We could have hung out by the hotel pool sipping a cool drink and reading our mystery books. After all, a salt-rimmed margarita in the hot sun when it’s snowing hard at home is always a welcome respite in winter. But you don’t get to experience real Mexico by doing that. If, like me, you’re interested in nature and getting out of the tourist enclaves, if you want to see desert or jungle or mountains untouched by development, you have to have a plan. My plan while visiting the little town of Zihuatanejo on the Pacific coast north of Acapulco involved researching what was available nearby. This was our fourth visit to Villa Carolina, below, a small palapa hotel on Playa la Ropa in this former fishing village, a hippie town in the 1960s (seriously, Timothy Leary tried to create an LSD-fuelled communal living project here in 1963, but got shut down by Mexican authorities) that has become a favourite beach getaway not just for Americans and Canadians, but for Mexicans with vacation homes.

But the difference between our last visit in 2006 and winter 2023 is that a new ecological park had been developed not too many miles away and I was determined to pay a visit to El Refugio de Potosi. Which is how we ended up in the back seat of our guide Javier Pérez Sosa’s car at 8 am heading southeast through little towns on the highway.

I had told Javier in advance that I was interested in native flora and hummingbirds, so we parked beside the road in the countryside where I was surprised to see a wetland covered with water lettuce (Pistia striatotes). Though listed as an invasive most everywhere, no one really knows where it originated; various experts believe it to have been native to both Africa and South America, thus it is called “pantropical”.

What was most interesting was these native Mexican birds called northern jacanas (Jacana spinosa) that were wandering on top of the water lettuce, as you can see with the black adult and grey juvenile below. They’re perfectly adapted as waders with big feet to walk on floating plants, including water lilies, feeding on insects on the leaves or small fish below the surface.

We walked up a dusty driveway to an abandoned farm hut as Javier pointed out various birds in the trees around us. But he wanted to show me the green fruit of the cirian tree (Crescentia alata), also called the Mexican calabash, cannonball tree, jicaro, morrito or morro.

The hard fruit, once hollowed out, is sometimes used to make maracas or food and drink containers. It is believed that at one time megafauna were responsible for dispersal of the seeds; today the fruit is often broken open by horses which use their hooves to crush them in order to eat the seeds.

Back in the car and headed towards El Refugio, Javier slowed briefly and opened the back window so I could photograph a native roadside flower whose nickname, he said, means “hairbrush”. It is one of the Combretum genus endemic to Mexico, likely C. farinosum.

It wasn’t long before we arrived at the stone walls of the 7-hectare El Refugio de Potosi. Outside was a wonderful piece of art, a “Fish of Found Objects” made entirely of trash: beer cans, plastic plates, bleach bottles, toilet floats, compact disks, old toys, etc. As founder Laurel Patrick would tell me later about the fish, a community effort sponsored and financed by El Refugio: “We collected items from the road and the beach and others brought stuff they found or no longer use to create the sculpture. Obviously most of the donated items came from foreigners as the average local Mexican family does not have a surplus of unused or unneeded items. The goal is to use the Fish to start conversations about trash and littering. For many it was their very first opportunity to participate in such a project or to exercise even the most basic of design/art options.” (You can read here a 2013 story that relates how Laurel Patrick was inspired to create the refuge.)

Just inside the parking area, there were zebra longwing butterflies (Heliconius charithonia) nectaring on Ixora coccinea.

Nearby a geiger tree (Cordia sebestena) was in flower. Though most of the flora here is native, there are many beautiful tropical plants to catch the eye.

