Of all the gardens I’ve visited that merit the phrase ‘world-class’, Sissinghurst is near the top, along with neighbouring Great Dixter which I wrote about in my last blog post. It’s not vast in scope, like Philadelphia’s Chanticleer (which I’ve written about a few times), nor does it have the artistic allure of Monet’s garden at Giverny (my spring visit is here), but it has the cult of personality of its founders, the enigmatic author Vita Sackville-West, seen below in a 1918 painting by William Strang, and her diplomat husband Harold Nicolson. In what has been called “an unconventional but harmonious marriage” during which they wrote a combined 70 books, they each had a series of same-sex affairs including Vita with fellow Bloomsbury Group writer Virginia Woolf, who in 1928 wrote Orlando: A Biography, inspired by her lover: a time-travel, gender-bending novel that has been adapted as a film and stage play .

Harold and Vita were also parents of two sons, Nigel and Ben, though Nigel remembered his mother for her frequent abandonments to be with her lovers. In 1973, he would publish ‘Portrait of a Marriage’, incorporating a memoir he found after his mother’s death exploring what she called her “duality” and her relationships with women, along with his own observations of his parents’ loving marriage. But together, Vita and Harold were deeply committed to the garden they designed on the large, run-down property they purchased in 1930. Vita was the romantic plantswoman; Harold was in charge of structure. He created formal rooms hedged in yew; she filled them with old French roses, peonies, irises and spring bulbs. Beyond her novels and books containing her epic poems ‘The Land’ (1926) and ‘The Garden’ (1946), she also penned a weekly column titled In Your Garden in The Observer from 1946 to 1957, later published as a 4-book anthology, below, and still available online.

Sissinghurst was the reason for my early June stay in Kent, courtesy of my London-based son Doug and his partner Tommy. Since we arrived early from our lovely Airbnb in nearby Biddenden and the garden only opens at 11 am, we had lots of time to cool our heels, walking from the parking lot on a path between the timber fence where native red campion (Silene dioica) competed with stinging nettles (Urtica dioica).

We passed the plant shop, where visitors could buy roses….

…. or any number of perennials, below.

We took a moment to gaze across the green fields of Sissinghurst’s 460 acres on the Weald of Kent, of which 5 are intensively gardened and 180 acres are woodland. Here, visitors can walk their dogs, bird-watch and hike to their heart’s content. And thanks to writer Adam Nicolson, Vita and Harold’s grandson (and the husband of British garden maven Sarah Raven), we have a beautifully-written recollection of the farm fields that enlivened Sissinghurst and gave it real purpose when he was a boy – and his own quest to return the working farm to the estate. This is from the excerpted first chapter of his lyrical book Sissinghurst – A Castle’s Unfinished History (2010).

“Remembering what had been here, I came to realize what had gone: the sense that the landscape around the house and garden was itself a rich and living organism. By 2004, all that had been rubbed away. An efficiently driven tourist business, with an exquisite garden at its center, was now set in the frame of a rather toughened and empty landscape. It sometimes seemed as if Sissinghurst had become something like a Titian in a car park.”

We settled into the restaurant until opening time. One of the charms of Sissinghurst Castle Garden, which is run by the National Trust but relies heavily on volunteers, is that there are small touches like the pretty bouquets of flowers from the cutting garden. This one features biennial dame’s rocket (Hesperis matronalis) and foxgloves (Digitalis purpurea) with annual cornflowers (Centaurea cyanus), golden alexanders (Smyrnium perfoliatum) and corn cockle (Agrostemma githago).

This posy featured many of the purples, blues and pinks that Vita adored.

There was a display of blue glass in one of the café windows, presumably part of Vita’s collection of coloured glass.

Attached to the Granary Restaurant are the oasthouse and rondels. Built around 1880, they were still in use to dry and store hops for beer-brewing in 1966, a vital part of the hop-farming industry of Kent which continues to this day. Author George Orwell (1984, Animal Farm) picked hops in the region in the summer of 1931.

