My tenth fairy crown for June 10th created at the cottage on Lake Muskoka features an array of flowers picked from my meadows and wildish garden beds. If it’s a little quiet-looking, that’s because it’s still very green in the meadows, and the plants that predominate, such as lupines and blue false indigo (Baptisia australis) are, well, solemnly blue. Along with those two, my crown has golden Alexanders (Zizia aurea), white nannyberry flowers (Viburnum lentago), white oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum superbum) and the tiny pink flowers of black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata). And, in an effort to reflect the bad with the good, there are some caterpillar-chewed oak leaves, courtesy of the spongy moth (LDD or gypsy moth) caterpillars.

In fact, it’s a time of year I think of as ‘June blues’; in reality, it’s more lavender-purple, but it’s remarkable that so many plants with similar flower color bloom simultaneously. I fashioned a bouquet one June, setting the finished product in the meadows where the lupines grow. In it were the lupines as well as false blue indigo (Baptisia australis), blue flag iris (Iris versicolor), pale lilac showy penstemon (Penstemon grandiflorus) and a few of my “weeds”, oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare) and buttercups (Ranunculus repens).

I grew the lupines from seed – a fairly complex operation that involved soaking the seed in warm water for 24 hours, then planting them in my sandy, acidic soil in a spot at the bottom of a slope that stays damp all the time. Fortunately, it worked and plants that were carefully transplanted and kept watered the first year have self-sown successive generations of new lupines that are very drought-tolerant. This is how they looked in the first few years, though now the big prairie species in the meadow have elbowed them to the margins. Though marketed as the eastern native wild lupine, L. perennis, my plants were in fact likely hybrids with L. polyphyllus from the west coast.

Nevertheless, they attract numerous queen bumble bees seeking to provision their nests in spring.

There is something so enticing about lupine flowers, so I like to focus on them with my camera to see what might be hanging out there, whether spiders….

…. or baby grasshoppers.

Blue false indigo (Baptisia australis) is a North American native plant whose pea-like flowers resemble those of lupine.

Bushy, it grows to about 4 feet (1.2 m) and is happy in my gravelly, sandy soil on a slope that gathers a little moisture. In autumn, the foliage turns an amazing gunmetal-gray and the seedpods shake with a noise like a rattlesnake’s tail. Its common name derives from its use by Native Americans and settlers as a substitute dye plant for true indigo (Indigofera tinctoria). So far, it has spread very slowly nearby.

Bumble bees and many other native bees are very fond of Baptisia australis.

If I admitted to liking a plant that is on every state and province’s invasive plant list, I would get into trouble. So I’ll just say that since oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare) is on every Muskoka highway margin and dots the old fields in the area, I don’t mind at all if it pops up here too.

It cannot compete with my prairie grasses and perennials in the meadows, but it likes to hang out in spots of unplanted earth and at the edge of the path in front of the cottage, along with weedy buttercups (Ranunculus repens). There’s a childhood memory of oxeye daisies. I remember sitting in the hayfield across the street from my house in Victoria, British Columbia, pulling the white petals from the flowers as I recited “he loves me, he loves me not” – and, of course, being delighted when I sat with a sad, petal-free flower convinced the boy across the street was my Prince Charming. Buttercups were part of my childhood too; we’d hold them under each other’s chin to see if we liked butter. Yes, butter. There were no grownups around to tell us it wasn’t the predictive ability of a flower, but the reflective quality of its shiny yellow petals to create this magic.

Sometimes the oxeye daisies pop up near the lupines.

