It’s summertime in the city! The days are warm and the garden is abuzz with insects. My 15th fairy crown for July 18th features the romantic hues of purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), Clematis viticella ‘Polish Spirit’, drumstick alliums (Allium sphaerocephalon), anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) and pink Veronica longifolia.

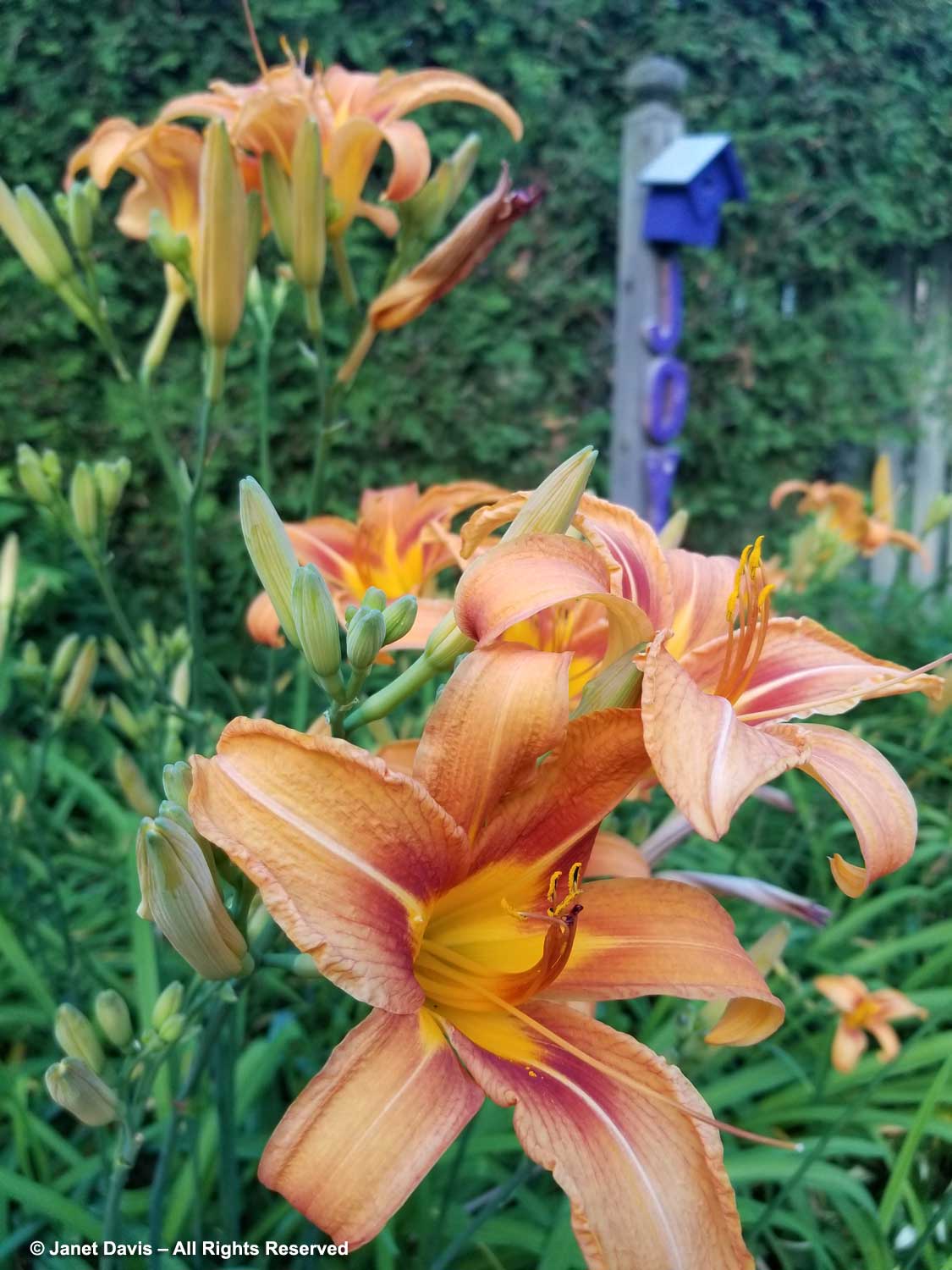

If you say you’re designing a garden for pollinators in the northeast and you haven’t included purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea)….

….. your bees and butterflies are missing out on a lot of good pollen and nectar. Native to the mid-central United States, it is easily grown in well-drained, adequately moist soil in full sun.

The insects are attracted to the tiny, yellow disc flowers in the central cone, which open sequentially from outside in over a long period in July-August.

