I’ve been meaning to write this blog for years, but it took a global pandemic – and the fact that this is National Pollinator Week – to spur me into action. Because in a pandemic we need essential workers, and on this planet there are no workers more essential than pollinators. Think of it: in all flowering plants not pollinated by wind (grasses and many trees are wind pollinated), bees, buterflies, moths, birds, beetles, ants and other insects are responsible for transferring pollen from a flower’s male anthers to the receptive female stigma, ensuring fertilization of the ovum, the creation of fruit and later the ultimate dissemination of seed. Without pollinators, the world as we know it would be as it was more than 135 million years ago: boring. No need for colour, since grasses and birches and pines don’t need to wear flashy hues to have the wind disperse the pollen the produce. No need for flower fragrance, since the wind doesn’t need to be lured to flowers like moths to a nocturnal species. And wind pollination is so wasteful! Look at how many male white pine cones fall to the ground in the evolutionary effort to pollinate the receptive female cones. (This is my dock on Lake Muskoka north of Toronto, by the way).

No, insect pollination was a giant step forward, beginning with plants that looked vaguely like modern magnolias, likely fertilized by beetles. (I couldn’t find any beetles so substituted honey bees on Magnolia grandiflora, below).

Bees evolved initially from wasps. The earliest honey bee ancestors emerged in Asia roughly 120 million years ago. Bumble bees arrived on the scene between 30 and 40 million years ago. Modern honey bees and bumble bees, like those below on globe thistle, are the descendants of an ancient lineage of insect pollinators

As gardeners, we sometimes forget that there was a time when the natural world did not revolve around us. It got along just fine without Homo sapiens. In fact, there are quite a few people who think earth fared much better without humans, but then consciousness and evolution have given us the ability to perceive our achievements and actions with feelings of pride tempered by a growing sense of guilt. Climate change, conservation, overpopulation – they are all serious issues today, but that’s not what I’m focusing on here. Instead, I’d like to write a little love letter to the workers in earth’s most essential essential service: pollinators. Goodness knows I’ve spent enough time courting them over the past three decades and more. Here’s one of my Toronto Sun columns from 1997.

And here’s a story I proposed and wrote on urban beekeeping for the now-shuttered Organic Gardening magazine in 2012.