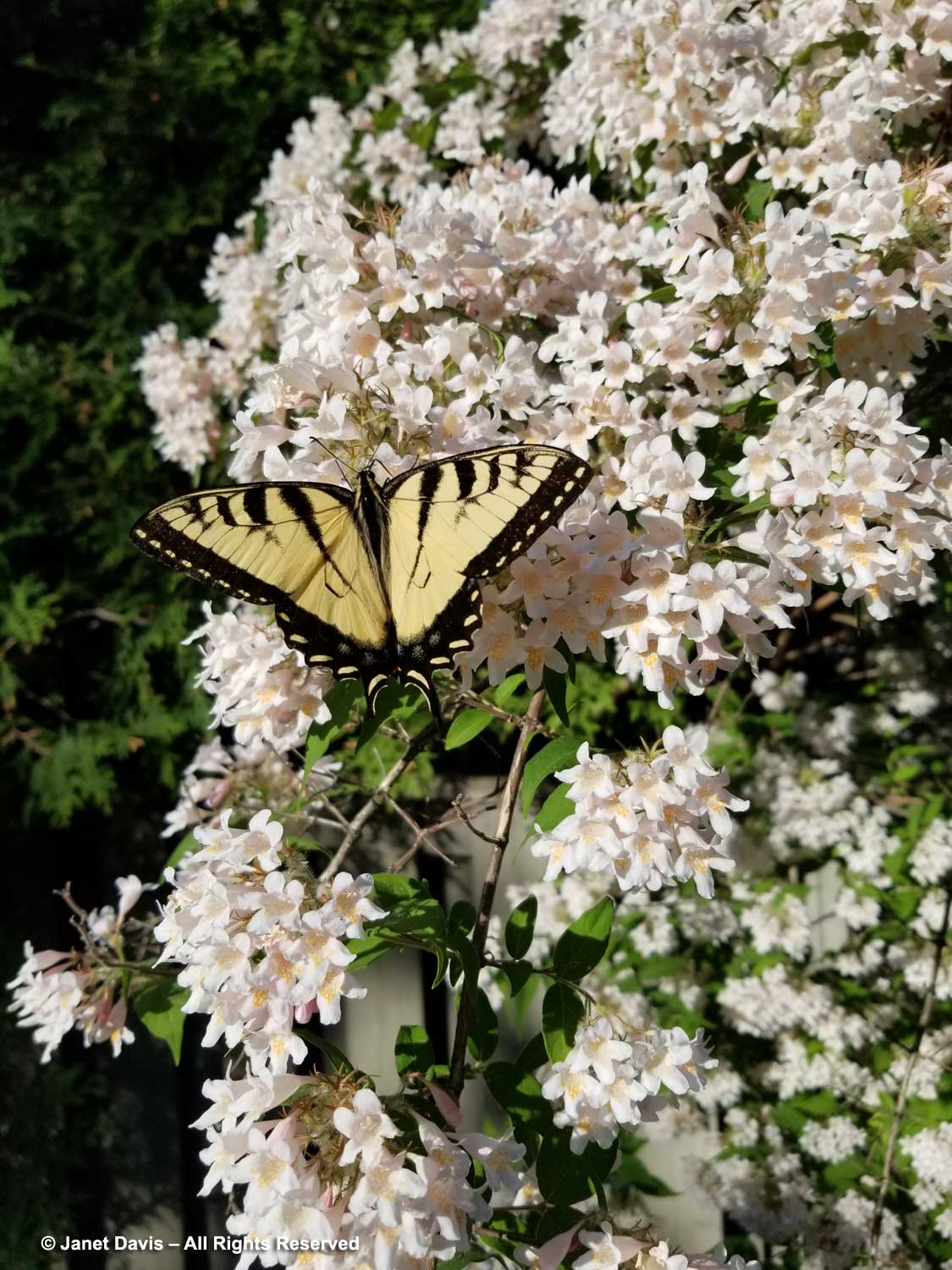

Native hoverflies, short-tongued bees and butterflies often visit the daisies as well.

But path-cutting through the meadows – a necessity in early summer – quickly makes compost of the weedy buttercups and oxeye daisies… until next year.

I grew my golden alexanders (Zizia aurea) from seed and though quite particular about adequate soil moisture and a location out of hot sun, they are self-sowing here and there. A short-lived native perennial from the carrot family, they prefer moist prairies and open woodland and are a host plant for black swallowtail caterpillars.

Though nannyberry (Viburnum lentago) is native to woodland in much of the northeast, I planted it behind the cottage in a spot with moist soil where it is shaded during the hottest part of the day.

Each spring, it bears clusters of white flowers that the bees adore, producing dark-blue summer fruit that the birds eagerly consume. Multi-stemmed, it grows to about 15 feet tall (4.6 m) and 10 feet (3 m) wide with glossy leaves (you can see them on my crown) that turn bright red in autumn.

There is a tiny sprig of pink, lantern-shaped flowers sticking up from the top of my fairy crown; they belong to black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), a native shrub that grows near the lakeshore where its roots are periodically saturated with water from spring floods. Bumble bees nectar in the flowers, and in August….

…… the shrubs yield dark-blue berries that are sweet, though a little seedy.

Finally, my crown bears a few oak leaves with and chewed edges. I made it at the beginning of June 2021, when gypsy moths, aka spongy moths or LDD moths (Lymantria dispar dispar) were beginning to consume the red and white oaks, white pines and many other plants on our hillside…..

….. including my beautiful nannyberry.

It was a devastating and historic predation; by mid-July, the woodlands in our region looked like February, so bare were the deciduous tree branches, below. (You can read last year’s saga with the gypsy moths on my blog here.)

But abundant summer rainfall nurtured the tree roots and they leafed out again with full canopies in August, though the moths laid abundant eggs on our poor trees once again. This year, we’re in a wait-and-see mode, given our cold days this past winter and the chance that a virus might decimate their population. But I sprayed all the egg masses I could reach on the oaks and pines on our acre a week ago, using my homemade cooking-oil-and-soap spray. Fingers crossed.

But let’s not leave on a sad note. Here is my deconstructed #10 crown, with its familiar components: lupine, blue false indigo, oxeye daisy and black huckleberry flowers. And here’s to June!

**********

Here are all my fairy crowns to date:

#1 – Spring Awakening

#2 – Little Blossoms for Easter

#3 – The Perfume of Hyacinths

#4 – Spring Bulb Extravaganza

#5 – A Crabapple Requiem

#6 – Shady Lady

#7 – Columbines & Wild Strawberries on Lake Muskoka

#8 – Lilac, Dogwood & Alliums

#9 – Borrowed Scenery & an Azalea for Mom