It was our fourth day in Nunavut cruising aboard the MV Sea Adventurer. After our initial visits to Iqaluit and Pangnirtung, we were now heading towards Cape Dyer, which in a few days would be roughly our departure point across the Davis Strait to Sisimiut, Greenland.

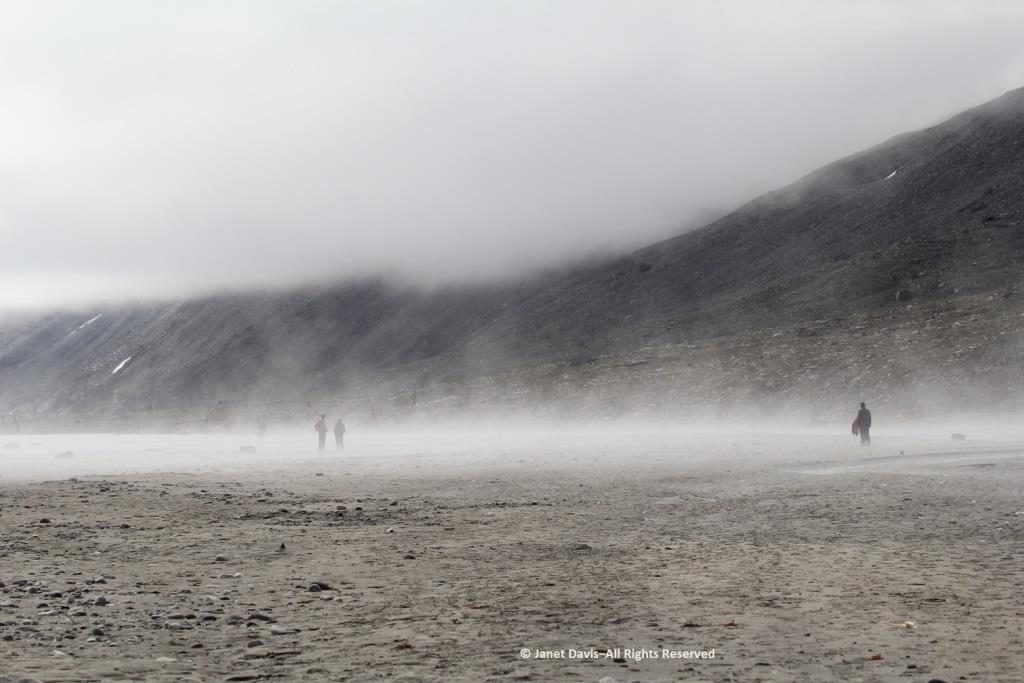

Fog blanketed the Arctic, which meant, for the captain, it was slow going.

In the lounge, Heidi Langille, who resides in Canada’s capital city Ottawa, gave an afternoon lecture on what it was like to be an “urban Inuit”.

That evening after dinner, there was music on deck and Heidi and our other Inuit cultural emissaries demonstrated some traditional games of strength…..

….. while we cheered them on.

The next morning, the sun was warm on the east coast of Baffin Island as we made our way up the appropriately-named Sunneshine Fjord – also seen as Sunshine Fiord in some references….

….and dropped anchor.

The zodiacs ferried us to a wet landing on shore. It’s interesting that, if you’re a resource staffer on an Adventure Canada expedition, you must also know how to captain a zodiac. That goes for (now retired) art and culture director Carol Heppenstall, standing in the blue life-vest to the left of (now retired) expedition leader Stefan Kindberg.

When you land on an unoccupied shoreline in Nunavut, there’s a good chance that even though there are no human occupants, there may well be polar bears. Thus, our expedition leader Stefan Kindberg carried both a handgun and rifle. Fortunately, he’s never had to use them, and commented dryly: “You don’t ever want to have to shoot a polar bear in Canada. Too much paperwork!”

We were invited to explore the landing area. We could stay on the beach, work our way around the lower slopes, or climb right to the top.

