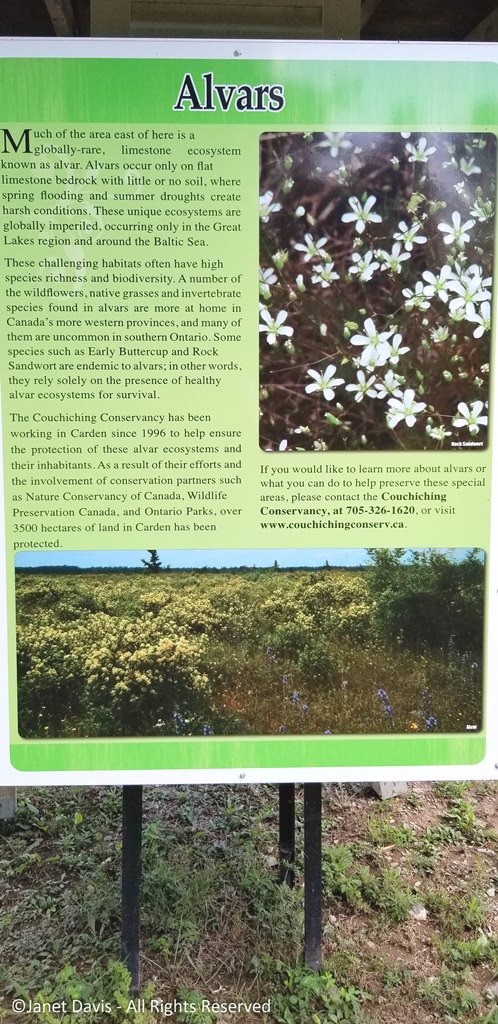

It’s a free day at the cottage and I pack a lunch and my cameras and head out on the highway to visit one of Ontario’s newest parks, the 1917-hectare (4,737 acre) Carden Alvar Provincial Park. I am an armchair geologist… well, in my own mind, where it’s possible to be anything I want to be. But having spent a few months reading John McPhee’s fabulous, Pulitzer-Prize-winning, 660-page anthology Annals of the Former World (1998) followed by geologist Nick Eyles’ engrossing Road Rocks Ontario (2013), I have decided to explore one of Central Ontario’s rare protected alvar habitats. I want to see for myself what Eyles describes as “these windswept grasslands that are now Ontario’s prairies.” Alvar is a Swedish word, first coined to describe limestone plains with little or no soil, exemplified by the biggest alvar in Europe, Stora Alvaret off the Swedish island of Öland. The Burren in County Clare, Ireland, is a large alvar. But in North America, the alvars are found near the Great Lakes, including Manitoulin Island and the Bruce Peninsula on Lake Huron, and Pelee Island in Lake Erie.