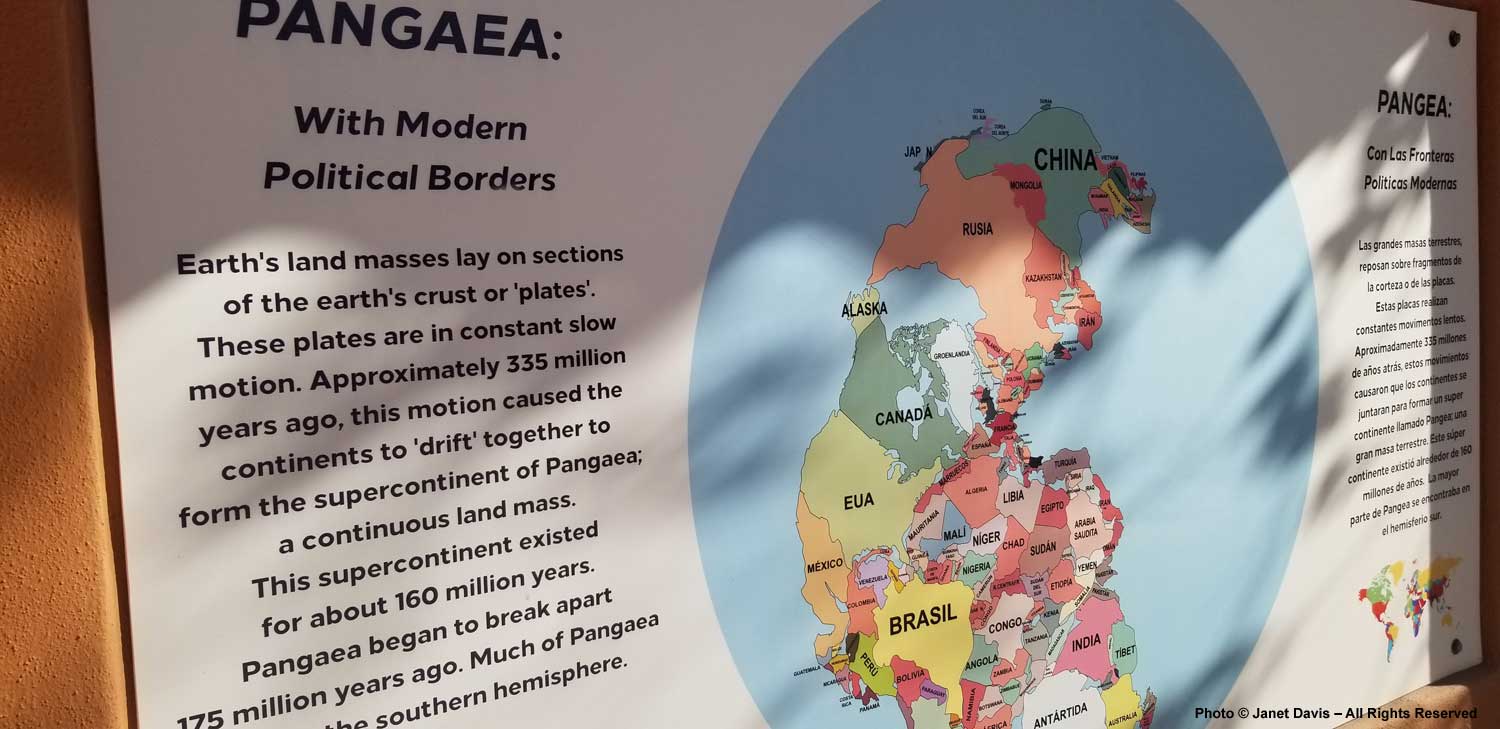

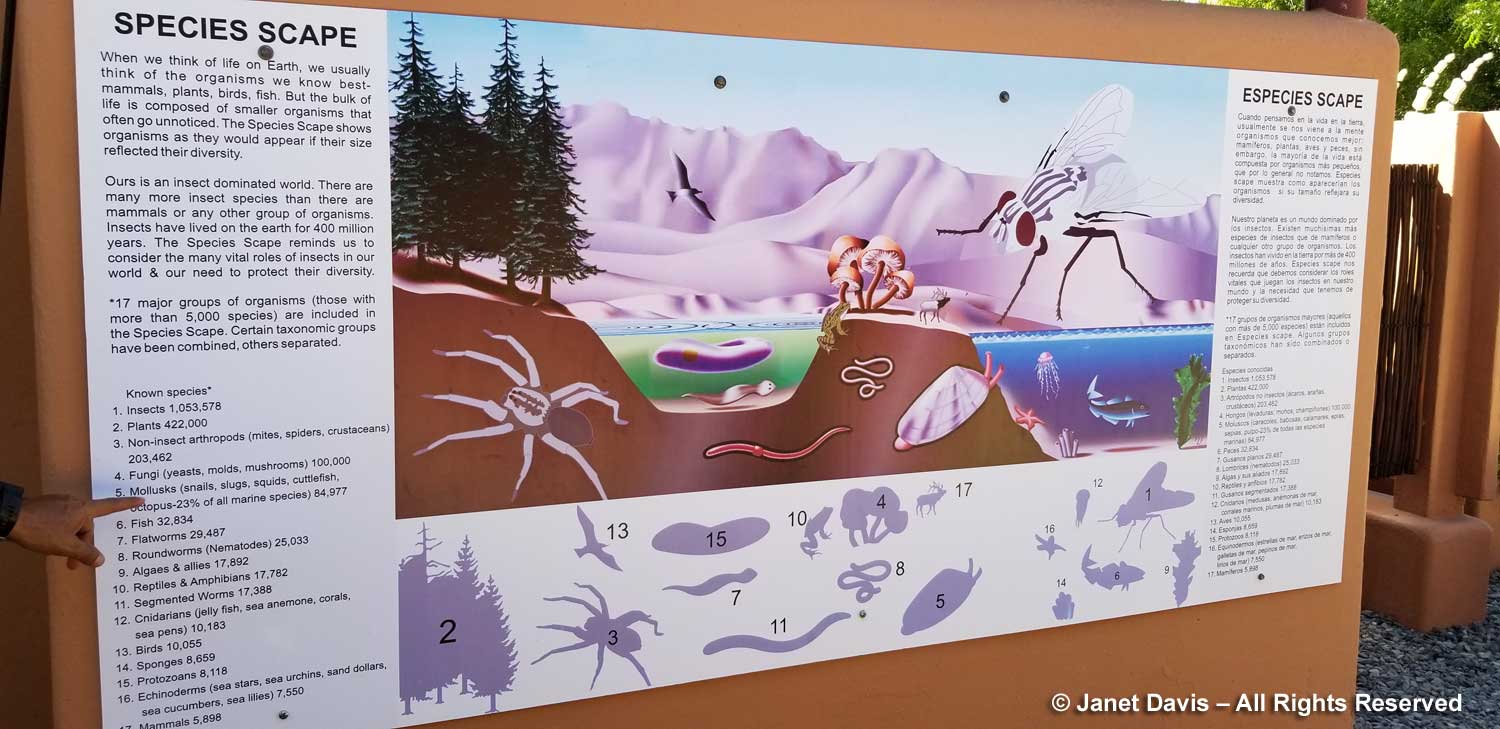

I also noted the first of many infographics we would see here. Understanding local ecology is one thing; grasping it in the context of deep time on the planet is what inspires visitors and reminds them that this is more than a wildlife refuge.

