Two of the major reasons I wanted to participate in this year’s Garden Fling in Washington State’s Puget Sound region – to leave behind the July meadows at my cottage on Ontario’s Lake Muskoka when the wild beebalm is coming into bloom – were, quite simply, Heronswood and Windcliff. All of the gardens we visited held their share of magic and heaps of horticultural expertise, but the chance to visit these two related Kitsap Peninsula garden meccas made the decision for me.

In 2000, when Dan and Robert were still at Heronswood, they found this property on a small lane in the village of Indianola, as Dan said in a speech at the New York Botanical Garden some years ago. It was 6-1/2 acres on a 200-foot bluff above Puget Sound and “the complete opposite of what I was gardening with at Heronswood.” Windcliff had been given its name by its then-owners, Peg and Mary, who had been raising German shepherds here while regularly mowing acres of summer-browned lawn. As Dan says, this part of the Pacific Northwest averages just 28 inches of rain per year with little measurable rain between spring and fall. So for him, a lawn was out of the question. “I’m not a friend of this whole concept of throwing water and fertilizer on something to make it grow, so we can then cut it on a weekly basis. What an amazing waste of energy.”

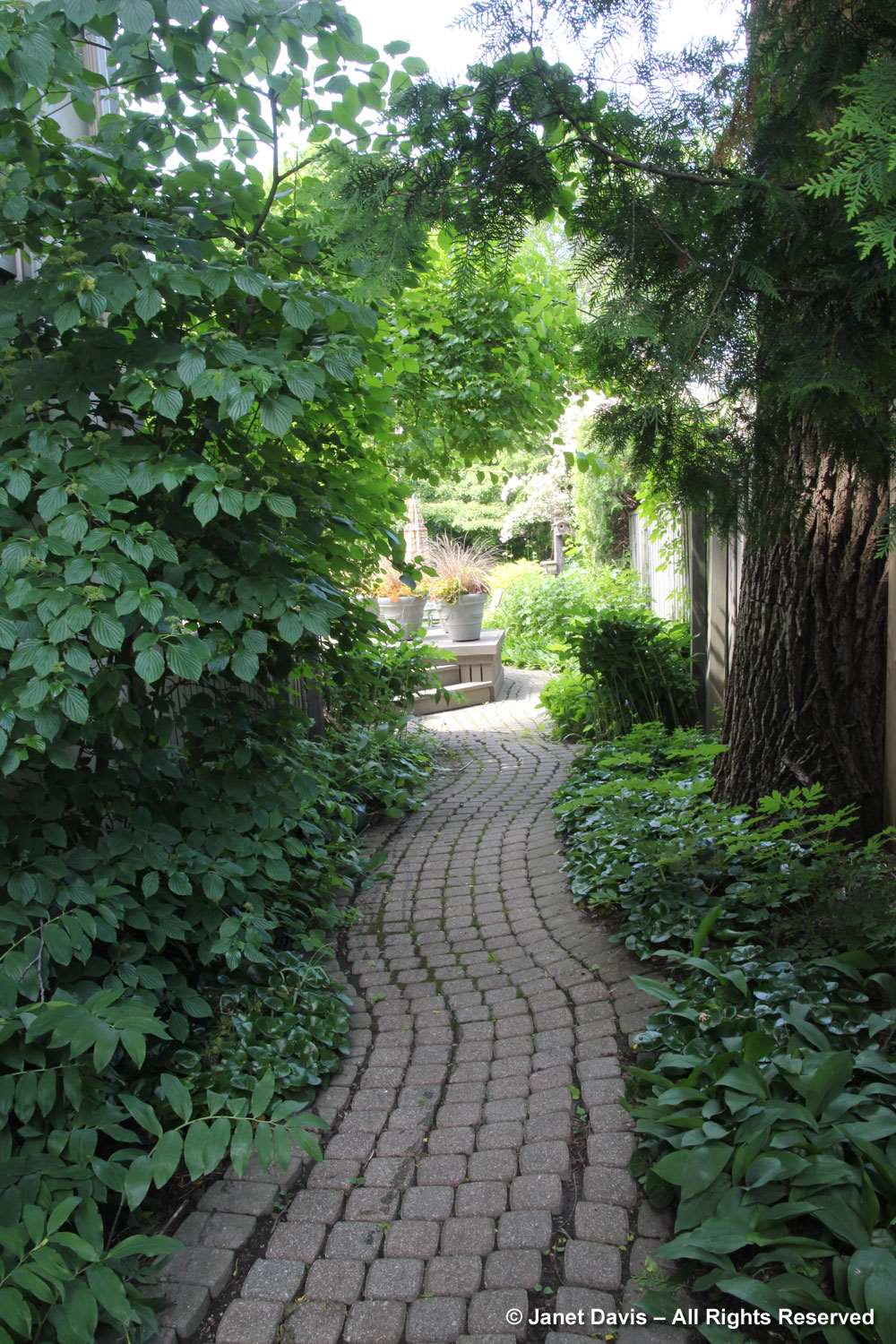

I wrote about Heronswood in my last blog – now let’s head down the long driveway toward the house at Windcliff.

