In my part of the world, winter often seems like a time that nature has forgotten. Frozen earth, dirty snow, leafless tree boughs except for the evergreens – a subdued landscape of grey, brown and white. Yet there is life teeming deep in the soil under that snow and spring beckons just months away. And there is majesty in the skeletal architecture of trees. While returning to Toronto from our cottage on Lake Muskoka one late afternoon recently (and, I hasten to add, I was in the passenger seat), I clicked my camera at tree vignettes flanking Highway 400, the major north-south route linking the city to cottage country and beyond. Forest, farm field, windbreak, granite outcrop… all stood out in moody relief against the January sky. Photographing at 70 miles an hour doesn’t give sharp results, but as a low-resolution mosaic, it’s a beautiful way to appreciate the winter landscape and the skeletons of trees.

With winter hanging on for five months or more in Toronto, the architecture of trees becomes an important consideration in garden design. Since I’m a bit of a tree geek, I pay attention to those things, and thought some of my blog readers might share my enjoyment. So here is a roster of hardy shrubs and trees with distinctive winter bark and branching, arranged by botanical name. It’s…um….quite comprehensive — let’s just call it an “encyclotreedia”. Or, given the date, perhaps we can call it a Valentine to Trees. And please note, this is not a recommendation list, merely a photo guide to many dediduous species, native and non-native, well-behaved or potentially invasive. Almost all were photographed in Toronto’s Mount Pleasant Cemetery, the 200-acre arboretum I am so very fortunate to have less than a mile-and-a-half from my home, a place in which I’ve been photographing flora for 20 years.

Acer davidii – Pere David’s Maple: This maple represents one of the hardiest of the beautiful snakebark maples. Its bark is olive-green with silvery vertical stripes intercut with small horizontal, green lenticels. In time, the bark changes to striped light-brown. A beautiful, small, multi-stemmed tree that grows to 30-40 feet (9-12 metres) or so and colours nicely in autumn. Sadly, the one I know has developed sun scald on its exposed flank, but seems to hang on despite the gaping splits in the trunk.

Acer griseum – Paperbark Maple: I grow this lovely, small, Asian maple in my own garden, regrettably out of my sight line in a side-yard where I cannot appreciate the gorgeous exfoliating bark on its slender red trunk, especially in winter against the snow. Paperbark maple matures somewhere between 20-30 feet (6-9 metres) with a lovely, vase-shaped form. Trifoliate leaves turn scarlet in fall.

Acer pseudoplatanus – Sycamore Maple: The Latin name of this large (75-90 feet, 23-27 metre), short-trunked Eurasian maple means “false plane tree”, and its leaves and exfoliating grey-brown bark do bear some resemblance to the American sycamore and Oriental plane tree of the genus Platanus. But like all maples, sycamore maple has opposite branching, unlike alternate-branched plane trees, and its fruit is a samara rather than the spherical “buttonball” fruit of plane trees. The confusion is heightened by the common name “sycamore”, applied to both the maple and American plane tree or sycamore which derives from the Greek word “sykomoros”, meaning fig-mulberry. But it is thought to refer to a large Middle Eastern fig called Ficus sycamorus, an ancient tree mentioned in the bible; thus the word later became generic for “shade tree”.

Acer rubrum – Red Maple: This native tree starts out with smooth, light-grey bark, as with the wonderful fall-colouring Acer rubrum ‘Morgan’, below…..

….. before developing its rough, scaly, dark bark later in life, when it can be as tall as 90 feet (27 metres) in wide-open areas, but likely already nearing the end of a life that averages 80 to 100 years.

Acer saccharinum – Silver Maple: We once had a tall, majestic silver maple on the boulevard in front of our house in Toronto, and I counted the rings when the city came to cut it down in 1996. There were 81, which meant it had been planted when our house was built, around 1915. Its bark and bearing at that age looked like the silver maple below: long, narrow strips of medium grey, many fallen off, and the main trunk dividing into sub-trunks before flaring into elegant limbs on high. I still miss it.

The upper bark of the silver maple is produced in sheet-like plates, something like the bark that the hairy woodpecker is attacking in my video made in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, below.

Acer saccharum – Sugar Maple: Who hasn’t stood under a sugar maple in autumn and gazed in awe at the sunset array of fall colours, below? It’s in winter when we notice the dark, furrowed, sometimes curling bark of the trunk leading up to the widespread crown, the massive canopy often missing brittle limbs in old age. And, of course, just below that furrowed bark is the xylem tissue that scarcely waits until winter’s last gasp before drawing up sweet sap from the thawing soil – sap that turns into delicious maple syrup in the right hands.

Sugar maple is the quintessential fall-colouring tree in eastern North America.

Aesculus flava – Yellow Buckeye: When young, yellow buckeye’s bark looks smooth and grey, like beech bark. As the tree ages to its mature 50-70 feet (15-21 metre) height, its bark develops scales and loose plates. The tree below developed sub-trunks a short distance from the base.

Aesculus hippocastanum – Horsechestnut: There isn’t much remarkable in the scaly, ridged bark of a mature horsechestnut trunk. What is spectacular is the oval crown and the branches that hang down from 100 feet (30 metres) or so, as if anticipating the weight of those big, beautiful, white flower panicles in June……

….. and, of course, the plump, sticky, terminal winter buds that look like they were shellacked, and can scarcely wait to burst open on the first warm days of spring.

Ailanthus altissima – Tree of heaven: This Chinese tree is such a successful weedy invader throughout North America, where it was once grown as a street tree, its clones, suckers and self-seeded saplings pop up in cracks in the pavement and untended lots everywhere. It is more likely to be described as “tree of hell” than its normal common name. Fast-growing, it matures at 60-80 feet (18-24 metres), its bark green and smooth on young trees, but grey with rough furrows on older trees. Tree of heaven gained notoriety in 1943 when it was featured as the central metaphor in the Betty Smith novel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.