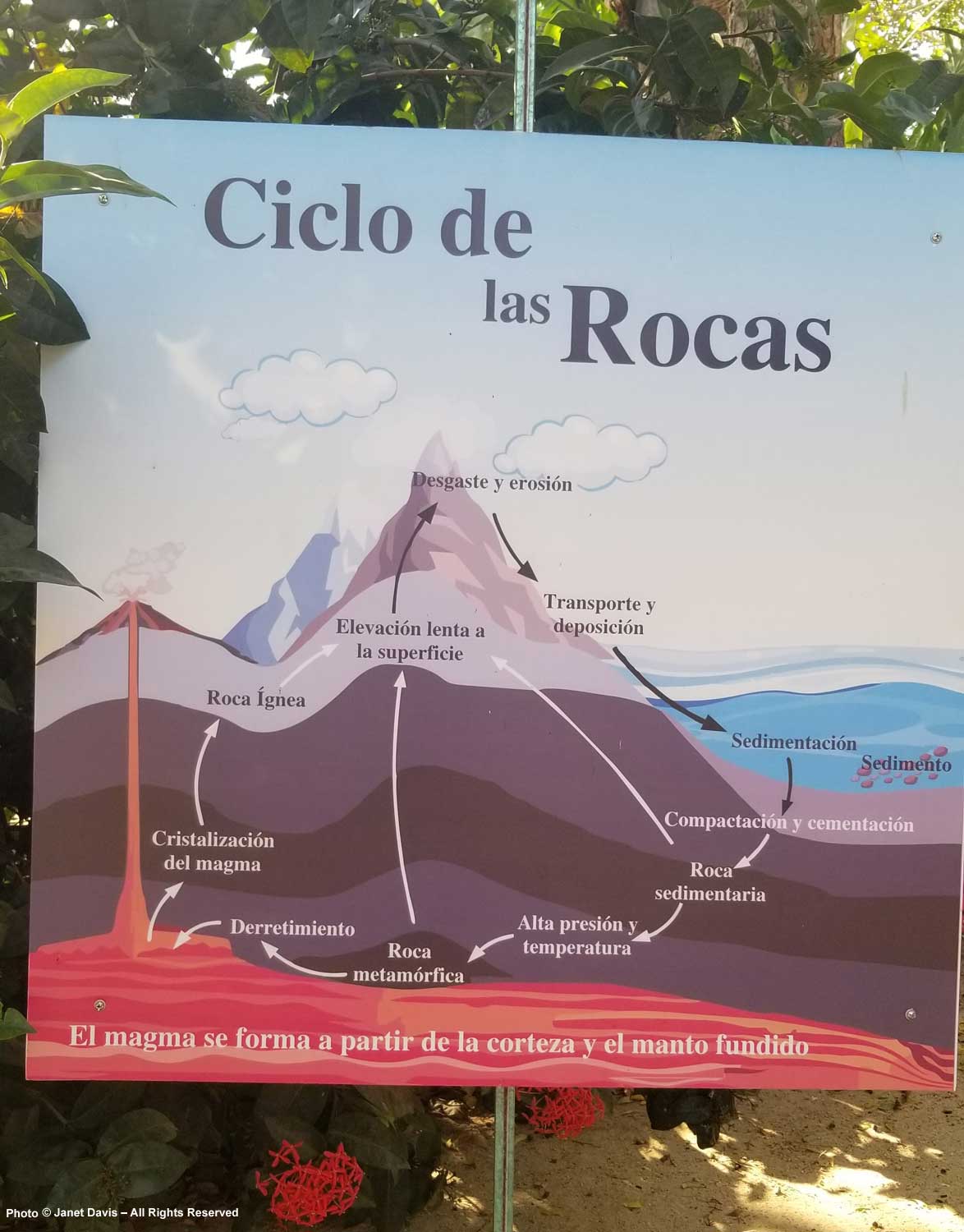

Then came the Ciclo de las Rocas. The rock cycle is not something every school student focuses on, but is the essence of geologic cycling on earth (and a natural component of climate change). Magma forms from earth’s molten crust and mantle; sometimes magma is extruded through volcanic openings and fissures (left) as lava that cools as extrusive igneous rock. Beneath the earth’s surface, metamorphic rock also melts as magma, later cooling and crystallizing as igneous rock. Tectonics slowly, over millions of years, thrusts the rock to the surface in the form of mountains. Weathering and erosion bring the rock and eventually entire mountain ranges back down as sediments (sand, mud, pebbles, etc.) which are carried into low basins and rivers, then into oceans. The sediments compact and cement together to become various layers or strata of sedimentary rock. Tectonics, i.e. subduction of one plate under another along coasts, eventually brings them underground where extreme heat and pressure change them once again into metamorphic rock which melts and is uplifted as part of mountain-building. This cycle has occurred everywhere on the planet over its 4.5 billion years.

Along the path, we came to a new little museum, the finishing touches still being applied.

Birds are shown….

….. along with their eggs, biggest to smallest.

Javier spent time stressing Mexico’s great biodiversity. The country, which occupies only 1.5% of earth’s surface, punches far above its weight in biodiversity, hosting 10% of the planet’s known species. It is in 3rd place globally in mammal diversity, 2nd place in reptiles, with insects representing the biggest share of Mexican fauna, almost 48,000 recorded species. When El Refugio’s owner Laurel Patrick first came to the region in the 1980s on winter vacation from Hood River, Oregon, where she owned a tree nursery, she became fascinated by the flora and fauna of the region but found few people who could talk to her about it. Conservation was virtually non-existent in the area. Eventually, she built a beach house near the small town of Barra de Potosi while partnering with biologist Pablo Mendizabal to create a non-profit center highlighting the wildlife and flora of the region. Finally, she made the decision to sell both her tree nursery and her beach house in order to fund and devote herself fully to El Refugio de Potosi. Construction began in 2008 and doors opened to the public in 2009. Three years later, she was named Conservationist of the Year by the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas.

We passed a boulder-edged pond filled with aquatic plants where the resident neotropical river otter (Lontra longicaudis) was swimming. He climbed up the rocky bank, gave my sneakers a quick sniff, then wandered off. El Refugio is both a wildlife refuge and research centre, so animals living here have either been rescued as rejected pets or as injured or orphaned animals. We would meet many others, like the otter, on our tour.

