In 1768, when the young lawyer Thomas Jefferson began building his home atop the “little mountain” (literally monticello, in Italian) that he had inherited from his father, there were no gardens. The land was rich red soil – known as “Davidson Clay” – overlooking Virginia’s Piedmont and the Blue Ridge Mountains – a tobacco plantation, part of 5000 acres he had inherited from his father. In time, however, Jefferson would establish gardens here where he could experiment with all manner of plants, both edible and ornamental, and the meticulous garden records that he would make contribute to our current understanding of American “heritage plants”.

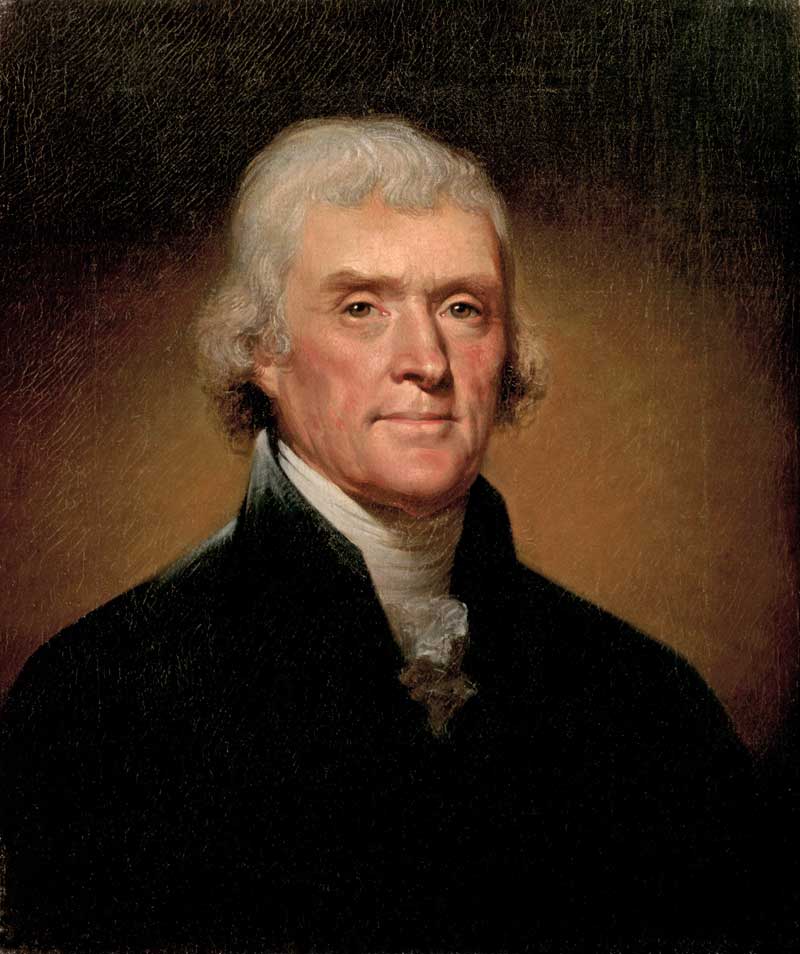

Born in 1743 in Shadwell VA, just down the road (now the expressway) from Charlottesville, Virginia, Thomas Jefferson was one of six children born to the cartographer Peter Jefferson, who mapped the route through the Appalachian Valley that would become the ‘Great Waggon Road’ connecting Philadelphia to the colonies of the American South. Home tutored at first, he then attended school where he learned several languages. He attended William & Mary University in Williamsburg, VA in 1760, studying philosophy for two years. While there, he was greatly influenced by one teacher. “It was my great good fortune, and what probably fixed the destinies of my life that Dr. William Small of Scotland was then professor of mathematics, a man profound in most of the useful branches of science, with a happy talent of communication, correct & gentlemanly manners, and an enlarged & liberal mind. He, most happily for me, became soon attached to me & made me his daily companion when not engaged in school; and from his conversation I got my first views of the expansion of science & of the system of things in which we are placed.” He then read law for five years, and was was called to the Virginia bar in 1767; he practised circuit law for five years.

In 1772 he married his 3rd cousin Martha Wayles Skelton, a widow, and brought her to his new home at Monticello, where they spent 10 years together and had 6 children, only two of whom survived childhood. When her father John Wayles died in 1773, Martha Jefferson inherited his slaves, among them a woman named Betty Hemings and her six children, all of whom were half-siblings of Martha’s, since they were fathered by her own father. Betty’s youngest child was Sally Hemings. (More on Sally later.)

In 1775, Thomas Jefferson was a Virginia delegate to the second Continental Congrass, and distinguished himself by publishing his paper A Summary View of the Rights of British North America. The achievement for which he is most renowned, of course, is the Declaration of Independence, America’s founding document. In the 1818 painting by John Trumbull, below, 33-year old Thomas Jefferson – at 6-feet 2-½ inches – is depicted as the tallest of the “Committee of Five”, i.e. the five men in the drafting committee, seen standing below as they present their draft to Congress on July 4, 1776. From left, they are John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston, Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin.

In 1779-81, Thomas Jefferson was Governor of Virginia. In 1782, four months after the birth of their sixth child, Martha Jefferson died. Jefferson was devastated and spent weeks isolated from his family. As his eldest daughter recalled later: “When at last he left his room he rode out and from that time he was incessantly on horseback rambling about the mountain in the least frequented roads and just as often through the woods; in those melancholy rambles I was his constant companion, a solitary witness to many violent bursts of grief.” Jefferson had promised Martha that he would never remarry.

From 1784 to 1789, Jefferson served as U.S. Minister to France under President John Adams. It was during this appointment that he developed a deep love of art and music and toured many English pleasure gardens, nurturing a taste for landscape designs based on the picturesque style of 18th century landscape painters and also the ornamental farm (ferme ornée). It was while he was in Paris that he began an intimate relationship with the teenaged slave Sally Hemings, (his late wife’s half-sister) who accompanied Jefferson’s 9-year old daughter Polly to France when her sister died of whooping cough.