There are 4 acres of treasures on this side of the house under the big forest trees, including an arboretum of rare trees and shrubs with a rich ground layer of unusual plants, many also sold in the on-site nursery. Be sure to check out the colourful bamboos, including Fargesia robusta ‘Campbell’, an eye-catching clumping species with its white sheaths.

There are bamboo tunnels, too.

At Heronswood, I saw a single plant of Alstroemeria isabellana; here it grows in a generous drift.

Nearby is Alstroemeria ‘Indian Summer’, a hardy, clumping form of Peruvian lily with purplish foliage that tops out at 3-feet (1 m) in height.

Flame nasturtium (Tropaeolum speciosum) clambers through shrubs and trees, already forming its beautiful, dangling fruit.

I snap photos as I walk and recognize this small, elegant tree as a podocarp. But its identity is confirmed when I find John Grimshaw’s erudite page on Podocarpus salignus, including his photo of this very tree at Windcliff.

Japanese clethra (C. barbinervis) is showing off its scented, spiky, white flowers above a trunk with handsome, exfoliating bark.

At the bottom of the driveway we arrive at the house: a low-slung, Asian-inspired building in three connected pavilions designed and built by Robert and clad in aubergine-purple shakes. (Even the chimney stones are colour-coordinated!) Stretching across the front is an architectural assemblage of fibre-clay pots. Wreathed around the front door is a perfumed, narrow-leafed sausage vine (Holboellia angustifolia) grown from seed Dan collected on one of his twenty exploring trips to the north part of Vietnam. That particular collection took the form of Dan’s guide eating the sweet fruit, then spitting the dark seeds into a zip-lock bag. Like all seeds he collects, permits must be issued by the host country, then the seeds are sent for inspection directly to the USDA office in Seattle which is now very familiar with his work.

“We wanted to plant woodland treasures outside the front door at ground level,” said Dan, “but it was impossible with our dogs, all those things I wanted to baby along. So we decided to do a pot wall to lift all those treasures off the ground. Robert took this project on. We found some inexpensive fibre pots, knocked the bottoms out, stained them, then erected about a 25-foot-wide wall.” A cluster of brown toothed lancewood trees (Pseudopanax ferox) from New Zealand grow here in their Dr. Seuss juvenile form.

I love the way this cubist container garden fits together, unifying the habitat for the plant treasures.

Dan meets us in the front, giving us an overall description of Windcliff and relating how the January 2024 freeze devastated parts of the garden, causing the loss of countless plants and necessitating the current replanting of certain areas.

Moving west around the house I pass a bamboo-fenced, shady alcove garden with windows into the dining room and beyond that, windows facing south to Puget Sound. As Dan has acknowledged, it was a rare opportunity to design both a garden and house at the same time. The light fixture visible through the window was inspired by the long tentacles of the giant Pacific octopus, the largest octopus species on the planet with a 20-foot arm-span, a creature that lives in the waters just off the bluff. To see a photo of the fixture from the inside, have a peek at Andrew Ritchie’s review of Dan’s book ‘Windcliff’.

This area features a stand of hardy shade ginger (Cautleya spicata), a Himalayan native. Several cultivars have been introduced, including a selection called ‘Arun Flame’, which Dan and Bleddyn and Sue Wynn-Jones of Crug Farms in Wales discovered in eastern Nepal on a collecting trip with the American novelist Jamaica Kincaid. She wrote a 2005 memoir called “Among Flowers: A Walk in the Himalaya” of that taxing expedition.

A small gravel garden partly enclosed by bedrock sits outside the passage to the master bedroom at right.

I turn the corner of the house and walk along flagstones towards the bluff gardens on the south side. It’s a challenge to identify plants at Windcliff but I might venture a guess that the variegated shrub above my head is Stachyurus praecox ‘Oriental Sun’.

