As part of my series on spring trees and shrubs, I thought it might be fun to take a deep dive into some of the many magnolias I’ve encountered during my garden travels over the past three-plus decades. As I said to someone, “I spend a lot of time writing about useful sparrows. Every now and then, I like to focus on the peacocks.” And magnolias, like peacocks, were precious cargo for the earliest botanical explorers collecting seeds and cuttings from far-flung shores.

By the time Carl Linnaeus published Species Plantarum in 1753, thereby assigning binomials (two-word Latin names) to the known plants of the world, Pierre Magnol, the highly respected director of the botanical garden at Montpellier in southern France had been dead for thirty eight years. But Magnol had been honoured in 1703 by botanist Charles Plumier in the naming of a West Indies magnolia, M. dodecapetala.

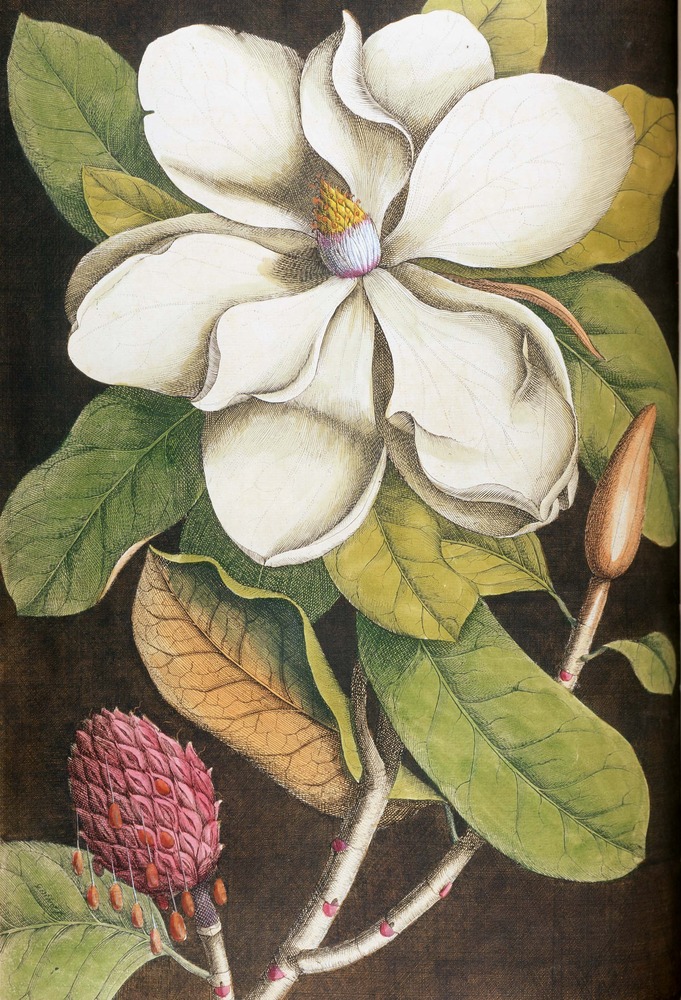

It was a time of discovery in the New World, as plant explorers visited the American colonies, sending back seeds and plants in Wardian cases. One of those explorers, Mark Catesby, travelled through Virginia and Carolina from 1722 to 1726, tramping through swampy woods and finding a magnificent tree with large, waxy, lemon-scented, white flowers which he called the Laurel Leaved Tulip Tree or Carolina Laurel. He made a preparatory drawing of the tree which came back with him to England in a trunk, along with drawings of many other plants and a few seeds and herbarium specimens. His drawings were the first Europeans had seen of plants and birds of North America. Some were repainted by other artists, then engraved as plates and published in ten parts from 1729-1748 in a collection called Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. Thus was Catesby’s Laurel Tree of Carolina, Magnolia altissima, flore ingenti candido, later named simply Magnolia grandiflora by Linnaeus – memorialized in 1744 in the hand-coloured etching, below, by Georg Dionysius Ehret.