Alnus incana – European grey alder: Look up from the smooth, lenticel-engraved bark of grey alder in winter, and you’ll see the remnants of last summer: the little black, seed-bearing, female cones. Grey alder grows naturally in damp soil, but is also tolerant of dry soil. It can reach 50 feet (15 metres).

Betula alleghaniensis – Yellow birch: If you see yellow birch in winter with its shiny, peeling bark and horizontal lenticels , you’re forgiven for thinking you’ve stumbled upon a beautiful cherry. For that’s what a young yellow birch resembles. It grows to 75 feet (23 metres) in ideal conditions.

Betula ermanii – Erman’s birch: Though quite variable in appearance, Erman’s birch or Russian rock birch can have creamy-white bark like paper birch or resemble native river birch, in that older trees develop peeling, shredded bark in brown, gray, orange and white. Often multi-stemmed, Erman’s birch matures at around 60 feet (18 metres).

Betula lenta – Cherry birch, Sweet birch: I love this native birch, which should be grown much more than it is. The wood is used for furniture and flooring. The bark starts as a reddish-brown, turns dark gray, then develops thin scales as it ages. It grows to 50-60 feet (15-18 metres) in favorable conditions.

In autumn, cherry birch with its apricot orange leaves is an exquisite part of the fall color parade.

Betula nigra – River birch: As the name suggests, this is a tree for damp places, but not small places. When happy, it can reach 70 feet (21 metres), often multi-stemmed, its bark flaked with a patchwork of cream, buff, apricot and brown papery scales.

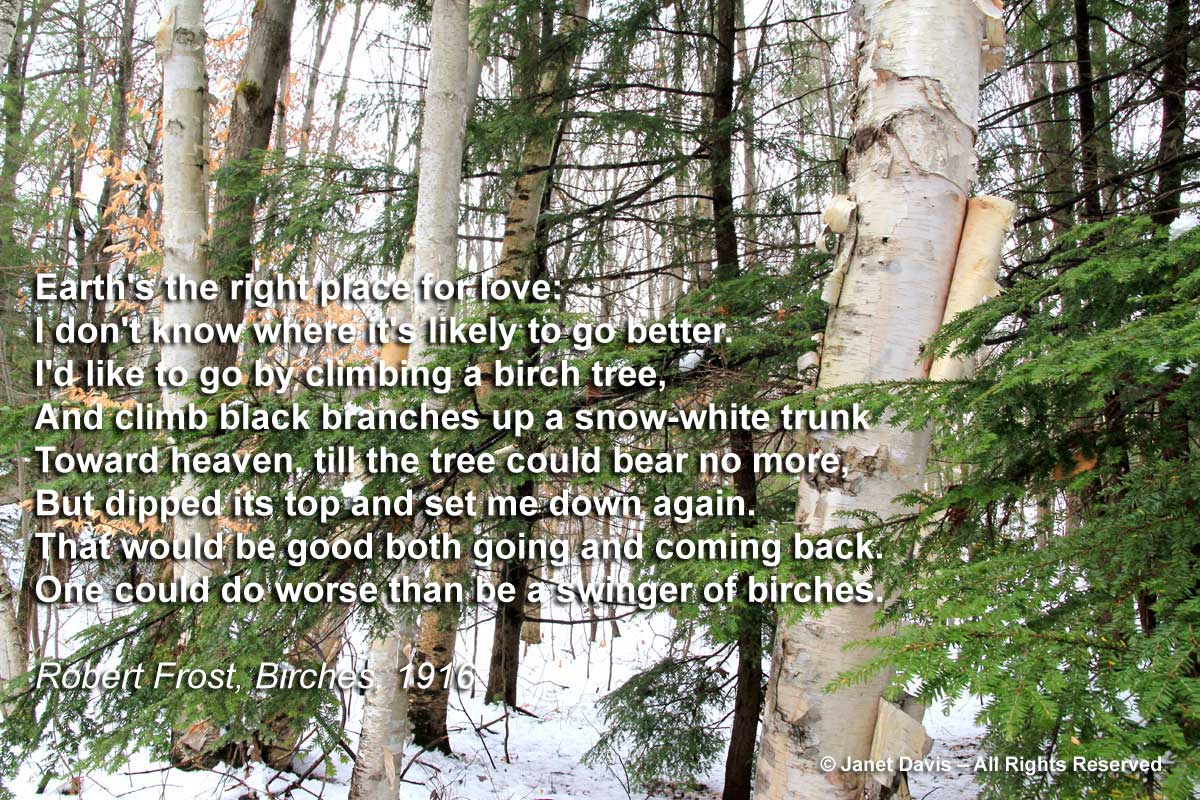

Betula papyrifera – Paper birch: Don’t we all have a special place in our hearts for the paper birch? Even with its insect enemies – the bronze birch borer, birch leafminer – don’t we all think romantically of Robert Frost’s Birches? That shimmering white bark, the black hawk-eyes winking from the trunk, the leaves fluttering like tiny golden flags in autumn.

Paper birch grows to 70 feet (21 metres), often multi-stemmed; its brown park with pale lenticels eventually turns white. Indeed, as Robert Frost once wrote, one could do much worse than be a swinger of birches, like the ones shown growing with hemlocks on the road behind my Lake Muskoka cottage.

Betula utilis var. jacquemontii – White-barked Himalayan birch: Many experts consider this to be a finer landscape alternative than our native paper birch. Selected forms have shimmering-white bark on a slender, often multi-stemmed tree that reaches 30-40 feet (9-12 metres). Sadly, it is also susceptible in time to the bronze birch borer.

Carpinus caroliniana – Blue beech, American hornbeam: This lovely little understory tree is at least as wide as it is tall (20-30 feet, 6-9 metres), with muscled grey bark (another of its common names is ‘musclewood’) and a fluted trunk. It’s one of my favourite northeastern natives, with delicate, birch-like leaves that turn orange in fall.

