One of my gardening life goals has been to travel to Austin, Texas in April to see the bluebonnets in flower, those much photographed sheets of azure-blue carpeting the ground in parts of west Texas. A few weeks ago, I managed one of those goals – to travel to Austin – and I had a tiny whiff of the other – those bluebonnets – when I joined almost a hundred other garden bloggers at our annual Fling, during which we tour around public and private gardens and nurseries to get a flavour of the best horticulture and design from each host city. The list of gardens included the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in southwest Austin. The Center, of course, was the dream of Claudia Taylor Johnson, aka “Lady Bird” (1912-2007), one she fulfilled after returning home to Austin from Washington DC when her role as First Lady with President Lyndon Baines Johnson ended in 1969.

But even before LBJ assumed the presidency in 1963, following John F. Kennedy’s assassination, Lady Bird had proved herself a capable businesswoman, using her own family inheritance to buy a few small radio and television stations that later parlayed her $41,000 investment to $150 million. But during her time in the nation’s capital, “beautification” was her passion, and by that she didn’t just mean gussying up outdoor spaces with pretty flowers, but thinking hard about improving the aesthetics of the roads and highways so many Americans spent hours driving on and through each day. She also advocated for the preservation of national parks. In Washington itself, Lady Bird, with the help of philanthropist Laurence Rockefeller, launched a project called Society for a More Beautiful National Capital; it resulted in a significant planting program for the capital: dogwoods, oaks, crape myrtles, and more cherry blossoms for the Washington Monument area, below.

More importantly, in October 1965, the federal Highways Beautification Act (proposed by LBJ but known unofficially as Lady Bird’s Bill) was passed, effectively controlling the proliferation of large billboards, lighting, junkyards and other eyesores and advocating wildflower planting along the nation’s highways. In an appreciation column after her 2007 death, the Washington Post said of Lady Bird’s influence on her husband’s presidency: “It was but one of 150 environmental laws, including the landmark Clean Air Act, enacted with her vigorous support during the Johnson administration from 1963 to 1969. She was a patron saint to the National Park Service.” But for Texans, her landmark contribution was the co-founding, with actress Helen Hayes, of the National Wildflower Research Center in 1982. Its first 60-acre site was in East Austin, but its popularity with the public dictated a 1995 move to the current site in southwest Austin, now expanded to 279 acres. In 1998 it was renamed the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center and was incorporated into the University of Texas at Austin in 2006. It now fulfils its mandate of promoting and conserving Texas native wildflowers, grasses, trees and shrubs and acting as the largest online database of North American native plants (it actually managed to snag the online URL www.wildflower.org) while providing a lovely venue for conferences, weddings and other social events.

