A few weeks ago, I began to write a blog on Allium cristophii, whose common name is star-of-Persia or Persian onion. As it’s now early autumn and bulb-buying time is on our gardening calendars, I wanted to share some images I’ve made over the years that show this ornamental onion as an unusual, but beautiful, component in a series of late-spring/early-summer plant vignettes, including the one below showing it cavorting with Astrantia major ‘Roma’ at the Toronto Botanical Garden. But in order to provide as much taxonomic background as possible, I began to dig a little into the history of the plant – an excavation that became either a dark pit or a productive mine, depending on how one views botanical trivia as an obsession.

As a somewhat ‘mature’ gardener, I remember when bulbs were often found for sale as Allium albopilosum C.H. Wright, referring to the white hairs on the leaves. That taxon was assigned to a herbarium specimen in 1903 by Kew herbarium assistant Charles Henry Wright, and describes the lovely illustration below, which was made in 1904 by John Nugent Fitch for Joseph Hooker’s Curtis’s Botanical Magazine (Volume 130, ser. 3 nr. 60 tabl. 7982). However, the name was rejected in 1995 as a synonym by Kew taxonomist Rafael Govaërts, in favour of Allium cristophii subsp. cristophii Trautv. (for Ernst Rudolf von Trautvetter 1809-1889, Russian botanist and former director of the Botanical Garden in St. Petersburg).

Fair enough. All who are familiar with the plant know it as Allium cristophii these days, though it is almost always misspelled in the trade as “christophii”. Perhaps it’s that irritating lack of accuracy that made me look more deeply into the history of the plant. Who was “Cristoph”? How was he related to Trautvetter? And therein, as Winston Churchill once said of Russia, “is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” Interestingly, Russia figures in the plant’s nomenclature, for its earliest basonym, Allium bodeanum Regel , honours the Russian diplomat Baron Clément Augustus Gregory Peter Louis de Bode, first secretary to the Russian legation in Persia (now Iran). In 1845, he published a 2-volume memoir titled Travels in Lúristán and Arabistán. It’s available online via Google books, so naturally, I spent the better part of a few days skimming his rich account of his 67 day winter journey (December 23, 1840-February 28, 1841) from Tehran through Persia and back to Tehran – a journey of 353 farsangs (that’s the distance at which you can tell if a camel is white or black) or 1253 miles. I was looking for mention of the allium, of course, and though I knew the dates could not possibly agree with its flowering time, I was nevertheless intrigued to read his observation in this little passage, on pages 376-378 of Volume I, about another bulbous plant from the region, which is likely either a Puschkinia or Chionodoxa (now Scilla), given the “blue and white flower” and its early emergence alongside narcissus (likely N. tazetta). More importantly, it establishes his close relationship with Friedrich von Fischer, director of the St. Petersburg Botanical Garden – and presumably the consignee of bulbs of star-of-Persia gathered by de Bode at some other time.

Pg. 376, Volume I – (January 31, 1840). “At a quarter past nine, the village of Bú-l-feriz became discernible in the direction north by NNE. At half past nine, we crossed the river of Bú-l-feriz. At a quarter past ten am, we turned to NNW by NW, and passed by the remains of some stone walls. At three-quarters past ten, we crossed two rivulets, the second was a stream of some size, but both were overgrown with high reeds (kamish). At eleven am, our party ascended a hill, and went along a high table land with traces of cultivated ground and former habitations. It had been inhabited by the Bú-l-ferizi, who not able to resist the encroachments of the Bahmeï, had deserted the spot and removed near Behbehán.

The meadows are covered with narcissus and another bulbous plant with a root as large as a strong muscular fist, and called by the natives piyáz (onion), ‘unsul, or piyázi Gúristan, because it sometimes grows among tombs. This plant is known to the Persian apothecaries, and used, if I recollect right, as an astringent. The late Hakim Bashi of the Shah ‘Mirza-Baba, (a man esteemed and honoured by all who knew him), requested me before I set out on my journey, to procure him, if possible, some bulbs of this plant. which I did, and at the same time, sent a few to Mr. Fisher* (sic), the Director of the Botanical Gardens at St. Petersburg. I have since had the pleasure of seeing one of these plants thriving under the assiduous care of that gentleman. I am told that it bears a blue and white flower.” (* Friedrich Ernst Ludwig von Fischer (1782-1854) was a German-born Russian botanist and the director of the St. Petersburg Botanical Garden from 1823-1850.)

So that I don’t bore you completely with taxonomy, let’s have a brief pictorial interlude from our lovely allium – here with June peonies at Toronto’s Spadina House Museum & Gardens.