Today we know this beautiful species as southern magnolia. I found it in bloom in the Beatrix Farrand-designed landscape at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C., now owned by Harvard University. I wrote a blog about my June 2017 visit to this spectacular garden.

Southern magnolia has made its way around the world, including an old specimen in the garden at Akaunui Farm Homestead in New Zealand, which I blogged about in 2018. The tree grows 60-80 ft tall (18-24 m) and 30-40 ft (9-12 m) wide, though some in Mississippi have reached 120 ft (36 m) in height.

And it was on fragrant southern magnolia flowers near the beach in New Zealand where I found honey bees feverishly gathering pollen from the stamens.

Magnolias feature a cone-like aggregate fruit called a “follicetum”, like the one below from M. grandiflora.

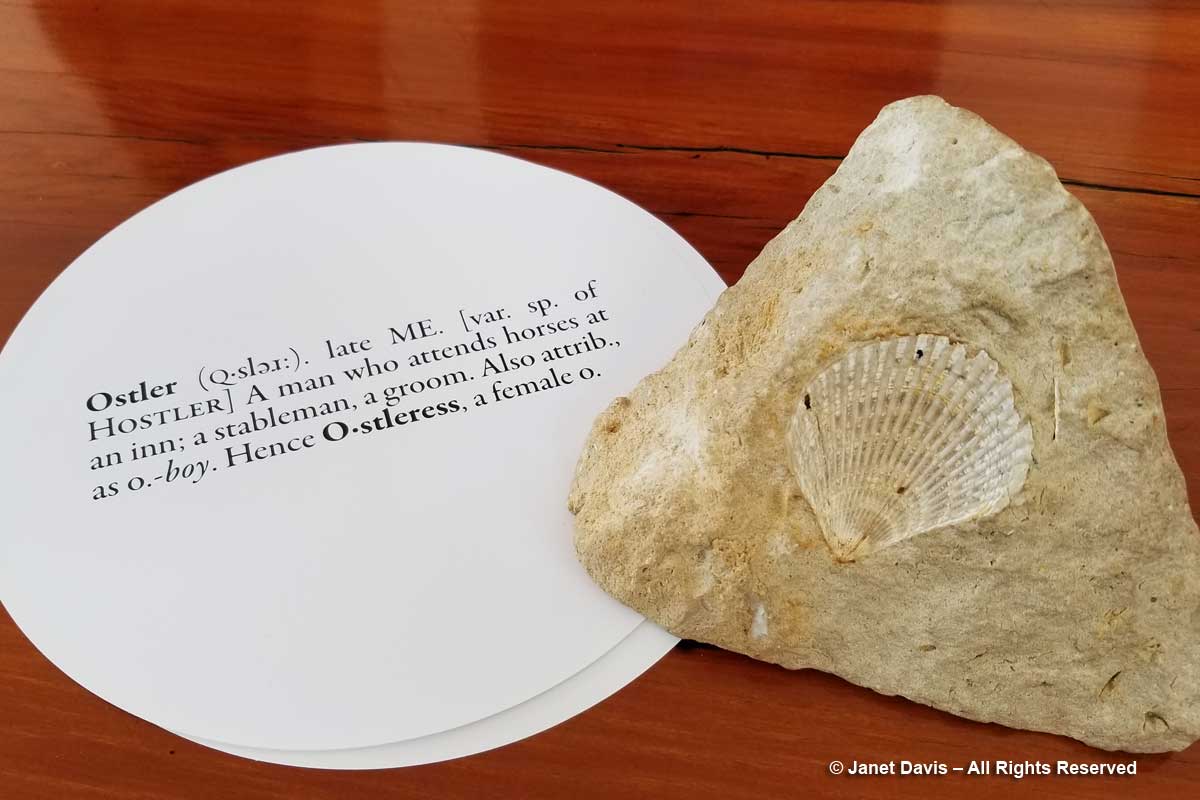

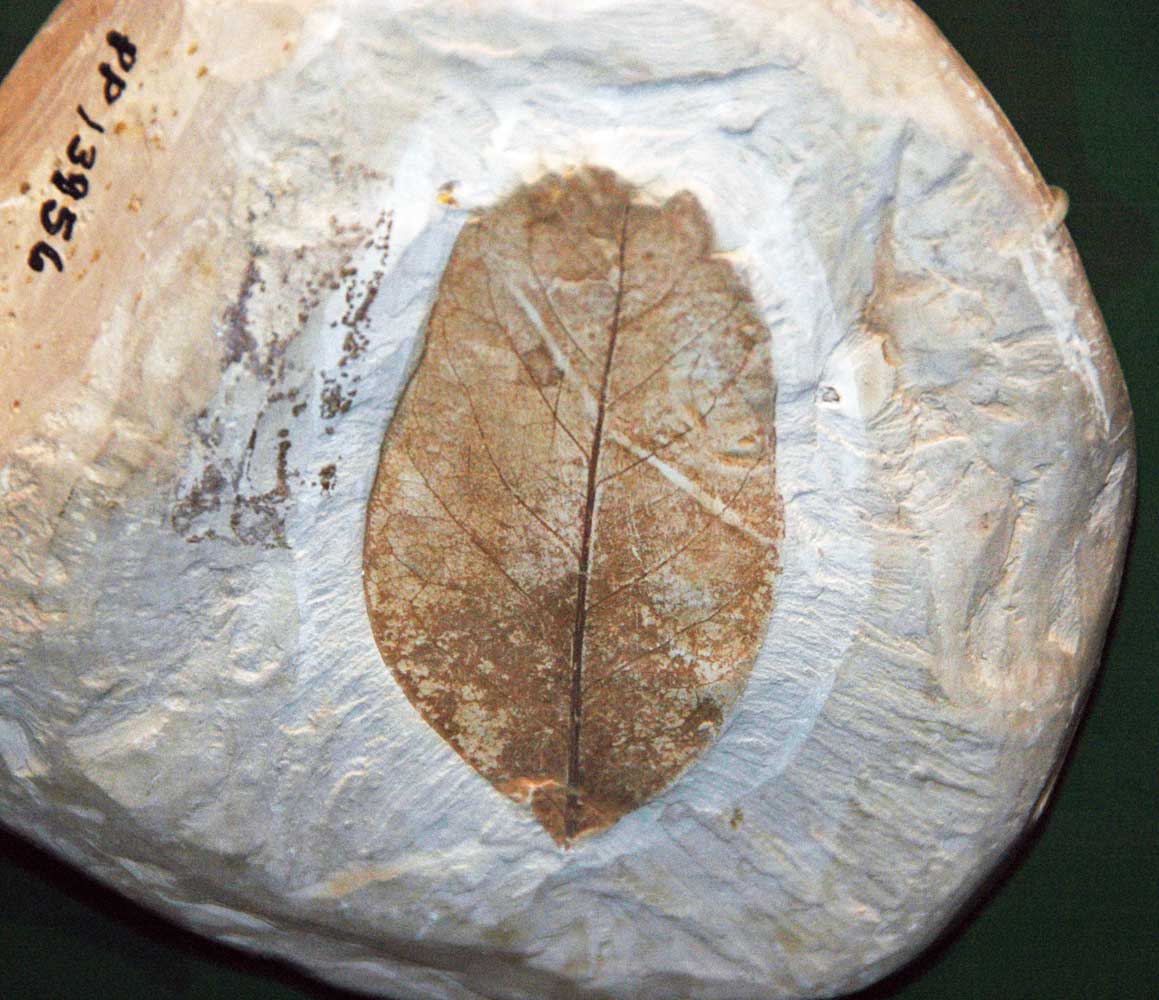

Magnolia ancestors are among the most primitive plants, having evolved in the Cretaceous (145-66 million years ago) with the dinosaurs, and they ranged in places far from where we find them today. Wrote John Fisher in The Origins of Garden Plants, “the climate in the northern hemisphere remained mild, and magnolias, bread fruit and camphor trees flourished on the west coast of Greenland – 300 miles north of the Arctic Circle.” This is a photo by Geology Professor James St. John shared under Creative Commons Attribution of a fossil leaf of extinct Magnolia boulayana, from the Cretaceous flora of Alabama, USA from the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL.