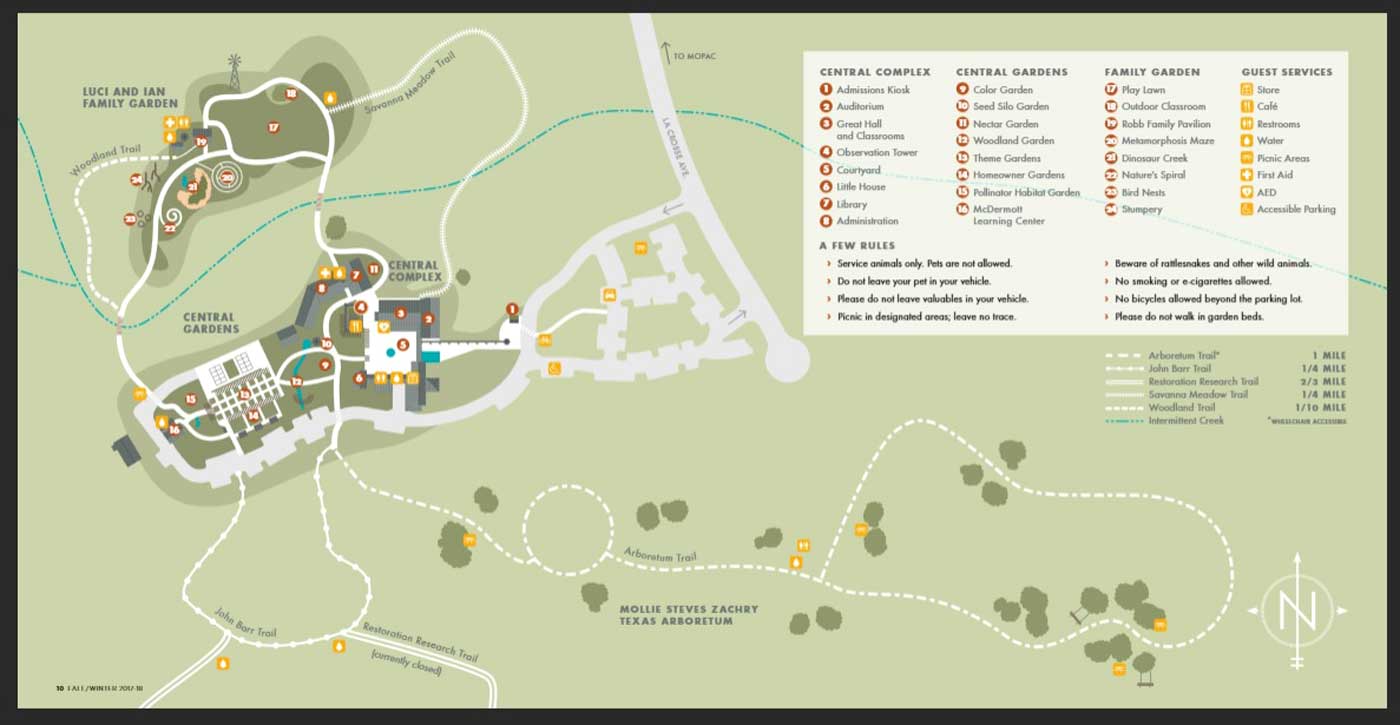

And here I was, ready to explore its 9 acres of cultivated gardens. (In actual fact, I had signed up for an early morning photo seminar, but the weather forecast was dire so I made the decision to photograph outdoors before the rain started.)

I began in the courtyard near the Central Complex buildings, where a little “hillcountry spring” irrigates the plants.

I walked around the buildings in the central complex, noting the big muhly grass (Muhlenbergia lindheimeri) and a pretty pink-and-white cultivar of autumn sage (Salvia greggii ‘Teresa’) that the center itself propagates and sells, on behalf of its discoverer, David Steinbrunner, to raise funds.

I passed the Color Garden, created in memory of Leslie Turpin, by his son Ian Turpin and daughter-in-law Lucy Baines Johnson Turpin.

Purple coneflowers (Echinacea purpurea) and blackeyed susans (Rudbeckia hirta) reminded me of my own Ontario meadow garden. I would give anything to be there when those standing cypress (Ipomopsis rubra) in the background sent up their bright-red flowers!

This was the Edible Garden. Did you know that mealycup sage (S. farinacea) and evening primroses (Oenothera speciosa) are edible?

Walking past drifts of blue and white mealycup sage made me appreciate anew that little annual workhorse cultivar ‘Victoria Blue’. It became so popular, we grew a little bored with it, but I don’t recall it ever having quite so commanding a presence as these tall sages.

Strolling through the gardens outside the auditorium, I caught a glimpse of the audio-visual screen and felt momentarily guilty at being outside – but I could already hear thunder rumbling in the distance.

The central complex buildings all have adjoining gardens of native wildflowers, so you don’t have to wander far afield to see beauty.

There was lots of colour here in the Nectar Garden, where Prairie verbena (Glandularia bipinnatifida) was looking lovely.

I took the Savanna Meadow Trail leading to the 5-acre $5.3 million Luci & Ian Family Garden donated by Ian Turpin and Lady Bird’s daughter, Luci Baines Johnson Turpin.

This was a useful reminder to visitors to stay on the pathways.

Native wildflowers have been used in designed areas adjacent to the Play Lawn in the Family Garden.

This pretty combination of Texas yellowstar (Lindheimera texana) and mealycup sage (Salvia farinacea) caught my eye. Love those yellows and blues together!

This is Engelmann’s daisy (Engelmannia peristenia).