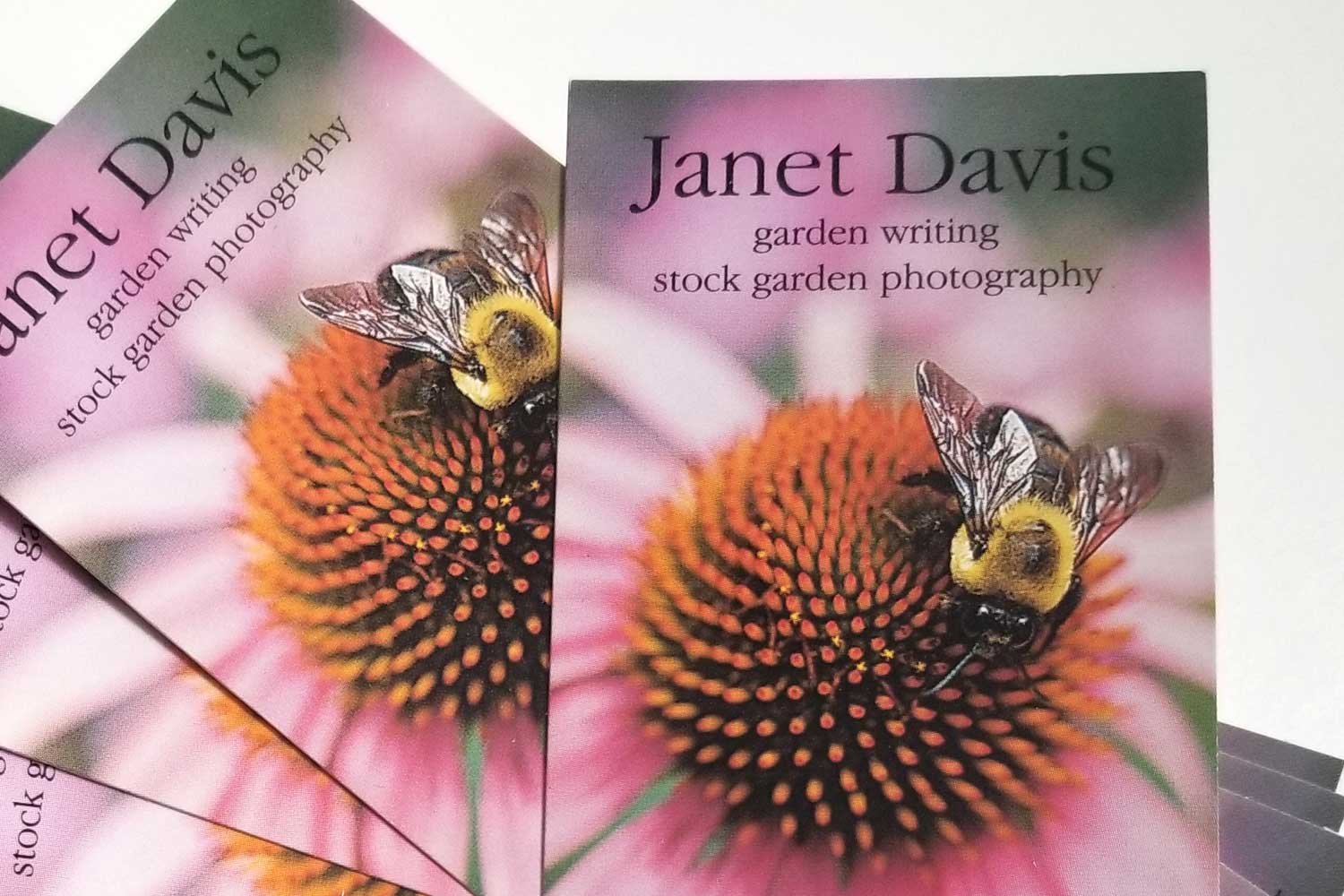

In my long career photographing flora, purple coneflower has always been dependable for capturing bumble bees, because they tend to move slowly across the cone. Bumble bees, honey bees and butterflies with long tongues are especially drawn to purple coneflower. Sometimes I’ll find two or three bumble bees sharing the cone, occasionally with a butterfly

In fact, my business card from the 1990s features Bombus impatiens, the common eastern bumble bee, patiently working the tiny flowers. But not all coneflowers are alike: those with doubled petals or hybrids with the less hardy, yellow-flowered E. paradoxa that produce the apricot, orange and red flowers are not nearly as attractive to pollinators. Stick with the straight species, or with older cultivars like ‘Magnus’ and ‘Rubinstern’ (Ruby Star), both 3-4 feet (90-120 cm) tall.

If purple coneflower likes your garden, it will spread easily… perhaps a little too easily, but seedlings are easy to remove.

You should know, however, that once the bees have finished pollinating the flowers, the nutritious seeds are food for hungry goldfinches in autumn. I have even filmed a downy woodpecker hammering on an echinacea to get at the seeds. That’s why I never cut down my purple coneflowers until late winter and little seedlings everywhere are the result. In my front garden, that hasn’t been a problem, since other perennials and shrubs are well-established, but thinning out the population periodically is necessary.

Here’s a little video I made a few years ago, illustrating why it’s important not to deadhead your purple coneflowers.

I love anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) for its long-lasting, pale-lavender flower spikes….

…..and its superb appeal to butterflies and bees, especially bumble bees. Ultra-hardy and native to much of the north-central U.S. and southern Canada, it is a short-lived perennial but will usually self-seed.

Tucked into my crown are a few dark-mauve drumstick alliums (Allium sphaerocephalon). Native to the UK, southern Europe and north Africa, their egg-shaped inflorescences add a punctuation note to my July pollinator garden, where they attract butterflies and bees.

Over the decades, I’ve watched many clematis vines come and go in my garden, especially the large-flowered hybrids which can develop clematis wilt, leading to their demise. The plants I grow need to be fairly self-reliant and that isn’t always the case with clematis, which also have varied pruning needs according to their flowering type. But among the survivors is a favorite, Clematis viticella ‘Polish Spirit’. Bred in Warsaw in 1984 by the Jesuit priest Stefan Franczak, its name honors the resilient spirit of the Polish people following World War II.

Masses of velvety, purple flowers appear on twining 8-foot (2.4 m) vines in July and August. My plant is trained on a metal obelisk and flowers appear all the way to the top, where they spill through a reproduction sphere armillary or astrolabe. Like all clematis that flower on new growth (Group C), Clematis viticella and its cultivars should be pruned back hard to just above the third set of plump buds in early spring.

With such a profusion, I never mind cutting a few clematis stems for small nosegays.

Although it doesn’t play a big role in my garden, there are always a few veronicas here and there. Drought-tolerant, low-maintenance and popular with bees, they are durable plants for early summer and make beautiful cut flowers. In my crown is a pale pink sport of V. longifolia ‘Eveline’ that seeded itself, but division of veronicas is a more reliable means of propagation.