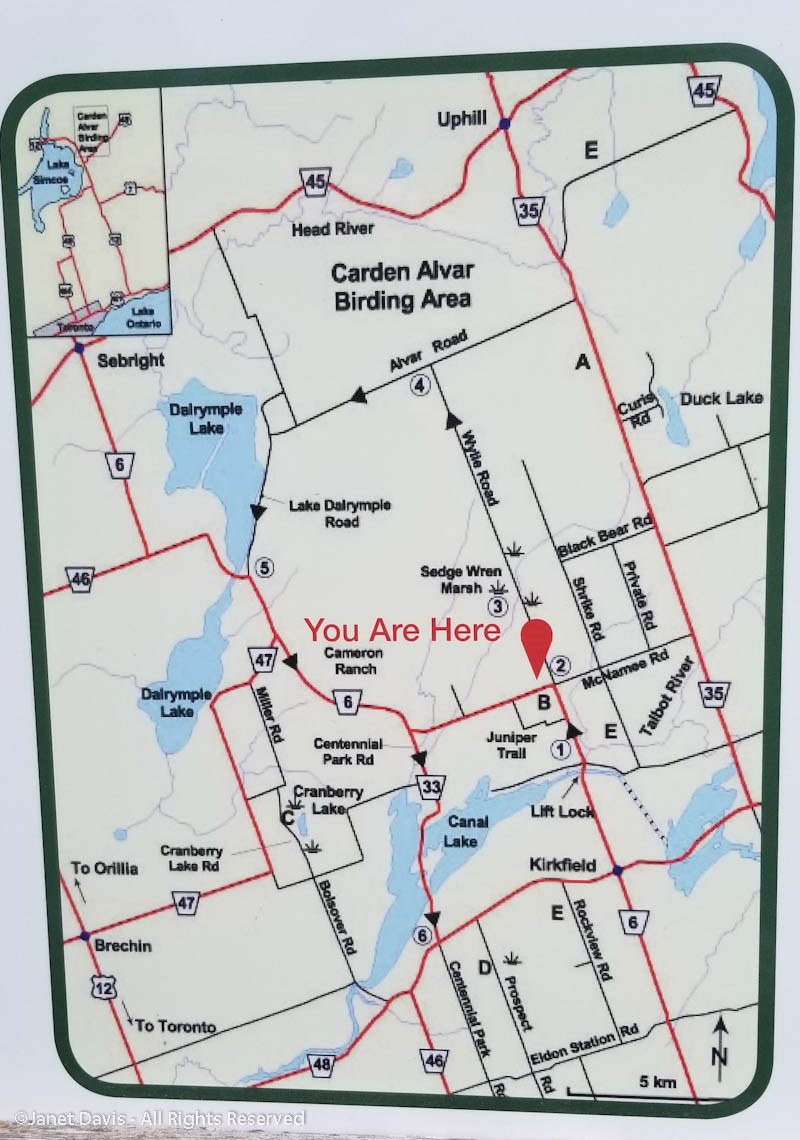

Located northeast of Lake Simcoe and east of Orillia at the western edge of Kawartha District (its map address is City of Kawartha Lakes), Carden Alvar is less than an hour from my cottage on Lake Muskoka. But as with any exploration of new areas, it’s a good idea to research thoroughly beforehand. This becomes clear as I drive blithely south along Highway 169, past Highways 46 and 47 where I should make my turn, while listening to the dulcet voice of Google maps telling me ‘Signal is unavailable’. In time I pull over and consult a map, turn around and retrace my route, and eventually come to the corner of McNamee & Wylie Roads…..