Thomas Jefferson became the third president of the United States after George Washington and John Adams, serving two terms between 1801 and 1809. At the time, the journey by carriage from Monticello to the White House took 4 days and 3 nights. (We make this journey by car in 2-1/2 hours). Jefferson’s most significant achievement occurred during his first term when he negotiated the Louisiana Purchase with France, acquiring a vast swathe of the middle of North America (827,000 square miles) from the French, for a total of $15M (US). In 1803, he commissioned the Lewis & Clark expedition (1804-06) to the American west, a journey that became the source of many Indian artifacts originally displayed in the house, but later lost. It also provided the president with new Western native plants to be grown at Monticello, such as narrow-leaved coneflower (Echinacea angustifolia), below.

Visiting Monticello, a United Nations World Heritage Site, in June 2017, we begin our tour in the house. Close to its end, a sudden thunderstorm means we must take shelter in the basement, along with several other tour groups. Here we find ourselves huddled outside Thomas Jefferson’s wine cellar. When we are finally able to leave the shelter of the house, we head out under the dripping willow oaks (Quercus phellos) and begin our tour of the flower garden.

But it is not possible to talk about the gardens at Monticello without prefacing my tour with a look at how this Virginia plantation functioned under Thomas Jefferson.

SLAVERY

That slavery runs through the story of Thomas Jefferson and Monticello is part of the paradox of this man, who began his law practice defending seven slaves and later attempted to use his co-authorship of American’s founding document to legislate against the practice. According to the Library of Congress: “Thomas Jefferson first tried to condemn slavery in America with the Declaration of Independence. Although his original draft of the Declaration contained a condemnation of slavery, the southern states were adamantly opposed to the idea, and the clause was dropped from the final document. In 1784, he again tried to limit slavery, suggesting in a report on America’s new western territory that “after the year 1800 of the Christian era, there shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in any of the said States..’ Again, due largely to the resistance of the southern states, the proposal was rejected. In frustration, the Virginian later commented: “South Carolina, Maryland and Virginia voted against it…The voice of a single individual of the State which was divided, or of one of those which were of the negative, would have prevented this abominable crime from spreading itself over the new country…[I]t is to be hoped…that the friends to the rights of human nature will in the end prevail.’ “

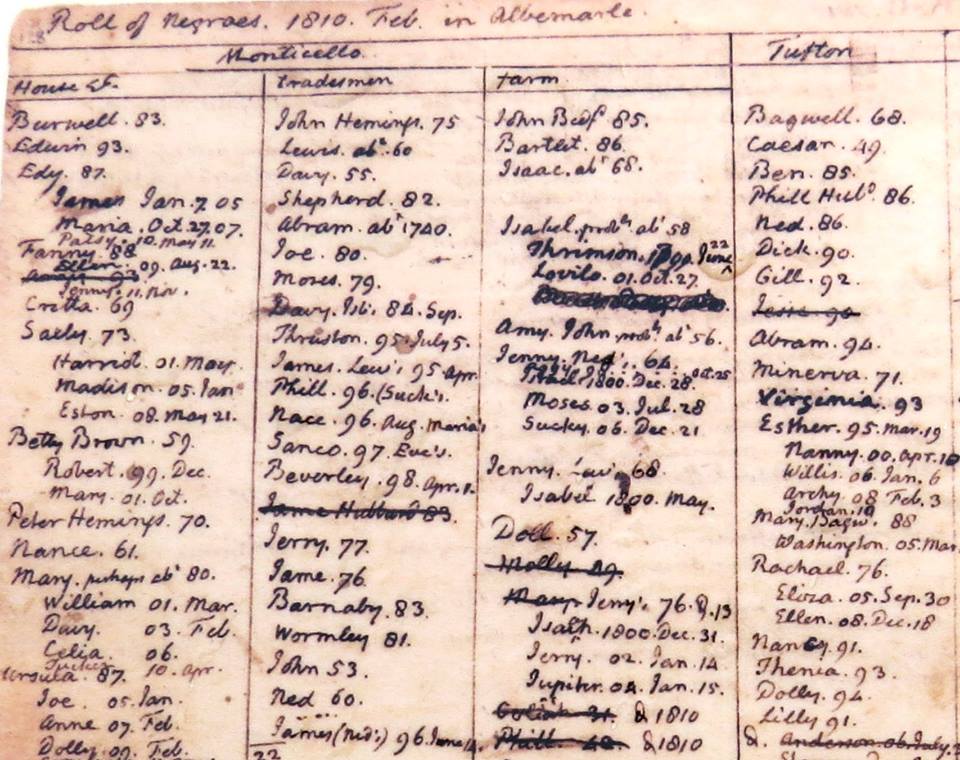

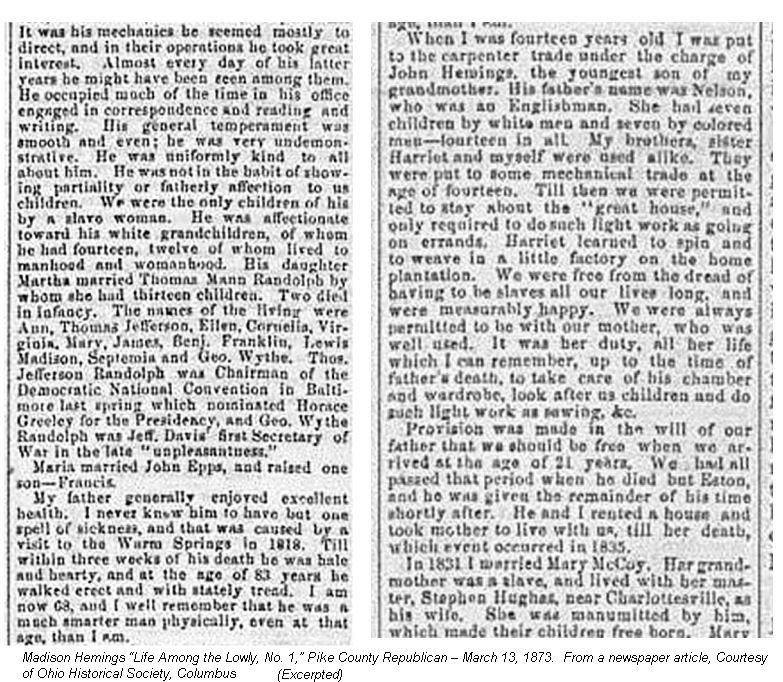

It was Madison Hemings, listed by Thomas Jefferson as Sally Hemings’s 5-year old in the 1810 Slave Roll below, (middle, first column) who helped uncover the true story of Jefferson’s relationship with his mother, something that had been whispered loudly by the president’s political enemies, but denied by the Jefferson family for more than a century.