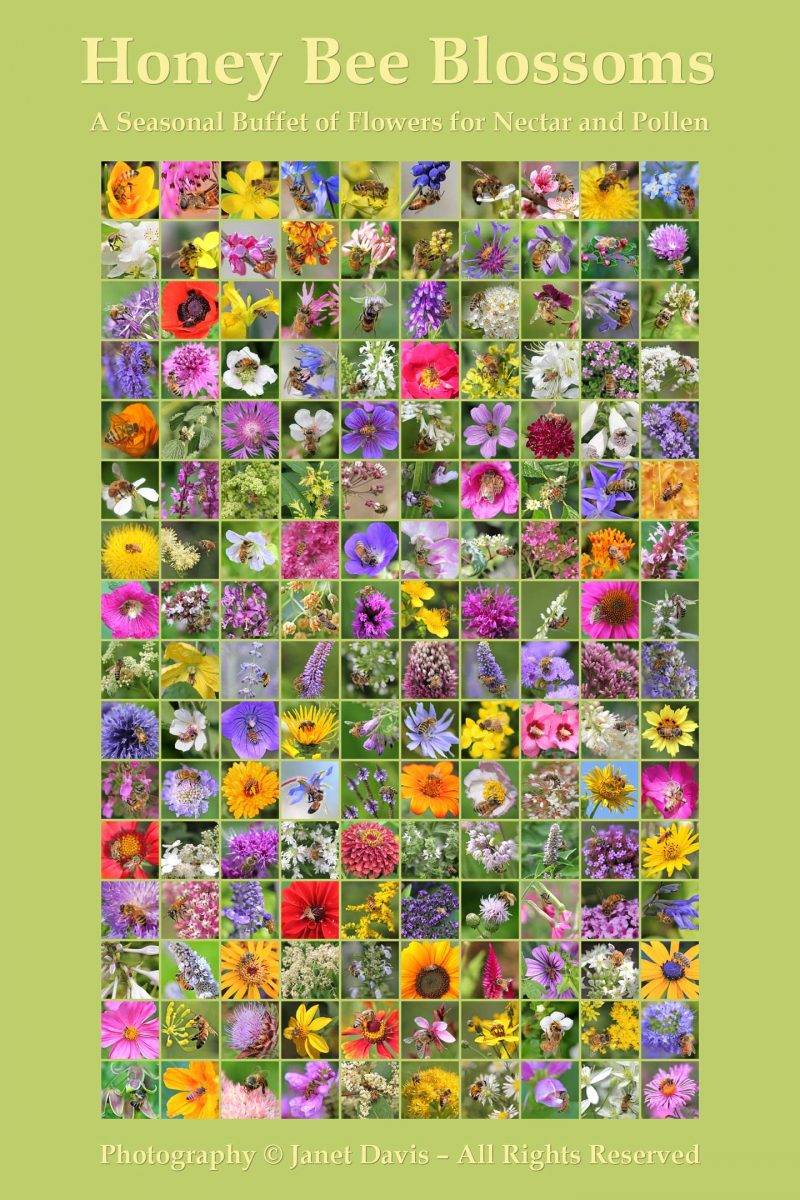

Researching nectar- or pollen-rich flowers for beekeepers for that story and finding very little in current literature launched a multi-year focus on honey bees and their favourite plants. Out of it came a quite spectacular poster……

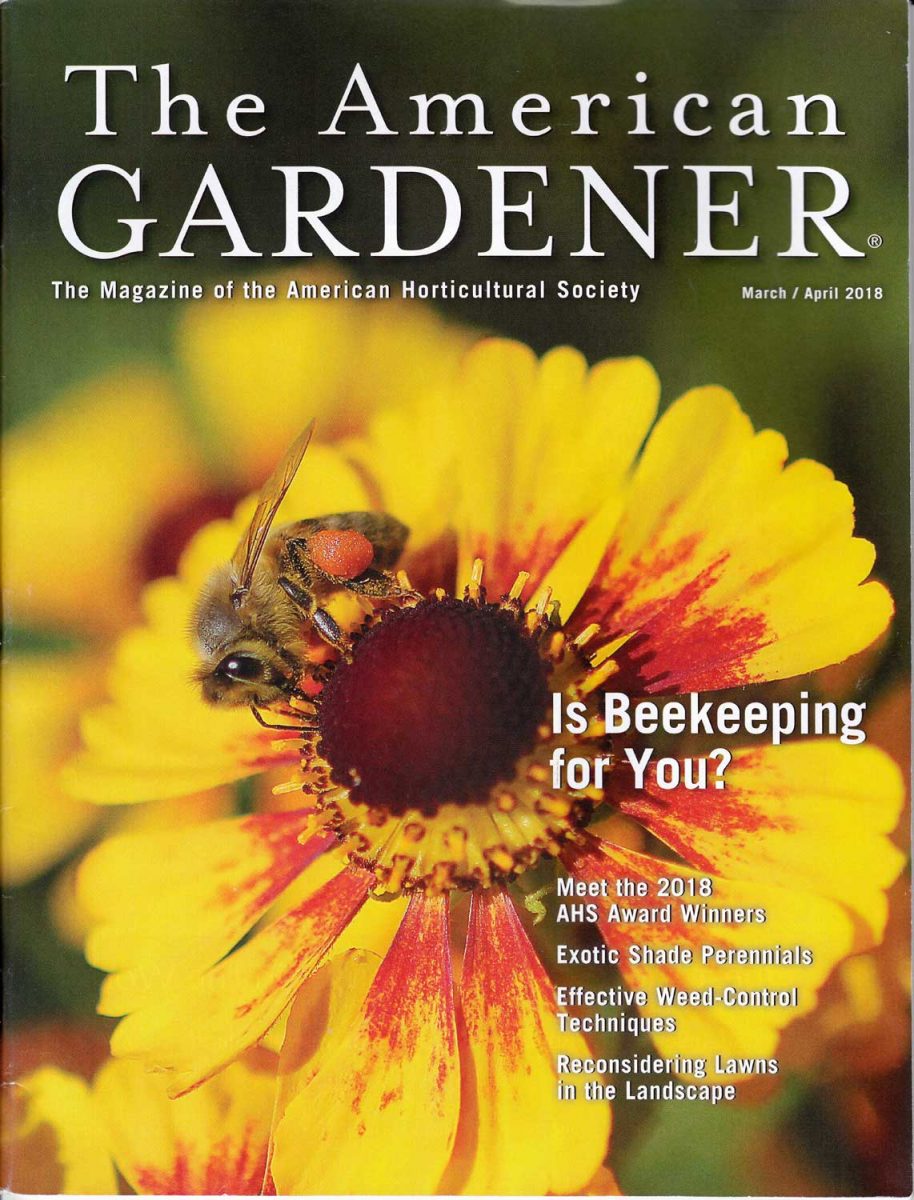

….. and the occasional magazine cover.