Carya cordiformis – Bitternut hickory: When young, this tree’s bark is smooth and grey; as it matures to a height of 100 feet (30 metres) or more, the bark develops wavy ridges and regular vertical furrows. Bitternut hickory lives about 200 years and its durable wood is used for furniture.

Carya ovata – Shagbark hickory: One of my favourite trunks to photograph, so illustrative of its common name. As a young tree, this hickory’s bark is grey and smooth; as it matures to over 120 feet (36 metres) in height metres), the bark breaks into long, vertical plates which adhere to the bole in the middle while the ends curve away and produce the ‘shaggy’ look. It is long-lived, to 300 years or more and produces edible nuts.

Castanea dentata – American chestnut: There are precious few of these iconic trees left in North America, but Mount Pleasant Cemetery has a number of small specimens, their sawn upper limbs a clue to the introduced chestnut blight that decimated the North American population in the early 20th century. A Carolinian species native to the northern shore of Lake Erie, it once grew to lofty heights of over 100 feet (30 metres), but is now seen in the wild as small sprout trees from dead stumps. The trunk on the smallish tree below with its interlaced furrows and ridges indicates its old age; young bark is smooth and chestnut-brown.

Castanea mollissima – Chinese chestnut: A small-medium sized tree growing to about 40 feet (12 metres) with an open canopy and wide-spreading branches, Chinese chestnut is resistant to the chestnut blight that kills American chestnut. Like the tree below with its brown, ridged bark, foliage is marcescent, with leaves often persisting on the tree throughout winter. It produces edible nuts (though not the delicacies of the sweet Spanish chestnut) and is currently the subject of experiments to produce a viable hybrid with the American chestnut.

Catalpa speciosa – Northern catalpa: Of all the sylva of the American forest, Northern catalpa is the most tropical in appearance, with purple-splotched white flowers held in big panicles.. Though native to a relatively small swath from Kansas south to Texas and east to Louisiana, it is a remarkably hardy tree and thrives in Toronto (USDA Zone 5, like Chicago). It’s bark is grey-brown with shallow fissures and its crown is irregular with masses of crooked branches that give it a witchy appearance. However, certain trees, interestingly, develop a tall, narrower profile than the one below.

Celtis occidentalis – Hackberry: This is one of those nondescript, native trees (to 60 feet – 18 metres) that nonetheless proves its worth as a pollution-tolerant choice for city streets. Its bark is smooth and greyish when young, but as it matures it develops corky wart-like bumps that form wavy, vertical ridges.

Cercidiphyllum japonicum – Katsura: This most elegant of Asian trees has bark that starts out smooth, but later splits into thin, papery strips as it grows (often multi-stemmed) to a height of 30-40 feet (9-12 metres) or more. Its senescing, heart-shaped leaves produce maltose, which in the right conditions produces a burnt sugar aroma as one walks near them in autumn.

Katsura is a dioecious species, meaning there are male and female trees. In winter, the remnants of last summer’s fruit pods often decorate the canopy of a female katsura tree.

Cladrastis kentukea – Yellowwood : This is a favourite tree of mine when it deigns to flower in late spring or early summer with masses of pendulous, wisteria-like, white flower clusters (below) – an auspicious event that happens once every 3 or 4 years, if you’re lucky! It’s native to the southern U.S. but hardy here in Toronto, though subject to sunscald in winter. Bark is smooth, grey and beech-like on a small-medium tree reaching 30-50 feet (10-15 metres).

The spectacular, cascading flowers of the yellowwood aren’t produced every year, but they are a beautiful sight when they are, as here in Toronto’s Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

Cornus mas – Cornelian cherry: One of my favourite shrubs or small trees, quite likely because its bright-yellow umbel flowers are among the very first to bloom in late winter or early spring. This dogwood, native to Europe and western Asia, reaches 20 feet (9 metres) tall and almost as wide, and has the prettiest mottled tan-and-cream bark on its slender trunk(s).

Cornus sanguinea – Common European dogwood – There are shrubs, of course, that boast brilliant winter bark, and none is more beautiful than the selections of European dogwood that celebrate the cold ‘midwinter’. This is ‘Midwinter Beauty’, below, but ‘Midwinter Fire’ is just as brilliant, with blazing sunset colours against a snowy landscape. Be sure to cut back your Cornus sanguinea in early spring in order to guarantee bright stem colour from the new growth in the following winter.

Cornus sericea – Red-osier dogwood: Though it might be common and a little old hat by now, the red canes of the new growth of ultra-hardy red-osier dogwood are always luminous in the winter garden. But do remember that you need to cut back the older canes in late winter or early spring, in order to encourage the bright-red colour of the new ones for the following winter.

Cornus sericea ‘Flavamirea’ – Yellow-twig dogwood: I love the golden canes of yellow-twig dogwood in winter; they add a little pool of sunlight to an otherwise barren spot. Left unpruned, this dogwood can reach 8 feet (2.4 metres), but as with red-osier dogwood, its brilliant colour is produced on new growth, so an annual cutting-back in late winter or early spring is necessary to ensure a good show.

And in case you’re wondering what to plant beneath those lovely golden stems, how about a sea of blue-flowered Siberian squill (Scilla siberica)?

Corylus colurna – Turkish filbert or hazel: A refined, pyramidal shape, relatively small stature (around 45 feet or 14 metres tall in colder regions) and problem-free demeanor often result in this tree being recommended for use in small gardens. It produces small, edible, but non-commercial nuts; however, its hardiness makes it a good rootstock for orchard species of filbert and hazel. In winter, below, the light brown, corky, flaking trunk and bark are quite attractive.

Fagus grandifolia – American beech: This beloved, stately native of our northeast forests is under attack from beech bark fungal disease, which is vectored by an introduced European scale insect feeding on sap and ultimately leads to formation of a canker that causes severe die-back. I cannot imagine what the deep woods behind our cottage on Lake Muskoka would look like without the muscled, grey bark and stout trunk of the American beech, below.