In 1873, in a series entitled “Life Among the Lowly” in the Pike County Republican, (parts of which are shown below), Madison Hemings, by then a freed slave living in Ross County in the free state of Ohio, wrote that his mother Sally, who was the half-sister of Jefferson’s wife, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson and a household slave of Thomas Jefferson, gave birth to five* children by him. Their relationship began in Paris, when Sally travelled there with Polly, Jefferson’s youngest daughter, after her sister died of whooping cough. Madison Hemings’s memoir was part of a PBS documentary. “But during that time my mother became Mr. Jefferson’s concubine, and when he was called back home she was enceinte by him. He desired to bring my mother back to Virginia with him but she demurred. She was just beginning to understand the French language well, and in France she was free, while if she returned to Virginia she would be re-enslaved. So she refused to return with him. To induce her to do so he promised her extraordinary privileges, and made a solemn pledge that her children should be freed at the age of twenty-one years. In consequence of his promise, on which she implicitly relied, she returned with him to Virginia. Soon after their arrival, she gave birth to a child, of whom Thomas Jefferson was the father. It lived but a short time. She gave birth to four others, and Jefferson was the father of all of them. Their names were Beverly, Harriet, Madison (myself), and Eston–three sons and one daughter. We all became free agreeably to the treaty entered into by our parents before we were born. We all married and have raised families”. Madison said he had been named by Dolly Madison, who was visiting Monticello with her husband and Thomas Jefferson’s good friend, President James Madison, at the time the baby was born. It would take a 1998 DNA test to prove that what Madison Hemings had written was accurate: he and siblings were Thomas Jefferson’s children. In 2000, following their own scholarly investigation, the Monticello/ Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, Inc, issued this statement: “The best evidence available suggests the strong likelihood that Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings had a relationship over time that led to the birth of one, and perhaps all, of the known children of Sally Hemings.” (*most sources say 6 children, but their first child died soon after birth)

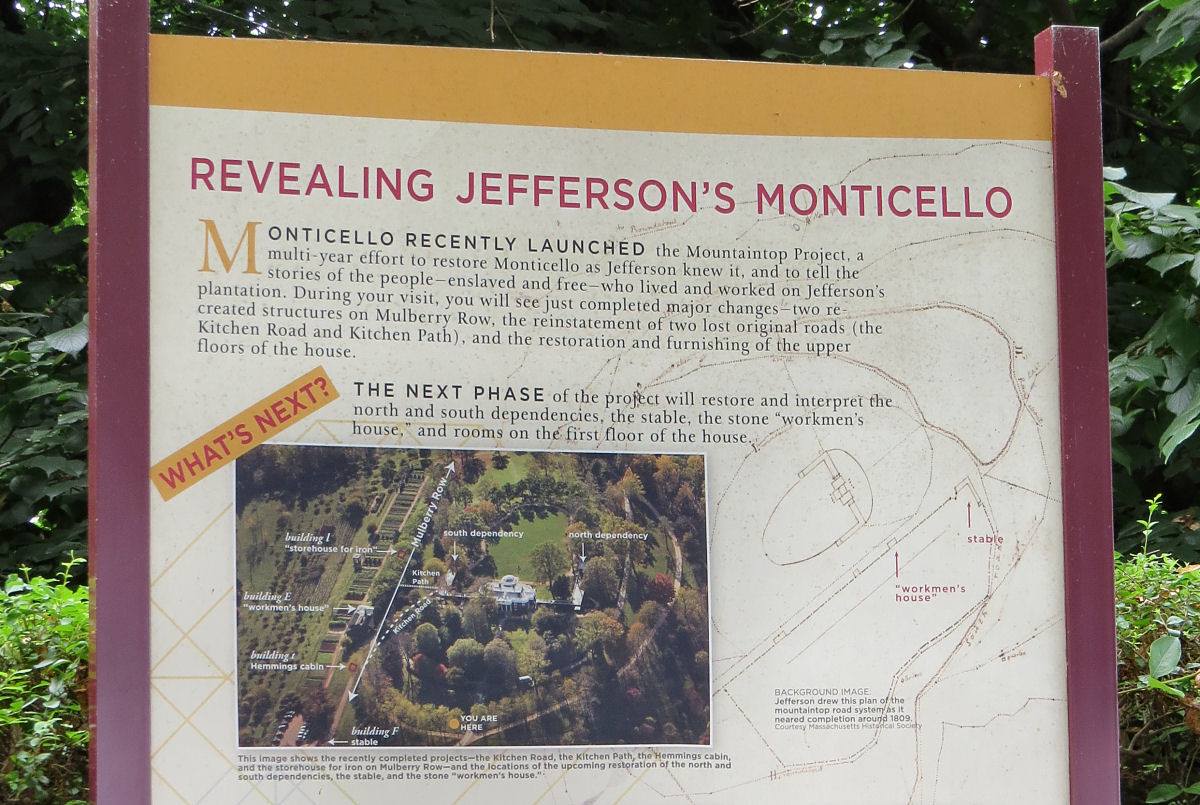

You can read about Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson in this Washington Post article, which describes Monticello’s recent efforts to situate the reality of Monticello’s enslaved people within the heroic history of Thomas Jefferson. It’s part of The Mountaintop Project, the current thrust at Monticello to tell the stories of its people, including the slaves, as described in the interpretive sign below.

Yet while they have included the “Hemings Family tour” in their ticket lineup, Monticello still seems reluctant to clearly state the nature of the Hemings-Jefferson relationship in the description.

And I loved this touching NPR story, featuring modern-day descendants of Thomas Jefferson’s slave children, concerning the formation of Monticello Community for “all the descendants of workmen, artisans and slave, free, family, whatever, at Monticello”.