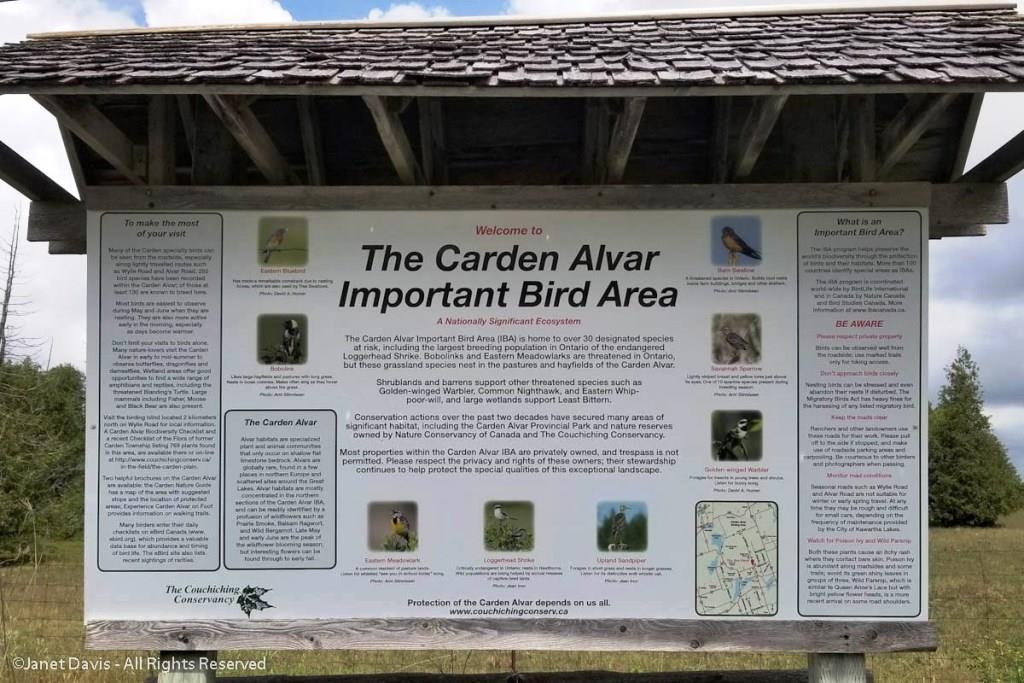

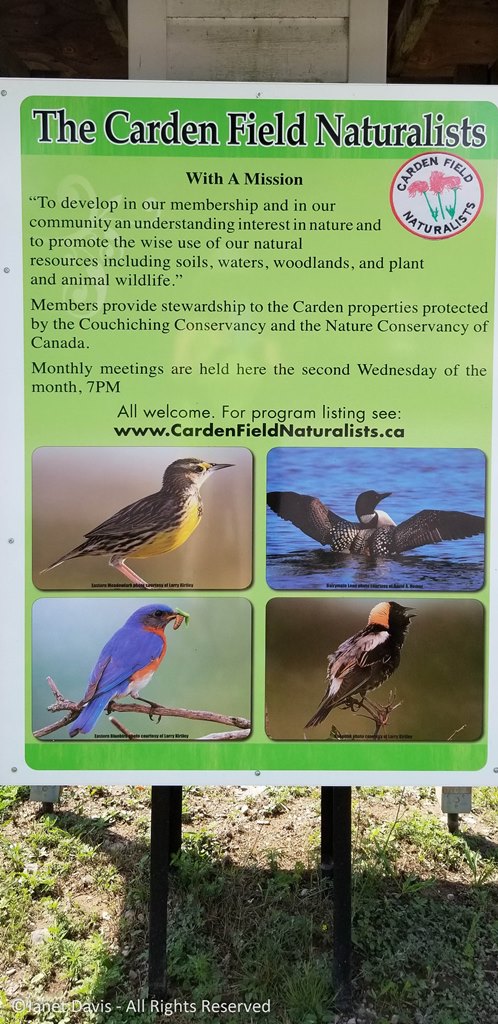

…. which, like much of the Carden Alvar, is considered an IBA – Important Bird Area. Eastern bluebird, bobolink, eastern meadowlark, savannah sparrow and the critically endangered loggerhead shrike are among many denizens of the grasslands, marshes and forest here.

It will be some time before I realize that I am not going to find a traditional ‘park’ with a visitor centre or the kind of facilities we associate with that term. Instead, I find a series of neighbouring farms with roadside signs describing their relationship variously to the Couchiching Conservancy, Nature Conservancy, Carden Field Naturalists and/or the Carden Alvar. I get out of my car at the sign for the Bluebird Ranch – clearly a clue for the bird that would be seen here in season.

I don’t see an alvar, but a wet path leads through a small meadow riddled with poison ivy.

I’m glad I changed from my flip-flops to running shoes, as there are warnings posted on all the conservancy signs. (Note to self: check to see if poison ivy prefers alkaline soil. We rarely see it on the granitic Shield in Muskoka.)

I walk back through the small pull-off parking space and kick at a plastic vodka bottle lying in the gravel. Clearly local folks come to Carden Alvar to party. But the gravel reminds me that the very fact that so many roads and building projects use crushed limestone is the reason that so much rural Ontario property is sold to quarrying companies. There is a real need to conserve alvar habitats, especially those that time and circumstance have kept fairly pristine.

Wylie Road is lined with numbered eastern bluebird nesting boxes. (Another note to self: Return in spring when the bluebirds are nesting!) As this blog on the Couchiching Conservancy says, “The bluebird is doing well in Carden, thanks to two things: first, a local man named Herb Furniss has spent the last few decades building and distributing white bluebird boxes throughout the region, quietly making a huge difference for these little birds; second, Wylie Road rolls through an area where more than 6,000 acres of grassland, forest and wetland has been conserved as natural habitat.”

I get back in my car and begin driving north on Wylie. Somewhere I saw that this is a 9-kilometre road, but that won’t be significant for a few hours. Minutes later, I see the sign announcing the conservation of the next property, Windmill Ranch. It thrills me that so many landowners forego profit for philanthropy, and so many ecological institutions devote themselves to saving properties like these from development.

I’m excited to spot a little outcrop of limestone in the farm field – i.e. the limestone ‘pavement’ or epikarst. It reminds me that much of the limestone here is under the soil, but where it peeks out or hasn’t been eroded to soil and planted to crops, the plant species it supports are unique, often rare and typically found on prairies.