Fagus sylvatica – European beech: – A beautiful tree with a commanding presence, up to 90 feet (27 metres) tall, and many cultivars that feature pyramidal or weeping shape and colourful leaves. Sadly, the same beech bark disease (BBD) as occurs on native beeches is also claiming mature European beeches, like the magnificent copper beech (Fagus sylvatica ‘Cuprea’) shown below.

Fraxinus pensylvanica – Green ash: If there are any healthy native ashes left standing in North America after the reign of terror of the emerald ash borer, their trunks will look something like the one below, with its grey, ridged, corky bark. (Speaking personally, we lost our ash to EAB a few years ago, and most other ashes in Toronto will be removed in time.)

Ginkgo biloba – Maidenhair tree: As distinctive as the fan-shaped leaves of this stately deciduous conifer are – and luscious yellow in autumn – the brown bark is also attractive, with deep furrows and raised ridges. In winter, you can look up into the crown of a ginkgo and see the short spurs bearing the axial winter buds lining the bare branches.

Gleditsia triacanthos var. inermis – Thornless Honey locust: I am told that if you look carefully at the branching of a thornless honey locust, you’ll see a distinctive zigzag pattern to the growth of the twigs. The bark on young trees is a smooth olive-brown; as the tree ages, it becomes grey, fissured and flaky, often revealing the red under-bark. This form has a lack of vicious thorns, which distinguishes it from the main species. The elegant canopy created by the fine-textured foliage of honey locust has resulted in it being selected for cultivars like ‘Shademaster’, ‘Moraine’ and ‘Sunburst’. Sadly, honey locusts are subject to disease and insect pests. And despite being called “honey locust”, they’re not much visited by bees; the name actually derived from the sweet pulp within the seedpods.

Gymnocladus dioicus – Kentucky coffeetree – The Latin name Gymnocladus means “naked branch”, and describes the tree’s propensity for leafing out late and dropping its leaves early in autumn, thus leaving naked branches for most of the year. “Dioicus” describes its reproductive strategy, dioecy, meaning male and female flowers are borne on separate trees. On the ‘species at risk’ list in Ontario, Kentucky coffeetree once grew abundantly in southwest Ontario at the northern limit of its native range. But trees in Toronto do very well, and male trees (more desirable because of the huge, rattling seedpods of female trees) are available in the city’s Urban Forestry boulevard tree-planting program. The scaly bark is grey-brown and fissured on trees that reach 50-80 feet (24 metres) at maturity.

Those lush Kentucky coffeetree leaves, incidentally, are doubly compound or ‘bipinnately compound’ – and the largest leaves of any deciduous North American tree. Their intricacy makes the canopy spectacularly beautiful in summer, below.

Juglans cinerea – Butternut: We once had a tall butternut tree in the back of our garden. It produced ridged, oval, sticky green fruits that the squirrels ate, leaving husks all over the lawn (like black walnut, below). My husband loved a particular curved branch that extended across our garden, and I loved its history as a dye plant for the brown uniforms of the Confederate Army (the soldiers were nicknamed “butternuts”). Sadly, in the 1990s, it developed the butternut canker that would ultimately kill it – and has caused its population to decline throughout North America. I’m delighted that the tree below still survives in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, its trunk layered with grey-brown, diamond-ridged bark.

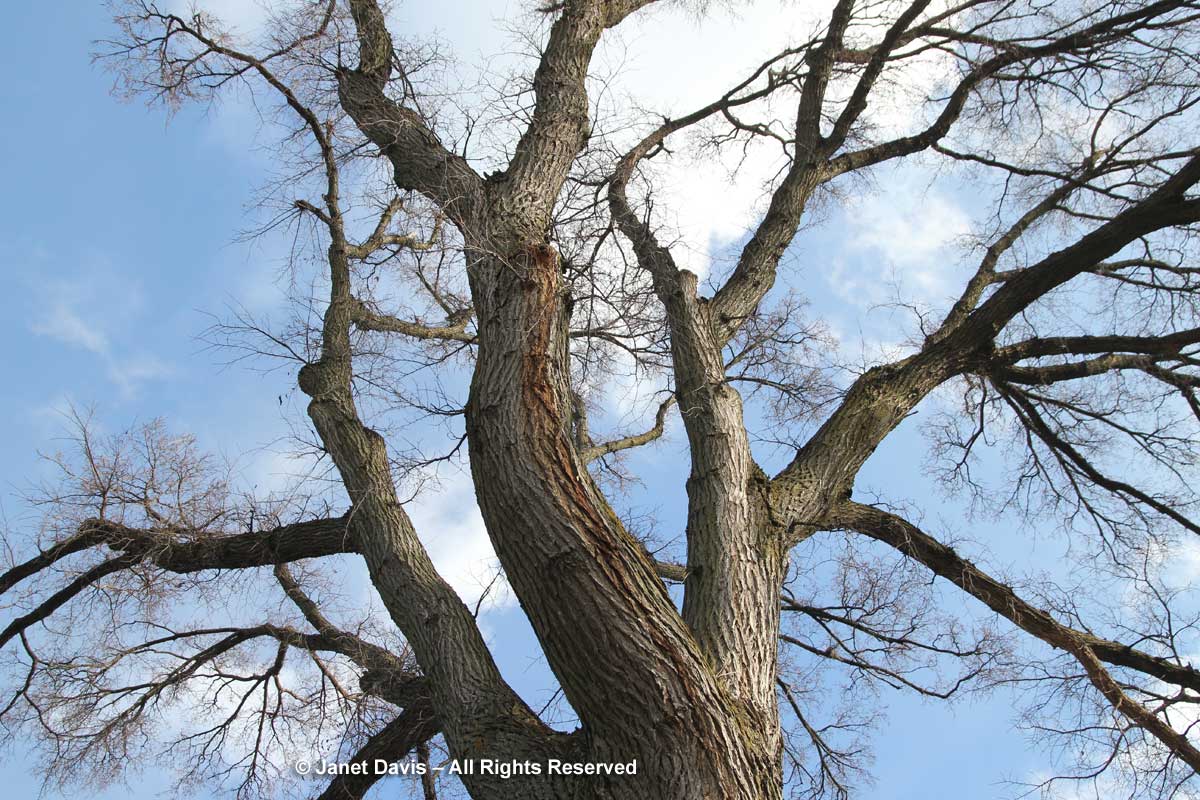

Juglans nigra – Black walnut: I live right under a huge black walnut, below – or perhaps I should call it a raccoon home…..Though the big green walnuts drive me crazy in the fall as they rain down on my roof like billiard balls, and the tree frightens me on a night like the one earlier this week, when an ice storm coated all the limbs, I do adore its graceful canopy and the cardinals that sing in its branches just above my bedroom ceiling. But my next-door neighbour and I have spent a fortune on arborists over the decades to cable its limbs and restrain its exuberance, while still providing lots of growth points.