My husband Doug (below) elected to stick near the shore. I was happy we’d purchased new walking poles….

….and, again, I was delighted with my new rubber boots. Wearing them, I was able to shake up a lot of green algae in the shallow water of this intertidal zone.

I loved looking at the seaweed. So many different species….

….. each with its own ecological community….

….. and adapted to the seasonal mix of salt and fresh glacial meltwater in the fjord.

Some of our group elected to climb to the summit, but I was most anxious to botanize on the lower slope.

This part of Sunneshine Fjord was a perfect place to be. The moraines were gently sloped, the sandy beach quite wide, the fjord deep enough for our ship, and these slopes – so monotonously featureless and olive-brown as the ship sails past them – were absolutely brimming with plant life.

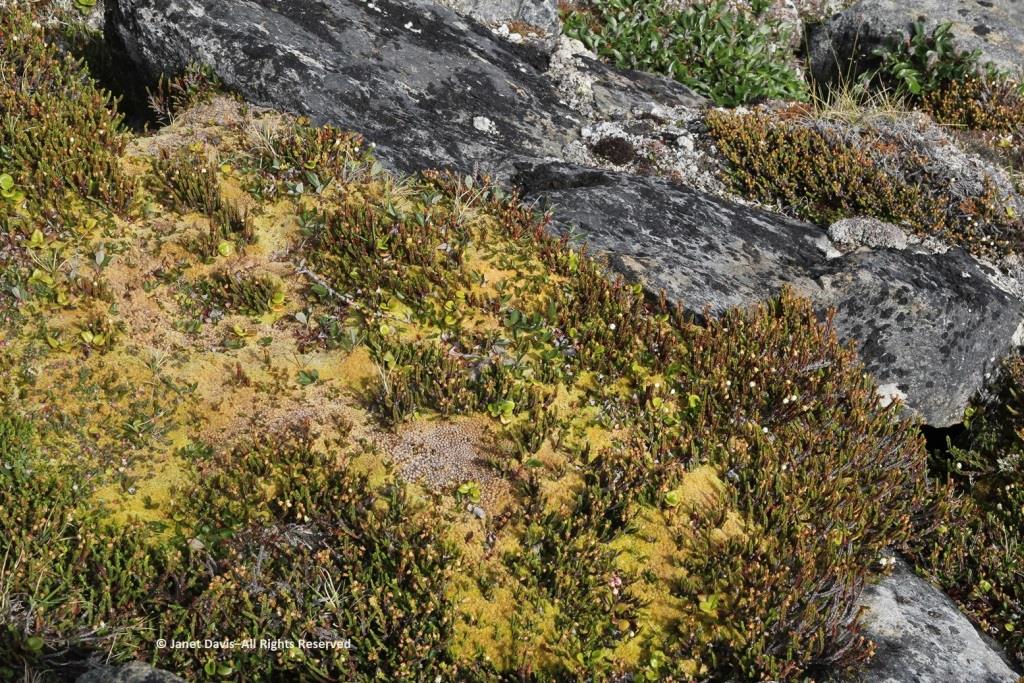

Unless you get closer, you might not guess that those lighter areas on this hillside….

…… are colonies of mountain avens (Dryas integrifolia) wreathed in creeping willow shrubs.

Or that these paler drifts….

…… are Arctic heather (Cassiope tetragona), sometimes punctuated with hairy lousewort (Pedicularis hirsuta).

Here’s a closer look at hairy lousewort to illustrate the trait that earned its name.

Morning dew was still on this pair of natives: Arctic harebell (Campanula uniflora) with large-flowered wintergreen (Pyrola grandiflora).

Arctic cinquefoil (Potentilla hyparctica) is a circumpolar species, also native to Alaska, the Yukon and Norway’s Svalbard archipelago.

Arctic blueberry or bilberry (Vaccinium uliginosum) would bear its fruit in August – with only birds and small mammals to appreciate it.

A butterfly was nectaring on moss campion (Silene acaulis).

