And now for something completely different….

What follows is an adaptation and extension of an essay I wrote for my old website in February 2008, when I learned about California singer-songwriter John Stewart’s death. You’ll find that below in Chapter 1. The essay launched a personal journey that saw me working with John’s music to create a narrative treatment that would potentially bring his music to the stage. In the course of that journey and by some measure of serendipity, I shared the project’s theatrical potential with an Australian stage producer who encouraged me in the project. Later, we both spent time in Marin County, California with John’s widow Buffy Ford Stewart. That part is in Chapter 2. It is my fervent wish that some day there will be a Chapter 3.

**********

Chapter 1 – JOHN STEWART: POET WITH A GUITAR (adapted from an essay published in February 2008)

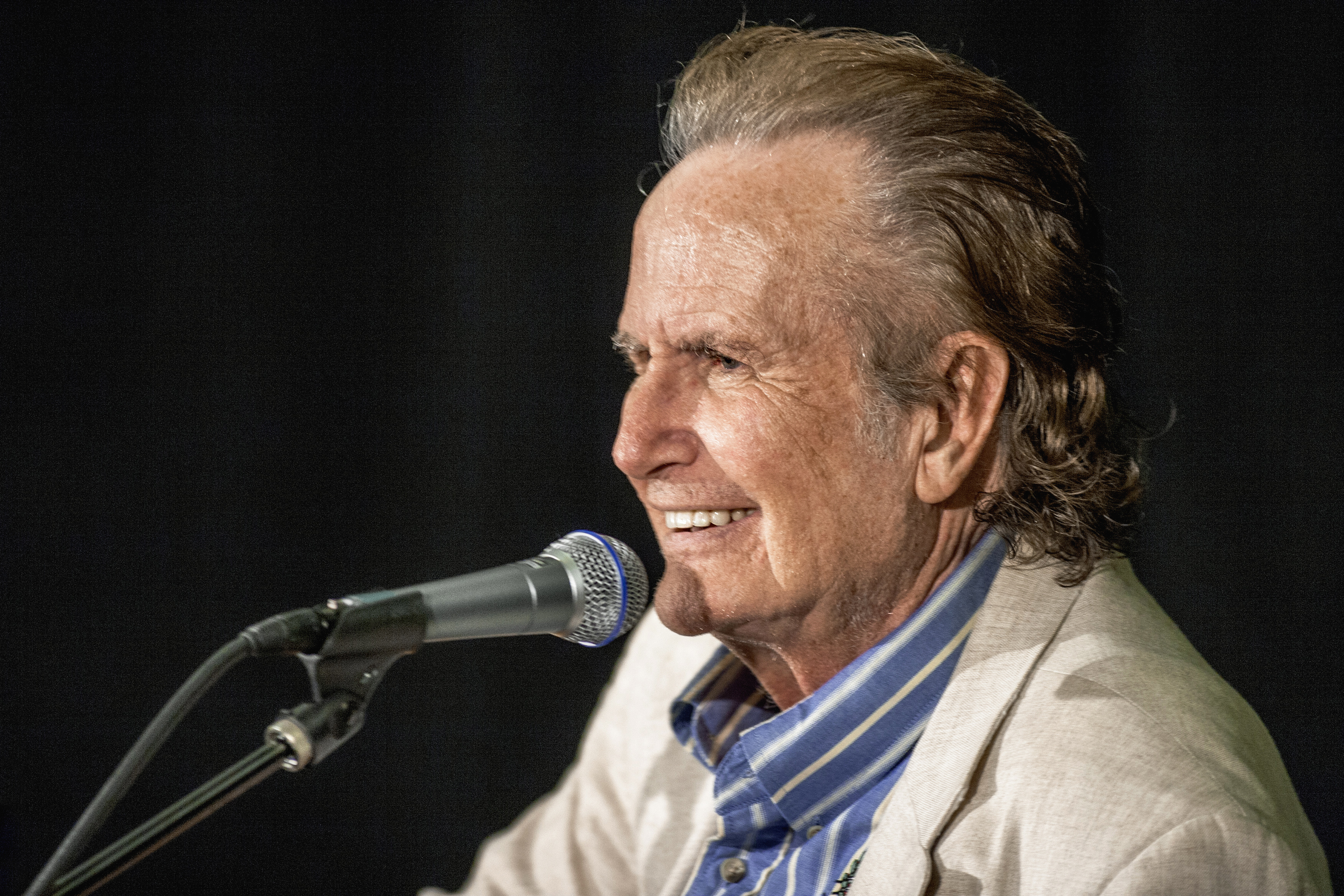

Singer-songwriter John Stewart died in San Diego on January 8, 2008 with his family at his side, by all accounts peacefully and without pain. He was 68 years old.

I like to think that if America’s poet laureate of the modern folk song had been given a chance to sum up his five-decade career, he might have struck a humble note, perhaps with the words from Mother Country, one of his best-loved songs:

“I was just another person, doing the best I could.”

Then I imagine him smiling and adding:

“But I did it pretty up and walking good!”

He called himself the “lonesome picker” and he was all of that: fiercely independent, solitary in his art and mildly disdainful of the corporate music machine. (He penned a song about Nashville titled Never Going Back – recorded in Nashville.) Working hard to pay the bills and keep his musicians around him, he toured small venues in the U.S. and Europe where an adoring cult of fans called the Bloodliners (who took their moniker from his stunning 1969 album California Bloodlines) would gather and cheer him on, then compare notes in chat rooms on the internet later. Those in the know shook their heads in wonderment that he wasn’t more famous, that he hadn’t really made it big after his early success. But in a way that solitary path was predestined, for he often seemed to embody the lyrics in his own songs, like ‘Ghost Inside of Me’, which Nanci Griffith covered on her album Clock Without Hands:

Every prayer I could be praying, every promise I’m betraying,

Every price that I am paying, is like a ghost inside of me.