Though we cannot grow southern magnolia in Toronto, we can enjoy its leathery, bronze-backed leaves in winter arrangements like the ones below, on my back deck.

But Magnolia grandiflora was not the first American magnolia species to cross the Atlantic. The Bishop of London and head of the Anglican church in the American colonies, Henry Compton, had a garden at Fulham Palace and was an avid collector of rarities. He sent the missionary John Banister to Virginia in 1678; in the coming years, he would prepare a catalogue that represented the first survey of native American plants. One of his discoveries was the sweetbay, Magnolia virginiana, with creamy scented flowers. It was used medicinally by the native Indian tribes of the southeast, who prepared decoctions to treat rheumatism, fever and consumption. It would become the first of the genus to be successfully grown in Britain. I found M. virginiana ‘Green Shadow’ below, growing on New York’s High Line.

I also found another native American magnolia on the High Line: M. macrophylla var. ashei, Ashe’s magnolia, below. Closely related to the taller bigleaf magnolia (M. macrophylla), it was named for William Willard Ashe (1872-1932) of the U.S. Forest Service. Though we often think of Dutch designer Piet Oudolf as a creator of four-season meadows, he is also skilled at using regionally native shrubs and trees for specific applications in his designs.

Beetles are considered to be the evolutionary pollinators of magnolias, since the plants evolved in the Cretaceous before bees appeared. But bees certainly take advantage of the flowers, as we see below with a native megachile leafcutter bee foraging on Ashe’s magnolia.

The only magnolia native to Canada – or at least the Carolinian Forest in extreme southern Ontario where it is listed as ‘endangered’ – is cucumber tree (Magnolia acuminata var. acuminata). Though it does not grow in the wild near me in Toronto, it is nonetheless hardy here and there is a lovely specimen in the 200-acre Mount Pleasant Cemetery, below. It is much smaller than its southern counterparts which can reach 80 ft (25 m). Cucumber magnolia is morphologically variable, and the southern form, M. acuminata var. sub cordata, has been used in breeding with Asian magnolias to produce many of the highly prized yellow cultivars below.

The flowers of cucumber magnolia are unusual looking with green outer tepals cupped around yellow inner tepals. They close at night.

The tree gets its common name from the cucumber-like appearance of the unripe fruit, which turns red in late summer.

Enter the Asian Magnolias

The first popular magnolia resulting from a 1956 cross of cucumber magnolia with the white-flowered Chinese Yulan magnolia (M. denudata) was called ‘Elizabeth’. Created by Dr. Evamaria Sberber at the Brooklyn Botanical Garden…..

…. its soft-yellow, precocious flowers (i.e.appearing before the leaves) marked a new chapter for magnolias.

But breeders wanted even brighter, longer-lasting yellows. This is the beautiful ‘Butterflies’, a 1990 cross of M, acuminata ‘Fertile Myrtle’ x M. denudata ‘Sawada’s Cream’ by famed Michigan magnolia breeder Phil Savage.

My photos of ‘Butterflies’, below, illustrate the reproductive strategy of magnolias. The flowers are protogynous, meaning the flowers open initially in the female phase during which the curved stigmas are receptive (top). They then close, only to reopen with the male reproductive organs, the pink-tipped stamens, ready to shed pollen (bottom). Magnolias evolved this system to improve the chance of cross-pollination, rather than self-pollination, thus strengthening the genetic diversity.

I have blogged previously about the wonderful yellow magnolias in the collection of the Montreal Botanical Garden – see “Mellow Yellow Magnolias” – so I won’t repeat myself here, other than to offer this montage of a selection of those beauties.