Arctic poppies (Papaver spp.) were in flower….

….. and dwarf fireweed (Chamerion latifolium), too.

Moss had colonized the rocky outcrops in the damper areas.

There was runoff from the small glaciers beyond the summit. Though Sunneshine Fjord is not directly related to Baffin Island’s Penny Ice Cap, it has (like all parts of the Arctic) drainage from abundant snow and ice on the upper elevations.

Here we see Arctic willow (Salix arctica) clinging to a boulder beside the waterfall.

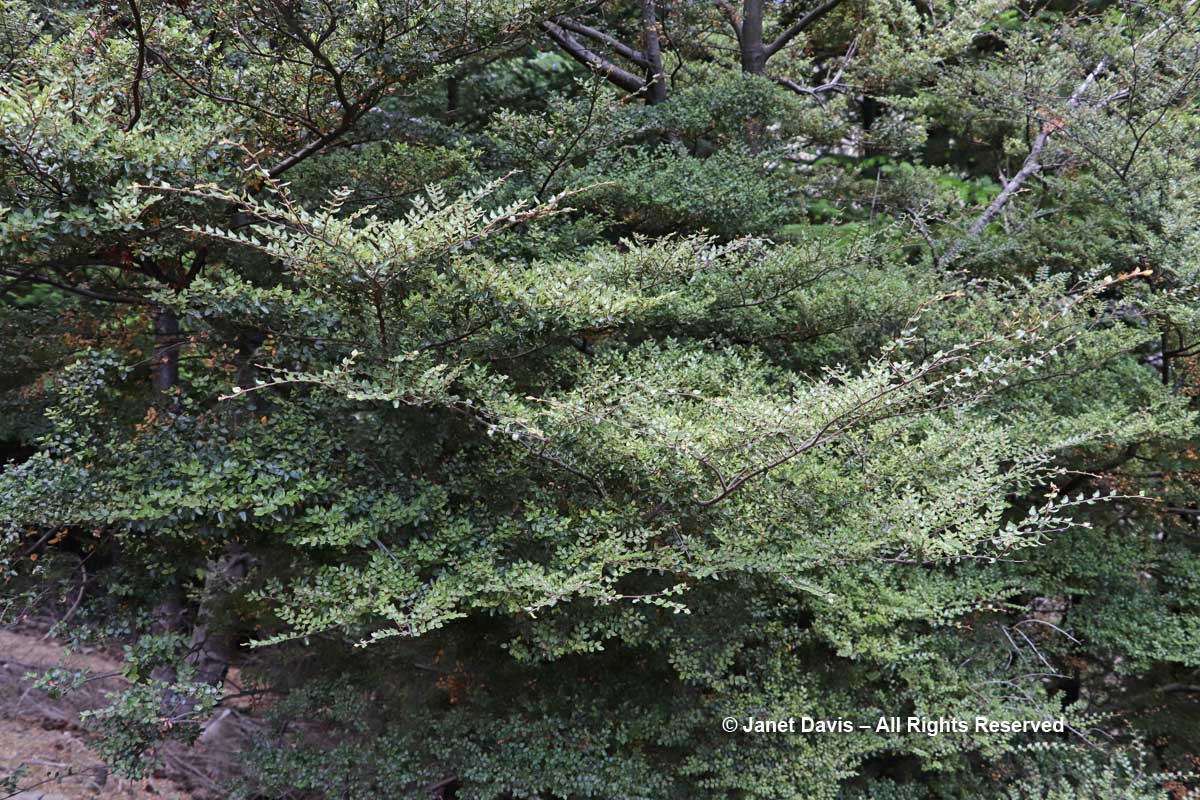

Arctic willow grew everywhere on our expedition. One of thirteen species native to Nunavut, it grows farther north than any of the other willows and is the most common willow on Arctic islands. Usually prostrate, it can also change its growth habit in certain circumstances and become erect, with a height up to 1 metre (3 feet). Its hairy leaf reverse is a distinguishing characteristic, versus the similar-looking northern willow (Salix arctophila), which has glabrous or smooth leaves. It can be very long-lived, with a Greenland specimen dated to 236 years. Its leaves are edible and Inuit people traditionally peeled and chewed the roots of this plant they call suputiksaliit to relieve toothache – recalling the general pharmaceutical use of salicylic acid derived originally from certain Salix species as aspirin (now made synthetically). When Arctic willow seeds ripen, they are surrounded by fluffy hairs (willow cotton) that help them disperse on the wind.

