Day 9 of our voyage with Adventure Canada found us 168 km (104 mi) south of our last port, Uummanaq, and 100 km (62 mi) west of spectacular Ilulissat in the small town of Qeqertarsuaq, Greenland (population 870 in 2020).

“Qeqertarsuaq” is the Kalaallisut word for “big island” – meaning Disko Island, on which the town is located. In fact, apart from the tiny village of Kangerluk, it’s the only town on Disko Island. Founded in 1773 by Danish whaler and merchant Svend Sandgreen, it was originally called Godhavn (“good harbour”). However artifacts have been found from a Paleo-Eskimo settlement dating back 5,000-6,000 years.

Looming behind Qeqertarsuaq are red basalt cliffs almost 3,000 feet tall, with layered lava benches. This geological formation is relatively young, formed by volcanism some 60 million years ago (the Maligât Formation), compared to the Precambrian bedrock (1.6+ Ga) we see layered at the front in the photo below. Interestingly, Disko Island is famous for its rare, non-meteoric, naturally-occurring iron or cohenite, which forms when molten magma invades a coal deposit – in this case emerging through sediment in a very deep lake.

Today the town of Qeqertarsuaq is the home of the Arctic Research Station (Artiskstation) Greenland campus, for the University of Copenhagen. You can see the main building on the right up the road from the dad bicycling his kids past the bedrock, below.

We saw students from the Arctic Station working on a research project. Much of the monitoring here is related to GEM – Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring – a long-term monitoring program operated by Greenlandic and Danish research institutions. The focus of GEM is on Arctic ecosystems and climate change effects and feedbacks in Greenland.

Like Sisimiut and Ilulissat, Qeqertarsuaq features rows of colourful houses. I especially liked the subtle shading here.

Meltwater ponds were abundant at the base of the hill.

In a town where fishing is the main industry, it’s not unusual to see fishing nets drying along with curtains in the sunshine.

We got close to the land in Qeqertarsuaq, beginning our trek crossing the bridge at the outlet of the Kuussuaq River under the bridge.

Kuussuaq in English is Red River (Røde Elv in Danish), because of the reddish, lateritic soil that washes down from the volcanic rock underlying the Lyngmark Glacier into the river and out into Disko Bay.

The craggy, mossy hillside was dramatic…..

…. and the ground in places was littered with rocks washed down from the glacier, i.e. “glacial outwash field”.

The Kuussuac River is a braided river, with water rushing down through deep crevasses from the Lyngmark Glacier. I can see purple patches of dwarf fireweed on the riverbank below.

We stood for a while beside the Qorlortorsuaq waterfall – a phrase which is redundant in Greenlandic, since the word actually means “big waterfall”.

On my trek, I had to stop and photograph plants, of course – many of which were now familiar since our first day in Iqaluit. This is dwarf birch (Betula nana).

Clustered lady’s mantle (Alchemilla glomerulans) grew along a stream.

I love the Inuit lore associated with the twisted styles on the seedheads of Dryas integrifolia, the entire leaf mountain avens. In Kalaallisut and Inuktitut, this plant is called malikkaat because it designates practices associated with the passing seasons. In Nunavut, Canada, according to oral history, “When the seed heads are tightly twisted, caribou skins are too thin to make clothing. As the seed heads untwist, caribou skins are suitable for women’s clothing. When the seed heads are fully open, caribou skins are suitable for men’s clothing.”

An Arctic fritillary butterfly (Boloria chariclea) foraged in the meadow.

The verdant Blæsedalen Valley or Itinneq Kangilleq beckoned ahead, but our time was running out.

I managed a few images of the amazing irregular basalt columnar formations forming the cliff walls in certain places. As you might expect from its volcanic origin, there are also geothermal springs in this area, especially a little further up the coast at Unartorssuak where water issuing onto the beach below a large erratic rock (Termistorstenen) is between 13-16C (55-60F).

If we’d had more time there, I would have loved to keep hiking upwards to Kuannit, the place where locals find the biennial herb Angelica archangelica (“kvan” in Danish, “kuanneq” in Kalaallisut) growing and gather it as a vegetable and medicinal. Alas, no time. I found the plant pictured below growing in Vancouver’s UBC Botanical Garden traditional herb garden.