1- ‘Golden Sun’, 2 -‘Maxine Merrill’, 3-‘Banana Split’, 4-‘Yellow Bird’, 5-‘Golden Goblet’, 6-‘Sunburst’, 7-‘Limelight’, 8-‘Golden Endeavour’, 9 -‘Tranquility’

There are a number of hardy Asian magnolias for our climate (USDA Zone 5–Can. Zone 6), though their early flowering sometimes coincides with a spring frost. Native to Japan and Korea, the Kobushi magnolia, Magnolia kobus var. kobus, is a small tree or large shrub that grows 25-50 ft tall (8-15 m) with a wide spread. I have photographed specimens in Toronto’s Mount Pleasant Cemetery and at the Royal Botanical Garden in Burlington, ON, below.

The white flowers of M. kobus are considered by some to be the most fragrant of the early magnolias. According to Helen Van Pelt Wilson and Léonie Bell in their book The Fragrant Year, the blooms distill “the ripe mango aroma of orange and pineapple softened by a note of lily, a perfume noticeable many yards away. Later the glossy leaves and gray twigs, crushed, have the spiciness of bayberry.”

The lovely star magnolia from Japan, Magnolia stellata, is related to M. kobus (some botanists consider it a variety) and a good choice as a tree or shrub for a small garden, given it usually doesn’t grow taller than 10 feet (3 m) with a spread of 15 feet (4.6 m). It bears at least 12 ribbon-like tepals, usually white but with natural variants such as var. rosea and var. rubra of pale rose to pink. When I was a young girl in the suburbs outside Vancouver, BC, my mother grew a star magnolia outside my bedroom window. It had a light perfume, one that Wilson and Bell describe as “watermelon or honeydew blended with Easter lily.”

I photographed one of the more bizarre design uses for star magnolia one spring at Ontario’s Royal Botanical Garden in their “hedge plants” area.

Ask most gardeners in the northeast what their favourite magnolia is and they’ll likely describe the ‘tulip tree’ or the ‘saucer magnolia’, both names for the widely available, hardy hybrid Magnolia x soulangeana. Now almost two centuries old, it is reported to have appeared in 1826 in the garden of M. Soulange-Boudin at Fromont near Paris, an accidental cross between two Chinese species, the pure white Yulan, M. denudata and the mulberry coloured Mulan, M. liliiflora. On a well-grown shrub, those upturned rose-pink goblets are utterly enchanting in early spring, just when winter-weary gardeners are starved for beauty.

There are beautiful, mature specimens in Toronto’s Mount Pleasant Cemetery, usually flowering in mid-late April, the same time as the early Japanese cherries and native plums, depending on the season. The oldest specimens reach 15-20ft (4.6-6 m) with a large spread.

I believe this is the cultivar M. x soulangeana ‘Lennei Alba’, introduced in 1931 by Terra Nova Nurseries in Holland.

Saucer magnolias can be found throughout the temperate world. I photographed ‘Verbanica’, below, an 1873 introduction from France at Van Dusen Botanical Garden on May 2, 2017. Note that its later flowering has also meant that the flowers are not ‘precocious’, i.e. the leaves have also emerged.

In warm climates, M. x soulangeana often flowers in winter. I photographed ‘Lilliputian’, below, bred for its miniature form and flower size, at the Los Angeles County Arboretum on January 6, 2018.

Now for my personal favourites, the Loebner hybrids, so-named because they were first created in the early 1900s from crosses between the Japanese species Magnolia kobus and M. stellata by renowned German horticulturist Max Löbner (1869-1947). The one I admire each spring at the Toronto Botanical Garden, below, is the white-flowered cultivar ‘Merrill’. It was grown from open-pollinated seed in 1939 by a student of research scientist and professor of genetics Karl Sax at Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum. Sax named the cultivar in 1952 for the retiring Arboretum director Elmer Merrill, whom Sax would replace as director.

Unlike its slow-growing star magnolia parent, ‘Merrill’ grows quickly to a mature height of 20-30 ft (6-9 m), i.e. less than M. kobus. The large, slightly fragrant flowers that appear on the bare branches are white flushed with pink, the tepals slightly broader than those of star magnolia. It is truly lovely.

