It was a bittersweet summer in the milkweed patch in my cottage meadow on Lake Muskoka. There were monarch butterflies and hungry caterpillars. There were two chrysalis vigils. There was joy and sadness, and I learned a lot about this extraordinary and complex biological process called metamorphosis. This is my summer journal.

July 19 – I notice my first tiny monarch caterpillar on butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa) leaves in my dusty rock garden behind the cottage. I recalled a monarch flitting about purposefully about three weeks before, on Canada Day weekend.

Another is munching on the flower buds of a different plant of the same species.

The buds of this type of milkweed do seem to be a popular place for monarchs to “oviposit”, or lay eggs (with their ovipositor). The photo below is from 2012. A typical monarch will lay 200- 400 eggs in her laying period, which lasts between three to five weeks. And it’s estimated that 99% of those will not survive to maturity.

The upper leaves are also used, which makes sense since they’re tender and likely not as concentrated in latex, the plant’s defence mechanism, which can be toxic to caterpillars in strong enough concentrations (and also toxic to birds that try to eat the caterpillars or the butterflies). But just as milkweed plants have evolved to resist predation, monarch caterpillars have evolved to outwit the plants, by chewing carefully on parts of the leaf’s vascular system to keep the latex from flowing. Some milkweeds, like butterfly milkweed here, are also hairy and young caterpillars often “shave” the leaves for a long time before eating them. Check out this interesting video by a Cornell ecologist who has specialized in milkweed-monarch co-evolution.

