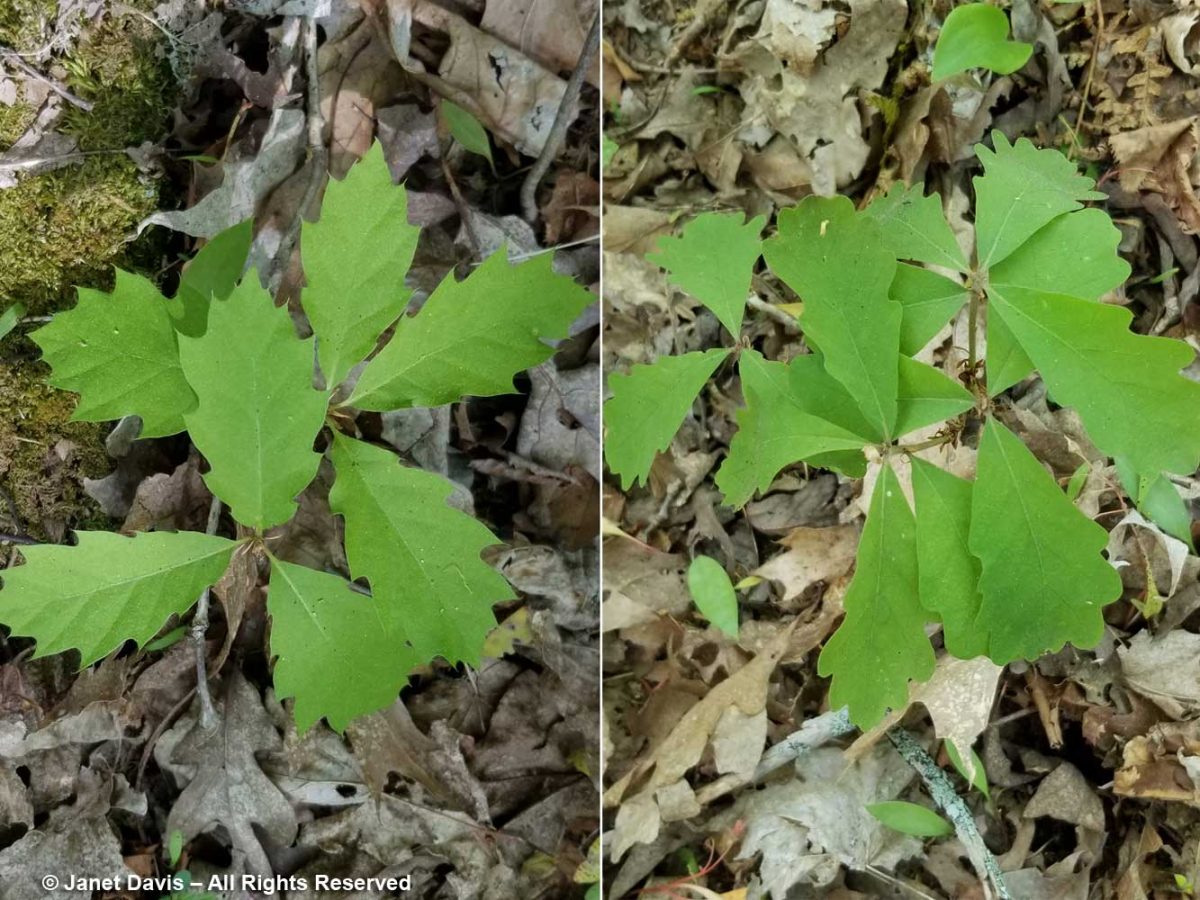

The forest floor under this sugar maple seedling (Acer saccharum) was thickly carpeted with the leaves of countless species still awaiting their time to shine – or perhaps never rising at all, but merely part of the great fabric of nature here.

There were also seedling oaks, both red oak (Quercus rubra) and white oak (Quercus alba). The latter, in this neck of the woods, never seems to get bigger than a small scrubby tree.