I’m moving so quickly that I capture the delicate shadow play near my feet but neglect to look up to see what is making these patterns – likely Schefflera taiwaniana. Schefflera is one of Dan’s favourite genera – growing up in northern Michigan, he had a schefflera as a houseplant – and this species is one of the hardiest for a shady spot. (You can hear him talk about it in this Fine Gardening video.)

Coming into the sunshine, I glimpse the bluff and the water beyond through the upswept, coppery limbs of an iconic plant for gardeners in the west, a handsome manzanita (Arctostaphylos). That pretty table was created some 25 years ago for Dan by Bainbridge Island artists George Little and David Lewis.

Nearby is a bog garden with different pitcher plant species (Sarracenia spp.)

Note that lovely Yucca rostrata behind the kniphofia in the background.

A drift of Ammi visnaga near the house reminds me of the Conservatory Garden at New York’s Central Park, where I last photographed this species. It was originally designed by Lynden Miller, one of Dan’s horticultural heroes. (This is my 2016 blog on that amazing garden.)

Standing now on the ‘bluff side’, I look back at the house through a planting of red-flowered Mexican bush lobelia (Lobelia laxiflora). I think the big, lush leaves are from Eucomis pallidiflora subsp. pole-evansii, a very tall pineapple lily species which seeds around this garden.

Dan is nearby so I tell him the story of asking to photograph him at Heronswood back in September 2005, when all he really wanted to do was get to his waiting birthday cake. He graces me with a big smile, but I’m also distracted by….

…. the giant hog fennel (Peucedanum verticillare) behind him!

As a lover of colour in the garden, I’m drawn towards the lower bluff where brilliant red and scarlet crocosmias are partnered with agapanthus and rich blue Salvia patens. If you squint, you can see the skyscrapers of Seattle in the distance. And on a clear day, the view of Mount Rainier is spectacular.

The vignette is enhanced by the eucomis foliage, which will mature to yield a pineapple lily that reaches 5-6 feet in height. When the previous owners were here, they had an expansive view of Puget Sound over their summer-brown lawn. In planning his own garden, Dan wanted the view not to be an open book dominated by sky and water, but to be glimpsed through an interesting array of plants of various sizes, habits, colours and textures.

As I stand quietly in this area, a female rufous hummingbird becomes brave enough to forage in the crocosmia flowers.

See how her head feathers are brushed with the golden pollen on the anthers, which she’ll carry with her as she flits from plant to plant, ensuring that seed forms in the beautiful fruits of crocosmia?

I see splashes of orange behind the agapanthus in this section, the spikes of red-hot poker (Kniphofia) and drifts of California poppy (Eschscholzia californica).

The sweet perfume of Spanish broom (Spartium junceum) is in the air here. It’s a little dèja vu moment for me because when we were in Tuscany visiting our youngest son and daughter-in-law in late May, this Mediterranean shrub, which they call “ginestre”, was in bloom throughout the hills. In fact there was a festival of flowers in Lucignano, the village where we stayed, called “Maggiolata” which uses the yellow blossoms of the shrub as its floral motif. At the edge of the bluff on the right, you can see the native madrona tree (Arbutus menziesii) whose shimmering, copper-bronze trunk and branches inspired the colour scheme of the house and its furnishings.

Close to the bluff edge is a circular stone fire pit called the council ring. Created by Portland mosaic artist Jeffrey Bale, it features an inset stone face by sculptor Marcia Donohue.

Walking back towards the house, I see purple Jerusalem sage (Phlomis purpurea), one of many Phlomis species here. (If I am wrong, I hope to be corrected in comments.)

Then a few plants I like to call “scrim plants”. Dan has said: “I was a dinosaur when it came to the use of grasses. I was the last person in North America to appreciate grasses, but Heronswood was not a grass sort of garden. That diaphanous quality and the movement they provide to the garden is so incredibly important.” Here he uses giant feather grass (Stipa gigantea/Celtica), one of the very best grasses to use as a screen through which to glimpse other plants, like the agapanthus.

Angel’s fishing rod (Dierama pulcherrimum) creates the same screen effect in front of white-flowered Olearia cheesmanii, a New Zealand bush daisy.

A lovely, single, orange dahlia pops up throughout the bluff garden.

There are a few gravel-mulched terraces leading up to the house level here. (And can I just say I LOVE airy bamboo fences…)

This one features Salvia ‘Amistad’ with a small kniphofia.

Steps up to the house are flanked by Yucca gloriosa with soft silver sage (Salvia argentea) and a white-flowered salvia (likely S. greggii) at the base.

The terraces include a large pond and waterfall. The pond once held a collection of koi, but the local river otter put an end to the fish.