Every road I could be taking, every dream I am forsaking,

Every heart that’s out there breaking, is like a ghost inside of me.

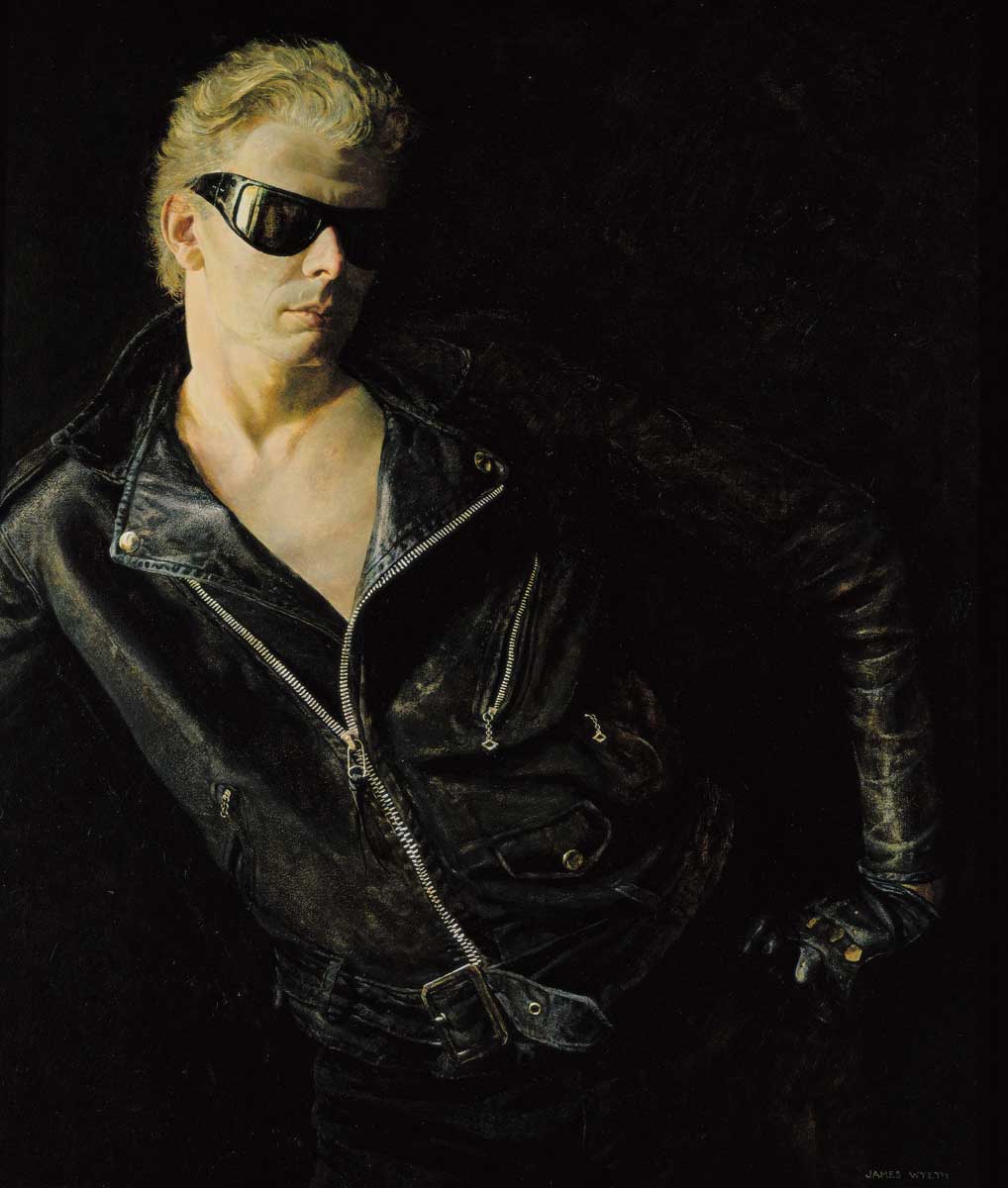

For those of us who love folk music, John Stewart was much more than a lonesome guitar picker; he was a highway troubadour, a poet-of-the-prairie, a rider-of-the-rails and a painter-in-song of the vast American landscape. Artist Jamie Wyeth once said: “John Stewart has achieved in song what I attempt in paint.” In fact, it was while sitting in his Mill Valley home studio for weeks in the mid-60s, reading John Updike and staring at paintings by Jamie and Andrew Wyeth – including Jamie’s iconic Draft Age with its leather-bound lad…..

….that John was inspired to pen the lyrics for one of the first LPs this music-lover ever owned, Signals Through the Glass. Here is my video adaptation of John’s song Draft Age.