Orange-fronted parakeets (Aratinga canicularis) peered out at us from their cage. These birds, though not endangered, are often captured by illegal traders for the pet industry.

A beautiful, mosaic-tiled concrete armchair marked the hummingbird feeding station where dozens of feisty birds of a number of species were vying for a taste. Laurel Patrick made this under the tutelage of mosaic artist Sherri Warner Hunter.

Black-chinned hummingbirds perched daintily…..

…. while cinnamon hummingbirds flew between the feeders and nearby shrubs This is a male, indicated by the rufous feathers and the black tip on its red bill. I’ve included a video a little later in this blog showing the frenzy at the feeders.

The biome here is Coastal Tropical Dry Forest. The rainy season in the Zihuatanejo area is mostly June-October and the temperature is fairly consistent with daytime highs around 30-32C and night temperatures around 20-24C.

Infographics near the animal cages give a summary of their diet, habitat, litter size, diurnal/nocturnal nature and species stability.

We were able to meet the Mexican dwarf hairy porcupine (Coendu mexicanus) whose daytime nap we briefly interrupted.

A little further down the path were a coatimundi (Nasua narica) and collared peccary (Dicotyles tajacu), aka javelina, who live together peaceably.

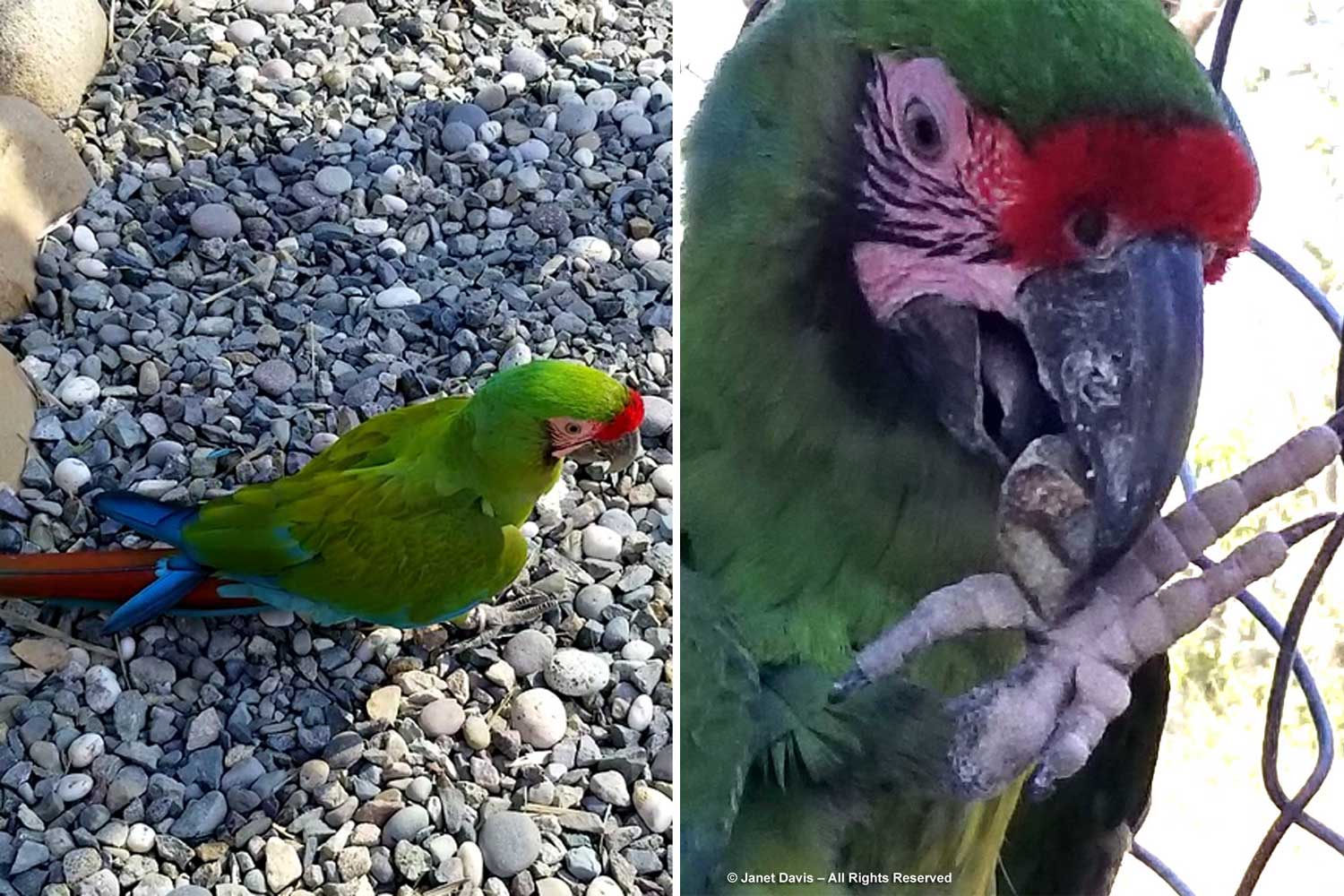

Most impressive of all the habitats at El Refugio is the large military macaw enclosure.

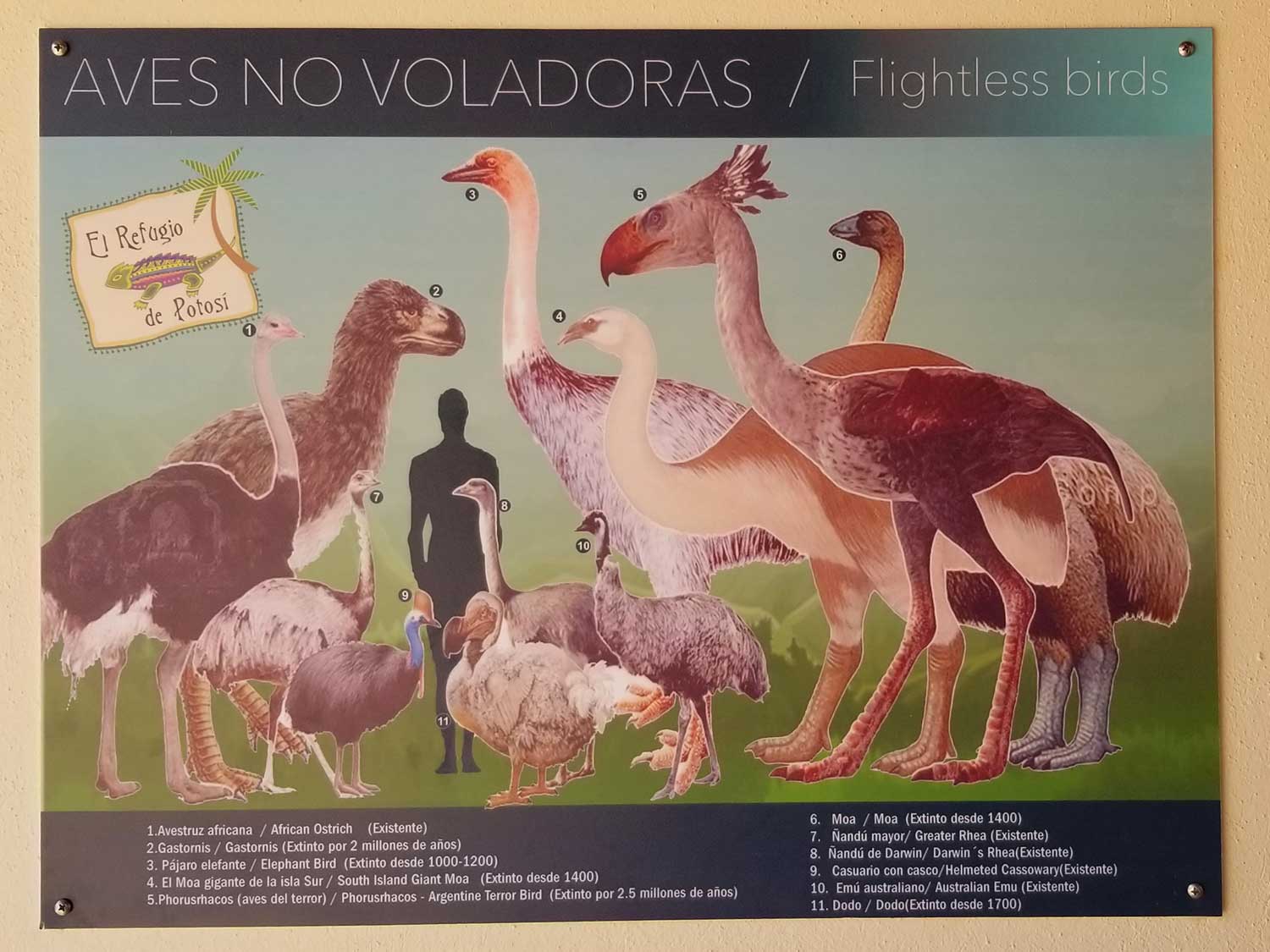

Outside was another interesting infographic, this one on the evolutionary status of flightless birds.