Black walnut has a sturdy trunk with bark that’s braided with diamond-patterned furrows. From the time the United States was colonized in the early 1600s, black walnut wood was recognized as superior, and used for cabinet-making and gunstocks. The tree can reach 100 feet (30 metres) in moist, deep soil, and ensures its place in the natural forest by secreting juglone from its roots, bark, shoots and leaves. The botanical name for this is allelopathy, but many natural understory shade plants are unaffected by juglone.

And… because I’m not really happy with my winter photos of black walnut, here’s a summer shot illustrating that elegant canopy. Isn’t this spectacular?

Larix kaempferi – Japanese larch: The larches, like dawn redwood and bald cypress, are deciduous conifers that shed their needle-like leaves in autumn. They perform well in damp soil (the one below is growing in the run-off of a water feature) and turn yellow in autumn. Japanese larch can grow to 80 feet at maturity, its trunk reaching 3-4 feet (90-120 cm) in diameter. A young tree like this one still has its smooth grey-brown bark; in time, it will form plate-like strips that peel off to reveal the red underbark.

Larix laricina – Eastern tamarack: Though it prefers the cool, wet ground of sphagnum bogs or muskeg in the north country (it grows the furthest north of any tree in North America), the tamarack can be grown in adequately moist soil in a garden, too. Reaching 20-35 feet (6-15 metres) in height, it can be recognized by its slender profile, feathery leaves that turn brilliant-gold in autumn and dark cones that remain on the tree for years. Its dark grey-brown bark is thin and scaly. And, as one observer says: “In winter, it is the deadest-looking vegetation on the globe.”

Liquidambar styraciflua – Sweetgum: Perhaps if I lived in Virginia or North Carolina or Alabama where indigenous sweetgum trees grow in abandoned fields, I might have a more jaded view of this tall, majestic native southerner. But I have long adored the tall sweetgum that towers majestically over the stone angel in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, especially in autumn when the star-shaped leaves take on yellow, amber, scarlet and crimson hues and the “gum balls” dangle from the canopy. (See photo below.) Sweetgum grows 60-75 feet (18-23 metres) tall and 40-55 feet (12-17 metres) wide. Back in the pioneer days, the resinous gum exuded by the tree was used as chewing gum; it was also given to Civil War soldiers to treat dysentery. Though sweetgum isn’t native to Canada, we certainly saw a lot of gumwood trim used in Toronto houses at one time – including one I owned. If I were young, I would plant a small liquidambar in my garden; in the meantime, I’ll enjoy standing under that sweetgum in the cemetery.

My favourite sweetgum watches over this stone angel in Mount Pleasant Cemetery. This is how it looks in autumn.

Liriodendron tulipifera – Tuliptree, Yellow poplar: The tallest eastern hardwood, tuliptree can grow as high as 160 feet (50 metres) in the rich forests of the Southern Piedmont in Virginia and Georgia. In its stands in Norfolk County in southern Ontario near Lake Erie, at the northern limit of its native range, it tends to reach a more modest height at maturity. Its bark is furrowed and brown with intersecting ridges. In the wild its trunk can remain limbless for up to 50 feet (15 metres) before branching out. Below is the winter bark of a lovely variegated cultivar called ‘Majestic Beauty’.

Liriodendron flowers are exquisite, like yellow chalices (i.e. tulips) flamed with orange, and very attractive to bees. (In fact, the main nectar flow for an Atlanta beekeeper I’ve interviewed is April, when it flowers in the Georgia forests.)

Malus ‘Dolgo’ – Crabapple: Crabapples aren’t known for their attractive bark, but the “patchwork quilt” effect on the trunk of many crabs is often enough to aid in their identification in winter. This is old-fashioned ‘Dolgo’; its large fruit make it one of the best selections for crabapple jelly.

Malus tschonoskii – Pillar apple, Chonosuki crab: Here’s an unusual small tree, native to Japan, quite rare in cultivation and one that is often mistaken for a cherry in winter, because of its prunus-like bark. (In fact, pillar apple was once considered to be a pear, and placed in the Pyrus genus.) Narrowly upright to around 30 feet (9 metres), it puts on a beautiful show in autumn, when the multi-colored red, orange and gold foliage is arrayed against the tree’s smooth, grey limbs.

Metasequoia glyptostroboides – Dawn redwood: An iconic “fossil tree”, once thought extinct, until a remarkable series of events featuring its modern discovery in the 1940s in the mountains of Hubei, China, and the detective work of Chinese botanists who were able to connect it to an ancient fossil studied by a Japanese paleobotanist a few years earlier. Though I decided to focus this winter bark blog on deciduous trees, who cannot appreciate the amazing, fibrous, peeling, red-and-brown bark and perfect, conical form of the dawn redwood? And since, like the gingko, it’s a ‘deciduous conifer’, it met half the criteria in any case. Dawn redwood can reach at least 100 feet (30 metres) in perfect conditions, which in China include shady, moist sites near water, especially ravines and creek banks.