And this is Engelmann’s prickly-pear (Opuntia engelmannii), below. Both of these plants were named for the German-born botanist and doctor Georg Engelmann, who emigrated to Baltimore in 1832, eventually setting up a medical practice in St. Louis with his young German wife and doing his botanizing on vacations from his practice. He was despondent after her death in 1879, when he was approached by Charles Sargent of Boston’s Arnold Arboretum to accompany him on a trip to the Pacific coast, where, at the age of 70, he collected the plants that now bear his name.

This gorgeous flower is Texas rock rose or swamp mallow (Pavonia lasiopetala).

I did find a few bedraggled bluebonnets (Lupinus texensis), but the big show had happened in March and early April.

There were scattered Texas Indian paintbrushes (Castilleja indivisa) around, too. Though I had a nicer photo of this plant, I included the one below because it illustrates a peculiarity of this species and all members of the genus. Their specialized roots, called “haustoria”, wander below ground until they touch the roots of neighbouring plants, often grasses, whose roots they then penetrate to secure nutrients and water. Members of the hemiparasitic family Orobanchaceae, paintbrushes do photosynthesize themselves, but they use this method to augment their own metabolisms.

The prime host plant for Texas Indian paintbrush, not surprisingly, is nitrogen-fixing Texas bluebonnet, a partnership beautifully illustrated in the photo of Lady Bird Johnson below.

I think blanket flower (Gaillardia pulchella) was the most abundant wildflower I saw in my 4 days in Austin, with highway edges spangled red and yellow like this.