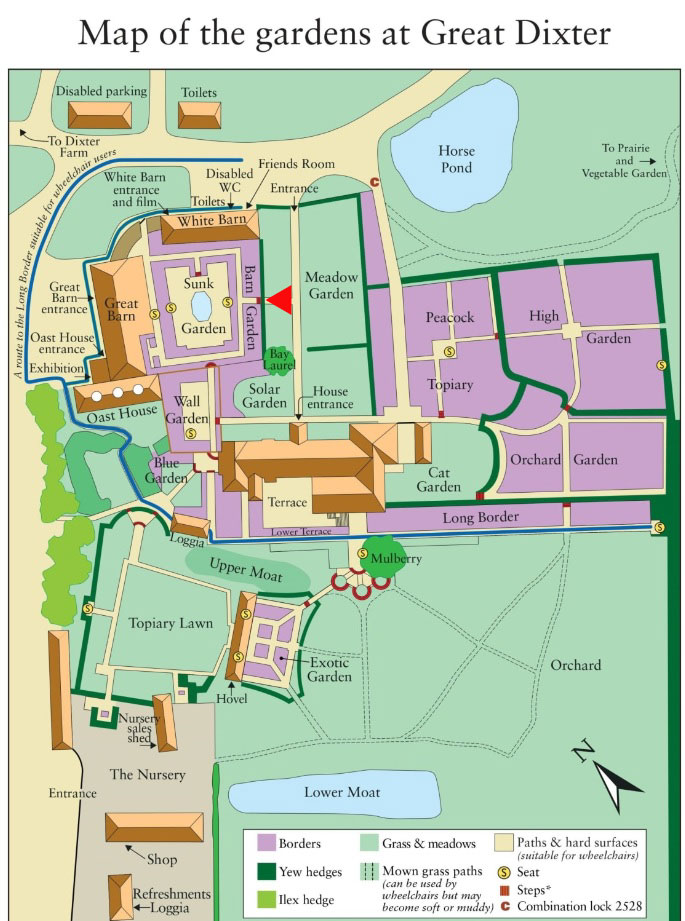

Sissinghurst’s garden rooms are shown on the map below:

I was first in line when the gates opened at 11 am, and as someone who has made “colour in the garden” a focus of my work, I wasted no time heading into one of the gardening world’s best-known meccas, the White Garden. Wrote Vita Sackville-West: “I am trying to make a grey, green, and white garden. This is an experiment which I ardently hope may be successful, though I doubt it … All the same, I cannot help hoping that the great ghostly barn owl will sweep silently across a pale garden, next summer, in the twilight — the pale garden that I am now planting under the first flakes of snow. ”

June is the perfect time to see a White Garden, as I would also discover in the beautiful version designed by Mat Reese at Malverleys later in the week. There are numerous white-flowered perennials, such as the bearded iris (possibly ‘White City’) and peony (likely ‘Festiva Maxima’), below…..

…. and lupines, softened by white-flowered umbellifers such as cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris) and annual Ammi majus.

A statue stood in the shadow of a weeping silver pear tree (Pyrus salicifolia ‘Pendula). Alas, a sunny June day in England and Sissinghurst’s late opening time meant bright contrast for photography, but we garden tourists take what we can get.

Minoan lace flower (Orlaya grandiflora) has become increasingly popular as a self-seeding annual in gardens. White foxgloves and the white-flowered form of red valerian (Centranthus ruber ‘Albus’) add to the display, along with silvery artemisia.

Centaurea montana ‘Amethyst in Snow’ was introduced by my Facebook friend John Grimshaw of the Yorkshire Arboretum in 2000 and is now sold around the world, sometimes as ‘Purple Heart’.