Morus rubra – Red mulberry: This Eastern North America native with its brown, furrowed bark and spreading crown is often confused with the Asian white mulberry (M. alba), which was imported from China to create a silk-spinning industry and later became an invasive in many regions. Although Donald Culross Peattie wrote that Choctaw women made a shawl from red mulberry inner bark, the native tree did not find favour with silkworms. But red mulberry’s blackberry-like fruit does find favour with birds and small animals, not to mention foragers who use it in jams, pies and cordials.

Ostrya virginiana – Eastern ironwood, American hophornbeam: Donald Culross Peattie writes of this small, native, understory tree in his wonderful A Natural History of Trees of Central and Eastern North America: “In our rich sylva, a little tree like the Ironwood melts into the summer greenery, or the silver intricacy of naked twigs in the winter months, in a way that makes it difficult to pick out and identify……. Everything about this little tree is at once serviceable and self-effacing. Such members of any society are easily overlooked, but well worth knowing.” In the winter, it’s the bark of the trunk that’s most noticeable: greyish brown, with fine, flaked scales, covering wood that is the second hardest (after Cornus florida) of all native trees. In the canopy, like little damselflies suspended from the branches, are the old catkins, flying alongside the odd old leaf, dainty reminders of the summer past.

Parrotia persica – Persian ironwood: There is one, lonely Persian parrotia in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, and it is a sweet little thing. A witch hazel relative native to Iran and the Caucasus, it has leathery leaves that turn myriad shades of gold, orange and crimson in autumn – but not in a fireworks way (in Toronto at least), more ‘a few here and a few there’. Growing to 40 feet (12 metres) with a dense, spreading crown, it features attractive, smooth, mottled bark, but branching starts so low on the tree, it’s a challenge to make a good photo of the trunk.

Phellodendron amurense – Amur cork tree: I am very fond of this small Asian tree (30-45 feet, 9-14 metres). It bears lovely compound foliage that turns a soft-yellow in autumn, clusters of deep-blue fruit (beloved by robins) and interesting, ridged, corky bark. It’s most happy in moist, rich soil, but will tolerate some drought. Dioecious, the female trees have proven invasive in certain warmer regions in North America.

Platanus x acerifolia – London plane tree: There is no mistaking this handsome tree, a hybrid of the Oriental plane tree (P. orientalis) and the American sycamore (P. occidentalis). Its smooth, mottled cream-olive-brown exfoliating bark graces a stocky trunk and branches on a tree that can reach 80 feet (24 metres) in height and almost as much in spread. Much more pollution-tolerant than its American parent (below), London plane trees grace city avenues throughout the temperate world.

Here’s a closeup of the gorgeous mottled bark of London plane tree.

Platanus occidentalis – American sycamore: This beloved native American tree, one of the parents of London plane tree, above, grows in a few spots in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, at the northern limit of its hardiness. On older trees, the trunk loses its mottled appearance and develops tight, geometric scales, but the limbs still show the exfoliating, leopardskin colouration. Sycamores – the largest deciduous trees in North America – are the stuff of legend in the eastern United States, especially in the bottomlands of the Ohio Valley, where they once grew to heights of 160 feet (49 metres) with trunks 13 feet (4 metres) in diameter. Their distinctive, hanging ‘buttonball” fruit is a tight, spherical aggregation of achenes – seeds fixed with little bit of fluff to aid them on the wind.

Populus alba – White poplar: Native to Europe, Asia and North Africa, this large poplar was introduced into North America in 1748 and has been so successful at propagating itself that it is now on the pernicious weed list of many regions. It grows 50-75 feet tall (15-23 metres) or more. The big trunk on old trees is dark-grey, but the upper branches are snow-white and very beautiful, especially with the silvery backs of the blue-green, maple-like, summer leaves fluttering in the wind.

Prunus maackii – Amur cherry: I love this rugged little cherry with its lustrous, curling, coppery-brown bark on young trees. Native to Manchuria and southeadt Russia, it was discovered by Russian naturalist Richard Maak in 1855 on the banks of the Amur River. Its extreme hardiness (USDA Zone 3) destined it for use as a street tree in prairie cities. It normally reaches 15-25 feet (4.6-6 metres) in height and width, but can grow taller in ideal conditions – which means the moist soil of the summer monsoon region of China.

Here is Amur cherry in May when the white chokecherry flower clusters are in bloom, below. This is in a small courtyard at Toronto Botanical Garden, where they have cleverly underplanted it with bugleweed (Ajuga).

Prunus serrula – Tibetan cherry, also called birchbark and paperbark cherry, makes quite a splash with its shiny, coppery-red trunk on a small tree that reaches 20-30 feet (6 -8 metres). Its foliage is narrow and willow-like, and it bars down-facing clusters of unremarkable, single, white flowers in early spring. Strangely, although it’s purported to be hardy to USDA Zone 5, I’ve never seen it in the east, either in Canada or the U.S. (though there’s supposed to be on in the Rock Garden at New York Botanical Garden).

Prunus serrulata – Japanese cherry: Perhaps no other bark is as well-known and beloved as the shiny, smooth, lenticel-etched bark of the myriad Japanese cherry trees. This is because the trees (called sakura in Japan) are part of an annual Japanese spring tradition called hanami, or cherry blossom festival. Below is the bark of ‘Shogetsu’, a late-blooming, pale pink, double-flowered Japanese cherry.

Pterocarya fraxinifolia – Caucasian wingnut: I’ve only seen this broad, majestic, walnut relative in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, where it dangles its 12-inch (30 cm) green fruit chains like long, emerald earrings from amongst the lush, pinnate foliage. Native to Iran and Central Asia, Caucasian wingnut is fast-growing to 80 feet (24 metres) tall with a 60 foot (16 metres) spread. Often multi-trunked, the bark is grey-brown, with long, ridged furrows. As in the photo below, the low branching and massive weight of the limbs often necessitates cabling.

Here are those amazing green fruits of the Caucasian wingnut.