It was time to retrace our steps along the Kuussuaq River and head back towards Disko Bay.

Beyond the outwash field and the drop-off was the famous black sand beach of Qeqertarsuaq.

On our way through town, we stopped at the little museum. In 1840, it was the home of the colonial inspector; today it houses a nice display of traditional artifacts and clothing,

…. carvings and modern art works….

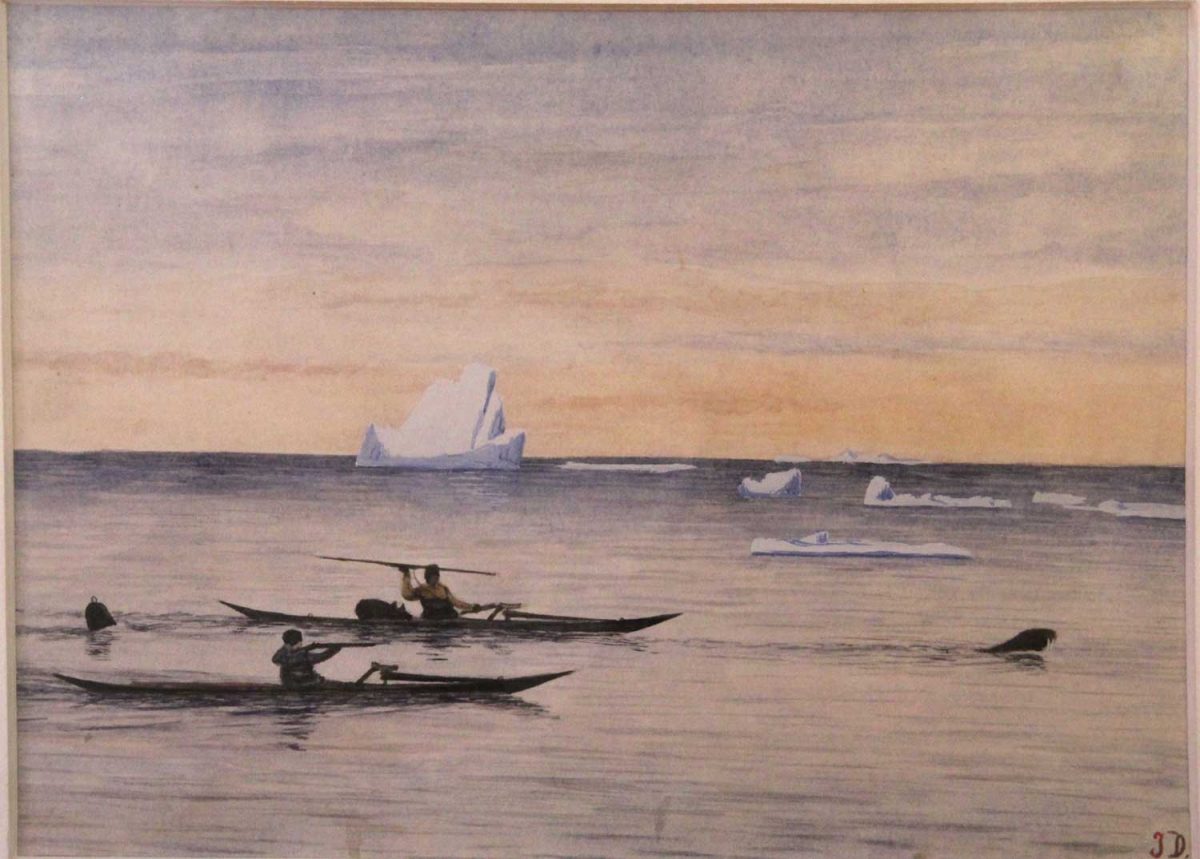

….. as well as a large collection of the work of Greenlandic hunter and painter Jakob Danielsen (1888-1938) who chronicled the hunting life a century ago.