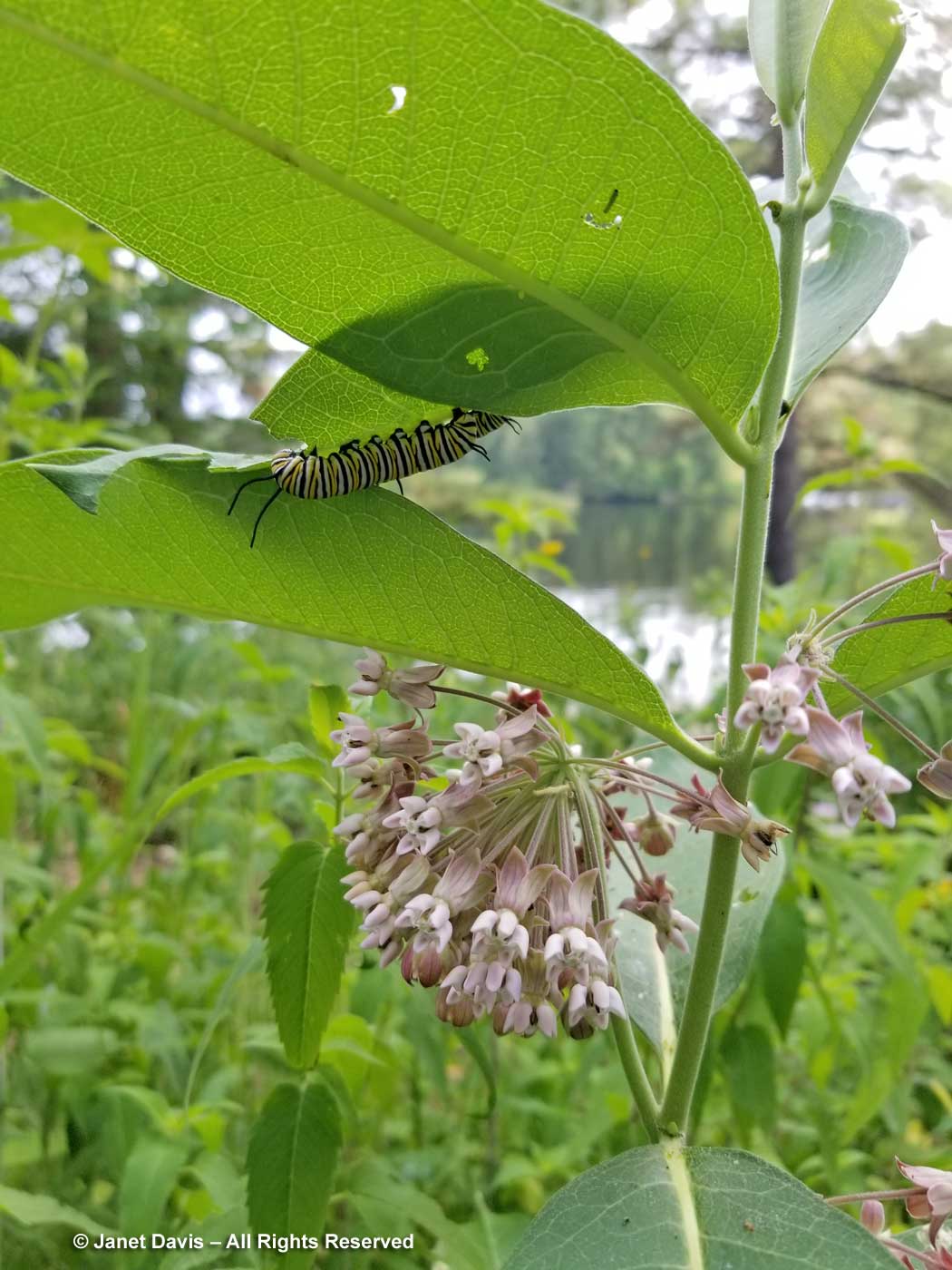

JULY 21 – Common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) showed up by itself in my meadows a few years ago. I love the fragrance and it’s a good nectar plant for many bees and butterflies, as well as food for monarchs. But I only have two plants and one is filled with caterpillars, while the other is empty.