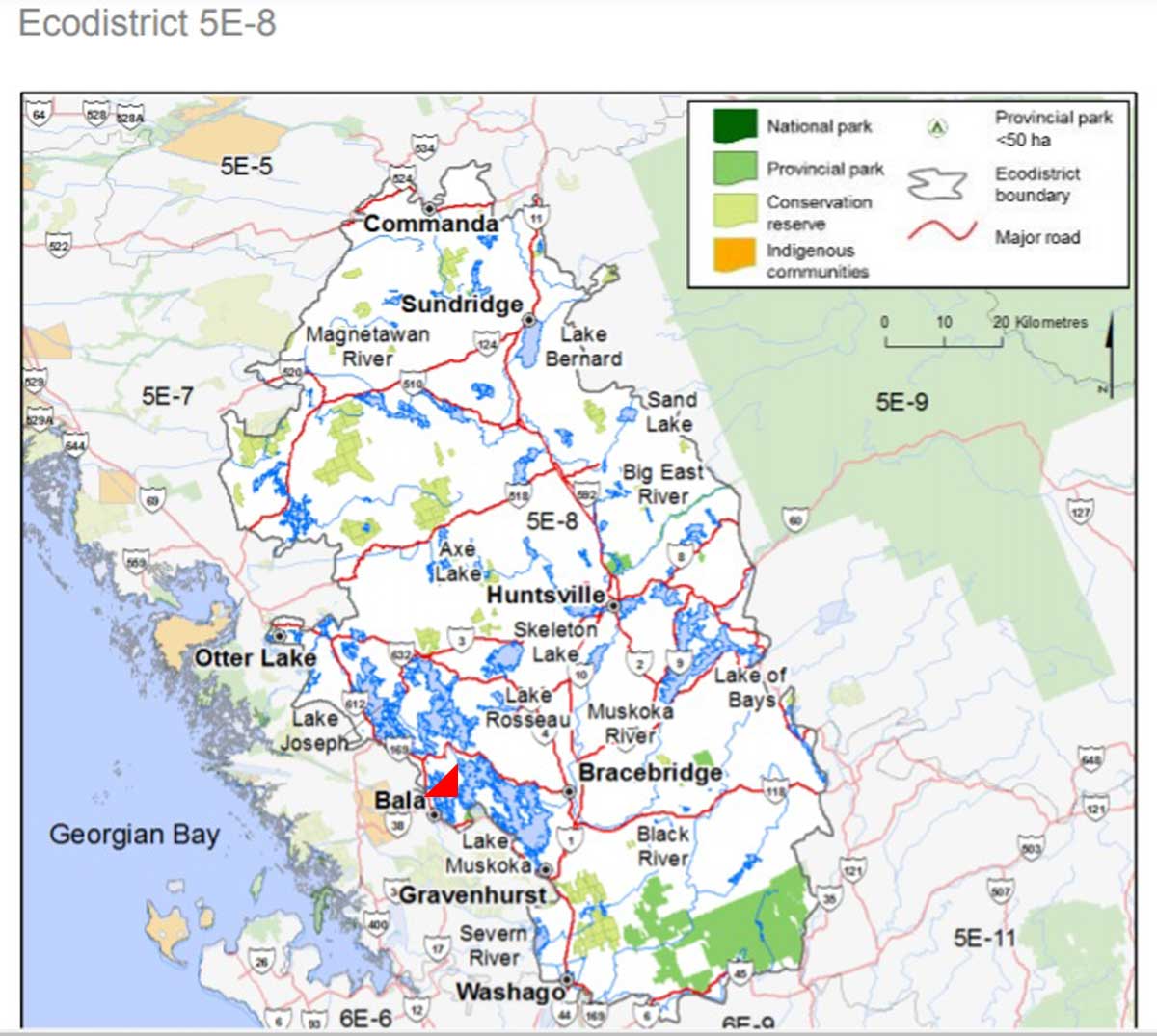

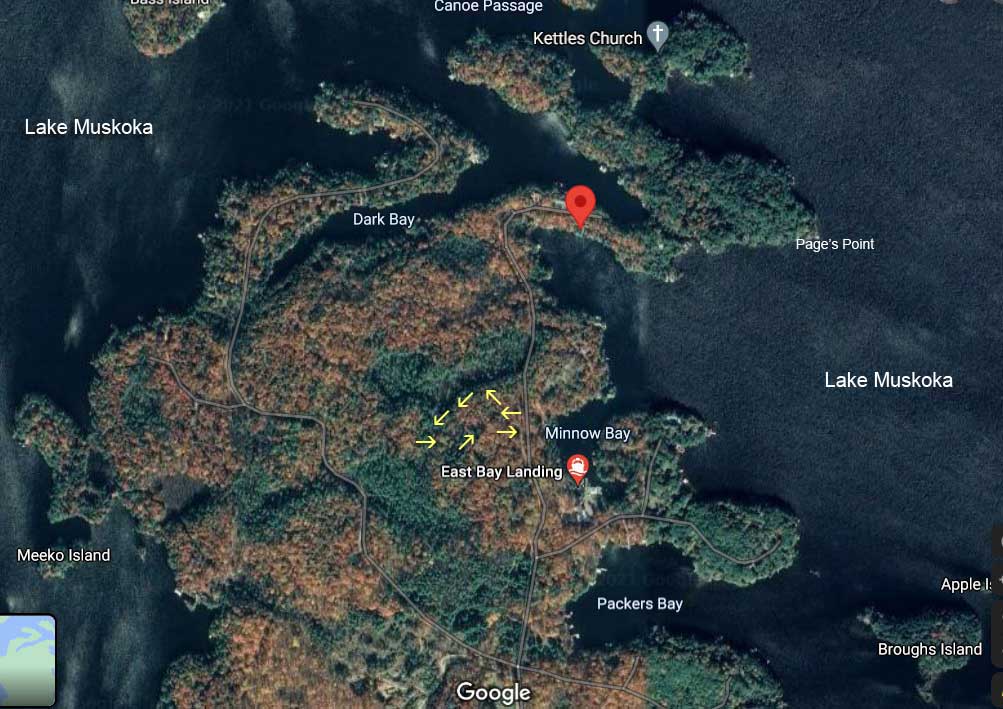

Those oak photos were the last ones I made for 30 minutes because I got turned around and lost in the woods. It was only for a half-hour, but it felt like hours. I climbed over and under downed trees and came to hemlock stands and fairly high cliffs, beyond which lay… more forest. Since it was mid-afternoon, I followed the sun, thinking I needed to go south – but I was in fact walking more west than south. Nothing looked familiar – I was really lost, and getting thirsty in the heat! Feeling a growing sense of panic, I called my husband Doug back at the cottage. “You need to veer left as you’re looking at the sun to find the dirt road,” he said. Within 10 minutes I started to recognize some of the plants I’d seen earlier and then I heard the voices of children and saw the roof of a truck heading down the dirt road. Whew! Next time I won’t wander without taking water and leaving a trail of cookie crumbs! (Note to self: also get compass and GPS apps on phone.) The arrows below with our cottage marked in red approximate my wanderings.

When I got back to the dirt road, I found the first instar of the gypsy moth caterpillars that will ravage our Muskoka oak and pine trees this summer. Very tiny, it was crawling up the leaf of striped maple or moose maple (Acer pensylvancum) which was also sporting its pendant green flowers. Some of my readers will recall my 2020 blog A Gypsy Moth Summer on Lake Muskoka in which I described how I used a homemade oil spray to kill the egg masses.

Heading back to the cottage, I found maple-leaf viburnum (V. acerifolium) in bud…..