When I was walking out of the White Garden past the Priest’s House to head into the new Delos Garden, I spied this bellflower growing on the wall. It is Dalmatian bellflower (Campanula portenschlagiana); perhaps unsurprisingly, it was once called C. muralis from the Latin ‘of walls’

Delos was a surprise. When we visited Sissinghurst for the first time more than 30 years ago, this part of the garden – originally inspired by a 1935 trip Vita and Harold made to the monument-rich Greek island – was not on view, or certainly unmemorable. In 2018, Sissinghurst head gardener Troy Scott-Smith asked landscape designer Dan Pearson to re-invent the space. Dan wrote a beautiful essay for his newsletter Dig Delve about the process, including a childhood recollection by Adam Nicolson.

An enthusiastic volunteer was on hand in the Delos Garden to help visitors with plant identification.

Wherever I went in England in June – including a visit to Dan Pearson’s garden the following week which I blogged about – I saw giant fennel. In Delos, Dan chose to use Ferula communis subsp. glauca. As he wrote in an essay in Dig Delve, “This is the most elegant of all, in my opinion, for its slender limbs and burnished dark green leaf. I have planted it amongst the rockscape of the re-imagined Delos Garden I recently designed at Sissinghurst.”

Like all giant fennels, it has a bright, yellow inflorescence.

In the garden stand three Greek marble altars originally brought from Delos in the 1820s, as Adam Nicolson recounted in Dig Delve. “There is one element that reaches further back into history than the dreams of the 1930s: three cylindrical Greek marble altars, originally carved in the 3rd or 4th century BC decorated around their waists with swags of grape, pomegranate and myrtle suspended between garlanded bull-heads – boukrania – which now stand at key intervals along the central street of the garden.”

Of their provenance, Adam wrote: “Harold Nicolson’s great-grandfather was Commodore William Gawen Rowan Hamilton, a naval commander in the first years of the nineteenth century, a heroic and romantic figure and passionate Philhellene, who spent the years from 1820 onwards in the eastern Mediterranean, winning the title of ‘Liberator of Greece’ by protecting the Greek rebels against the Turks From time to time during his cruises attacking pirates and fending off the Turk, he would land on an island or a piece of the Turkish-occupied mainland and quietly liberate an antiquity or two, sending them back to his liberal father-in-law in Ireland, Major-General Sir George Cockburn, a flamboyant antiquary who had made a collection of Greek statuary at Shanganagh, his castle outside Dublin.” It was when the Irish castle was sold in 1936 that Harold Nicholson purchased the Delian altars and brought them to Sissinghurst.

As an aside, these days Delos is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, its monuments safe from pirates of all stripes. When I visited in October 2011, below, it made me long to return in spring when the wildflowers were blooming.

Other Mediterranean flowers in the Delos garden include asphodels (Asphodeline lutea)….

…. pinks (Dianthus spp.)……

….. rock roses (Cistus) with happy hoverflies….

….. and the flamboyant red Paeonia perigrina with a visiting bumble bee.