Leaving aside Baron de Bode and Allium bodeanum, whose collection details either went unrecorded or are buried in the 19th century papers at the St. Petersburg Botanical Garden, let’s move on to the name Allium cristophii. Its first record (written as “Cristophi”) was published by botanist Ernst Rudolf Von Trautvetter in the Russian botanical journal Trudy Imperatorskago S.-Peterburgskago botanicheskago sada.Acta Horti etropolitani – Volume 9, 1884, page 268. Interestingly, though the plant is listed with description of the parts preserved in the herbarium, Trautvetter’s record of its supposed discovery is not exactly a glowing paean to the mysterious Dr. Cristoph. For it reads in Latin, “Allium Cristophi Trautv. (Molium Rgl.All. p 12) – Dubium est utrum in Turcomania australi anne in Karabach species haec a Cristoph reperta sit.” There are a few ways to translate this cryptic comment, but let’s go with this: “It’s doubtful that (or whether) this species was discovered by Cristoph in south Turkomania (or) in Karabach.” So, where does that leave us? Is Trautvetter doubting that Cristoph found it in either of those places, or that Cristoph found it at all? Again, a mystery inside an enigma – since it sheds no light on “Cristoph”. And yes, it would be nice to know who the man is, given how lovely his namesake looks with Geranium psilostemon, seen here in the third week of June at Vancouver’s Van Dusen Botanical Garden.

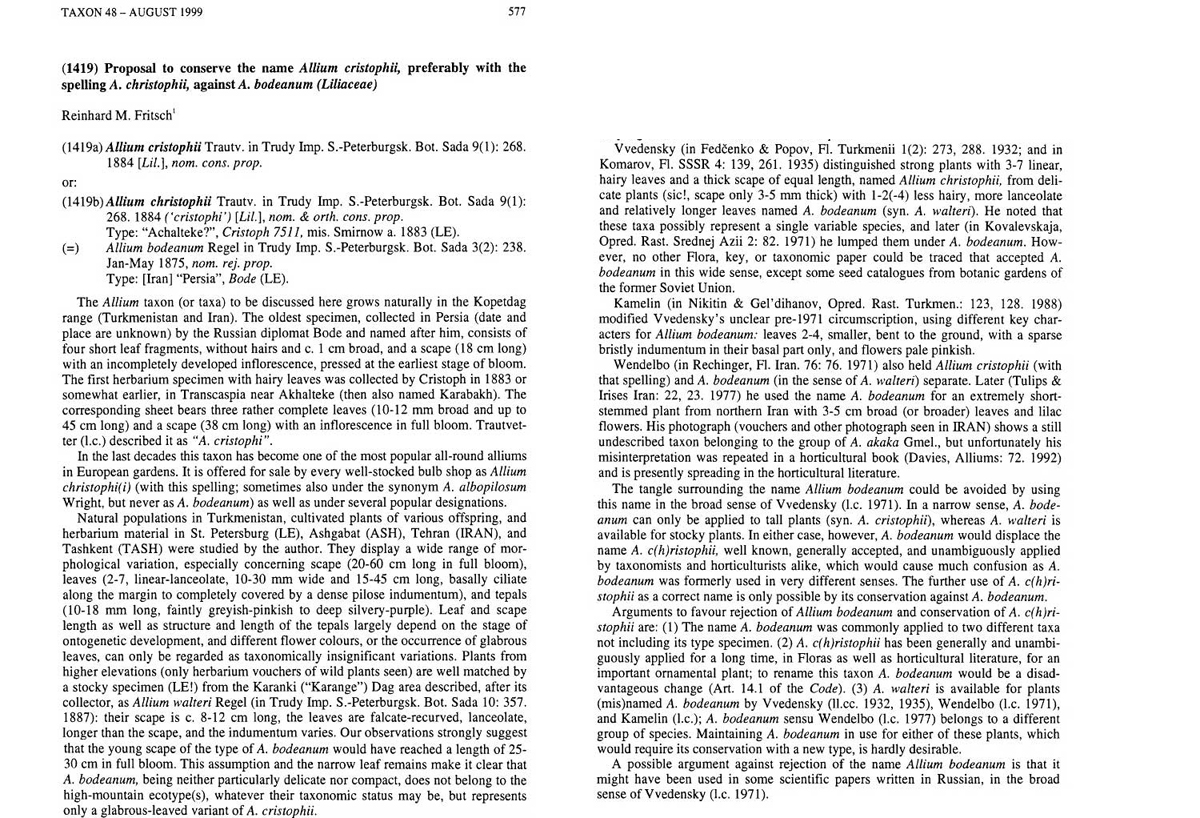

Certainly, the most knowledgeable contemporary taxonomist working with the genus Allium is Reinhard M. Fritsch of the Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research at Gatersleben, Germany. It was he who proposed conserving A. cristophii Trautv. against A. bodeanum Regel (in Taxon 48, August 1999, Item 1419, page 577), though his bid to change the name to “christophii” based on common usage, was rejected. The following capture of the page shows the taxonomic history. The part that interested me is: “The first herbarium specimen with hairy leaves was collected by Cristoph in 1883 or somewhat earlier, in Transcaspia near Akhalteke (then also named Karabakh). The corresponding sheet bears three rather complete leaves (10-12 mm broad and up to 45 cm long) and a scape (38 cm long) with an inflorescence in full bloom. Trautvetter (l.c.) described it as “A. cristophi”.” But who was Cristoph?