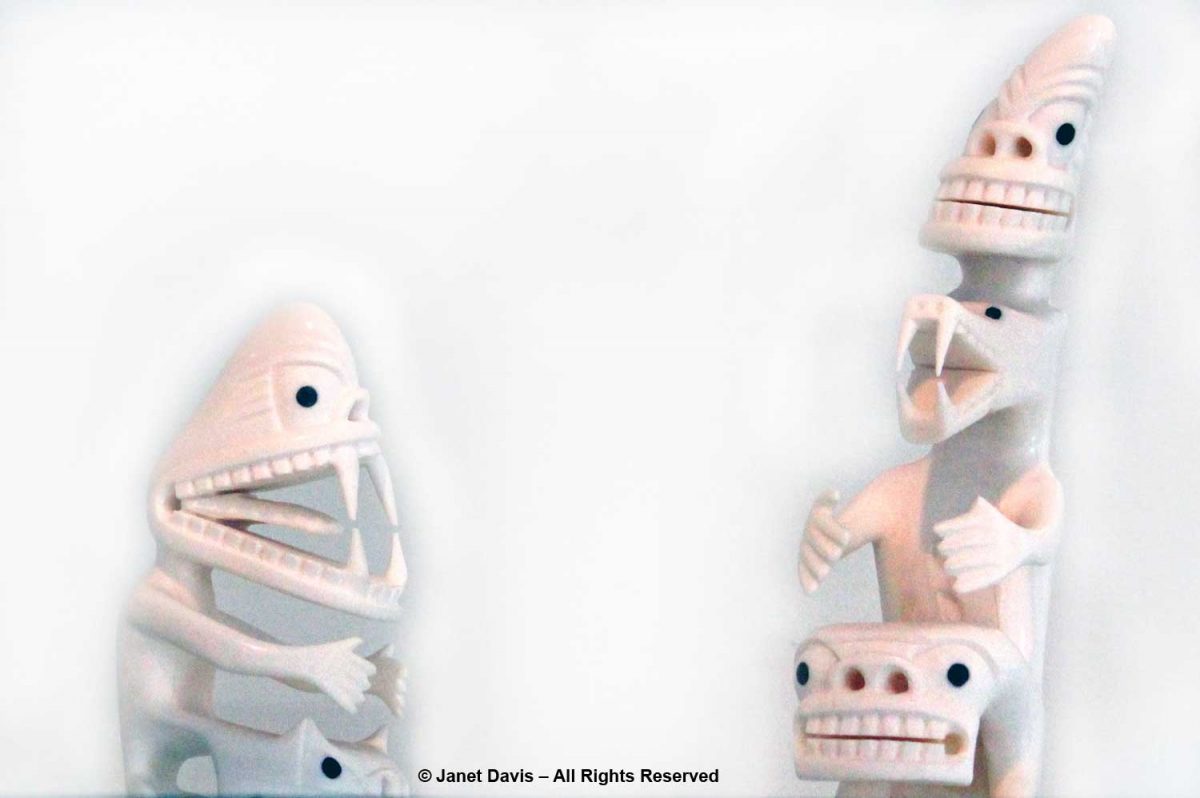

There was an exhibit of tupilaqs in the museum, too. In the Greenland Inuit tradition, a tupilaq is an avenging monster created by a shaman and placed into the sea to seek and destroy a specific enemy. But deploying a tupilaq was risky because the enemy target could have stronger power and send the tupilaq back to attack its maker. Ancient tupilaqs were made of perishable materials in secret places; modern ones are fabricated from narwhal and walrus tusk and wood or caribou antlers.