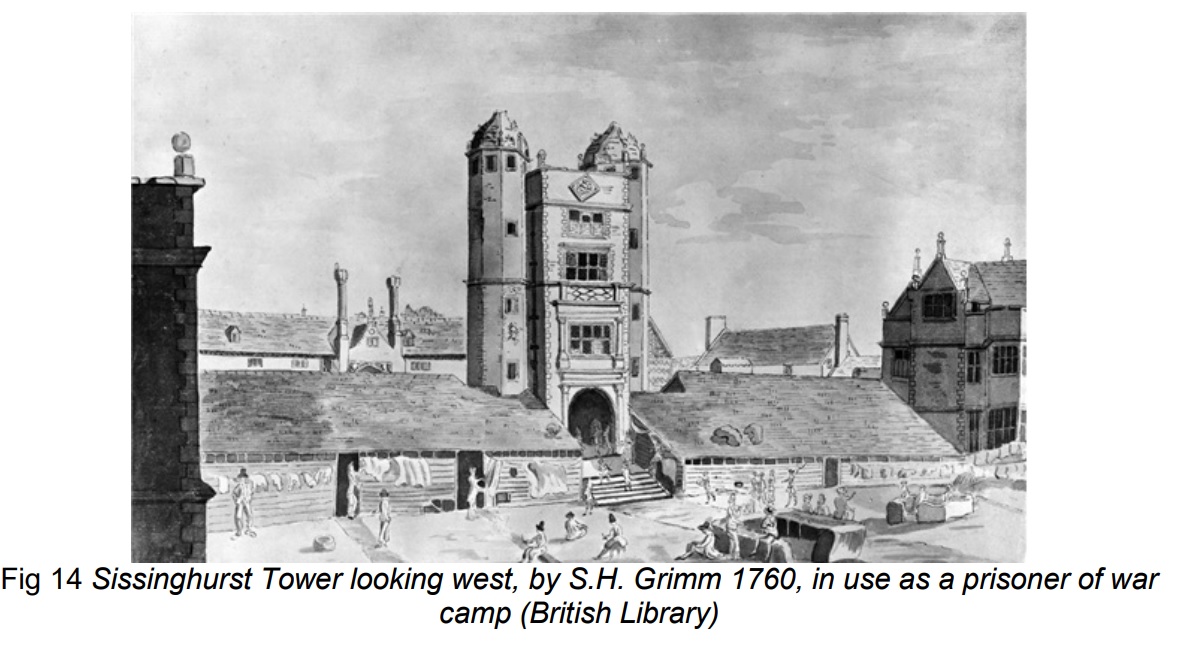

Then it was out of the Delos Garden and off through the 16th century Tudor Tower that once held Vita’s writing room. Sissinghurst was owned by the Baker family from 1490. The first buildings were constructed around 1535 by Sir John Baker, Henry VIII’s Chancellor of the Exchequer. Sir John’s daughter Cicely married Thomas Sackville, 1st Earl of Dorset – thus a connection to Vita Sackville-West four centuries later. The tower, octagonal turret and a large courtyard house were built by Sir John’s son Richard Baker between 1560-1574; Queen Elizabeth I enjoyed a stay here at that time. The Baker family fortunes declined and two centuries later, the house and tower were requisitioned by the state to house 3,000 French prisoners-of-war during the Seven Years War 1756 -1763. There is still graffiti in French from those prisoners on the walls of the tower. Later it became a parish poorhouse and farm, including hop-growing. Around 1800, the main house was demolished by its new owner. When Vita and Harold bought Sissinghurst in 1930, she refurbished the three-storey tower, adding a fireplace to the ground floor room and creating a writing space and library for herself upstairs. It has recently been renovated, complete with her pink walls. During World War II, the tower was used as an observation post since the English Channel was effectively controlled by the Germans whose shelling of the Kent coastline and its towns, according to the BBC, led to the county being called “hellfire corner” and “bomb alley”. (Sissinghurst has a long history nicely encapsulated here by the National Trust who took over the property in 1967, five years after Vita’s death.)

I found this photo in a Heritage Records document for Sissinghurst.

Clambering up the back of the Tower was Lady Banks rose (Rosa banksiae ‘Lutea’) …..

….. with its clusters of pale yellow roses.

The courtyard adjacent to the Tower contains Vita’s Purple Border. When I visited, it was filled with Gladiolus byzantinus subsp. byzantinus, below, also beloved by Christopher Lloyd and Fergus Garrett for the meadows at Great Dixter which I blogged about recently.

I loved the way the purple centres of Allium basalticum ‘Silver Spring’ echoed the colour of the gladioli.

There were so many lovely vignettes here, including the opium poppies (Papaver somniferum) with dame’s rocket (Hesperis matronalis), but time was a-marching.

Then it was into the Rose Garden, with its lush profusion of roses surrounded by early June flowers such as blue Italian alkanet (Anchusa azurea) with magenta foxgloves and euphorbia, below.

It was utterly magnificent – and a little heartbreaking for a photographer hoping for just one cloud to float by above to soften the shadows.