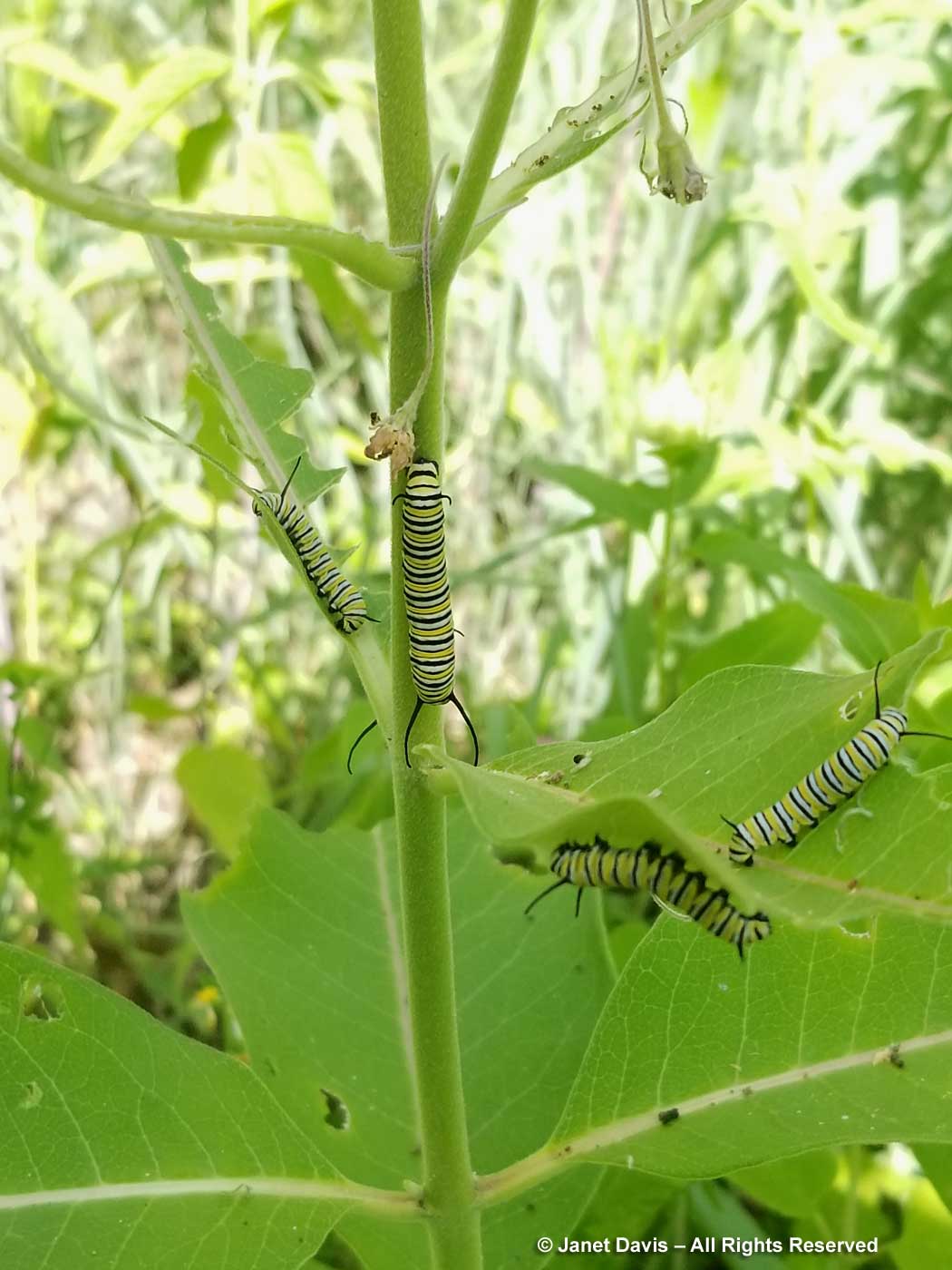

JULY 22 – Monarch caterpillars are eating and excreting machines. After the egg develops into the first tiny larva, i.e. caterpillar – called the first instar – approximately 3-5 days later, there are four subsequent developments that span roughly 9-14 days, depending on climate. Each time, the caterpillar molts or sheds its skin. In the photo below, you can see the top caterpillar in the act of excreting its waste, called frass. Its head faces the stem, and the antennae-like organs are called the front filaments or tentacles. There are 3 pairs of jointed true legs near the front; the knobby things behind are prolegs and there are 5 pairs of them fitted with hooks to hang onto leaves. Behind its head, the caterpillar has segments divided into thoracic and abdominal segments. The 8 abdominal segments feature tiny breathing holes called spiracles.

A milkweed plant is a messy place with this many caterpillars feeding.

Because my other common milkweed has no larvae, after checking online I decide to very gently relocate some of them from the rapidly diminishing plant nearby. At first they curl up in a defensive position.

But gradually they uncurl….

…. and soon they are climbing up the stem past the perfumed blossoms towards the tender leaves at the top.

JULY 23 – It is astonishing to see the efficiency of this munching army…..

…… as they strip the foliage and flowers from the new plant, too.

I make a little video of the caterpillars eating from the two species of milkweed.

I spot a tiny caterpillar and decide to try it on a plant of butterfly milkweed. It’s only later, after I watch it reject the other species, that I learn that while it’s fine to move caterpillars from one plant to another, they should be the same Asclepias species. It inspires me to create a whimsical little video for my Facebook page about this time in July to illustrate the quandary of “too many caterpillars, not enough milkweed”.

JULY 25 – On the dusty hillside behind my cottage, monarchs are on almost every butterfly milkweed plant. July has been so dry, I feel compelled to water these forgotten plants so they provide nourishment for the caterpillars. It’s only now as I’m writing this blog that I note the bent stem and realize that this caterpillar may well have chewed it carefully until it almost breaks, thus preventing the toxic latex from reaching the top leaves.

In the monarda meadow near the cottage where the common milkweed grows, the caterpillars are now on the move, looking for a place to make their chrysalis. I spot one climbing along a blade of grass..

JULY 26 – I spy another on a fleabane stem, below. Note the chunky “prolegs” gripping the stem. Like all insects, monarchs (caterpillars and butterflies) have six legs – but those are the “true legs”, and they’re found just behind the caterpillar’s head on its thorax. They are used for locomotion. The cylinder-shaped prolegs, on the other hand, are used to grip stems tightly as the caterpillar moves its body around. They are loosened one at a time as the caterpillar moves forward, beginning with the anal prolegs at the top in this photo . Prolegs also have a pad at the end called a crochet with tiny barbs that allow them to hook onto leaves, stems and other surfaces.

JULY 28 – Today brings a thrilling development: I spot one of the caterpillars on a wild beebalm leaf (Monarda fistulosa) conveniently adjacent to the path and it’s making the distinctive “J-shape”…..

….. that signals a chrysalis is about to emerge from that old skin, soon to be shed.

As happens with life processes (and life), it’s best to stay focused. I go inside for a few hours, thinking this will develop slowly. Not at all. When I return later, there is a beautiful green chrysalis already formed and suspended by its black “cremaster” from the monarda leaf.