I spotted some bearberry willow (Salix uva-ursi) as well, but I was most interested in the beautiful black lichen on this rock, sensibly called black lichen (Pseudephebe minuscula, formerly Alectoria).

Here you can see how black lichen develops and grows. The study of the growth rate of lichens, by the way, is called lichenometry.

Some of the resource personnel were capturing the scene on the lower slope. This is Kenneth Lister, now retired as a curator of Arctic anthropology at the Royal Ontario Museum.

Dennis Minty, below, is a well-known photographer on many Adventure Canada expeditions.

It was challenging to walk back to the beach through the glacial debris field.

This cobble sandbar jutting out from the beach was raised enough that I was able to make our ship look like it was sinking.

The air on the last day of July was quite warm and wisps of advection fog came and went above the cold Arctic waters.

Walking back to the beach where the zodiacs waited, I was fascinated by the stunning rock formation below, exposed by the ocean waves (and perhaps glacial ice?) along the fjord. It was beautiful and mysterious. Until this week, I hadn’t made a serious effort to discover more. This is, after all, a very isolated part of Nunavut: perhaps some Inuit fishermen come in here, the odd scientific expedition, and a handful of summer adventure cruises over the decades,(sea ice and weather willing).

The rocks, though fractured, were beautifully banded, similar to the banded gneiss, below, that I love photographing on the highway near our cottage on Lake Muskoka north of Toronto. A Precambrian rock, it is part of the Grenville Province (Muskoka Domain, Moon River Lobe) and is dated to about 1.4 billion years before the present, i.e. the Paleoproterozoic Eon (literally “before animals”).

Could my Sunneshine Fjord rocks be that old? I reached out via email to some geologists whose names I found online associated with the Cumberland Peninsula or Cape Dyer just north of the fjord. At one time during the Cold War between the west and Russia (1958-92), Cape Dyer was a radar station and part of the DEW Line, the Distant Early Warning System. Today it’s one of 40 sites across the north that has had to be cleaned up (at a cost of $575 million) to get rid of contaminated soil, fuel tanks and other debris.

I received a nice email in response from Dr. John T. Andrews, Professor Emeritus and Senior Fellow with the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research at the University of Colorado. He had done glacial/climate change research near Cape Dyer and wasn’t sure about my rock, but kindly sent me the abstract for another geologist’s paper on the region’s volcanic history. “This paper describes the field relations of Tertiary basalts which are preserved as small patches intermittently along the coast for 90 km northwest from Cape Dyer, Baffin Island. The flat-lying, subaerial lavas generally rest directly on the Precambrian basement but in some localities a thin sequence of terrestrial sediments intervenes between the basement and the volcanics. Where the sediments occur, the overlying volcanics tend to be divisible into a lower unit of subaqueous volcanic breccia and an upper sequence of subaerial flows. In age, stratigraphic position and magma-type, these volcanics strongly resemble those of the basalt province of west Greenland. A model is presented for the generation of both provinces in a single volcanic episode, related to the opening of Labrador Sea – Baffin Bay by continental drift.”

Wow! A volcanic episode had ruptured Greenland from Baffin Island? I suppose I should have studied up on the basic tectonic relationships of the Eastern Arctic before going further. But my banded rocks in Sunneshine Fjord didn’t look like the columnar basalt formations from the Columbia River Basalt Flood, below, that I had photographed in northeast Oregon two years ago and written about in my blog on Oregon’s Thomas Condon Paleontology Center.