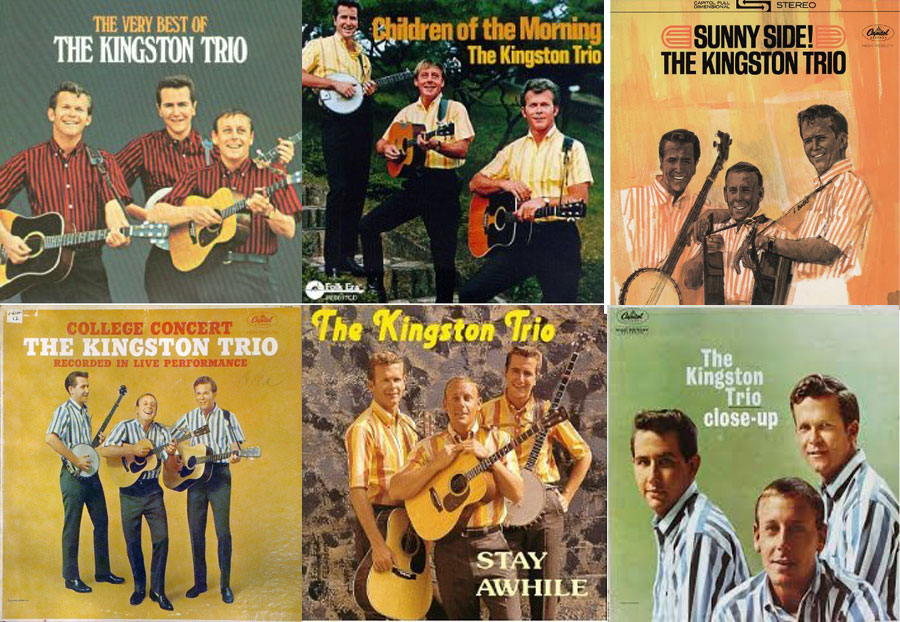

“They were song movies,” he said of his first album, noting that the title came from a sentence in a John Updike novel: “We are all so curiously alone, but it’s important to keep making signals through the glass.” Released in 1968, one year after ending a six-year stint with the famous Kingston Trio, who had hired John fresh out of school to replace Dave Guard, compose songs for the group and play bango and guitar,

……. and just after writing the hit Daydream Believer which became a defining moment for the pop band the Monkees, spending 4 weeks as the Billboard #1 hit in December 1967. Strangely, John had written it as part of a ‘suburban trilogy’, as he recalled in a 2006 video.

Signals Through the Glass featured John and his young singing partner, Buffy Ford, standing in a golden field behind the sun-refracting lens of John’s friend and musican, iconic rock photographer Henry Diltz. I was fascinated by a shot on the album of a smoldering, dark-haired Stewart standing behind Buffy with her long, thick bangs, straight blonde hair and kohl-lined eyes. They seemed the essence of the post-Seeger folk era, with some California hippie thrown in.

Rather than a simple acoustic treatment, John and Buffy’s debut folk album was lavishly orchestrated. “I was such an Aaron Copland fan,” said John on the liner notes, “that I wanted these songs to be set in a Copland-like symphony.” Listening to the album again today, I marvel at the lush, operatic force of the lyrics, as if all the folk songs he’d written for the Trio were just overtures for this symphonic celebration of Americana.

It was 1968, the year after the “summer of love”, the year before Woodstock and a tumultuous season of assassinations, of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy. The Vietnam war was raging and protestors were marching. I was living in Vancouver, just turned 21 and doing what young women did in 1968…. having fun, working at my first job, enjoying music (especially folk music) and celebrating flower power.

Signals Through the Glass became a favorite of mine, along with Phil Ochs’s Pleasures of the Harbor, Joni Mitchell’s Songs to a Seagull and James Taylor’s self-titled 1968 debut. I played the album over and over that year, lowering the needle repeatedly on my favourites: Santa Barbara, featuring Buffy’s bell-clear voice; Cody, the wild-haired “forgotten son of some old yesterday”; Holly on my Mind (“those lyrics just came from the sound of my 12-string guitar” said John); and July You’re a Woman, an anthem to youthful lust with a percussive, locomotive beat, a soaring trumpet in the background and John’s distinctive, vibrato-edged baritone:

I can’t hold it on the road

When you’re sitting right beside me

And I’m drunk out of my mind

Merely from the fact that you are here.

And I have not been known

As the Saint of San Joaquin

And I’d just as soon right now

Pull on over to the side of the road

And show you what I mean.

After that, I lost track of Buffy Ford and John Stewart for almost 40 years. It wasn’t until I heard on the news that day in January 2008 that he had died after an evening out with Kingston Trio member Nick Reynolds and their respective wives that I began my own archaeological dig through the buried history of one of the unsung geniuses of American music. In doing so, I discovered that I’d missed a lot.