This process is utterfly fascinating and fortunately someone has captured most of it with his camera. If you have a spare 10 minutes, this is a pretty cool realtime video by Jude Adamson.

JULY 29 – So now the waiting game begins. The chrysalis is so well camouflaged I eventually need a stick on the path to mark it in my monarda meadow (so called because that’s the main plant of summer, for my bumble bees.) Can you see where that yellow arrow is pointing?

AUGUST 2 – My three young grandchildren (6, 4 and 2) arrive for a holiday. I’m so excited because they’re here for 10 days and that means they should see the butterfly emerge. The 4-year old finds the chrysalis immediately.

Five days old now, it is a beautiful work of nature. Cousins, aunts, uncles and great aunts walk down my path to look at it.

AUGUST 4 – Just by chance, the 6-year old and her daddy have brought up coffee filters and instructions for making beautiful butterflies. They catch the light in the cottage window.

And then, wouldn’t you know it, we climb up the hill and at the very top in the septic bed, we find my original butterfly milkweed (the one where I photographed the monarch egg 7 years ago) with more caterpillars feeding. The leaves are already wilting from drought in our hot July, so I connect two hoses and run them up the hill to its base.

Must revive those wilting leaves for these caterpillars!

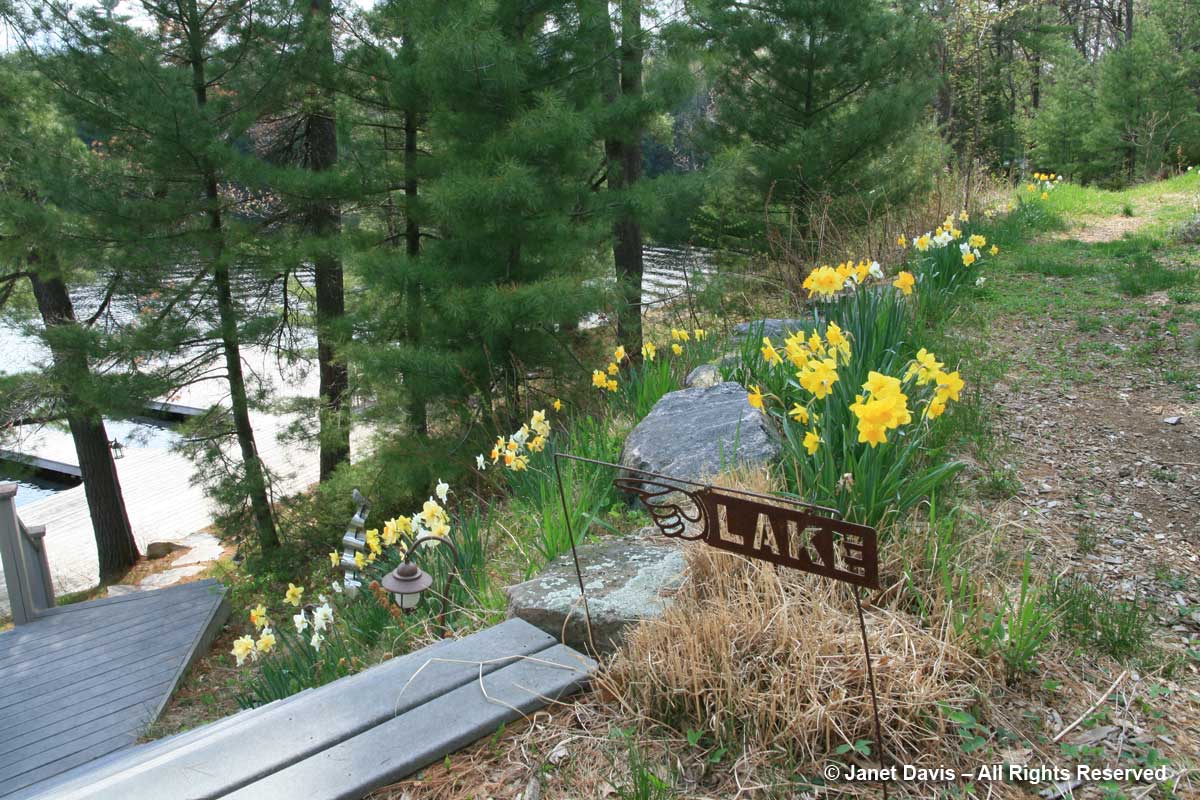

AUGUST 6 – Meanwhile, a big male monarch butterfly is seen nectaring on swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) down by the lake shore.