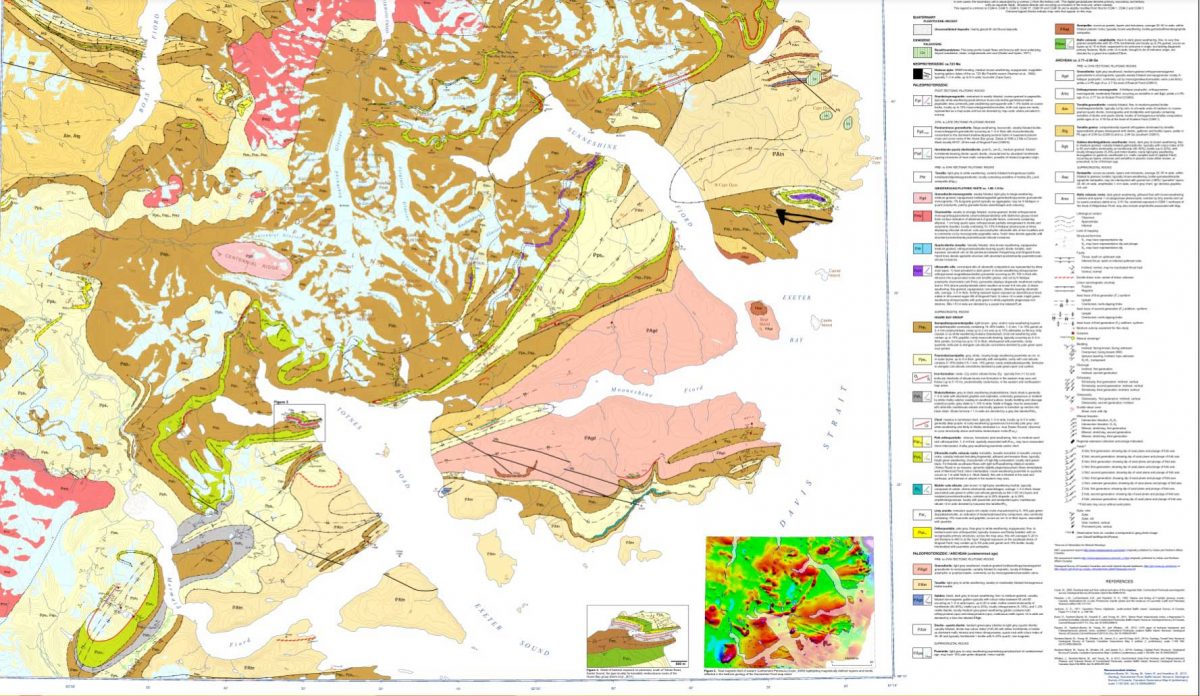

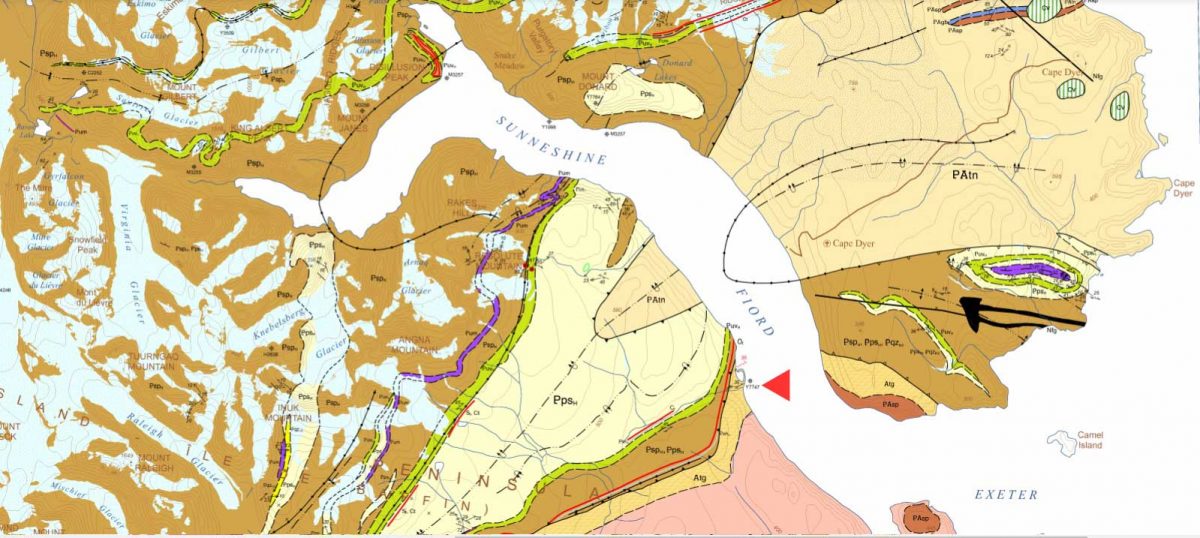

After a few days of searching on Google, I must have put in some magical search parameters (fiord, not fjord, etc.) and came up with a Research Canada page containing a full geological map of the area around Sunneshine Fjord, below!

When I enlarged the map, I thought I could spot the exact area with the cobble sandbar that we had visited, marked with a red arrow below!

The lead author was geologist Dr. Mary Sanborn-Barrie. I sent off an email with photos of my rocks, but didn’t hear anything back right away. Maybe she was in the field, out of wifi range, dubious about such a random email from someone she didn’t know? But then I received a reply from her and it made me so happy. Because my rocks were old, really really old!

Hi Janet

What a beautiful exposure of rocks you were able to explore on the shoreline. Our mode of transport was helicopter drop-off and then walking all day, so we rarely (if ever) got to map such gorgeous wave-washed exposures.