********

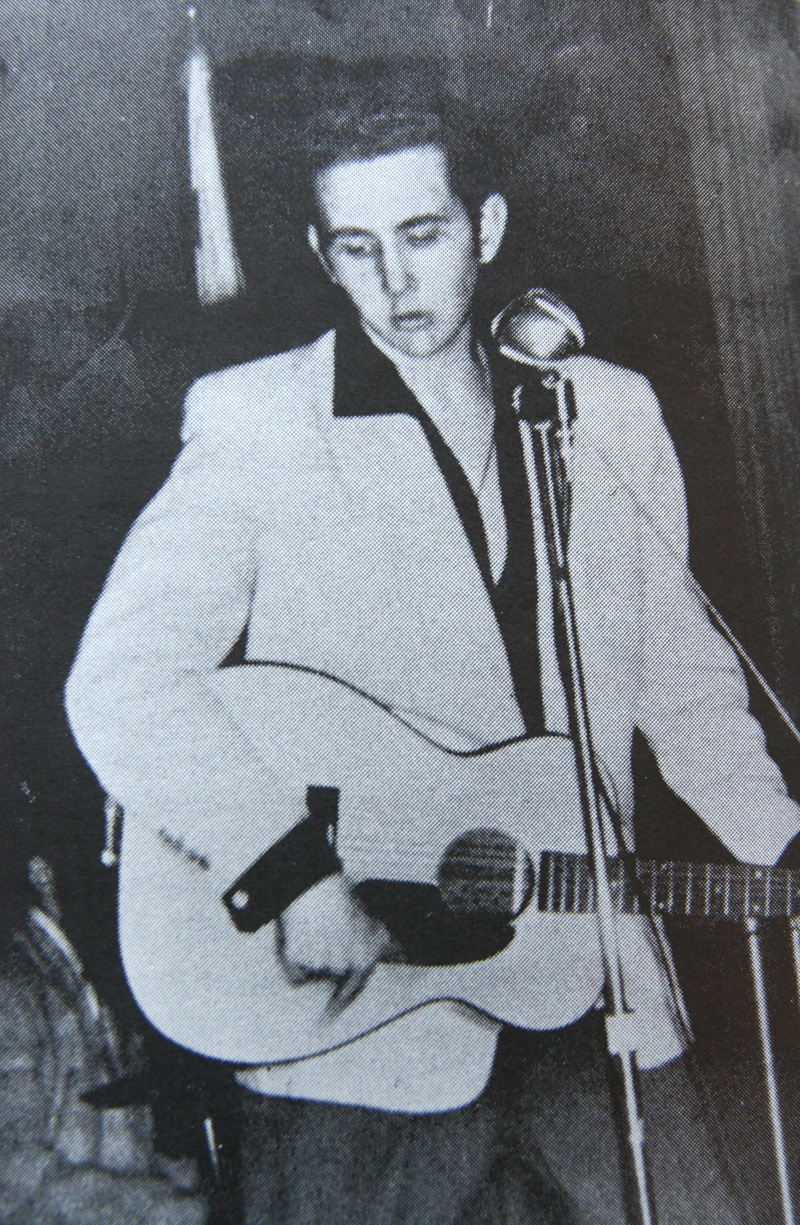

John Stewart was born in San Diego in 1939. His Kentucky-born father was a horse trainer and the family lived in racetrack towns like Pomona and Pasadena. Summers, he worked for his dad at the track, making a dollar an hour cleaning the tack and “walking the hots” (cooling down horses that have finished training). “That’s when I first started writing songs,” recalled John in an National Public Radio interview, “because there’s nothing more boring than walking the hots.” In a July 1979 interview with Rich Wiseman, he explained how the horse rhythm influenced his music.

“My father being a horse trainer, I grew up on the weekends and every summer on the racetrack, cleaning out horse stalls. As he’d work the horses, I’d go out to the infield and lie down with my ear on the ground next to the rail. I’d hear those horses coming around the clubhouse turn and then down the backstretch. The sound would get louder and louder. The rhythm was like this…(Stewart slaps his thighs to simulate beating of hooves).”

With Hank Williams and Tex Ritter playing on the tack room radio, it’s not surprising that horses became a major theme in John’s lyrics in songs like Mother Country with E.A. Stuart riding the old Campaigner, Sweetheart on Parade, stone-blind for the very last time. Listen to the horse trotting cadence of this 1969 song, which made a surprising and spectacular resurrection — literally, from a NASA vault of audio tape from the Apollo 11 moon mission — in 2019! (See my epilogue at the end).

Then there was Let the Big Horse Run from Phoenix Concerts, about Triple-Crown-winner Secretariat. And Back in Pomona from 1970’s Willard, in which John recalls the Blacksmith a-working in the blacksmith shop/And his anvil clanking and his coals were hot. All the Brave Horses and Wild Horse Road from Lonesome Picker Rides Again (1971) were elegies for John’s friend Robert F. Kennedy. But my favorite horse song is the rhythmic Golden Gate Fields from John’s 2006 album The Day the River Sang. In a voice as seasoned and craggy as well-aged scotch — reflecting his love of hanging out at the track photographing the horses — John sings about jockeys and junkies and two kinds of ‘horse’, each with the potential for grave danger:

And he’s looking for horse

To get through the day

That’s why he’s the shooter

And he’s willing to pay

The price of the monkey

Who takes him away

He’s a-betting on horses

That don’t ever pay

Although he began his song-writing career at the age of 10 with a song called Shrunken Head Boogie, it was while he was at Pomona Catholic High School that he formed a garage band called Johnny Stewart and the Furies, covering Elvis and Buddy Holly tunes.

At 19, encouraged by the manager of The Kingston Trio for whom he’d already written two songs, he formed a male folk-singing group called The Cumberland Three. In 1961, when Dave Guard decided to leave the Trio, John was hired as his replacement and spent 6 years with The Kingston Trio, writing many of their best known songs. Here they are on the Andy Williams Show in 1966.

After leaving the trio in 1967 to go out on his own, he began singing with Buffy Ford, who’d been part of the singing group The Young Americans and was being pursued by The Jefferson Airplane. Instead, she joined John, leaving the Airplane to sign Grace Slick. John and Buffy married in 1975 and had a son, Luke, a brother to John’s three children from his first marriage, Mikael, Amy and Jeremy.

So it’s not surprising that images of children skip through some of John’s lyrics. There’s little Ludi and her black widow spiders and woodpecker mama from Signals. Young Ernesto Juarez – “remember my name!” – pops up in the bouncing road song Omaha Rainbow from California Bloodlines. But the quintessential song about childhood – possibly the best song ever written about childhood – is Pirates of Stone County Road, also on Bloodlines and other albums. It’s about little Henry on “a summer afternoon somewhere in Kansas, or Illinois or Oklahoma” and a make-believe pirate ship cresting the rolling waves of John’s beautiful lyrics:

Where we’d stand on the bow of our own man-of-war,

No longer the back porch any more.

And we’d sail, pulling for China,

The pirates of Stone County Road,

All weathered and blown.

And we’d sail, ever in glory,

‘Till hungry and tired

The pirates of Stone County Road

Were turning for home

There are train tracks winding through his songs too, beginning with the almost operatic, history-infused Lincoln’s Train on Signals Through the Glass, about the train that carried Abraham Lincoln’s body from Washington D.C. to Springfield, Illinois. I created the video below to give the song a home.