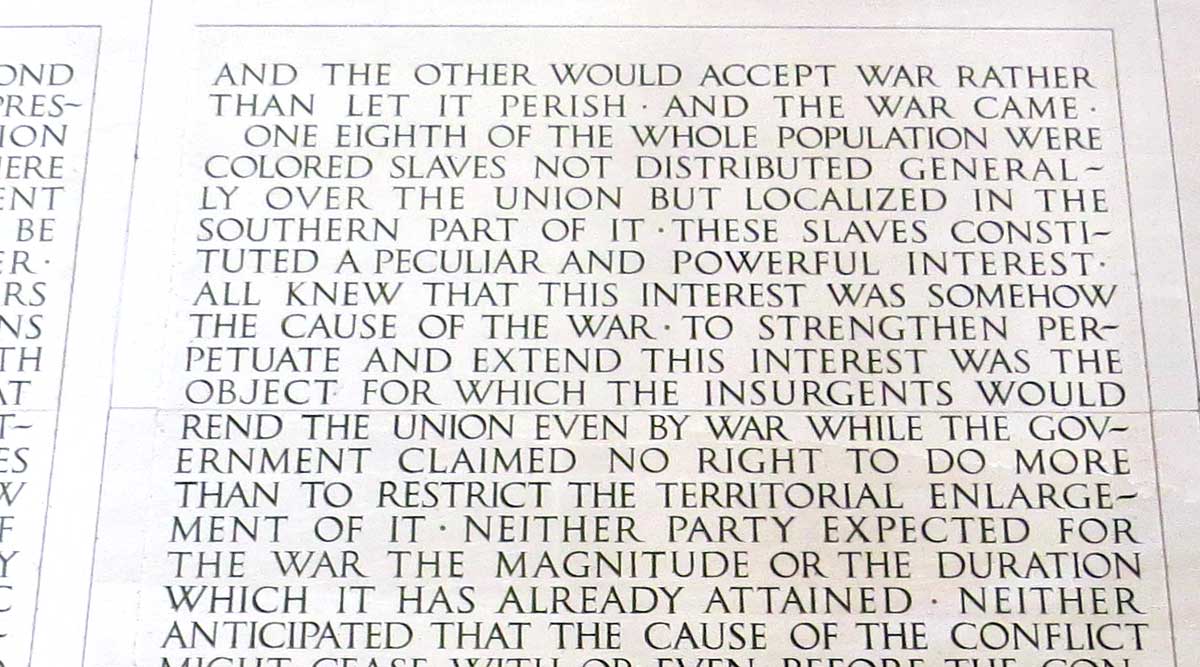

Though we like to view history through the prism of our enlightened moral standards, (and there was spirited defence of Jefferson by scholars before the DNA test results were announced), it is worth noting that 12 of the first 18 presidents owned slaves, including George Washington. It would be the 16th president, Abraham Lincoln, who would finally succeed in ending slavery through the 13th Amendment, though it would take a bloody civil war and 620,000 deaths to accomplish that end. These are the words we saw just two days before visiting Monticello, on the walls of the Lincoln Memorial on Washington’s National Mall. They form part of Lincoln’s second Inaugural Address in 1865:

So, acknowledging that today’s Monticello owes its place in history thanks as much to the labour of its enslaved residents as to the creative scientific genius of Thomas Jefferson, let’s begin our tour just outside the main house in the flower garden.

THE FLOWER GARDEN

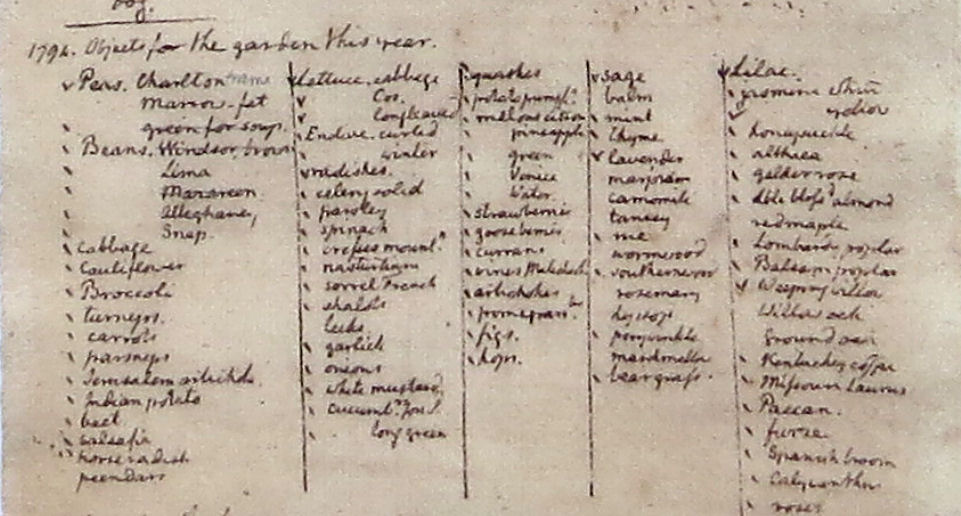

Jefferson maintained meticulous records of all his biological observations. He kept a Weather Memorandum Book, in which he recorded precipitation, wind, temperature. And he noted details of his garden purchases and plans in his garden diary, printed as Thomas Jefferson’s Garden Book in 1944. Below is his page from 1794, a century-and-a-half earlier; showing his painstaking attention to detail (presumably his shopping list for the season): peas, beans, spinach, curly endive, Jerusalem artichoke, ‘garlick’, white mustard, ‘camomile’, lavender, wormwood, mint, thyme, balm, rosemary, marsh mallow, strawberries, gooseberries, figs, hops, lilac, red maple, Kentucky coffee tree, Lombardy poplar, weeping willow, willow oak, among many others. As the authors say in Thomas Jefferson’s Flower Garden at Monticello (1986, 3rd edition), “No early American gardens were as well documented as those at Monticello, which became an experimental station, a botanic garden of new and unusual plants from around the world.”