Windmill ranch occupies 4 kilometres along Wylie. At 647 hectares (1600 acres), it was farmed for cattle by the late Art Hawtin – first with his dad in his 20s and 30s, then with his wife Noreen into his 80s. In 2006, the ranch was acquired by the Nature Conservancy of Canada in an arrangement with the Couchiching Conservancy; in 2014, it became part of the Carden Alvar Park. In writing this blog, I discovered that Art Hawtin was not just a favourite math teacher for 17 years, but was a POW held by the Germans in the same prison in Poland, Stalag Luft III, as the Allied fliers who escaped in 1943 in the breakout that would be celebrated in a book and the Steve McQueen film, The Great Escape.

As I drive along the road, grazing cattle move towards the fence and my car. I presume they’re used to being tended to here by ranch employees — the only people who likely use the road, along with bird-watchers. Parts of the properties under protection continue to be grazed or farmed for hay.

Before long, I come upon a small pull-off where I park. Just beyond is a little ochre-yellow bird blind.

I undo the latch and enter, gazing through one window…….

…… then the other. What lovely framed views.

I wish I was the kind of person who wakes up early and goes out with binoculars to check off avian species on a life list. But I’m not. I notice the species list (a little damp from rain) published by Bob Bowles of Orillia.

(An aside: I have fond memories of Bob, in the navy ball cap, coming to my own cottage in Muskoka one autumn to help my hiking pals and me identify mushroom species on our peninsula.)

When I go back out to get in my car, I’m rewarded with the sight of barn swallows diving across the road and returning to sit on the wire fence. Evidently, they are increasingly threatened by loss of habitat.

Here I see adults….

….. and sweet little chicks.

There seems to be a great abundance of wild fruit along the road: lots of staghorn sumac as well as non-native honeysuckle.

All around is the buzz of bees visiting the blue flowers of viper’s bugloss (Echium vulgare) and white sweetclover (Melilotus albus). Though they’re not native, they’re feeding every manner of bumble bee and solitary bee.

I stand for a while and listen to the meadow and the wind in the grasses.

The day before saw a deluge of rain in central Ontario, and the fields in lower sections are partially flooded. One of the characteristics of alvars is shallow soil and frequent flooding.

Wylie Road ahead of me is a series of giant, deep puddles stretching from one side of the limestone gravel surface to the other.

I stop at an interpretive sign for the Sedge Wren Marsh Walking Trail and get out of my car and begin walking in …..

….. but decide that the puddles on the path might be too much for my footwear.

Coming out I make my first sighting ever of wild fragrant sumac (Rhus aromatica).

Back in the car, I come to lovely wetland and open my car window to gaze at spotted Joe Pye weed (Eutrochium maculatum) and cattails (Typha latifolia) right beside me.

As I cross a rusty bridge, I gaze out across a fen with floating sedge mats and a forest of white spruce in the distance.

I adore central Ontario’s wetland plants, including the fluffy, white tall meadowrue (Thalictrum pubescens) here.

And then, of course, there are the usual alien suspects: bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare) and Queen Anne’s lace (Daucus carota).

From time to time, farm fields give way to fragments of woodland, like these lovely aspens. That ‘edge’ habitat bordering on open fields is excellent for attracting birds of all kinds.

A sign advises visitors not to block traffic on the road. I smile a little, since the only car I’ve seen in my two hours of dawdling along Wylie Road is mine! But it’s popular with birdwatchers, especially in spring. Have a look at this blog for some fabulous bird photos made in late May, when pink-flowered prairie smoke (Geum triflorum) appears to fill the fields.

Now I come to Art’s Ranch.

Staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina) is one of the most abundant native shrubs in Ontario, growing on both the northern Shield and the central limestone belt. Its fruits feed myriad birds and mammals.

Roads made of limestone tend to erode easily because limestone carbonates break down in water of any kind, and even more quickly in acid rain. I cross my fingers that my car is up to the rough conditions (I’ve never had a flat tire)…..

…. and begin to drive north, splashing deep every few minutes.