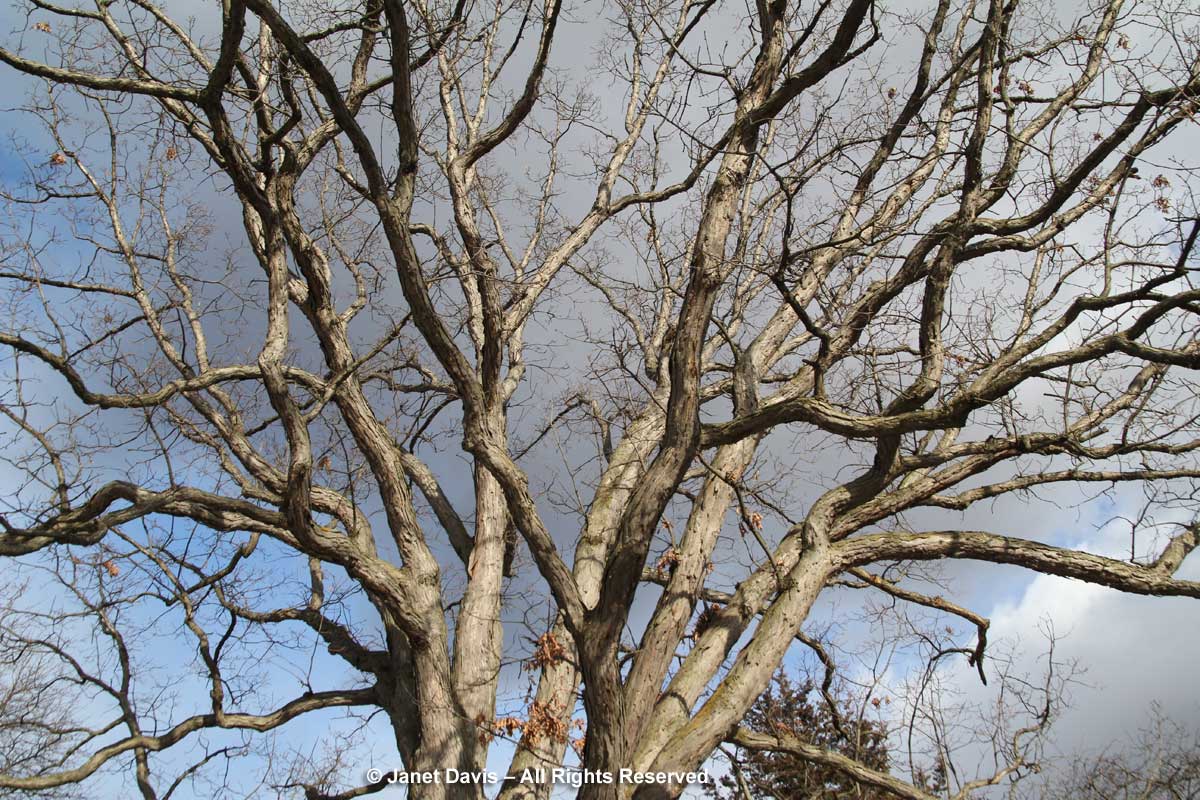

Quercus alba – Eastern white oak: At maturity, the white oak wears the word ‘majestic’ naturally. Maturing at 60-100 feet with a spread up to 50 feet (15 metres), its stocky trunk with scaly, grey bark often peeling in plates and patches, last year’s leaves hanging on in places to ……

…. its massive canopy and large limbs – all describe the tree many naturalists revere as the best in the forest. Listen to Donald Culross Peattie, from his wonderful A Natural History of Trees of Central and Eastern North America: “If Oak is the king of trees, as tradition has it, then the White Oak, throughout its range, is the king of kings…no other tree in our sylva has so great a spread. The mighty branches themselves, often fifty feet long or more, leave the trunk nearly at right angles and extend their arms benignantly above the generations of men who pass beneath them. Indeed, the fortunate possessor of an old White Oak, owns a sort of second home, an outdoor mansion of shade, and greenery, and leafy music.” Here is an autumn image of an “outdoor mansion” built of white oak.

Quercus macrocarpa – Bur oak: Not particularly well-known, even in southern Ontario where it is the most common native oak, this eastern North American tree defines “adaptable”. It likes cold winters and hot summers and tolerates a variety of soil types and moisture (though it is generally found on flood plains). Rugged and handsome with ridged, grey bark on a tree that reaches 50 to 100 feet (15-30 metres), depending on conditions, it is a pollution-tolerant choice for those who want a sturdy, wildlife-friendly native oak.

Quercus palustris – Pin oak: Native to the Carolinian zone near Lake Erie, pin oak prefers moist places (“palustris” means water-loving) but seems to survive in Toronto with normal garden irrigation. It tolerates clay but must have acidic soil; alkaline conditions will cause chlorosis and yellowing of the leaves. Its neat, pyramidal shape, reasonable height (60 feet – 18 metres) and beautiful fall color recommend it – provided soil pH is considered. This is the dense horizontal branching of a pin oak in winter. Note that the bark is changing its habit from grey-brown and fairly smooth to thinly-ridged and furrowed.

Here is the spectacular fall colour of pin oaks in Toronto. The orange leaf colour in the tree at left is almost certainly a result of chlorosis from localized alkaline soil.

Quercus rubra – Northern red oak: Perhaps because they grow all around us, along with white pines, on the granite bedrock of Lake Muskoka, I adore Northern red oaks. From their boughs, I hear the cheeky call of the blue jays, the chattering of chickadees, the peeeeep of the foraging downy woodpecker. Their abundant acorns feed squirrels and chipmunks. They turn glowing amber to deep red in autumn, long after the red and sugar maples have lost their leaves. Up there, the enemy is a dry summer and the odd infestation of army caterpillars. They tend not to grow as tall on granite as red oaks do here in the city, where they can reach 60 to 70 feet (18-21 metres) and a spread of 40 – 60 feet (12-18 metres), with greyish bark ridged with shallow furrows.