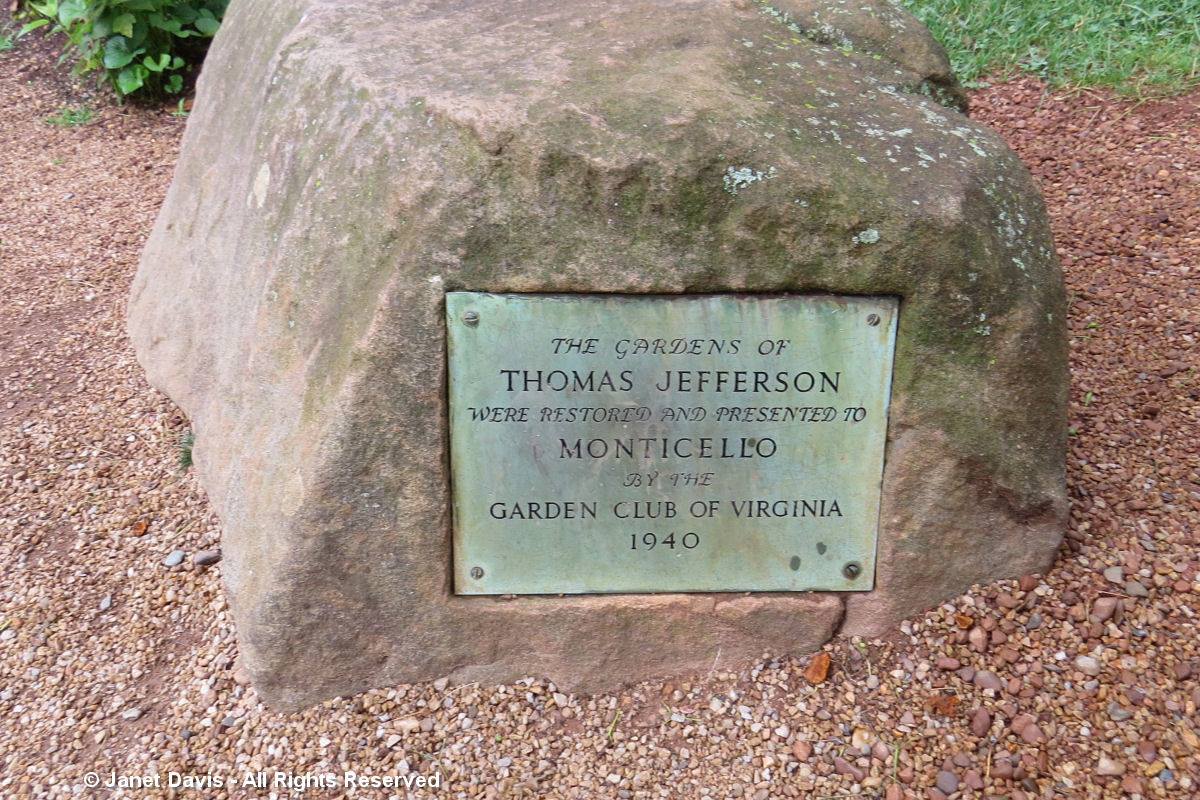

In 1808, around the main house, Jefferson built a series of flower gardens as well as a “winding walk”, its borders planted in 10-foot sections with an assortment of exotic and native flowers. As he wrote to his 16-year-old granddaughter Ann Carey Randolph in 1807, “I find that the limited number of our flower beds will too much restrain the variety of flowers in which we might wish to indulge, & therefore I have resumed an idea … of a winding walk … with a narrow border of flowers on each side. this would give us abundant room for a great variety”. But after his death, the flower gardens fell to ruin. In 1939-41, the Garden Club of Virginia….

….restored the walk and fish pond as a gift to Monticello. In order to determine the walk’s original shape, researchers parked their cars on the West Lawn and shone their headlights over it. The old outline appeared. Here we see lavender and sweet william (Dianthus barbatus), both plants recorded by Jefferson.

Here we are outside the main house, looking back through night-scented tobacco (Nicotiana). Jefferson preferred to have fragrant plants along the winding walk.

We see plants that were grown by him, including common mallow (Malva sylvestris).

Jefferson was proud of the native plants of Virginia – in fact 25 percent of his plants at Monticello were native – so it’s not a surprise to see butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa) and blackeyed susans (Rudbeckia hirta) mixed in with blue cornflowers (Centaurea cyanus) and rose campion (Lychnis coronaria).

THE VEGETABLE GARDEN & FRUITERY

When Jefferson spoke about his ‘garden’, he was referring to his vegetable garden. As he noted in 1819: “I have lived temperately, eating little animal food, and that … as a condiment for the vegetables, which constitute my principal diet.” After the decision was made in the late 1970s to recreate Monticello’s 1000-foot long by 80-foot wide, 2-acre vegetable garden….

…the process began in 1979 with a 2-year archaeological dig to corroborate the written history. The dig turned up parts of the garden’s stone wall and the foundation of the pretty garden pavilion seen below, which was a favourite place for Thomas Jefferson to read.

As the story goes, the garden pavilion – framed here by mulberry leaves — fell over soon after Jefferson’s died in 1826. It was restored in 1984.

Those mulberry leaves tell their own story, for they are part of Mulberry Row, the plantation lane at Monticello with 20 dwellings that formed the “center of work and domestic life for dozens of people – free whites, indentured servants, and enslaved people.” Here were the blacksmiths, carpenters, house joiners, stablemen, tinsmiths, weavers and spinners and domestic servants.

Parts of Mulberry Row have been restored, including this blacksmith & iron shop. Jefferson launched a nailery at Monticello, hoping to make it a thriving commercial enterprise. Young boys were destined to be nailers, as he wrote in his farm book: “Children till 10. years old to serve as nurses. From 10. to 16. the boys make nails, the girls spin. At 16. go into the ground or learn trades.”

This is a slave cabin on Mulberry Row.

I’m delighted to see bluebirds flying and perching along Mulberry Row. My first ever bluebird!

Going down the stairs to the vegetable garden, we begin our tour at the far end where a healthy crop of wheat is planted with sunflowers. When Jefferson inherited the plantation from his father, it was planted in tobacco. Following the American Revolution, Virginia ceased to be the dominant player in tobacco trade and the Napoleonic wars had also shifted the balance of agriculture in Europe. Tobacco cultivation also depleted the soil significantly. So when Jefferson returned to Monticello in 1793, he switched tobacco for wheat.

Corn is just ripening. Jefferson grew Indian corn in his garden in Paris when he served in the French legation.

This ‘Tennis Ball’ lettuce (Latuca sativa) is bolting, as it must when heritage seed is being saved. Thomas Jefferson said of this variety, which is one of the parents of buttery Boston lettuce: “it does not require so much care and attention.”