Finally, as I begin to think I’ll never reach the end of Wylie Road, I do. And here is the North Bear Alvar, a 325-hectare (800-acre) parcel of the Carden Alvar that was conserved in 2011. According to the Nature Conservancy of Canada, there’s a 4.5 kilometre ( mile) wilderness loop trail here “that leads you through a lush wetland where blueflag iris and swamp milkweed grow. Keep an eye out for turtles basking on logs or rocks…. Continue through a meadow of wildflowers, listen for the music of grassland birds, such as upland sandpiper, and watch for the flash of the brightly coloured golden-winged warbler.”

I drive west on this road and come to the definitive clue that I’ve been in the right place for the past 2-1/2 hours, a signpost for Alvar Road.

At the west end of Alvar Road, it intersects with Lake Dalrymple Road. I drive south along the lake and here I have my most thrilling avian moment – if not exaclty a notch on an alvar species list. High up on a power pole is a massive nest…..

…. in which two juvenile osprey are chirping their hearts out, waiting for their parents to return with fish.

Have a listen to their plaintive cries. (I have no tripod, so the extreme zoom on my little Canon SX50HS camera is put to the test.)

Back in the car, I continue driving south along the lake and come to the Carden Township Recreation Centre. The door is locked and the place is empty…..

…. but there are interpretive signs nearby promising wonderful flora on the alvar…..

….. and rare bird sightings.

I walk out on a path and see the same abundant milkweed meadows I might find near my cottage. Clearly, I am late for the alvar floral display, which seems to have peaked in late May and early June, but I see a lone monarch butterfly circling..

Back in the car, I drive a short distance south and come to the Lake Dalrymple Resort. I pull in.

When I ask the proprietor about the alvar flora, he looks puzzled. “There’s a sign back at the Recreation Centre”, he offers, as he scoops me an ice cream cone, I tell him there was no one at the rec centre. “Maybe another sign down the road,” he says, pointing south. (The flavour is Muskoka mocha, and highly recommended.)

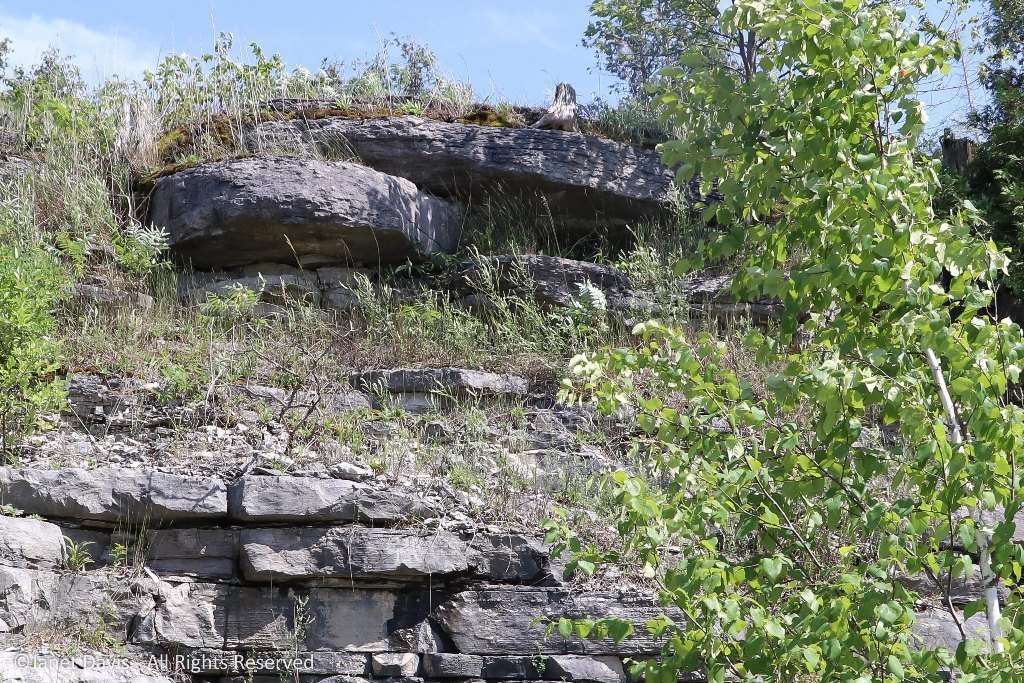

A short drive down Lake Dalrymple Road and I slam on the brakes. Looking east and up a rise through trembling aspens, I see the characteristic layers of a limestone shelf. When I set out in my boat on Lake Muskoka this morning, I left a shore of Precambrian gneiss that is somewhere between 1 and 1.4 billion years old.