In time, I amassed such a large inventory of honey bee imagery (like the forget-me-not, below) that I decided to create an online photo library devoted just to them. If you’d like to have a browse, it is located here.

I have written stories about beekeepers, including my friend Tom Morrisey in Orillia, Ontario, below. This was my blog on his late summer honey harvest at Lavender Hill Farm.

My beekeeping pal Janet Wilson out in British Columbia drove me to her hives in a blackberry thicket on a farm, and let me photograph her checking on the hives.

When I was on safari at Kicheche Camp in Laikipia, Kenya in 2016, I loved spending time with the camp’s beekeeper William Wanyika, and learning how he does his work.

At Toronto Botanical Garden, I photographed the beehives and the student beekeepers….

….. and later that year I returned to photograph the honey harvest.

I enjoyed paying attention to nectar guides, the markings that plants have evolved to show pollinators exactly where to look for nectar and pollen. The European horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum), below, is an excellent example. Flowers with fresh nectar exhibit a yellow blotch; as the markings darken from orange to red, the bee knows that the flowers are old and no longer yielding nectar.

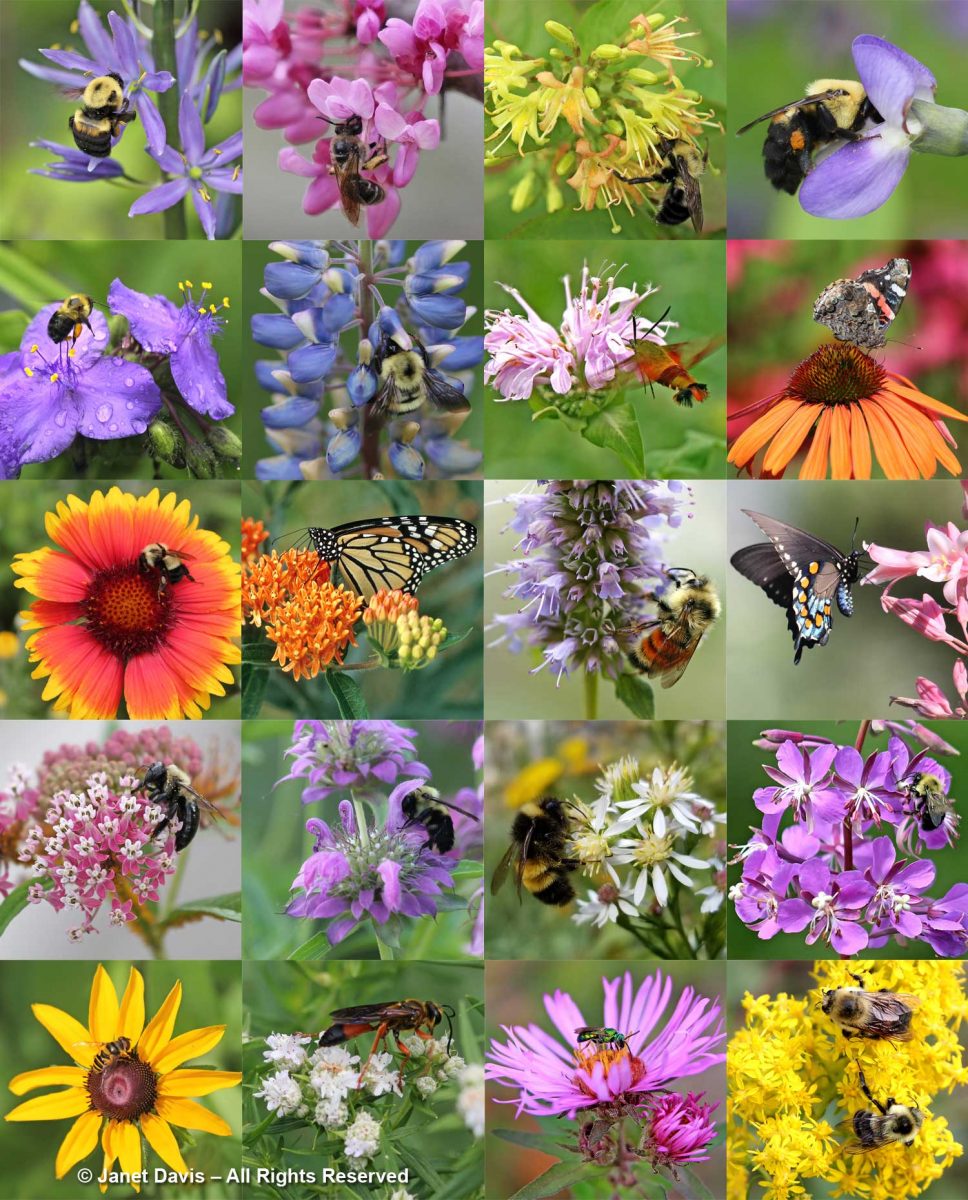

But as much as I appreciate the work that honey bees do, I have always understood that in North America, European honey bees (Apis mellifera) are very much domestic agricultural animals. They may be feral in places warm enough for them to overwinter, but in much of the continent they must be “kept”. Wild bees, or native bees, on the other hand, have co-evolved with our North American flora. Many of them are adaptable to a number of different plant species; they’re called “generalists”. Here is a montage I made of native North American bees and butterflies on native North American plants.

Other bees are “specialists”, requiring the nectar or pollen from one, or just a few, types of plants. The North American squash bee (Peponapis pruinosa) is one of those, spending its short life acquiring food from the flowers of native squash plants, like the one below.

On vacation in Arizona, I was interested in the specialist native Diadasia australis bees who forage solely on opuntia cacti, like this Engelmann’s prickly-pear (Opuntia engelmanii).

At home, I have come to know my local native vernal or spring bees, like the polyester bee (Colletes inaequalis), shown below on early-flowering willow (Salix).

But I’ve been bemused in the past few weeks by native bees paying no attention whatsoever to my native plants and instead finding their sources of carbohydrates and protein in the nectar and pollen of non-native plants, such as the bicoloured sweat bee Agapostemon virescens working the wine-red flowers of European knautia (Knautia macedonica) in my garden, below….