Nearest the door in the enclosure was a military macaw (Ara militaris mexicanus) on a termite nest. In the wild, macaws are known to make their own nests on these structures.

Says Laurel Patrick: “The military macaws are certainly endangered in the wild and once populated this area. The 14 macaws that reside here were either rescues or the result of a breeding pair that have sanctuary here. My dream is to train a group of the macaws to free fly towards scattered feeding stations during the day and return to a safety cage at night. Because they are birds that have been in captivity throughout life, they cannot just be released as they have zero survival skills. The project will require participation from the local communities as these birds are frequently poached and can be sold for a significant amount. There is still a strong market for wild birds to cage, even though it is strictly prohibited in Mexico.”

I was fascinated by the rock-gathering being done by the macaws. One seemed to be chewing on a fairly large stone, similar to my childhood budgie working on the cuttlebone in his cage.

Here’s that little video I promised earlier:

The iguana enclosure contained several large green iguanas (Iguana iguana) hiding in the striped leaves of a screw pine (Pandanus spp.) or noshing on chopped-up cabbage, but we were also treated to the sight of the less well-known spiny-tailed iguana (Ctenosaura pectinata), native to western Mexico.

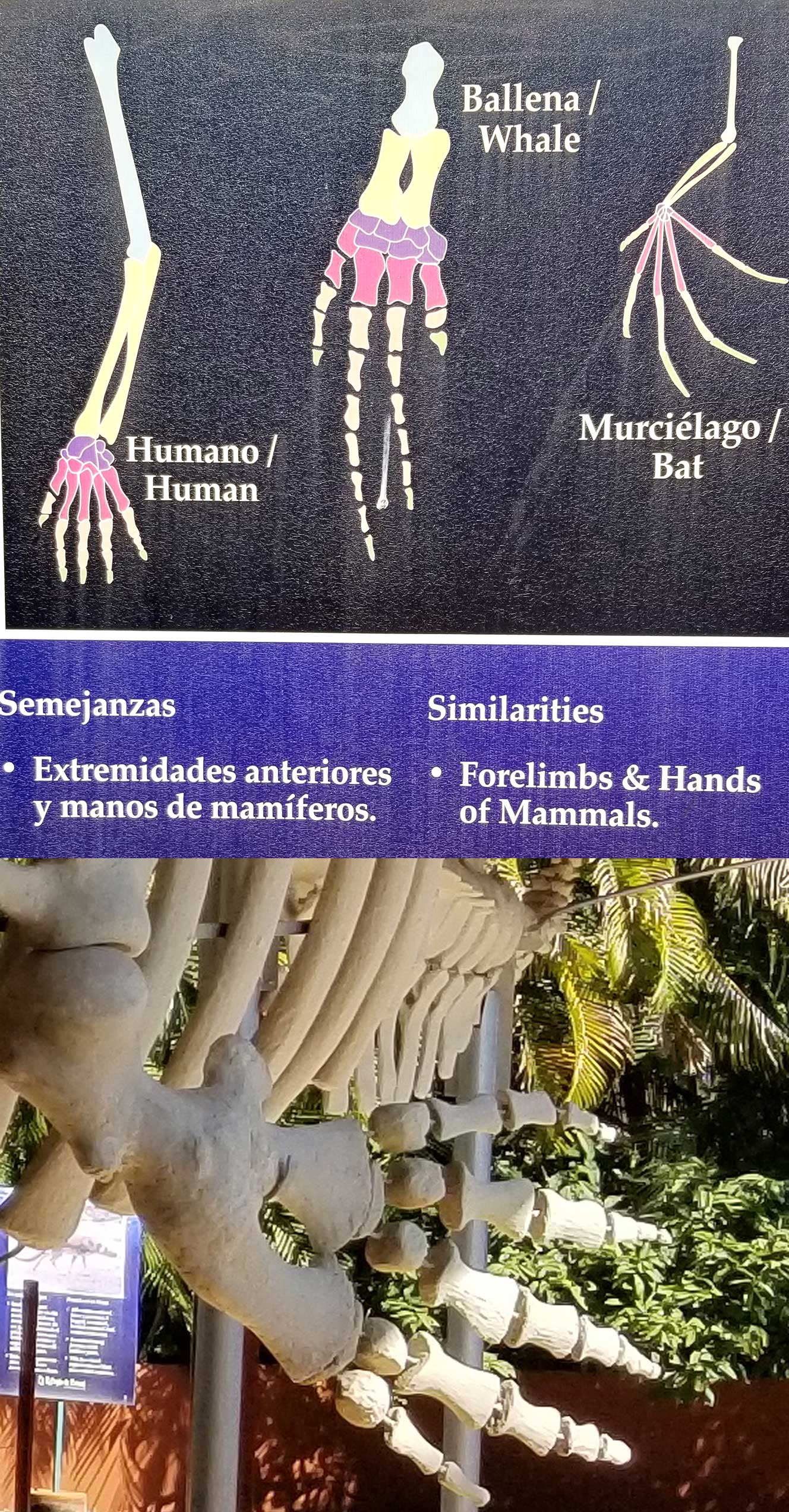

The biggest exhibit here is the 60-foot-long sperm whale skeleton (Physeter macrocephalus). The whale was found in 2009,washed up and decomposing on a beach nearby. Many local people helped to bring it to El Refugio where it was assembled and mounted. Sperm whales are the largest toothed predators in the world, but they are smaller than blue whales which can grow to more than 100 feet in length.

The finger-like bones in its flippers (toothed whales or odontocetes have five bones, untoothed whales or mysticetes like the blue whale, Baleena azul, have four) provide an excellent illustration of homologous limb structures, now adapted for different functions, but indicating that humans, whales and bats share a common ancestor.

Nearby, artist Daniel Brito was beginning work on a mural that would show the human evolutionary path out of water.

As Laurel explained, apart from the ancient horsetails (Equisetum), it will also include the ginkgo tree (G. biloba), with its deep evolutionary lineage.