On The Day the River Sang, there are two train tunes. Naked Angel on a Star-Crossed Train is about a songwriter’s inspiration while Midnight Train is a chugging locomotive of a song about trains carrying soldiers to and from battle, sometimes in coffins. In this one, John makes a pungent political statement: “El Presidente doesn’t care/Presidente has two daughters/You will never find them there.” Rosanne Cash, who considered John not just a close friend of twenty years but a wise mentor, had a hit with John’s Runaway Train.

Clack Clack from Willard (1970) tells of another funeral train, this time the slow-moving June 8, 1968 train carrying the body of assassinated presidential hopeful, Robert Kennedy, from New York to Washington D.C. As Robin Denselow wrote:

“John Stewart had first met Robert Kennedy in 1962 when he was Attorney General, while JFK was President. The Kingston Trio, then very major stars, were given a tour of the FBI Building in Washington, and were introduced to Kennedy at the end of it. Stewart and Kennedy got on remarkably well, the singer sent the politician a stack of albums, and the two began to see each other socially.”

“Stewart and Bobby Kennedy kept in touch, even after Stewart left the Trio in 1967 to concentrate on a solo career. He played and campaigned for Kennedy when he ran for the Senate, and then in 1968 the Senator rang with an even more serious request. He was running for the presidency, on an anti-war ticket, and he wanted Stewart to help, on what Stewart would later sing about as ‘The Last Campaign’.”

“When it came to actual campaigning, Kennedy’s main support came from John Stewart, aided by Buffy Ford. (See below). They travelled everywhere with him on the campaign plane, and acted as his opening act, singing, and keeping the attention of the crowd until they could break into the campaign song and get the maximum reaction for the television cameras as the candidate appeared.”

Later, John released an album called The Last Campaign (1985), a suite of songs about Bobby Kennedy, backed up by Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham of Fleetwood Mac. The songs in the video below were recorded in a live concert in Phoenix.

It was Bobby’s song

That I wrote without trying,

Every word, every word.

Now that Bobby’s gone,

This is my way of crying,

When I heard, when I heard…

Metaphoric rivers also run through John’s lyrics in songs like Mucky Truckee River from Signals and Sister Mercy and The Day the River Sang from that 2006 album. A moody river features in Strange Rivers from Punch the Big Guy (1987), covered by Joan Baez a few years later……

The wind gusts through his songs too. As John said to an interviewer who asked about his metaphorical use of the elements: “The wind calls the sailor, it waves the flag, it brings the dust, it clears the storms, it is the messenger of the universe. There are cosmic winds, the north winds, and monsoons and southern wind.” Chilly Winds was a song John co-wrote with John Phillips of the Mamas & Papas in a rowboat in Sausalito Bay while Scott McKenzie (“If You’re Going to San Francisco, Be Sure To Wear Some Flowers in Your Hair”) handled the oars. John eventually recorded it with the Kingston Trio and it forms the name of the website containing his musical lyrics. The 1977 album Fire in the Wind contained not just the wind-blown title track but Seven Times the Wind, On You Like the Wind, Promise the Wind and Fire in the Wind. The lovely song Wind on the River (with Phil Everly harmonizing) debuted on Dream Babies Go to Hollywood (1980).

Prairies and grasslands seemed to fascinate John as well, in songs like Hearts of the Highlands (from The Secret Tapes); Wheatfield Lady from The Complete Phoenix Concerts(1974); and Dark Prairie and Nebraska Widow from Signals Through the Glass. Then there wasYou Can’t Go Back to Kansas from The Last Campaign, performed below live at a 1981 Tommy Smothers-hosted Kingston Trio & Friends Reunion concert:

With more than 400 original songs and some 60 albums to his credit over four decades, many musicians worked with John before making it on their own. James Taylor played guitar and Carole King played piano and sang backup on John’s 1970 album Willard. That album’s title song features an interesting back story that came to light as I was doing research for this essay. It turns out that Willard was a real person, Willard Snowden, an alcoholic, African-American handyman from the Little Africa community in Chadds Ford, PA. He worked for painter Andrew Wyeth in the Brandywine Valley and posed for many of the artist’s most affecting portraits.

The Drifter, 1964 drybrush and watercolor on paper The Phyllis and Jamie Wyeth Collection © Andrew Wyeth/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

John came to know Willard when he and Buffy spent time with Jamie Wyeth in the late 1960s. For me, this song reveals not just John’s musical talent, but his great depth of compassion. The compilation below contains the song, with drummer Russ Kunkel playing his knees and Chris Darrow playing fiddle.

Other artists covering John’s songs include Pat Boone, Burton Cummings, Ronnie Hawkins, Frankie Laine, Anne Murray, Lobo, Lovin’ Spoonful, Barry McGuire, Kate Wolf and Glen Yarbrough, among many others. As a young woman, I saw Harry Belafonte do a lyrical take in concert on John’s Missouri Birds from California Bloodlines (1969).

One of John’s close friends and collaborators was Lindsey Buckingham of Fleetwood Mac, who wrote the song Johnny Stew for his pal after John lost his contract with RSO in 1980; John responded by penning Liddy Buck. Ironically, Gold the one song that actually went to Top-5 from John’s best-selling 1979 Bombs Away Dream Babies, on which Stevie Nicks sings backup, is my least favorite of all John’s outings, perhaps because the rock-and-roll style just doesn’t seem to suit the man I think of as a king of California folk. But it is the song many younger John Stewart fans know best.