My other favourite Loebner hybrid is pink-flowered ‘Leonard Messel’. An award-winning 1955 cross between M. kobus and M. stellata var. rosea from Nymans Garden in Sussex, England, home of the Messel family, this cultivar has more of star magnolia’s dainty appearance, its pink, ribbon-like tepals fluttering in the breeze. At the Toronto Botanical Garden, there are two shrubs, including this one in a sheltered corner on an inner terrace.

I have been known to spend long minutes focusing on the enchanting blooms……

….. that emerge like floral Cinderellas from the fuzzy brown winter buds.

There are also a few ‘Leonard Messel’ magnolias at Mount Pleasant Cemetery, growing in relatively unprotected sites.

Now for the bad news: f-r-e-e-z-i-n-g. Unlike plants adapted to growing in sub-zero climates, Japanese magnolias hail from mountain regions where their flowering is timed with the onset of mild spring temperatures. In Ontario, you can have an early spring in March that teases open magnolias, then snows on them, as it did with M. x soulangeana at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in April 2002…

….. or turns those March 2012 ‘Merrill’ flowers in my photo above to brown mush four days later. So a little caveat emptor is in order with magnolias.

The Oyama magnolia, Magnolia sieboldii, with its bright red stamens made its way quite dramatically from Japan to Europe with the German botanist and doctor, Philipp Franz von Siebold, physician to the Governor of the Dutch East India Company. An eye surgeon who could remove cataracts, he had arrived in 1823 and therefore initially found popularity with government officials. He lived with his Japanese mistress with him he had a child and gardened with his newly found plants on the man-made port island of Dejima in Nagasaki prefecture. But when it was discovered that he had procured maps of the mainland, he was charged with espionage and imprisoned for a year. He was expelled in 1830 and was permitted to take his plants with him (including Hosta plantaginea, Corylopsis spicata, Clematis florida var. sieboldii, Fatsia japonica, Hamamelis japonica), but left his mistress and child behind. If this sounds like a fairytale, in fact Puccini’s 1904 opera ‘Madama Butterfly’ is based on von Siebold’s travails. As for Magnolia sieboldii, it is a beautiful small (10 ft – 3 m) woodland shrub for light shade and marginally hardy in Toronto where I have photographed it in June, but it thrives in milder parts of Canada.

The ‘Girl’ Series of hybrid magnolias were developed in 1955-56 at the U.S. National Arboretum by William F. Kosar and Dr. Francis de Vos. They involved crosses of one of two of the Magnolia lilliflora (the Mulan or woody orchid magnolia) cultivars ‘Nigra’ (below) and ‘Reflorescens’ and one of two Magnolia stellata cultivars ‘Rosea’ (var rosea) and ‘Waterlily’.

The resulting sterile hybrids, released in 1968, were named for the daughters of Kosar (‘Betty’) and de Vos (‘Ann’, ‘Judy’, ‘Randy’, ‘Ricki’); the daughter of Arboretum director Henry Skinner (‘Susan’); and the wife of U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman (‘Jane’). Flowering 2-4 weeks later than M. stellata and M. x soulangeana, they are less at risk from late spring frost that will damage the flowers. Of the ones I’ve included below in this blog, ‘Ricki’ and ‘Ann’ are the shortest (10-12 ft or 3-3.6 m) with a 16-ft (4.8 m) width; ‘Jane’ is the tallest at 20-25 ft (6-7.6 m) with a 20-ft (6 m) width. ‘Ann’, below, which I photographed at the U.S. National Arboretum is the earliest-flowering; ‘Jane’ is latest; the rest are midseason.

‘Betty’ shows the upswept tepals of parent M. liliiflora. It is a rounded, multi-stemmed shrub.

‘Susan’ sports twisted tepals; it is slightly fragrant.

The abundant tepals of ‘Ricki’ with their white interior hint at its M. stellata parentage.

Finally, here’s ‘Jane’ towards the end of her flowering period; unlike the others, her open blossoms recall the form of her parent M. stellata ‘Waterlily’.