… and a plethora of native pollinators, including the Eastern tiger swallowtail, avidly foraging on my neighbour’s Chinese beauty bush, Kolkwitzia amabilis, below.

But some plants don’t need pollinators. While I was videotaping the June plants above, the birds were squabbling noisily over the first ripening serviceberries (Amelanchier sp.) nearby. (I photographed the one below on the High Line one June.) I was curious that in all my years observing my serviceberries and their clouds of tiny blossoms, I haven’t seen any pollinators attending the plants. How could I have such an abundance of early summer fruit? Scientists have shown that several species of Amelanchier have evolved “apomixis”, bypassing sexual reproduction, meiosis and cell division entirely – thus no need for insect fertilization. In apomicts, the ovum in the flower divides parthenogenically.

I adore bumble bees (Bombus species), and I’ve spent years trying to identify the ones I see in my gardens and even the species I encounter during my travels. You probably won’t be surprised to learn that I have a large photo inventory of bumble bees online. Below is my favourite of all, the brown-belted bumble bee (Bombus griseocollis). Isn’t that the perfect name?

And I do have a soft spot for Toronto’s (un)official bee mascot, the bicoloured agapostemon (A. virescens), shown here foraging on purple coneflower in my garden.

Though many people dislike them for their wood-boring trait, particularly if it happens to their pergolas or sundecks, I love watching carpenter bees (Xylocopa virginica) using that strong tongue to bore into the corollas of certain flowers, like the Nicotiana mutabilis, below. Biologists call that “nectar robbery”, i.e. the bee is effectively bypassing the evolutionary pact between bee and pollinator to gain the reward without transferring pollen from one flower to another.

At the Toronto Botanical Garden, where I’ve contributed my photography as seasonal galleries, I spent a few seasons tracking pollinators on the plants, and made a musical video to celebrate them.

My city garden in Toronto was designed as a pollinator garden, too. It contains both native and non-native plants. I’ve shown this video a few times in my blog, but here it is again throughout four seasons.

And at my cottage on Lake Muskoka, I look upon almost every plant in my meadows, garden beds and planters as a chance to invite bumble bees, solitary bees and hummingbirds to sup on the mostly native plants I provide for them. (Please note that the vernonia should be V. noveboracensis).

So to celebrate National Pollinator Week, I would like to encourage all of you to think about your relationship as gardeners to the natural world. Should your garden really be all about you and what you like? Or do you agree with me that we should also consider that….