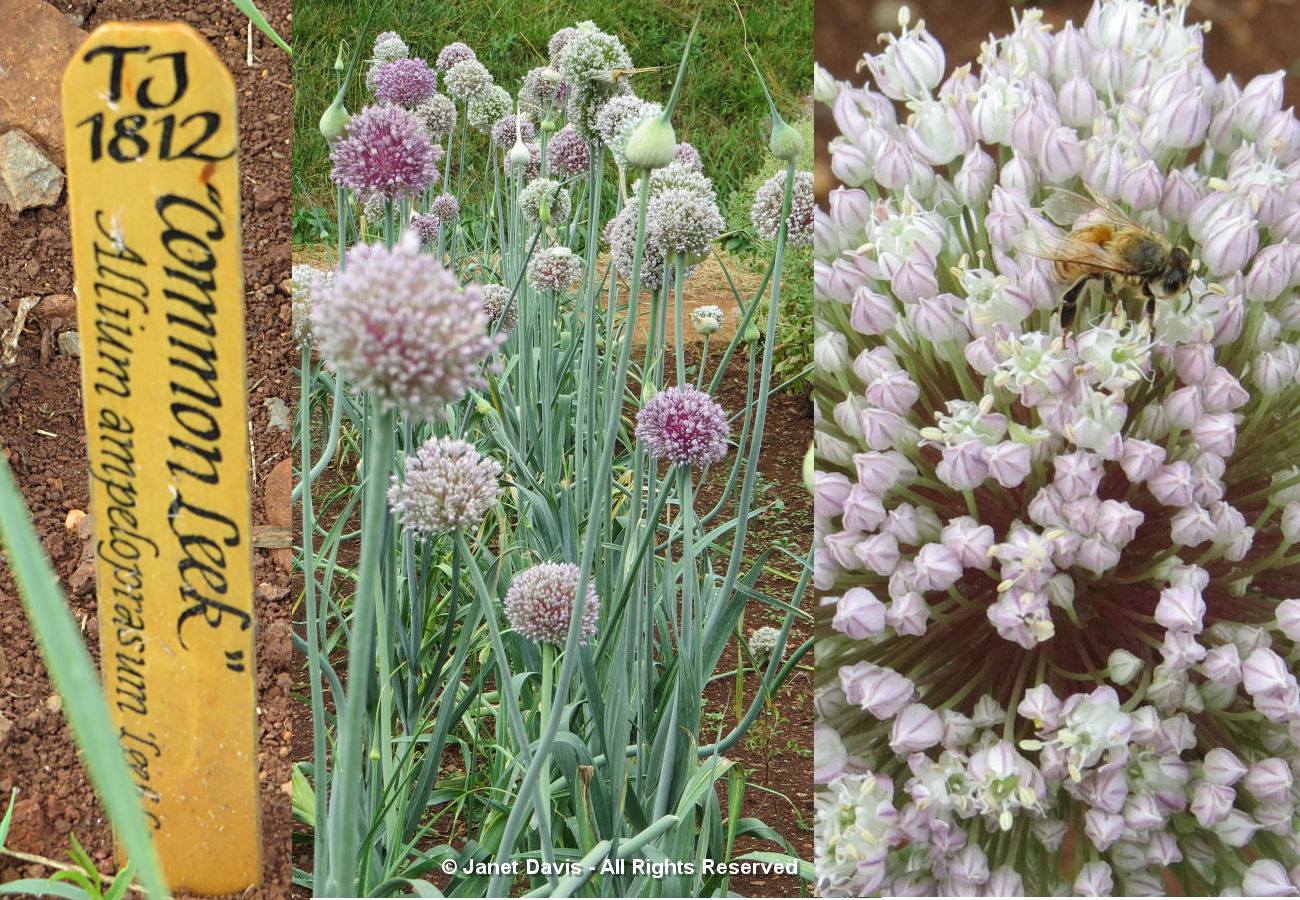

Leeks (Allium ameloprasum) are looking lovely – and are possibly the same Musselburgh leeks that Jefferson grew.

Jefferson loved sea kale (Crambe maritima) and blanched it under special terracotta cloches to produce tender leaves. According to Monticello, “Jefferson was probably inspired to grow sea kale after reading Bernard McMahon’s The American Gardener’s Calendar, 1806, sometimes called his “Bible” of horticulture.”