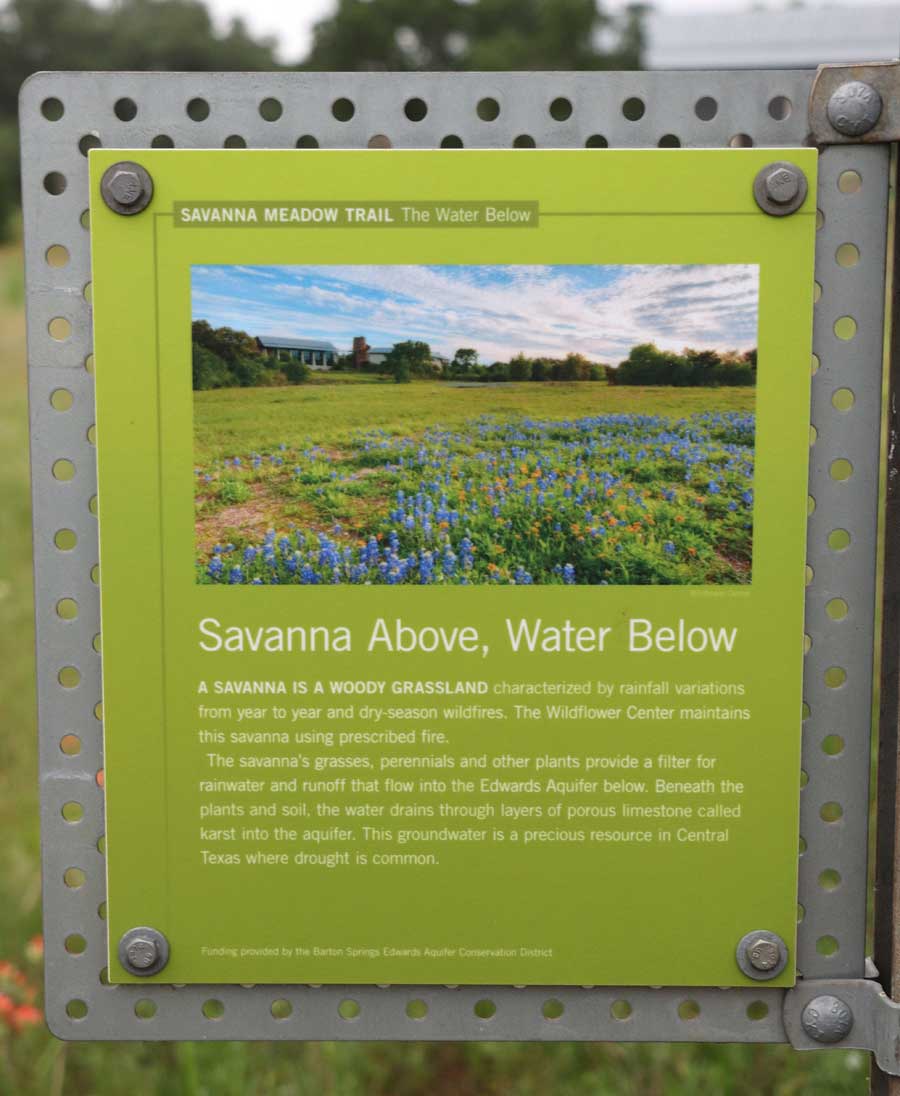

The sign below highlights the center’s focus on education and ecology. A savanna, of course, is a grassy plain studded here and there with the occasional tree, but here, the savanna is managed with prescribed burns to control the incursion of too many woody species.

I was excited to find sprawling antelope horn (Asclepias asperula), just one of Texas’s thirty-six native milkweeds – a fine feast for monarchs winging their way north from their wintering grounds in Mexico.

Some wildflowers I knew, like Mexican hat (Ratibida columnifera), below…..

….. but most I didn’t, such as silverleaf nightshade (Solanum elaeagnifolium)…..

….. and Texas prairie parsley (Polytaenia texana).

It was fun to see white sage (Artemisa ludoviciana) growing with big muhly and prickly-pear, since so many gardeners are familiar with the cultivar ‘Silver King’.

I was unaware, when I walked into the Family Garden, that it had been designed by my friend W. Gary Smith with TBG Partners. An artist and landscape architect who has remained firmly in touch with his inner child and the world of make-believe, Gary created a magical space here in Austin. First off, I noticed the massive windmill……

…. which I suppose is intended to demonstrate wind power, provided the kids work hard enough on the equipment to generate the energy needed to turn the blades!

I was happy to see red yucca (Hesperaloe parviflora) flowering here, because it had been the star of the Red Hills Desert Garden in St. George, Utah, which I’d visited and photographed a few days earlier. Shockingly (for a plant photographer), I had never even seen a hesperaloe before Utah and Texas, only to find it was one of the most common plants in the Austin gardens we visited!

Look how lovely those flowers are – and a lure for hummingbirds and butterflies, too.

The Robb Family Pavilion offers a bit of shade so kids can engage in crafts or picnic out of the hot Texas sun.

There’s a Dinosaur Creek here with “footprints” of actual dinosaurs whose fossil remains have been found in the region.

Nature’s Spiral features colourful walls (with tiles recycled from a dump) enclosing a spiral path that teaches children about the spiral shapes found in nature, including Fibonacci sequences!

The Stumpery is made from fallen cedar trees and is perfect for climbing.

The Giant Birds’ Nests were fashioned from grapevines and grasses.

And, as if preordained, it was right after exploring the birds’ nests that I heard my first Carolina wren singing in the forest, soon to be followed by the familiar song of a cardinal. Have a listen…..

The Karst Bridge reminds visitors that the center’s savanna sits on a karst landscape featuring porous limestone through which water percolates and is transported miles away.

Now I came to smaller scale gardens designed to inspire visitors to grow native plants on their own properties. This was the Tallgrass Meadow in the Ann and O.J. Weber Pollinator Habitat Garden, featuring lots of Texas parsley.

A nearby trellis featured the tropical-looking flowers of vigorous crossvine (Bignonia capreolata), which can be found climbing trees in damp pine woods in east Texas.