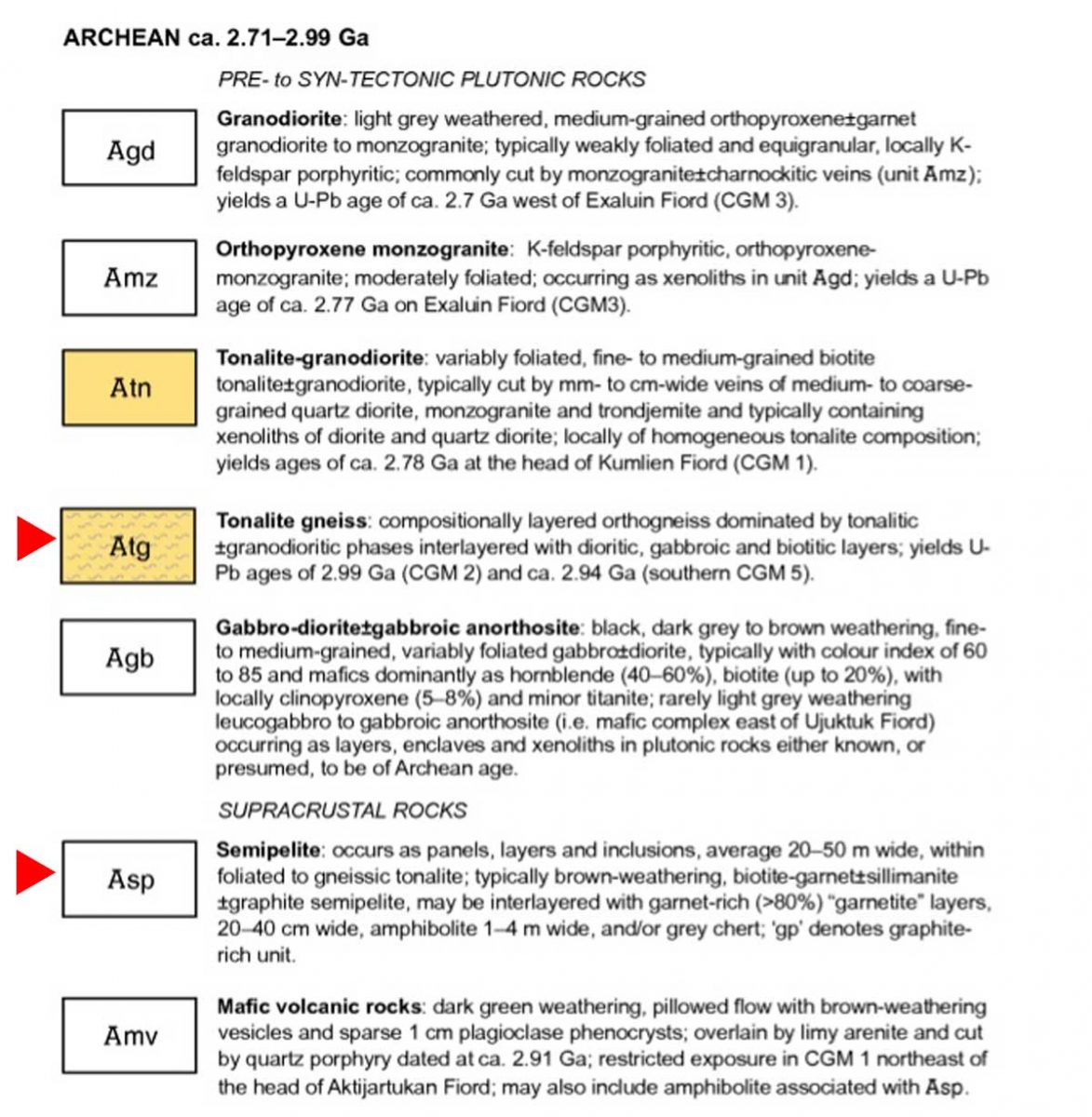

Actually your photographs appear to be of the oldest rocks in the region, rather than the youngest! They appear representative of the deformed and layered Archean (A) tonalite gneiss (tg) basement (unit Atg in the legend below) that underlies much of Cumberland Peninsula and which is dated at two localities at 2,990 million years old and 2,940 million years old. The pale grey layers are foliated tonalite and any biotitic and/or mica-rich layers (unit Asp in the legend below) are likely even older sediments that were intruded by the tonalite. Upon closer inspection, such mica-rich may also contain garnet and/or silky silvery sillimanite – both minerals diagnostic of high-alumina sedimentary rocks.

Here’s an enlargement of the legend to which she referred:

I was so happy I’d made closeup images of the rock layers, below. Imagine! These Archean rocks at 2.99 – 2.94 Ga (Giga annum or billion years) are twice as old as the rocks on the highway near my cottage, from an eon whose name comes from the same root as “archaic” stretching back 4 billion years.

I had photographed the upper slope from the beach, below, and all I could see was more of the same, but there were, in fact, some much younger rocks in places at the top of the cliffs on Sunneshine Fjord. Dr. Sanborn-Barrie included information about those rocks as well, as she continued in her email (below my photo).