For many weeks in the late winter and spring of 2008, John Stewart CDs dropped through my mail slot. However, I think one of the finest overall offerings is the last one, The Day the River Sang, recorded in 2006 when John was officially a senior citizen and, as I wrote above, exhibited a wonderfully rich old man’s voice. Appropriately, there’s an elegiac quality to many of the songs on this CD. New Orleans, co-written by Buffy, has wisps of Dixieland jazz and Delta blues backing bittersweet lyrics about not getting to see the Louisiana city before Katrina had levelled it. Broken Roses sees John riding “the tired road” of “weathered dreams” in a voice that brings to mind John’s friend Tom Waits. But perhaps because I spend my professional life in gardens and natural places, writing about them and photographing them, I have a special feeling towards the achingly beautiful Jasmine. You can almost smell the fragrance of the night-blooming jasmine and roses wafting through the lyrics, as John’s rugged voice takes him on a final walk through those California canyons. I chose that song as the soundtrack to a video homage of John’s musical career from 1960 to 2008.

In a reply to a fan on a Fleetwood Mac internet Q&A forum, John once said: “I tend to write about the same subjects, the resilience of the human spirit, the power of hope and the great American myths and realities.”

So thank you, John Stewart, Johnny Flamingo, old lonesome picker, for keeping tabs on the human spirit all these years, for infusing your songs with hope, and for immortalizing all those American myths and myth-makers, large and small, famous and humble. And I’m so happy that I became reacquainted with you and Buffy – your Angel Rain – once again.

************

Chapter 2 – DAYDREAM BELIEVER: THE JOHN STEWART SONGBOOK

So that was the first chapter. The second chapter actually began the year before my John Stewart essay, on a beautiful spring evening in New York City. It was May 30, 2007 and I was in the city to do some photography. At the end of one long day in the Bronx, I decided to relax with dinner at my midtown Manhattan hotel followed by a Broadway show. A few hours later, I was in my theatre seat reading the program for The Year of Magical Thinking, Vanessa Redgrave’s one-woman play based on Joan Didion’s devastating memoir about the death of her husband.

A gentleman sat down beside me. We read our programs in silence for a few minutes, then he asked where I was from. When I said “Toronto” he smiled and said he’d be in Toronto himself in just a few weeks presenting a show at our symphony hall. He, introduced himself: Andrew McKinnon, a theatre producer from Sydney, Australia and he was in New York having meetings and looking at theatres for his productions. After the show, we walked together for a few blocks towards our hotels. I gave him my card and told him to call in mid-June when he came to Toronto. He said he’d arrange to have complimentary tickets to the show and hoped we could join him. We said goodnight and went our separate ways. One week later, I received an email from Andrew arranging for the tickets for the June 16th performance. Because I was out of town, our son went in our place and enjoyed the show with Andrew, who introduced him to the cast and enjoyed a drink with him later. Andrew returned to Sydney and we kept in touch occasionally by email, comparing notes from time to time on plays seen and books read.

Fast forward eight months to February 2008. By then, I’d purchased more than three dozen Kingston Trio and John Stewart CDs, including some of the more obscure ones from John’s business manager Paul RyBolt.

I’d written my John Stewart tribute essay (Chapter One, above) and put it online to many favourable comments from his legion of fans. Stepping into this world was a departure from my day-to-day work, where I’d photographed and written about gardens and nature for two decades by then, with newspaper columns and a flourishing freelance career. But I was always a music-lover, and the 1960s folk era was my time. I was a theatre lover too, and as I listened over and over to the songs I’d acquired, I began to imagine what a superb theatrical experience John’s music would make.

There was so much history wrapped up in his life and work, beginning with the Kingston Trio days. John was intensely aware of the political battles for civil rights being fought in the U.S. but had limited success convincing his partners. As Robin Denselow wrote in his 1990 book, When the Music’s Over, The Story of Political Pop:

“The Trio started off the sixties folk boom, and then got left behind, largely because Nick Reynolds, Bob Shane and Dave Guard all saw themselves as entertainers who shouldn’t mix politics with music. John Stewart, who took over from Guard in 1961, felt differently, but knew he couldn’t change their attitudes ‘because the Trio trying to be political would have been ludicrous. It would have killed the group. Just like when Culture Club came out in America with that record ‘The War Song’, and it just killed them dead, because it didn’t fit.’”

But John did usher the Trio into more political territory with 1962’s New Frontier. The title was from John F. Kennedy’s 1960 acceptance speech to the Democratic National Convention; as a slogan, this “frontier of the 1960s” embodied his progressive aspirations for everything from social welfare to civil rights to space exploration. And he wrote what is arguably the most political song the Trio sang, Road to Freedom:

John’s own consciousness was awakened in March 1965, when he marched for three days behind Martin Luther King, Jr. in the Selma to Montgomery March, along with singer and civil rights activist Harry Belafonte and a large cast of singers, actors and entertainers. John told Robin Denselow, he joined…..

” ‘because if I was to have any credibility at all, I couldn’t just sit in Mill Valley, California, writing songs. You had to get into the fire, and I’m really glad I did, though it was very frightening. I stayed in this bombed-out church in Selma – the windows had been dynamited out, and we had to outrun the rednecks with baseball bats. It was like being in a war zone in your own country.’ “

At the conclusion of the march, as Denselow wrote, “Stewart left Montgomery lying on the floor of a car along with Yarrow and Belafonte, so they wouldn’t be seen by the Klansmen. They escaped unharmed, as did (Pete) Seeger, who had a nervous wait at Montgomery airport, where there was no police protection.”

Then there was his political campaign work with Bobby Kennedy; his long relationship with the NASA Mercury astronauts John Glenn and Scott Carpenter; his love for Buffy and their 40-year long duet together; his children; and most of all, his celebration of the great American dream, big and small, in hundreds of affecting songs.