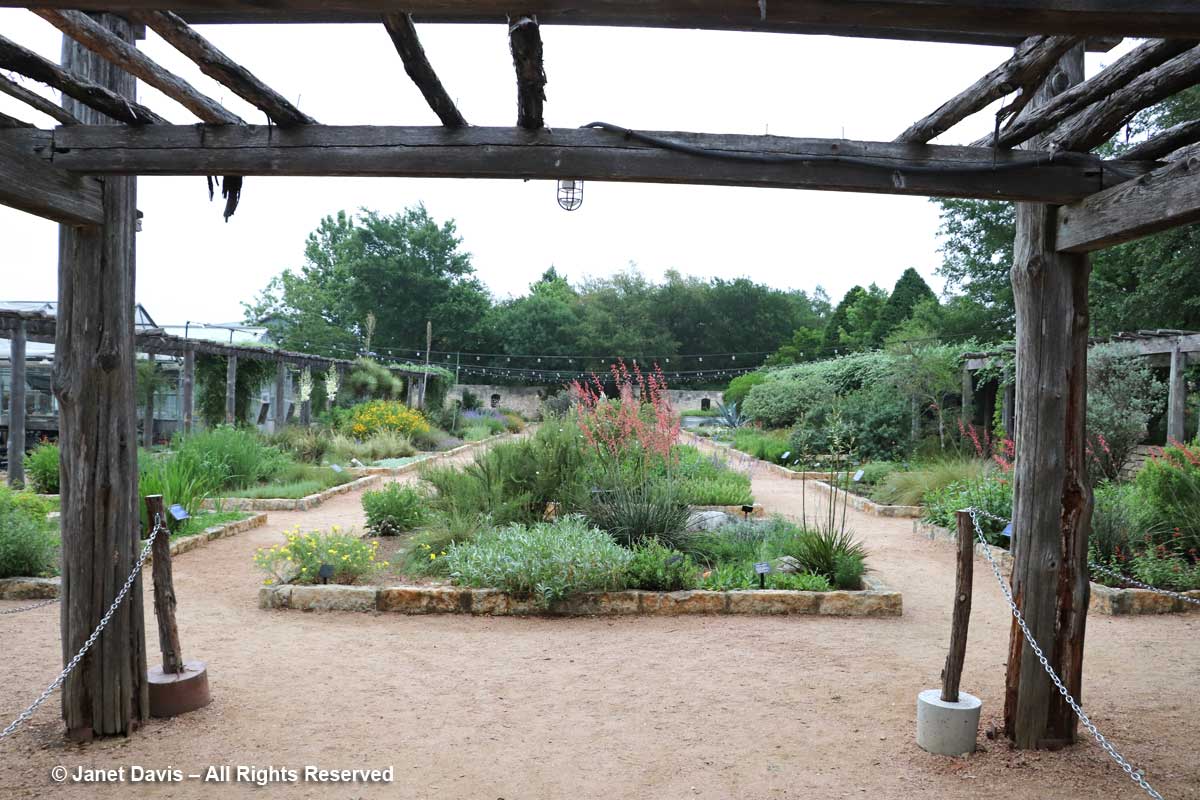

Thunder was closing in and a few raindrops had begun as I walked quickly into the Theme Gardens, 23 beds all surrounded by a low limestone wall, each demonstrating varieties and uses of plants for “weekend gardeners”. There is a fiber & dye garden, a night-bloomers-for-moonlight garden, a deer-resistant garden, a hummingbird garden (which would surely include red yucca, below, a hummer favourite!)….

…..and dry gardens featuring plants like this handsome agave ……

…. and cane cholla (Cylindropuntia imbricata var. imbricata).

I loved these big tank planters filled with autumn sage (Salvia greggii).

I could have stayed in the theme gardens for hours, but the rain was approaching and I made a dash back to the gift shop and Visitor’s Center. Moments later, the skies opened and we were treated to a Texas rainstorm – and not the 5-minute cloudburst typical of an eastern thunderstorm. No, no. This one went on long enough that our shoes and pant legs below our rain ponchos got sopping-wet and stayed soaked for the entire day! So, as a final memory of Lady Bird Johnson’s wonderful Wildflower Center, here’s a little taste of a true Texas gully-washer, with a serenade by the late Dee Clark.

A few days after visiting the center, I walked down Congress Avenue and stood on the bridge overlooking what used to be called Town Lake (a man-made reservoir in the Colorado River), but was renamed Lady Bird Lake following Lady Bird Johnson’s death in 2007. She had worked hard to beautify the lake and create a recreational trail system around its shoreline.

I will let Lady Bird Johnson sign off on today’s blog: “My heart found its home long ago in the beauty, mystery, order and disorder of the flowering earth. I wanted future generations to be able to savor what I had all my life”.