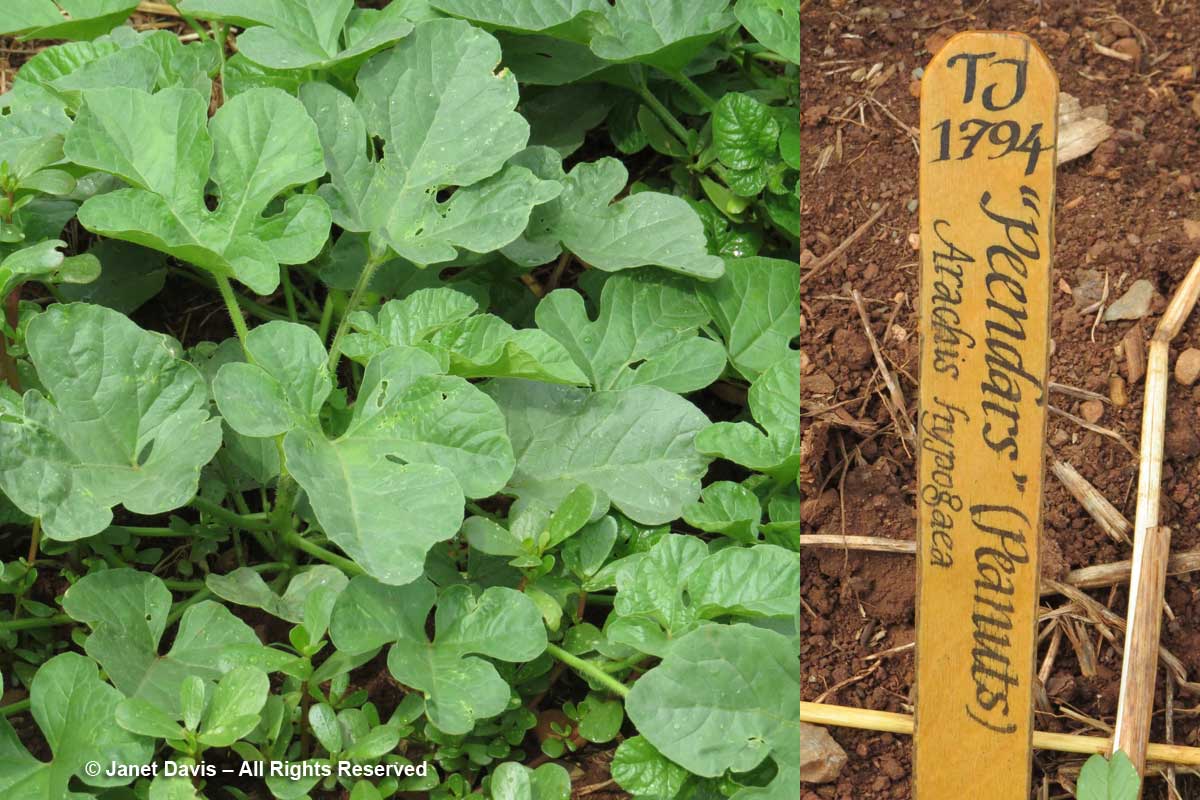

Peanuts catch my eye. In Andrew Smith’s book Peanuts: The Illustrious History of the Goober Pea, the author wrote “In his ‘Notes on the State of Virginia’, Thomas Jefferson wrote that peanuts grew in Virginia in 1781. Subsequently Jefferson planted sixty-five hills of ‘peendars’ which yielded 16-1/2 pounds ‘weighted green out of the ground which is ¼ pound each.’ While president, he reported that peanuts were very sweet.”

Here is chamomile (Anthemis nobilis).

Artichokes (Cynara scolymus) were one of the first vegetables Jefferson grew in his garden at Monticello in 1770, and successfully harvested in 13 of 22 years. “Artichoke” was also the keyword in the secret cipher code used in his communications with Meriweather Lewis of the Lewis & Clark Expedition.

Though they were still a somewhat new fashion in Virginia, Jefferson enjoyed his “tomatas”, the planting of which he recorded in his garden book from 1809 to 1824.

From the vegetable garden, I look down on the south orchard, where Jefferson once planted 1,031 fruit trees.

I see peaches ripening here. This succulent fruit was perhaps Jefferson’s most prized crop, and in 1794 he even grew 900 peach trees as field dividers at Monticello and another farm. He wrote to a friend: “I am endeavoring to make a collection of the choicest kinds of peaches for Monticello“. Of the 38 varieties he grew, he purchased many from American nurseries and was given Italian introductions by his Tuscan–born friend Philip Mazzei, whom he’d met in London and encouraged to emigrate to Virginia in 1755.

There’s a recreation of the Old Fruit Nursery here as well…..

… and the vineyards, below, all of which were part of what Jefferson called his “fruitery”.

In the distance, we see Montalto (the “high mountain”). It’s on this mountain where the descendants of Philip Mazzei will soon be harvesting grapes to make fine wine in a joint project with Monticello….

…under the guidance of longtime Virginia winemaker, Gabriele Rausse – whose vintage we pick up in the gift shop later.

I walk through the bean arbor, the scarlet runners just getting started, and head out of Monticello’s garden. It’s time to go down the mountain.

CEMETERY, WOODS AND VISITOR CENTER

Near the top is the family graveyard where Thomas Jefferson and his descendants (except for those of Sally Hemings) are buried.

The woods on the slope are cool and beautiful; trees tall and towering, the understory filled with redbuds (Cercis canadensis). A notable lover of trees, Jefferson allegedly once said: “I wish I was a despot that I might save the noble, beautiful trees that are daily falling sacrifice to the cupidity of their owners, or the necessity of the poor. . . .The unnecessary felling of a tree, perhaps the growth of centuries, seems to me a crime little short of murder.”

I’m enchanted by the birdsong echoing in the trees and make a short video. Have a listen….

We arrive back at the Visitor Center where we lunched earlier. The grounds are nicely landscaped…..

…… and the gift shop with its garden center is fabulous!

I say my farewell to Thomas Jefferson, noting the 10-1/2 inch difference in our heights. I thank him for his enterprising spirit, his love of nature, his gardens. He says nothing.

THE CENTER FOR HISTORIC PLANTS

Though it’s not open to the public except by appointment or for special posted events through the year, the Thomas Jefferson Center for Historic Plants (CHP) is a fundamental part of Monticello, maintaining many of the historic plants and providing them for the gift shop . It’s located below Monticello at Tufton Farm, part of the original Monticello estate – and a short distance down the road from our own Arcady Vineyard Bed & Breakfast, also part of the original Monticello estate. I make a phone call, explain that I’m in Virginia to begin a Blogger’s Fling in a few days, and would love to visit. A short time later, I’m met by Jessica Bryars, acting manager at CHP (whose other job is to manage the fruitery at Monticello).

We tour the farm, beginning in the nursery filled with young herbaceous plants.

Shrubs and roses are in hoop beds outside.

There are many beehives here, protected from honey-loving black bears by electric fences.

The garden, its grass pathway flanked by flower borders is lovely. Though most of the plants are historic, a few, like annual purple Verbena bonariensis are included…..

….making the pipevine swallowtail happy.

I spot Lilium superbum, the lovely native Turks-cap lily.

Here’s a little taste of a pretty corner at CHP (and yes, there are hummingbirds as well as bluebirds at Monticello).

Monticello’s future contains plans for a ‘21st century farm’ on the Tufton farm site, a notion that I think would bring a great deal of young tourism to this part of Virginia, including people who aren’t much drawn to historic recreations of 200-year old presidential gardens. And I suspect the great experimenter Thomas Jefferson, whose own namesake plant twinleaf (Jeffersonia diphylla) grows here and flowers in spring, would agree.

UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA

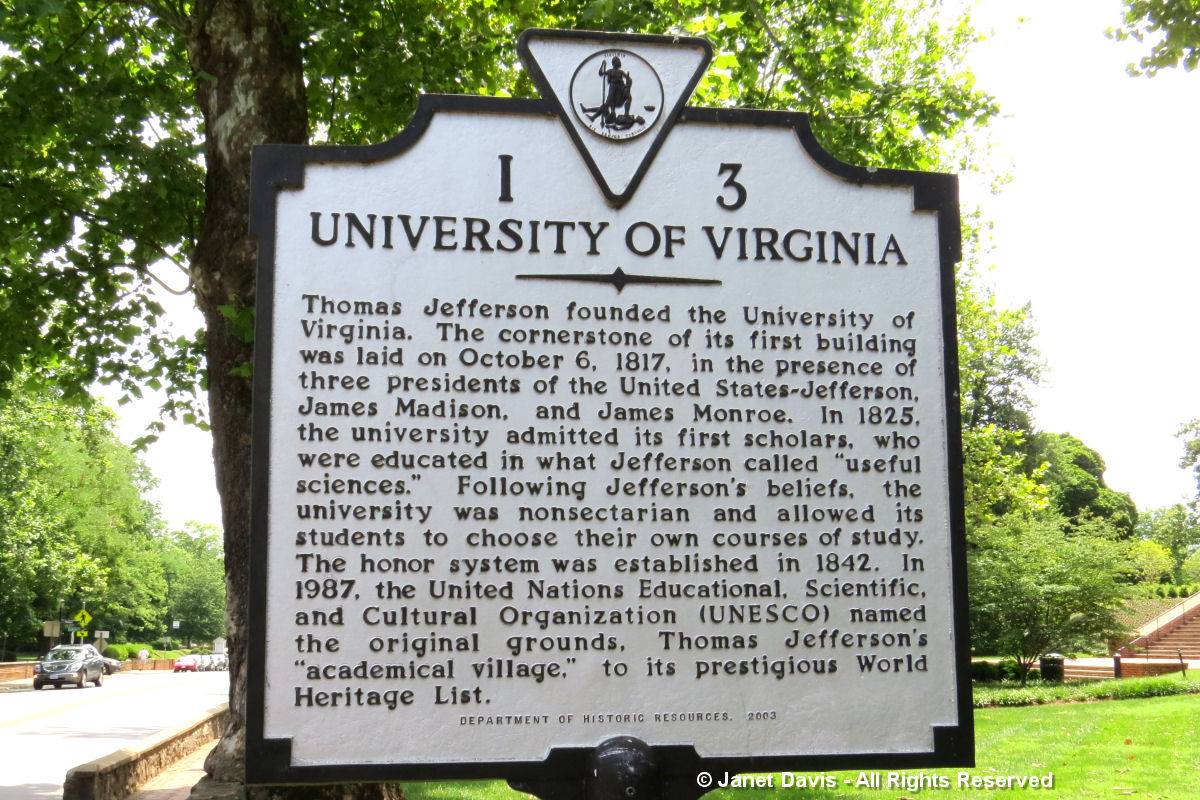

In order to round out our understanding of Thomas Jefferson’s influence on the region, we visit the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, which is most definitely a ‘university town’. As the historic plaque below says, it was founded by Jefferson in 1817 in the presence of his two good friends, James Madison and sitting president James Monroe.

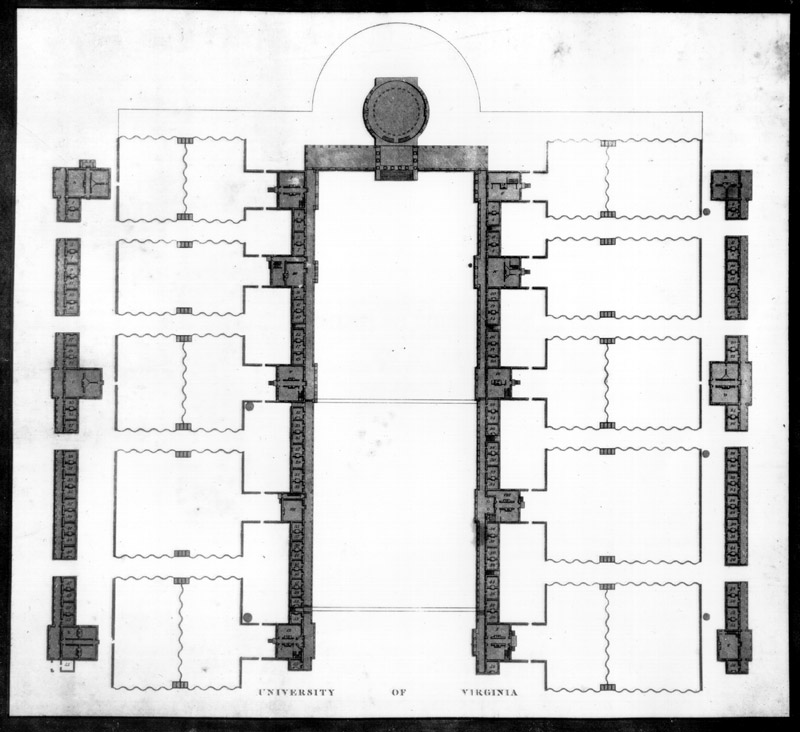

Jefferson designed UVA as an ‘Academical Village’, with a beautiful rotunda at one end of ‘The Lawn’ flanked by pavilons containing lecture halls and undergraduate and faculty apartments. This is an 1826 Peter Maverick engraving of Jefferson’s original plan.

Jeffferson’s rotunda was Palladian in design, similar to that of his home at Monticello. It was inspired by the Pantheon in Rome and housed a library, rather than a church, as was then common in universities. This reflected Thomas Jefferson’s personal secular beliefs, which were moral without being religious. (In 1820, he reworked his own bible, carefully cutting out all the parts he disdained and leaving in an 80-page version he published as The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth.) Sadly, Jefferson’s rotunda burned down in 1895.

Today’s rotunda is an historically-correct modification of the Stanford White recreation.

The beautiful pavilions below are original. This is what Jefferson wrote in 1817 to William Thornton, the architect of the U.S. Capitol, as he was researching his design. “What we wish is that these pavilions, as they will show themselves above the dormitories, shall be models of taste and good architecture, and of a variety of appearance, no two alike, so as to serve as specimens for the architectural lecturer. Will you set your imagination to work, and sketch some designs for us, no matter how loosely with the pen, without the trouble of referring to scale or rule, for we want nothing but the outline of the architecture, as the internal must be arranged according to local convenience? A few sketches, such as may not take you a minute, will greatly oblige us.”

As we stroll the campus in the heat of a June afternoon, we listen to UVA undergrads addressing small groups of high school students and their parents on their pre-college selection tours. In the shade of tall trees on The Lawn, one co-ed laughingly tells her group about Halloween dress-up traditions on campus. Near Cabell Hall, another warns the students that the UVA basketball team is so popular and the stadium so small, a lottery system has been devised to distribute tickets equitably. One can only imagine Thomas Jefferson standing nearby listening, perhaps striding forward to join the young people. Perhaps offering this …. “Determine never to be idle. No person will have occasion to complain of the want of time who never loses any. It is wonderful how much can be done if we are always doing.”

Indeed, it is wonderful how much can be done.