On an April 2008 trip to Ireland to find my grandfather’s ancestral home in the countryside near Banbridge (see my musical blog titled ‘Galway Bay’), we visted the National Botanic Garden, Glasnevin near Dublin where I found the magnificent Magnolia ‘Galaxy’ at on April 26, 2008. A late-flowering, tree-form magnolia with upward branching and a mature height of 30-40 ft (9-12 m), it is a 1963 cross between Magnolia liliiflora ‘Nigra’ and M. sprengeri ‘Diva’. Like the ‘Girl’ Series, it was developed at the U.S. National Arboretum in Washington DC in 1963 and released in 1980.

I love to visit Vancouver’s Van Dusen Botanical Gardens in spring; it’s where my mother and I would go to get our floral fix when I travelled ‘home’ from Toronto to visit her. There is so much to see there, I wrote a 2-part blog called ‘Spring at Van Dusen Botanical Garden’. One of the highlights is their magnolia collection, including Magnolia ‘Star Wars’, below, which I photographed on May 2, 2017. It was bred in New Zealand by Oswald Blumhardt, one of New Zealand’s renowned magnolia breeders. It’s a cross between Magnolia campbellii and M. liliiflora, bearing large, sweetly-scented flowers.

I photographed another New Zealand-bred magnolia at Van Dusen on May 2nd. This is ‘Apollo’, a Felix Jury cross between M. campbellii subsp. mollicomata ‘Lanarth’ and M. liliiflora ‘Nigra’. It is said to have a fruity fragrance but the flowers were too high for me to sniff.

And finally, on Van Dusen’s Rhododendron Walk on that same May day, I found a stunning specimen of evergreen Magnolia cavalerei var. platypetala from China (formerly Michelia). The fragrance was wonderful.

In 2019, I visited lovely Darts Hill Park Garden Park in South Surrey, outside Vancouver, B.C. It is the home of the late plantswoman Francisca Darts (1916-2012) whom I was lucky to meet with my mom, Mary Healy, at the right below, one rainy spring day long ago. I’m including this photo because my mother loved magnolias, she died the same year as Francisca, and she would be tickled pink to know that they are featured together under all these magnificent specimens.

During my 2019 visit to Darts Hill, I was interested to find Magnolia officinalis in flower, below. Discovered originally in Sechuan, China in 1869 by French Abbé Henry David (of Davidia fame), it was found again as a cultivated plant in flower in 1900 by British plant explorer Ernest Henry Wilson who collected seeds that autumn to send to his then-employers at Veitch Nursery. As he wrote later: “The Chinese designate this species the Hou-p’o tree, and its bark and flower-buds constitute a valued drug which is exported in quantity from central and western China to all parts of the Empire. It is for its bark and flowerbuds that the tree is cultivated. The removal of’ the bark causes the death of the tree and this would account for its disappearance from the forests. The bark when boiled yields an extract which is taken internally as a cure for coughs, colds and as a tonic and stimulant during the convalescence. A similar extract obtained from the flower-buds, which are called Yu-p’o is esteemed as a medicine for women.” Bark from the tree is used in Chinese medicine to this day.

I will finish this long wander through the hardy Magnolias with two recent arrivals, having been transferred there taxonomically from the former genus Michelia after genetic sequencing determined that Magnolioideae should contain only one genus. Included in that are 210 species of magnolias from around the world. I found Magnolia laevifolia, formerly Michelia yunnanensis, at the San Francisco Botanical Garden (then Strybing Arboretum) one March long ago.

And though it was a little too bright at the Los Angeles County Arboretum on January 28, 2018 for good photos, I was delighted to find fragrant Magnolia doltsopa ‘Silver Cloud’ (formerly Michelia) in flower.

As I gaze out the window in Toronto on this March day, winter is still holding on with a freshly-fallen blanket of heavy, wet snow. But spring is surely just around the corner – and with it, those spectacular floral peacocks, the magnolias.

**********

Anxious for spring, too? See my recent blogs on tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera), redbuds (Cercis canadensis and its cousins), and the many native northeast maples.