I sent the link to my essay to Andrew McKinnon on March 4th. The next day, he responded. He said he remembered Daydream Believer and Armstrong from his youth, and he looked forward to hearing John’s songs, especially the ones about Bobby Kennedy. I wrote back, confessing my hidden agenda. “I’m mulling over whether it would be feasible to write some sort of adaptation of his songs for the stage.” I went on: “I know that there are precious few musicals that generate one or two hummable songs, never mind thirty. I can’t tell you how often I’ve walked out of a musical and wondered what happened to the good music. I think I could put together (easily) a list of his songs that would be dynamite stage material. The trick would be in linking them somehow and I’m working on various themes from his lyrics that would become character-like: war, love, landscape, children, rivers, etc. Call it a folk opera.”

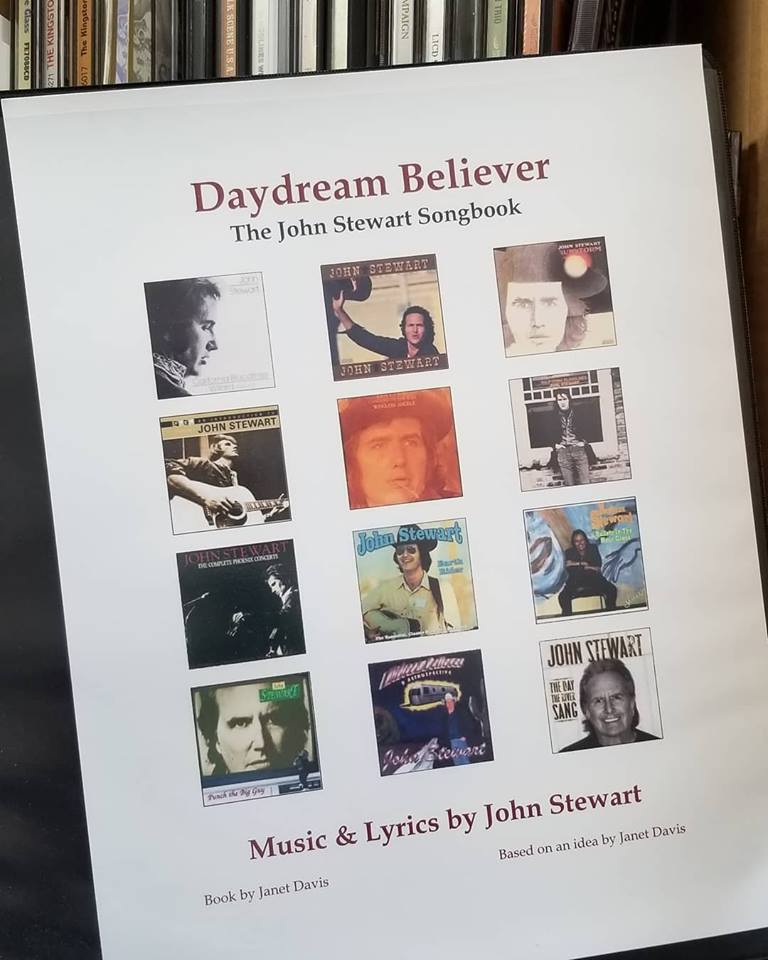

Then I started writing, working John’s songs into a loose theatrical framework that encompassed much of his 50-year career. I brought four of his characters to life and let them be the musicians who sang and strummed their way through his songbook. I introduced a muse and an angel (another of his songwriting themes) who related the history of the country to John’s songs. I called it Daydream Believer: The John Stewart Songbook, which had been his most famous and financially rewarding song. In 1967 just before the Kingston Trio disbanded, John wrote a trilogy of reflective songs about life in suburbia. When his friend and former Modern Folk Quartet member Chip Douglas came to John looking for fresh material for the pop singing group The Monkees, Jon chose one of those songs and it became a #1 hit for the group, staying on the charts for weeks. In the ensuing half-century, it’s also been recorded by Anne Murray, Pat Boone, the Four Tops, Shonen Knife and Susan Boyle. U2 has sung it on tour and it’s on every karaoke playlist. I put the script and two CDs in a binder and sent two copies to Australia. Then I left for Europe.

Six days later, as I was on holiday in Ireland, Andrew replied that he thought it had great potential, given the combination of John’s music and the historical events in which he took part. Then he said it was imperative that I contact Buffy, since her support for a musical would be critical. In May, I sent the script to California. Two days later, Buffy called me. A wave of relief washed over me as she said she had the script, but hadn’t read it yet. “I just wanted to hear your voice“. She was still in deep mourning, and promised to read it when she was ready.

Earlier that month, there had been a memorial for John at Pepperdine University in Malibu. Performers included John’s friends Timothy B. Schmit of The Eagles, Lindsey Buckingham of Fleetwood Mac, Davy Jones of The Monkees, the We Five and drummer Russ Kunkel. Rosanne Cash and the Mercury Astronauts John Glenn and Scott Carpenter spoke by video hookup. Trio member Nick Reynolds and Bobby Kennedy’s son Max spoke and there were performances by The We Five, Shana Morrison, Bill Mumy, Henry Diltz, Chip Douglas and John’s own band members, Dave Batti, Chuck , Dave Crossland, Bob Hawkins and John Hoke. And of course John’s family was there: Buffy, his children Jeremy, Amy, Mikael and Luke, and his grandchildren.

In July, I heard from Buffy. She had received a letter from Andrew McKinnon who was promoting the idea of a play, and was ready to read the script. She said, “The first time I called you I thought I was ready to read it and just wanted to hear the voice of the person who had written a musical on my husband in only six weeks when I could still not get out of my pajamas.” A few weeks later, she invited us to attend a tribute show to John to be held that autumn in Mill Valley, California, then spend a few days at her home going through the script. We both agreed.