AUGUST 7 – The next day, he’s gracing the flowers of butterfly milkweed too. How do I know it’s a male? Because of the two paired black scent glands near the bottom of his hind wings; these are used to attract females. I’m assuming this is one of my caterpillars, since my meadows and milkweed are fairly isolated on this lake surrounded mostly by white pines, red oaks and hemlocks. There are perennial borders for nectar at a few of the neighbouring cottages, but most of the milkweed is found on the highway edges (where it hasn’t been mown down) and in old fields.

Here’s a little video I make of him the next day foraging for nectar on this milkweed, which has been growing in this spot for more than 12 years now.

Will my male still be around when his ‘siblings’ emerge? Given our latitude 45oN – the same latitude as Minneapolis – he and the pupa still in the chrysalis are part of the long-lived “migration generation” of 2019’s eastern monarch population (the western population is west of the Rockies). Unlike the other generations they exhibit delayed sexuality, so do not mate now. Provided they survive, they will leave Muskoka and fly south on an arduous, unique migration journey that I wrote about in a blog in 2014 in conjunction with the screening of a 3D film called Flight of the Butterflies. Here’s the trailer for the film, showing the oyamel firs in Mexico where this generation will roost for the winter, until they finally begin their remarkable migration north next spring and breed in Texas or near the Gulf of Mexico, before dying.

AUGUST 8 – It is raining today, but I’m keeping a close watch on “Bella”, as my 6-year old granddaughter has decided to name her. We know it’s a girl because when I lift up the monarda leaf to look at the back of the chrysalis, we see the little vertical seam near the top, as shown by the yellow arrow below. And look at the embossed butterfly shape within.

AUGUST 9 – It pours again today, making up in August for all the dry, hot days of July and making the meadow flowers very happy. The chrysalis also needs moisture, but the developing butterfly inside – called a “pupa” – is well protected from the weather. I make a video showing my meadow and its special guest in the rain.

I spend a lot of time watching the chrysalis, since the transformation to a butterfly – the “eclosure” – can happen quickly. I can just see the wings forming on the pupa inside.

AUGUST 10 – It’s my birthday! And I can’t imagine a finer gift than to watch a butterfly emerge while my grandkids watch. The cool overnight rain has caused some of the hundreds of bumble bees in my meadows to sleep in the shelter of the wild beebalm (Monarda fistulosa) flowers until temperatures warm up. I’m watching them stir to life…..

…. when suddenly I glimpse something extraordinary. All this time I’ve been watching Bella’s chrysalis, just down the path another monarch pupa has been developing in a clump of aphid-infested false oxeye daisies (Heliopsis helianthoides). It’s only because it is black in colour and transparent, meaning it’s about to eclose, that I notice it now. How exciting is this?! Can you see it?

Now I have two sites to watch. Fortunately, I have no meals to prepare on my birthday and can spend as much time as I like outdoors!

I think about the ecology of this planted meadow, where the chrysalis of a native butterfly is sharing space on a native plant with that plant’s associated native red aphids (Uroleucon obscuricaudatus). Fortunately neither insect seems bothered by the other. The photo below is at 10:50 am.

Even though I’m determined to photograph the new chrysalis as the pupa ecloses, I’ve been watching for almost 3 hours now and have a few chores to do indoors. But not having researched enough, I fail to recognize an important sign that things are starting to happen. See that little gap in the horizontal pleat, below? It means that the butterfly inside is starting to expand and push out on the chrysalis and eclosure will likely happen within the hour. This is 2:30 pm.

So I’m disappointed, but also happy when I come out at 3:38 pm to see family members on the path admiring our brand new female butterfly…..

……….hanging from her chrysalis, which has now turned white. My granddaughter names her Bianca – which seems like a lovely name for a butterfly that may well be living in Mexico in a few short months.

I settle back into my chair and, as my grandchildren come down the path to point her out to relatives and watch her find her wings, we all rejoice in this timeless last chapter of monarch metamorphosis. Watch with me for a moment.