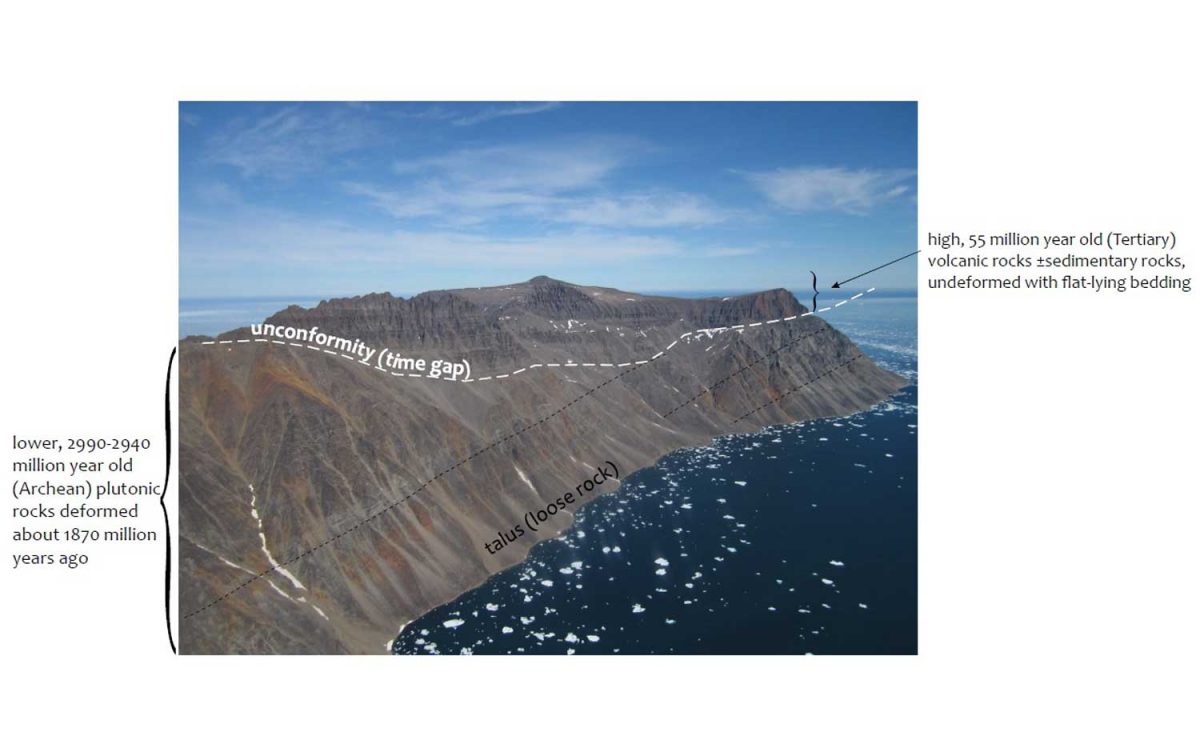

“These tectonically layered rocks (as opposed to the bedded (primary layering=strata) observed in the Tertiary sequence) underlie (that is, they are low on the cliffs) the much younger, unconformably overlying Tertiary basalts that erupted about 60-55 million years ago during spreading of the Baffin basin.“ She also enclosed a photo of herself examining those overlying Tertiary basalts with a view across the fjord to basalts atop the ancient rock.

And she provided an info-card using a photo from Sunneshine Fjord showing what is meant in geology by “unconformably” or “unconformity” (n.): meaning “a series of younger strata that do not succeed the underlying older rocks in age or in parallel position, as a result of a long period of erosion or nondeposition.” Thus, we don’t know what happenened here between 2.9 Ga and 60-55 Ma because all the physical evidence for that vast period has disappeared. That break in the record is called a “hiatus”.

Returning now to that wonderful last day of July in 2013, it was time for us to climb into the zodiacs, board the ship and take our leave of Sunneshine Fjord.

It was so warm outdoors that a barbecue lunch was served on the rear deck……

…… complete with grilled chicken and steak.

Passing an iceberg…..

…..we bade farewell to the coast of Baffin Island, Nunavut and Canada.

Hours later, I was happy I hadn’t consumed too much wine at that lovely lunch because I was flat on my back in my bunk, having taken a motion sickness pill and given up on trying to read. Every now and again, I’d pull myself up to look out the window at the 9-foot swells that had the ship rocking back and forth like a slow amusement ride… for hours and hours. My husband, who doesn’t get seasick, returned from dinner and announced cheerily: “Well, you’re in the majority! And some people left the dining room in a big hurry!” I groaned and closed my eyes and thought of a young Charles Darwin, often seasick in his hammock on his five-year voyage aboard The Beagle. “I hate every wave of the ocean, with a fervor,” he wrote to a cousin in 1835.

Fortunately, morning did come, the seas calmed, and we arrived on a sunny August 1st on the west coast of Greenland. Coming up in my next blog: Sisimiut.