In 2013, Fritsch co-authored a comprehensive treatise on alliums with the exciting title A Taxonomic Review of Allium subg. Melanocrommyum in Iran. Allium cristophii, say the authors, “is an extremely polymorphous taxon especially concerning shape and density of indumentums of leaf laminae, length and diameter of scapes, dimension and density of inflorescences, as well as shape and color of tepals.” This statement accurately reflects what I’ve found so fascinating about Allium cristophii, having observed it in numerous gardens. Sometimes the starry flowers are silvery-lilac, other times they’re much more violet; sometimes they rest on squat, short stems, like this one, barely reaching the top of hosta leaves, at Toronto’s Casa Loma…..

….or hosting a clambering Clematis integrifolia, standing no more than 30-45 cm (12-18 inches) tall…

…while in other situations, the bulbs can grow decidedly taller, to 60-90 cm (60-90 inches), as with Geranium pratense here at Spadina House. This seems to be one of the vagaries of the species, and what you get with one bulb purchase isn’t necessarily what you’ll get with another.

Nonetheless, such a strikingly large inflorescence can look completely awkward on its own, and star-of-Persia definitely needs company to show off its merits. It’s even fun popping up through a shrub, as with this Spiraea japonica ‘Little Princess’ at Van Dusen Gardens.

Other beautiful companions include catmint (Nepeta racemosa ‘Walker’s Low’), shown here at the Toronto Botanical Garden.

Meadow sage (Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’) is a perfect June partner, also at the Toronto Botanical Garden.

Grasses make great pairings with alliums, and A. cristophii is no exception. Here it is at Van Dusen Gardens with Bowles’ golden grass (Milium effusum ‘Aureum’), illustrating the fact that purples and chartreuse/limes always make good partners.

And how great is this combination, star-of-Persia held in the embrace of variegated Chinese maiden grass (Miscanthus sinensis ‘Variegatus’) at the Toronto Botanical Garden?

As with all the ornamental onions, of course, Allium cristophii offers abundant nectar for bees, especially honey bees.

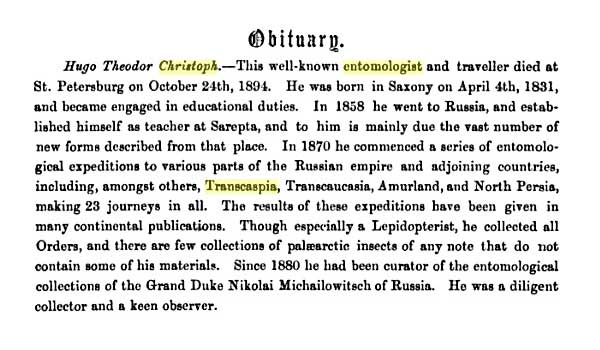

But it still bothered me. Who was “Cristoph”? In describing the etymology of the specific epithet, Fritsch and Abbasi write: “Dr. Cristoph was a physician and plant collector travelling in the Caucasus, North Iran, Transcaspia…” Perhaps, but his name did not emerge amongst the plant collectors at the time. And misinformation, as always, abounds on the internet. An online company called Seedaholic says: “The first herbarium specimen with hairy leaves was collected by Eugenius Johann Christoph Esper (1742-1810), a German entomologist in 1883.” Despite the obvious difficulty of collecting herbarium samples in remote regions more than 70 years after you’ve died, it seemed more likely that Trautvetter was referring to a plant collector associated with Russia or St. Petersburg. (And it’s comforting to know that I’m not the only obsessive who’s gone on record looking for the mysterious Dr. Cristoph. You should be able to click to translate from Dutch to English. She & I came to the same conclusion, independently. ) So I kept digging; perhaps Cristoph wasn’t a plant collector, but was indeed an entomologist. Then this obituary popped up, from a Google books scan of the Entomologists Monthly magazine, Vols. 30-31. Could Hugo Theodor Christoph (1831-1894) be the mysterious “Cristoph”? The dates fit for 1885, and he was collecting in Transcaspia for Russia. Along with butterflies, might he have gathered a starry onion? And was his name misspelled by Trautvetter, back in St. Petersburg?

If for no other reason than giving him his historic due, I’d love to discover the identity of this mysterious “doctor” whose name is attached to one of the most interesting of the ornamental onions, a bulb whose starry spheres add just the right touch to romantic June garden vignettes like the one below, at the Toronto Botanical Garden.

So, Dr. Cristoph — or Dr. Christoph — whoever you were, here’s to you!