Vita loved her roses. This is ‘Fantin-Latour’, a Centifolia named for the Impressionist painter and introduced into the UK in 1945. Pruning and training of roses is taken very seriously at Sissinghurst. According to Sarah Raven, wife of Vita’s grandson Adam Nicolson, “The big leggy shrubs, which put out great, pliable, triffid arms that are easy to tie down and train, are bent on to hazel hoops arranged around the skirts of the plant. Roses with this lax habit include ‘Constance Spry’, ‘Fantin-Latour’, ‘Zéphirine Drouhin’, ‘Madame Isaac Pereire’…”

Irises play a starring role in the Rose Garden in June. This is the bearded iris ‘Shannopin’, a 1940 American introduction grown by Vita that looked utterly lovely with the alliums just going over.

Siberian iris (Iris sibirica) grow in the mix in the Rose Garden, here with dame’s rocket (Hesperis matronalis) and red campion (Silene dioica).

Annual honeywort (Cerinthe major ‘Purpurascens’) with its sensuous blue bracts is used extensively at Sissinghurst, here with ranunculus.

Yellow lupines make an appearance in the Rose Garden as well. (I’ve read the odd comment that yellow is discordant in this garden, but when you already have a Purple Border filled with purple, mauve, blue and pink flowers, it seems to me that the odd splash of yellow is perfectly fine.)

Moving out of the Rose Garden, I found the Lime Walk: an allée of pleached linden trees (Tilia platyphyllos ‘Rubra’). Unlike the rest of the gardens at Sissinghurst, this was all Harold Nicolson’s creation, not Vita’s – he called it “my life’s work”. It is underplanted with masses of spring bulbs, making overplanting difficult, thus it looked a little bare in early June.

The statue at its terminus is a Bacchante commissioned by the National Trust from sculptor Simon Smith who carved it using Carrara marble from the Cava di Michelangelo and installed it in 2016. On his page, the artist says: “The sculpture depicts a dancing girl, slightly drunk, who has suddenly noticed something in the distance”. What could it be?

If he were a little closer, she might have noticed the young man below, standing in a shade-dappled carpet of ferns in The Nuttery. In the spring of 1930, when Harold and Vita were considering whether to buy Sissinghurst with its ruined buildings, Harold wrote: ‘We come suddenly upon a nut walk and that settles it…’ The garden features 56 coppiced hazels (Corylus avellana) and a variety of woodland plants.

The Moat Walk features Wisteria floribunda ‘Alba’ espaliered on a brick wall facing an azalea bank across the lawn.

After the cool green of the Lime Walk and Nuttery, the South Cottage Garden — my final stop — was a burst of June sunshine with its warm palette of yellow, chartreuse, orange and red. I would have stayed here a long time if we hadn’t had to find lunch before visiting Great Dixter in the afternoon.

You can see a little of the South Cottage behind the geums and irises….

…. and the wallflowers. When Vita and Harold bought Sissinghurst in 1930, the cottage was a fragment of the ruins of the original 1570 house. They restored and extended it that decade and it became the intimate place where each had a bedroom and Harold had his office overlooking the garden.

The colours here seem to glow, including the lacy yellow fumitory (Corydalis lutea), hakonechloa grass and golden iris….

…. and the night-scented flowers of the unusual evening primrose Oenothera stricta ‘Sulphurea’.

Corn poppies (Papaver rhoeas) were sprinkled about….

…. and it was a thrill, in my final moments at Sissinghurst, to glimpse the last of all tulips to flower, the tall, blazing-red Tulipa sprengeri. What a joy this sunny June garden was, as were the pale flowers in the White Garden and the abundance of the Rose Garden.

I will leave the last words to Vita Sackville-West, from her poem The Garden (1945)

Sweet June. Is she of Summer or of Spring,

Of adolescence or of middle-age?

A girl first marvelling at touch of lovers

Or else a woman growing ripely sage?

Between the two she delicately hovers,

Neither too rakish nor, as yet, mature.

She’s not a matron yet, not fully sure;

Neither too sober nor elaborate;

Not come to her fat state.

She has the leap of youth, she has the wild

Surprising outburst of an earnest child.

Sweet June, dear month, while yet delay

Wistful reminders of a dearer May;

June, poised between, and not yet satiate.