….. and a few trilliums that had not yet withered in the unseasonal May heat. And I had learned a few valuable lessons about going into the Muskoka bush alone!

**************

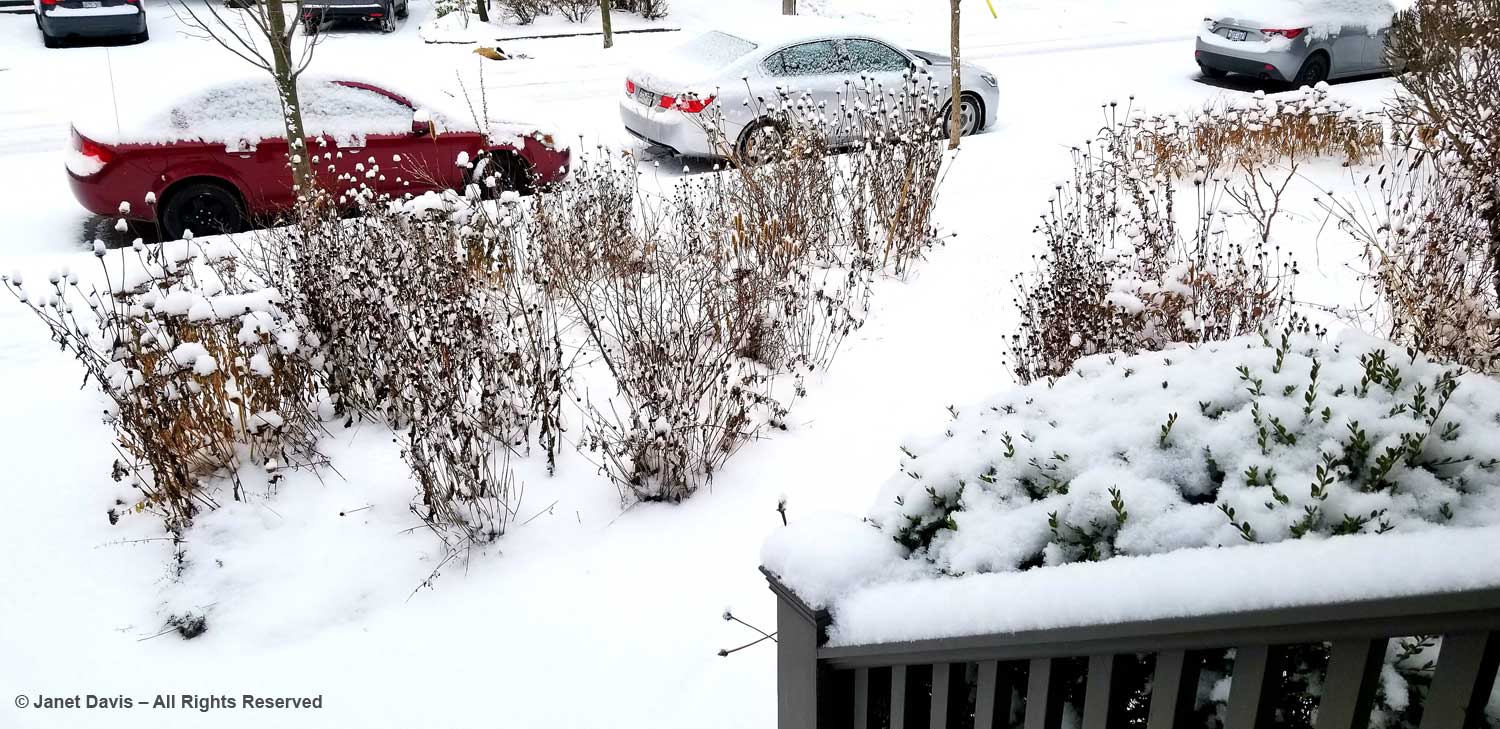

If you want to read about my meadow gardens in Muskoka, have a look at this blog from 2017, Muskoka Wild – Gardening in Cottage Country.