So it was that I arrived in San Francisco to meet Andrew on November 4, 2008, that historic day when Barack Obama was elected president. The atmosphere in the city was electric, and I recall falling asleep in my hotel room to the sound of groups of young people walking on the sidewalk below chanting O-BA-MA, O-BA-MA! For the next few days Andrew saw to his own business and in between we discussed the project as we played tourist on the cable cars and Fisherman’s Wharf and Muir Woods.

Then it was time for the tribute concert at the Throckmorton Theatre in Mill Valley. It was a magical evening, a love-in for John. And the songs I’d listened to dozens and dozens of times as I worked them into the play came alive on the stage, through the music of Buffy, John’s band and his friends. Chuck McDermott had been at John’s side for more than 25 years; he and Buffy joined forces on Dreamers on the Rise.

“Once, we were dreamers on the rise,

We were the sun, where the sun never shines.

And we were gold, where the night bird never flies.

A long time ago we were dreamers on the rise.”

Dave Crossland and Buffy sang the stirring Cody, from Signals Through the Glass.

“Cody sang to me

A song about the great Montana sky

Cody sang to me

And I could see Montana in his eyes

And I could see Montana in his eyes.”

The John Stewart Band sang Never Going Back

“Every time I see that Greyhound bus go rolling down the line

Makes me wish I’d talked much more to you when we had all that time

Still, it’s only wishing and I know it’s nothing more

So I’m never going back, never going back

Never going back to Nashville anymore.”

Shana Morrison did a beautiful rendition of Runaway Train.

“I’m worried about you, and I’m worried about me

The curves around midnight aren’t easy to see

The flashing red warning, unseen in the rain

This thing has turned into a runaway train.”

Buffy picked up her banjo and sang her own version of California Bloodlines

“Oh, there’s California Bloodlines in my heart

And a California cowboy in my song

Oh, there’s California Bloodlines in my heart

And a California heartbeat in my soul.”

John’s friends rock photographer Henry Diltz, actor Bill Mumy (Lost in Space) and musician/producer Chip Douglas reached back to the early Kingston Trio days for a rollicking ‘Molly Dee’. (Henry and Chip had been half of The Modern Folk Quartet from 1962-66.)

“Here we go round again

Singin’ a song about Molly Dee

Far away I know not where

She’s the girl who waits for me”

Among the many other songs performed that night, there ws a tribute to Kingston Trio member and John’s dear friend Nick Reynolds, who had passed away a month earlier. The ensemble sang his favourite Trio song, Pete Seeger’s Hobo’s Lullabye.

“Go to sleep you weary hobo

Let the towns drift slowly by

Can’t you hear the steel rail humming

That’s a hobo’s lullaby.”

For the finale, the theatre rocked with John’s Gold.

“When the lights go down in the California town

People are in for the evening

I jump into my car and I throw in my guitar

My heart’s beating time with my breathing

Driving over Kanan, singing to my soul

There’s people out there turning music into gold”

The evening ended with a hotel room singalong, as John’s band members and friends strummed their guitars and sang their own John Stewart favourites and Shana Morrison gave us acappella versions of two of her father’s songs.

Two days later, Andrew and I were with Buffy reading through the script, listening to the music, making notes, pencilling in changes, watched over by one of John’s many paintings. Though Andrew came to feel his production talents were best suited for a different genre, he was so helpful in this process and continues to encourage the project.

The next afternoon, Buffy drove us to Bolinas on the coast. Though I didn’t include it in the play, Bolinas (1971) is favourite song for me, with beautiful harmonies and lyrics of California and those train tracks again.

Having listened to the song so many times in my office at home, it was lovely to be there walking at the ocean’s edge. Buffy and I shared a little moment of grace, knowing that it was John’s music that had brought us together.

Andrew flew back to Sydney and I returned to Toronto and started the hard work of marketing the play; sending the script and music to producers, often introducing John to them for the first time. It remains an ongoing project and a true labour of love. More than anything, it has been a privilege to spend these years immersed in John Stewart’s words and music.

Epilogue:

If you’ve seen the stunning 2019 documentary Apollo 11, you will have had the pleasure of listening to John’s 1969 song Mother Country as the astronauts in the command module return to earth. How did it happen?

There is a fascinating story behind its inclusion in the film, which was related by author David Kamp in the December 2018 issue of Vanity Fair.

“(Producer Thomas) Petersen was listening to this on-board audio when something caught his attention: while the three men were inspecting the condition of the lunar module, which Armstrong and Aldrin would be flying the next day, Aldrin casually said, “Let’s get some music.” And then Petersen picked up some faint baritone singing in the background. He initially took this to be a Johnny Cash song, but, after listening for more clues, he determined that what he was hearing was “Mother Country,” by the singer-songwriter John Stewart, off of Stewart’s then-latest album, California Bloodlines…..

“…..“Mother Country,” a bittersweet, not un-Cash-esque ballad about American heroism and the elastic meaning of the phrase “the good old days,” proved a perfect allegorical fit for the film. Miller and Petersen sought permission from Stewart’s widow, Buffy Ford Stewart, to use the song in Apollo 11, and she was happy to oblige; she and her late husband, it transpired, had been good friends in the 60s with some of the Mercury astronauts.”

For the young Kingston Trio member (John is second from right) who wrote These Seven, about the Mercury astronauts way back in 1962……

…… and for the 29-year old John Stewart who made sure Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin was taking his latest album California Bloodlines to the moon, it is a wonderful and appropriate achievement. If you have the chance, be sure to see the documentary. And on July 20, 2019, of c d, when we “saw a man named Armstrong walk upon the moon“. I’ll give John Stewart the last word.