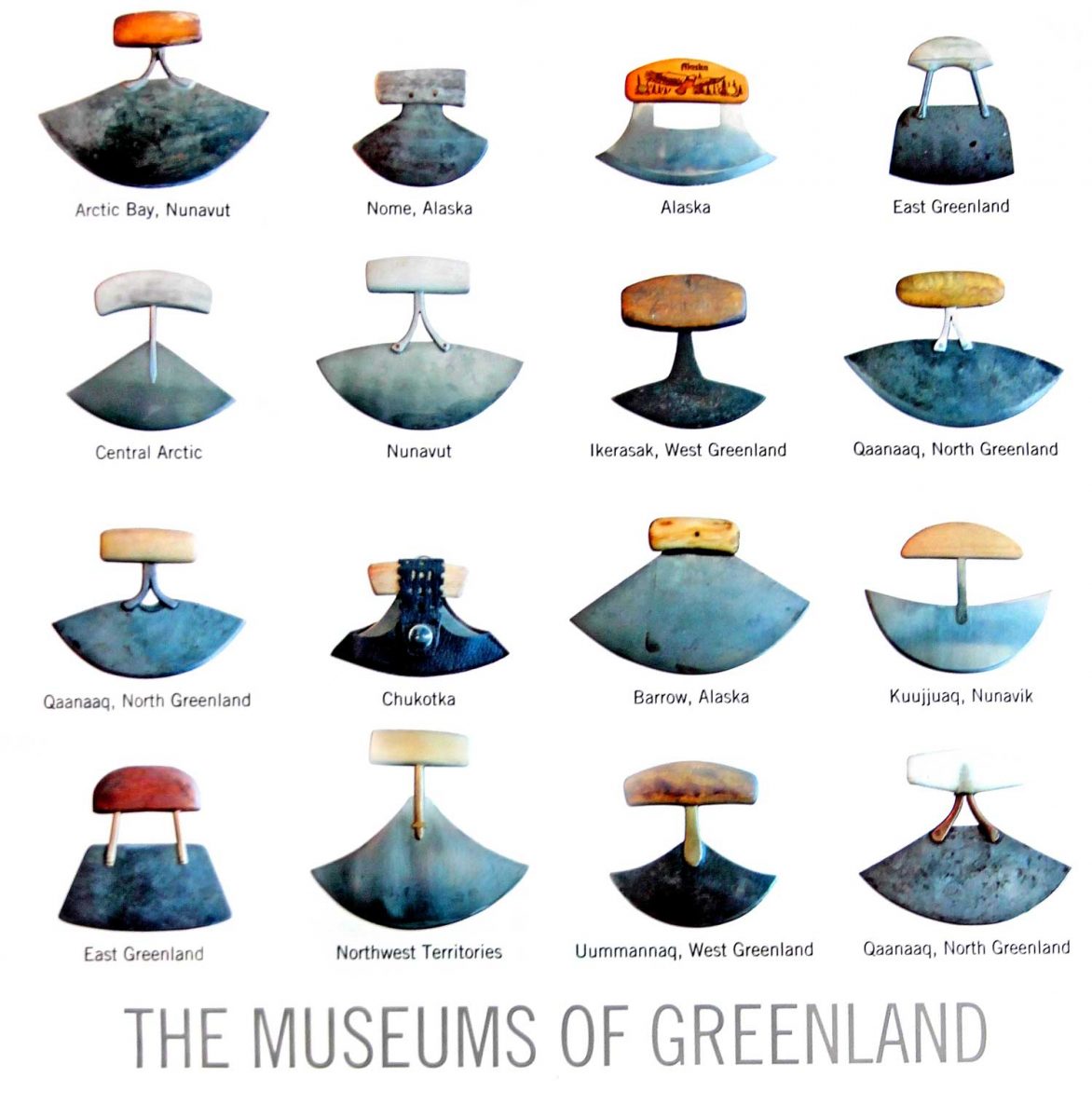

To honour the museum’s collection of ulus or “women’s knives”, I bought a postcard, which the clerk packed in a beautiful…..

….. shopping bag decorated with a wonderful collection of these knives from all around the Arctic. In Nunavut, the knife is called an ulu; in Greenland, it’s called a sakiaq; in the Northwest Territories, it’s an uluaq. The knife is used to skin and clean animals, cut a child’s hair, slice food, and even trim the blocks of ice used to build an igloo.

We headed back to the ship. Not long after lifting anchor, we were rewarded with another whale sighting — this time a humpback (Megaptera novaeangliae).

That night, we were treated to one of Adventure Canada’s onboard traditions, the “talent show”. Hawaiian-themed, it featured performances from both passengers and crew. Here the resource staff offered their own take. From left, culturalist (Labrador-born Inuk) Jason Edmunds, Adventure Canada president Matthew Swan (now retired), “the entertainer” Tom Kovacs, field botanist Carolyn Mallory, Inuit art specialist (behind) Carol Heppenstall (now retired), seabird biologist Dr. Mark Mallory and expedition leader Stefan Kindberg (now retired).

Though we didn’t sing or recite Scottish ballads or play guitar, Doug and I got into the act with tacky dollar-store leis.

Best of all, the evening ended with a gorgeous Arctic sunset.

********

This is the 8th in my series on the Eastern Arctic. Here are the 7 previous blogs (only two remaining):