This area featured another ancient plant, a cycad – sago palm (Cycas revoluta) – to help tell the evolutionary story, along with large native ferns.

More interpretive signage stressed the role of insects on earth, whose known species currently tally more than a million species – and likely a multiple of that number of insects not yet found or categorized.

I stopped to admire more tropical garden flowers, including hibiscus….

….. and golden dewdrops (Duranta erecta).

Javier pointed out the yellow flowers of nanche (Brysonima crassifolia), a native shrub whose small fruit is popular as a dessert and a liqueur.

We finished our visit with a climb to the top of the 60-foot-tall (18 m) observation tower. For Laurel, it was important to have a feature that gave people from the area, who perhaps have never travelled by plane or even been in a skyscraper, the opportunity to look over the landscape all the way to the horizon.

From the top, we could gaze over the rooftops of El Refugio’s buildings and nearby coconut plantations to the Pacific Ocean and the rocky, white islands called Los Morros de Potosi.

In the other direction, we could see the Sierra Madres and the nearby Laguna Carrizo. On its far shore, I saw a line of white which, when I changed to my little telephoto camera…

…. became hundreds of American white pelicans (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) along the shore, fishing in their Mexican winter home. The largest migratory bird, its breeding ground is in Canada and the northern U.S.

Our visit was over but it was lunchtime! We travelled to nearby Laguna de Potosi where open-sided beachfront cafes with covered roofs called “enramadas” were serving food. We let Javier pick his favourite.

I seldom order beer, but after several hours of touring in the heat, I was happy to sample Mexican Victoria beer….

…. followed by tasty fish tacos.

If my knees weren’t so tetchy, we might have taken a kayak out for a spin on the laguna! There is so much to see. Next time.

We took the coast road home to Zihuatanejo where the day ended with yet another beautiful Mexican sunset from Playa la Ropa.

IF YOU GO:

Check the El Refugio de Potosi website for visitor information.

Apart from public open hours on Saturday and Sunday mornings, there are three approved guides on this page who can visit by appointment at other times. I highly recommend Javier Pérez of Explora Ixtapa who can be reached via Whatsapp at 52-755-104-7392. (He also does bicycle tours.)

************

Do you love Mexico, too? You might enjoy reading my musical love letter to Mexico, part of a blog series I did a few years ago.