Large stepping-stones cross the pond beside a waterlily.

On the other side of the steps, the pond continues below a deck with a little viewing overlook to gaze out on the garden.

One of the family dogs (Babu?) meets me near the deck but refuses to pose. He says he’s tired of paparazzi. Fine.

A line of clay-fibre planters sits facing south, all the better for the succulents, cacti and other sun-lovers planted in them.

When I reach the deck, Dan is there, gazing out at his garden. Beyond is a grove of Dustin Gimbel’s ‘Phlomis’ ceramic sculptures.

2024 started as a difficult year for gardeners in the Pacific Northwest, who lived through several consecutive January nights of deep-freeze temperatures – as low as 15F (-10C) on Jan. 12-13 in the Seattle area. That’s when many of those tender Mediterranean and South African plants curl up their toes and die. At Windcliff, much of the shrub framework was lost, including many plants that had never been affected by cold before. When he returned home from warmer climes in February, Dan called the garden a “mass murder crime scene investigation” and laid the blame on the Fraser Valley in British Columbia. (As a Canadian, I accept the blame on behalf of the Polar Vortex, even though I think Alaska might have had a hand in the dirty work too.) In late winter, he sowed a buckwheat cover crop to smother weeds and improve the soil’s tilth, then in late April he covered the entire space, 10,000 square feet, with a 10-mil sheet of white plastic to ‘solarize’ the seeds of weedy mulleins and exotic grasses. In late September when the autumn rains begin, he’ll plant bulbs along with native plants and grasses in a “low-mow meadow”. As he said on his Facebook page with an indefatigable air of optimism: “I could not bring myself to paint between the lines of those few things that survived, so nearly 25 years later, we begin again. What an adventure!!”

Parts of the bluff-side garden have been newly planted and mulched in gravel.

I love this Chilean annual, Nolana reichei, aka “flower of seven colors”. (I counted, it’s true.)

Our stay is coming to an end but I haven’t yet seen the vegetable garden or nursery, so I head off up the east side of the house towards the greenhouse. Fragrant lilies grow here, along with phlomis.

Robert Jones is manning the sales booth and my fellow travellers are in seventh heaven selecting rare plants….

…. of all kinds. Fortunately, our bus has capacious storage space below. (Windcliff does not do mail order, but plants are available for purchase on open days, and Monrovia has a Dan Hinkley Plant Collection too.)

As a Canadian, I’m not permitted to bring plants across the border without a phytosanitary certificate, so I content myself with window shopping.

Then I head to the agapanthus beds where I see some familiar names on the plant labels, like Portland gardener Nancy Goldman….

…. and my dear Seattle friend, Sue Nevler. Said Dan of a happy day now a decade ago: “Robert and I had at last the opportunity to become married and we had a lovely party of friends coming in from all parts of the country and Europe, and we gave all the women a label and they got to go out and celebrate their favourite agapanthus seedling, and then we’ve named it for them. So there will be a lot of feminine-sounding agapanthus being introduced into cultivation in the near future.”

The perfume of sweet peas is in the air here, and I’m charmed that this sophisticated garden has devoted so much space to growing this old-fashioned annual.

Who can resist burying their nose in fragrant sweet peas?

Nearby is the vegetable garden. Said Dan in his talk at New York Botanical Garden: “It was vegetable gardening that brought me into this whole world I feel so privileged to be a part of. As a young kid, I had the family vegetable garden responsibilities and it is still now the place you’re going to find me most often, in the potager that we put in at Windcliff….something we eat from every single day of the year. That is our reason for the garden, when it comes right down to it – this opportunity to have fresh vegetables that we know precisely where they came from, how they were treated, how they were loved.”

A clay pot is overflowing with spinach.

The greenhouse offers extra heat for tomatoes, which grow side-by-side with sarracenias.

While apples ripen on a tree nearby.

It’s time for us to head to Dan & Robert’s next-door neighbours, the Brindleys, for a group portrait, an annual event at the Fling. I have just enough time as I bid farewell to snap a photo of a Mark Bulwinkle rusty iron screen.

I thought it was appropriate to include this photo in the lovely Brindley garden overlooking Puget Sound, courtesy of Becca Mathias. I am slouched in the front row, second from left. If I look happy as a clam, it’s because I’ve just spent a few hours in what passes in gardening for heaven. Thanks, Dan and Robert!

***********

Are you tired of looking at garden photos yet? No? Well, I have been fortunate to visit and blog about a few other personal gardens designed by eminent plantsmen, including: