My 7th fairy crown for late May was created at our cottage on Lake Muskoka, a few hours north of Toronto. It features native wildflowers and fruit: red-flowered eastern columbine (Aquilegia canadensis), common blue violets (Viola sororia), wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium), the poet’s narcissus (Narcissus poeticus var. recurvus) and a little weed for good measure, yellow rocketcress (Barbarea vulgaris).

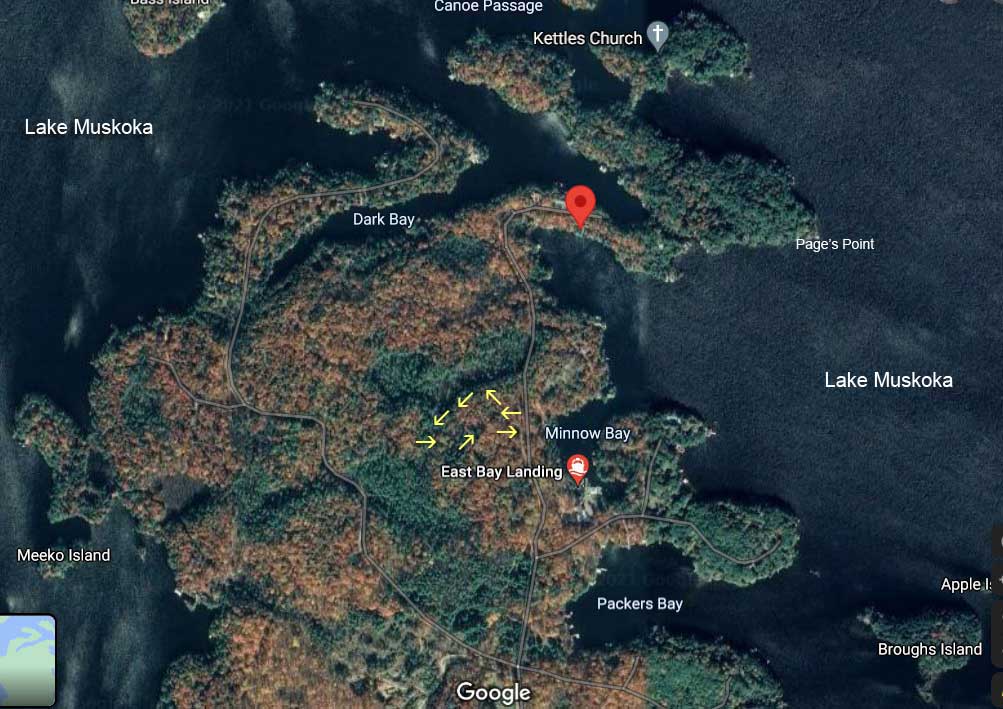

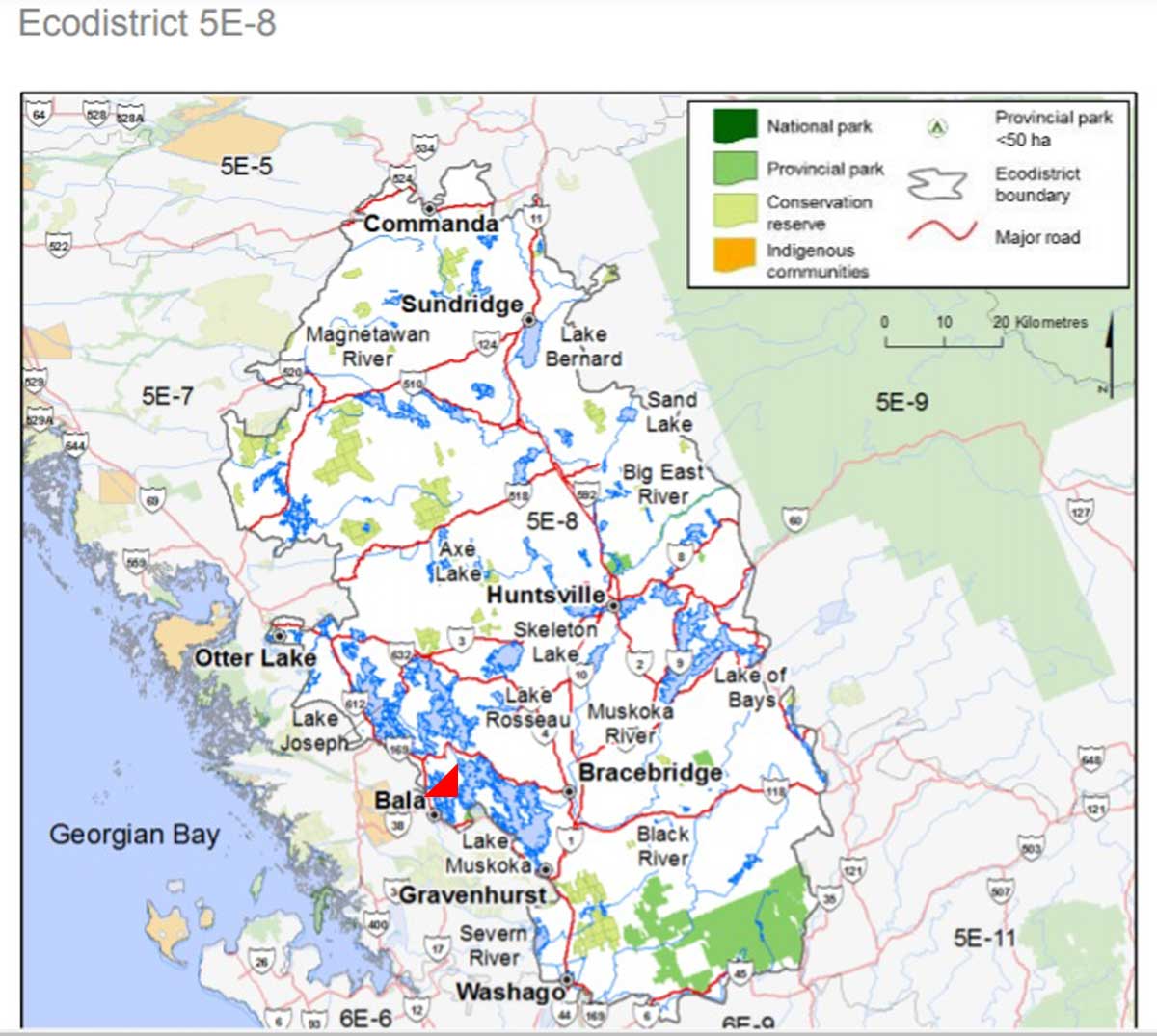

If my city garden takes a somewhat naturalistic approach to gardening, it is nonetheless situated in a traditional urban neighborhood. It might be the most flowery front garden on the street, but I’ve worked to make it fit in with the lawns up and down the block by having a hedge as a side boundary; by retaining old clipped boxwood shrubs on either side of the front stairs; and by paying attention to pleasing floral succession, from the earliest snowdrops to the last asters. And my neighbors do love it. In contrast, the meadows and garden beds I created atop Precambrian bedrock at our cottage on Lake Muskoka a few hours north of Toronto are truly wild-looking – and there’s no need to fit in with any neighbors. (I wrote about gardening at the lake in my extensive 2017 blog titled ‘Muskoka Wild’.)

I don’t grow tulips there — they’re just not right for the lake — but my fairy crown for May 20th features the last daffodil of the season, the poet’s daffodil (Narcissus poeticus var. recurvus).

Daffodils grow amazingly well in the acidic, sandy soil here since they love to dry out in summer, popping up each spring amidst the big prairie grasses and forbs.

Besides the poet’s daffodil, one of my favourites is the highly scented Tazetta variety ‘Geranium’, below.

My grandchildren have all experienced nature on Lake Muskoka. This is Oliver exploring another perfumed daffodil, ‘Fragrant Rose’.

And there is nothing more satisfying than a bouquet of perfumed daffodils on the table in April or May.

On many occasions, I’ve tucked a bunch of daffodils in my bag as I head back to the city.

Daffodils flower concurrently with our little native common blue violet, Viola sororia.

Viola sororia is native to Muskoka, as it is to much of northeast North America. It doesn’t take up a lot of room and grows wherever it pleases, but always with a little shade and moisture at the roots.

Apart from violets, the landscape here features a large roster of native plants, including the lovely eastern columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) that pops up in the lean, gravelly soil where many plants might struggle. I try to sow seed of this species, being careful to leave the seeds uncovered since light is necessary for germination.

But wild columbine is very particular about where it wants to put down roots, and always surprises me when I see the first, ferny leaves pop up in a new location in spring.

Hummingbirds are said to enjoy the dainty flowers of eastern columbine, but I confess I’ve never seen them doing so. I would have to lie in wait on rocky ground by the shore, not as much fun as sitting comfortably on my deck watching them fight over the ‘Black & Bloom’ anise sage (Salvia guaranitica).

Muskoka and wild blueberries just go together naturally, and somebody’s grandmother always made the very best wild blueberry pie in August. In our family, it was my husband’s mother, and she taught her grandkids her secret recipe, including my daughter. So I’m always happy to see the queen bumble bee pollinating those first wild blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) flowers in May.

But just in case the chipmunks find our berries before we do, we always make a stop at the wild blueberry stand on the way to the cottage from town.

Wild strawberries (Fragaria virginiana) bloom in Muskoka now, too, and on parts of my path above the lake they form a perennial groundcover so dense that I am sometimes afraid to step into their midst, lest I damage them.

But there are always enough strawberries ripening months later to make my grandkids pause on their way to the lake to sample the fruit…

…tiny, admittedly, but oh-so-sweet and juicy.

Similarly, May is when the dark-pink flowers of black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata) adorn the shrubs in the shade of the white pines along the lakeshore. The deep-purple fruit will ripen in August and though somewhat seedy, it is sweet and good for eating raw or baking.

There’s a native serviceberry here at the lake too, but don’t expect to see billowing clouds of white flowers like those big species further south. Its Latin name Amelanchier humilis gives a clue as to its shape, “low, spreading serviceberry”. Still, native andrena bees love nectaring on it in May, as do the bumble bee queens, which nonetheless must remain wary of crab spiders looking for their own meals.

My crown’s golden jewels are flowers of the common European weed in the mustard family, yellow rocketcress (Barbarea vulgaris). In Europe, it’s called ‘rocket’ or ‘bittercress’, suggesting a strong-tasting, edible green. Indeed, my foraging friends would recommend picking the basal leaves as they emerge in spring or the rapini-like flower buds (raab) to cook in recipes. Failing that, just wait for the mustard-yellow flowers to appear and wear them in your fairy crown!

I use my smallest vases to display these delicate blossoms of spring on the table – a welcome celebration of nature’s return to the shore of a lake that was thick with ice just weeks earlier

********

Want to see more of my Fairy Crowns?