Quercus Crimson Spire™ – Hybrid Oak: There are several fastigiate oaks for use in smaller spaces, but this tightly columnar hybrid selection (Quercus ‘Crimschmidt’) of English oak (Q. robur) and white oak (Q. alba) is a stunning tree. It grows to 45 feet (14 metres) tall and 15 feet (4.5 metres) wide. As for the winter bark, there are so many marcescent leaves held on to Crimson Spire until spring, it is truthfully somewhat difficult to appreciate the bark without standing right beside the trunk.

Robinia pseudoacacia – Black locust: On a warm, late spring night, sometime around the first week of June in Toronto, an enchanting perfume wafts on the air – a scent that reminds some people of orange blossoms. If you chase it down, or rather “up”, you’ll find it’s coming from the abundant, white flower clusters of a tall tree with pea-like leaves. So sweet are the flowers of black locust that the volatile oil has been used as an absolute in the perfume industry, and the flowers produce a honey so clear, it’s said to look like the glass that holds it. Though indigenous to the central Appalachians, black locust has successfully made its way throughout North America and Europe – partly through commerce, and partly through its highly invasive self-seeding. There is no mistaking the bark of a black locust; it is thick and deeply grooved in a ropy pattern, on a trunk that’s often ramrod straight, as below. Though certain populations of very straight, high-branching black locusts were lent the name ‘shipmast locust’, the heavy, decay-resistant wood was evidently used for ship keels, not for masting, which requires lighter softwoods.

Salix × sepulcralis ‘Chrysocoma’ – Weeping willow: What can you say about a grand weeping willow? In late winter or early spring, when the long shoots brighten and the dainty catkins open, it’s as if the tree draped itself with dangling jewelry of the finest gold. Of course, you can also say the wood is brittle and prone to breaking, the fallen shoots make a terrible mess in small gardens, the tree wreaks havoc with underground plumbing and though it’s a rapid grower, it also declines quickly. Weeping willow bark is deeply grooved with patterned ridges.

Sorbus aucuparia ‘Rossica’ – Russian mountain ash: Another ultra-hardy pyramidal tree for the small garden, this selection of mountain ash bears clusters of white flowers in late spring and bird-friendly orange fruit in autumn as the compound leaves change colour to copper-orange. It grows around 30 feet (9 metres) tall with an 18 foot (5.5 metre) spread. On young trees, the bark is dark-brownish-grey and shiny with prominent lenticels; as the tree ages, the bark splits and develops cracks and scales. Mountain ash, or rowan as it’s called in Britain, rarely lives more than 80 years, and is susceptible to a number of diseases.

Stewartia pseudocamellia – Korean Stewartia: Though they are fine collector plants, there aren’t many stewartias in the Toronto region; they are not reliably hardy and need moist soil and protection from late day sun. I photographed my little winter specimen in a courtyard at the Toronto Botanical Garden, where it gets morning sun and is sheltered from cold wind. However, it’s tempting to seek out one of the few specialist nurseries that sell stewartia,for its luscious, camellia-like, white, June blossoms, its magnificent autumn leaf colour and this gorgeous mottled cream-and-brown bark. Korean stewartia grows to 40 feet (12 metres) with a 30 foot (9 metres) spread, beginning to branch outward very close to the ground.

Tilia cordata – Littleleaf linden: When the lindens – or, as the English call them, “limes” – flower in early summer, the air is sweet beneath their boughs. Bees, hover flies and butterflies buzz in the flowers, as befits a genus that produces a monofloral honey. In the United States, basswood (T. americana) and white basswood (T. heterophylla), aka “the bee tree” are the beekeeper’s friends, but in eastern Europe, many tilia species are used for honey production. (See my pollinator array photo below). Littleleaf linden has been a popular street tree and specimen tree in Toronto, but those who have tried to garden under it rue the gloomy shade from its broad crown. It is densely-branched and reaches 60 feet (18 metres) with a 40 foot (12 metres) spread. Linden bark is grey and shallowly fissured.

Pollinators forage on linden flowers, below. Clockwise from top left, metallic green bee, swallowtail butterfly and European honey bee on American basswood (T. americana) flowers; hoverfly on Caucasian lime (T. x euchlora) flowers. Large-scale bumble bee deaths of bees nectaring on Tilia species have been reported in the U.S. and Europe, but such toxicity is not well understood. (I have personally seen bumble bees lying in gardens under flowering lindens). It is now hypothesized that bumble bees will often expend all their energy foraging on lindens whose nectar is depleted, leading to collapse and death.

Ulmus americana – American elm: It is bittersweet looking up into the winter crown of a mature American elm, for this old tree is a survivor of a plague that decimated the landscape of its kin. When Dutch elm disease was first discovered near port cities in eastern North America in 1930, imported from Europe on elm logs to be milled for veneer, there were an estimated 77 million elms on the continent. Six decades later, that number had been reduced by 75%. Today’s surviving trees stand alone, like this one, its grey bark ridged and fissured, its arching limbs (those that have not fallen to ice storms) giving way to the elegant drooping branchlets that mark its profile as unique.

Ulmus pumila – Siberian elm – Here is the winter bark of a successful invader, a tree once used for hedging in my neck of the woods, as one might use beech or privet. But Ulmus pumila is no wimpy privet; it ‘hedges’ its bets by waiting until the gardener is not looking, then shoots for the moon. Paradoxically, its specific epithet means ‘dwarf’, but it is anything but small. This tree, for example, with its diamond-furrowed bark and adventitious shoots emerging from cankers on the trunk, is well over 60 feet (18 metres).

Zelkova serrata – Japanese zelkova: The stately zelkova is my final winter bark entry, and a worthy one at that. This elm relative has grey-brown, beech-like bark with raised lenticels, exfoliating as the tree ages. Pollution-tolerant, it is often planted as a fast-growing street tree, especially the cultivar ‘Green Vase’, which features ascending limbs, an upright shape and excellent fall colour. Zelkova reaches 70 feet (21 metres) at maturity with a 50-foot (15 metres) spread.