Though I conscientiously videotape almost all of her movements as she climbs the heliopsis plant over the next two-and-a-half hours, I gaze away for a moment while deep in conversation and Bianca shivers her beautiful wings…….

….. and takes flight, landing way up in the boughs of a white pine tree as if she’s practising for the oyamel firs of Mexico.

I check quickly on Bella, but her chrysalis is still green. And then it’s time for my birthday dinner. It’s been a perfect day with the best gift I’ve ever had – witnessing one of nature’s miracles, followed by chocolate cupcakes presented to me by my famlly!

AUGUST 11 – It’s time for the grandchildren to return home and they’ve finished packing all their important possessions. After lunch, they drive off with mommy and daddy.

Meanwhile, out in the breezy meadow, I sit and watch. A clearwing hummingbird moth (Hemaris thysbe) darts from beebalm to beebalm.

An uncommon bumble bee (Bombus perplexus) nectars in the blossoms.

Bella’s chrysalis is turning darker. That means she should eclose within 48 hours. Will today be the day? I set up my camera on the tripod and make this video at 6:26 pm.

AUGUST 12 – By the time I go out to the path the next morning at 7:40 am, the distinctive expansion of the horizontal pleat on Bella’s chrysalis has begun. It is her 13th day in the pupal stage. I set my camera to video mode and wait. An hour later, it begins. The video below compresses an 8-minute period into less than a minute. I am fascinated by her strenuous efforts to use her forelegs as anchors to push out of the chrysalis. In a strange way, it reminds me of all the physical effort of the labour that precedes childbirth. Alas, since I’m new at this eclosure watch, I only realize near the end that my lens is too closely focused on the chrysalis; when Bella emerges, she falls out of my frame. Fortunately, she hangs onto the very tip of the beebalm leaf and I quickly adjust my lens.

Having missed Bianca’s eclosure, I’m thrilled to have witnessed Bella emerging. I keep my camera focused on her and note the drop of meconium suspended through her anal opening. This is the waste product from her weeks in the chrysalis.

She hangs her wings to dry them, with lots of room in the meadow to manoeuvre. Some newly-eclosed butterflies are said to injure themselves when they cannot fully stretch their wings. The next step is to pump her wings full of liquid to expand them prior to flying.

Then I wait and watch. I sit in the path reading my book, checking my emails from time to time, but mostly staring at this tiny little creature, willing it to fly.

For more than eight hours I wait and watch, keeping her in my viewfinder. I check the internet to see how long it might be before a young monarch finds her wings. Two hours is the average, maybe a little more. I give her all the benefit of doubt; we have waited so long to see her. Blue jays and song sparrows call from the pines, cicadas drone noisily and train whistles echo beyond the forest. I watch Bella try repeatedly to pump her little wings open, but she fails. The video below captures almost nine hours in less than 2 minutes.

Bella is shrivelling up now. She’s just a little insect, a tiny speck in the universe, but I am devastated.

Some of my friends have raised monarchs in captivity, carefully monitoring the various stages and releasing them safely after they eclose. My friend Kylee Baumle wrote a popular book called The Monarch: Saving Our Most-Loved Butterfly.

Carol Pasternak, the “Monarch Crusader”, wrote a book called How to Raise Monarchs: A Step by Step Guide for Kids.

Bella was to have been an experience in the wild, in our very own meadow, but unlike Bianca she paid the heavy cost levied by mother nature. It’s estimated that more than 90 percent of monarch butterflies fail to survive in the wild. I search online for the most compassionate way to end her short life. Then I remove her gently from the beebalm leaf and hold her on my hand. I feel her little feet tickling my palm. I thank her for letting us watch. And I cry buckets of tears that I realize are not all for Bella, but for the sad things that happen in everyone’s life at some point, the things we fail to properly mourn.

When I began this blog, it was going to be a celebration of the birth (or eclosure) of the first monarch butterfly I’d ever seen form a chrysalis. It didn’t turn out that way, but it was a fascinating journey nonetheless – and a lesson that nature can be harsh and survival isn’t assured with beautiful, much-loved insects, any more than it is with other animals on this planet. Thank you Bianca, and thank you most especially little Bella.

*********

If you liked this litle rumination on monarchs, please leave me a comment. I’d love to hear about your own experiences.