Here, on the other hand, these exposed layers of fossil-rich limestone in the Bobcaygeon Formation were laid down in the Iapetus Ocean in the Ordovician era, roughly 500 million years ago. While sediment deposited when the glaciers retreated 10-12,000 years ago covers much of Ontario’s limestone, here in much of Carden Alvar, it forms the pavement (epikarst).

Finally, having driven counter-clockwise around much of the alvar, I come to the place that holds such appeal for me. It’s the Prairie Smoke Alvar, a 2006 donation by artist Karen Popp to the Nature Conservancy of Canada, and now managed with two other conservation bodies.

But I am a little puzzled, because from here, it just looks like a hayfield. Indeed, hay-baling is happening at this very moment. It will be days before I understand the relationship between the farms and the conservancies that manage them. Indeed there is a mandate for this hayfield: “Hay fields near the entrance of the property are being managed to support grassland breeding birds such as Bobolinks and Eastern Meadowlarks, and also provide grazing for several dozen White-tailed Deer in early spring.”

Understanding these relationships and the late May flowering on limestone pavement of many of the rare alvar species, including prairie smoke and Indian paintbrush will dictate a return trip next spring and a walk down this well-worn track to find them.

I finish my search for Carden Alvar in the small parking lot of the 1,214-hectare (3,000 acre) Cameron Ranch…..

…… and leap-frog rain puddles to stroll the boardwalk. Here, according to the Couchiching Conservancy, are “northern dropseed, tufted hairgrass, early buttercup, alse pennyroyal and prairie smoke.”

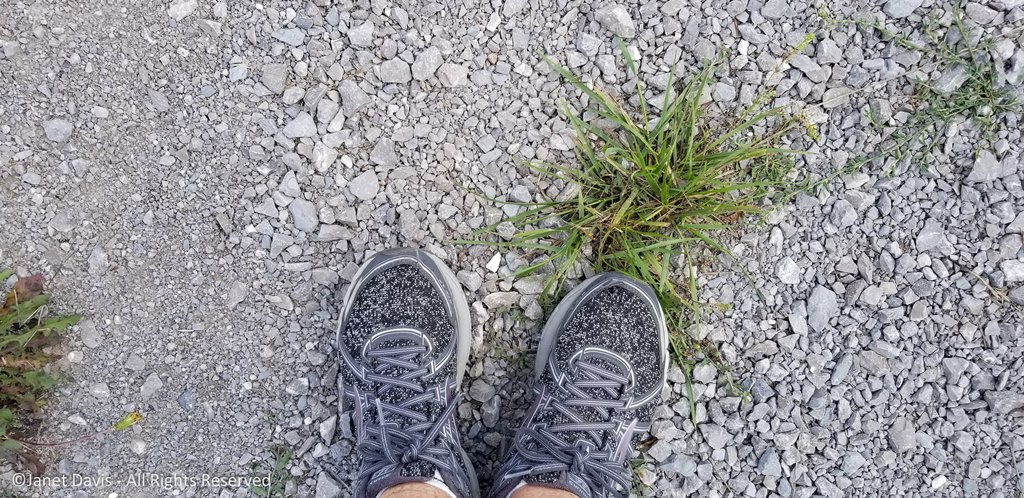

I’ve been exploring the alvar for 4-1/2 hours and it’s time to drive back to Muskoka. As I head back to my car, I gaze down at my feet standing atop limestone gravel. For decades, the only use that people made of central Ontario’s Ordovician limestone and dolomite was aggregate for roads and buildings or flagstone pavers for landscaping.. Today, intelligent, ecologically-attuned people understand that digging out more and more limestone quarries for human use eradicates vital habitat for many species that depend on these ecosystems. As I kick the 500-million year old gravel beneath my shoes, I give thanks for the efforts of the many conservancies that have secured vital protection for Carden Alvar.

And, of course, I promise myself a return trip next spring to see the prairie smoke in bloom.