It was with great joy that I stepped into Chicago’s Lurie Garden last August. It didn’t matter that my companions numbered in the hundreds (garden communicators from all over North America at the annual Gardencomm symposium) – as long as they didn’t get in my shot! And it was the perfect time to visit, with the Lurie evoking in a romantic, chaotic way the wildflower-spangled prairie that once stretched across sixty one percent of Illinois (21.6 million acres), before the arrival in the 1830s of homesteaders and the John Deere tractor that broke up the tallgrass sod to plant beans and barley. No, the Lurie Garden is not a prairie recreation, and it’s certainly not ‘country’, given that it occupies five leafy acres of 24.5-acre Millennium Park in the heart of downtown, framed by some of the tallest skyscrapers in North America.

But when you see the artful tumble of some of the tallgrass prairie’s iconic natives, such as spiky rattlesnake master (Eryngium yuccifolium)….

…. and towering yellow compass plant (Silphium laciniatum), its common name alluding to the belief of pioneers that its leaves always pointed north and south,…..

…… mixed with other perennials and lush ornamental grasses in the Meadow section of the garden nearest Monroe Street, it certainly feels like walking into an August prairie in the middle of the city.

It was spring 1914 when poet Carl Sandburg wrote his ode to Chicago.

Hog Butcher for the World,

Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat,

Player with Railroads and the Nation’s Freight Handler;

Stormy, husky, brawling,

City of the Big Shoulders

And it was the last line of that first verse and the nickname it lent Chicago – City of Big Shoulders – that landscape architects Gustafson Guthrie Nichol lit on in the late 1990s when they conceptualized the space that would become the Lurie Garden. Those “big shoulders” became the 15-foot high shoulder hedge, an L-shaped living wall separating the garden from the busy footpath to the Frank Gehry-designed Jay Pritzker Music Pavilion (see the steel roof angles) and Great Lawn in the space beyond.

Comprised of five cultivars of arborvitae (Thuja occidentalis) and hedge-friendly hornbeam (Carpinus betulus ‘Fastigiata’) and European beech (Fagus sylvatica), the shoulder hedge also echoes those other big shoulders of the towering skyscrapers behind Millennium Park. By the way, that’s a cultivar of white-flowered prairie native Culver’s root (Veronicastrum virginicum) in the foreground with a purple cloud of sea lavender (Limonium latifolium) nearby.

For Dutch superstar designer Piet Oudolf, the Lurie plant design was his first commission in the U.S. and his first big public garden, though later he would design the plantings for the High Line in New York (which I blogged about in June 2014), our own entry border at the Toronto Botanical Garden (which I blogged about in March 2017 including the intricate design nuts-and-bolts) and the Delaware Botanic Gardens at Pepper Creek (opening this September), among others. When he became the perennial plant designer of the winning Lurie design team under Seattle-based landscape architects Gustafson Guthrie Nichol Ltd. (GGN) at the turn of the millennium and had his plant list prepared, he travelled to Chicago to meet with nurseryman Roy Diblik, owner of Northwind Perennial Farm in nearby Burlington, Wisconsin. Roy had already read Gardening with Grasses, the book Piet co-authored with Michael King in 1998, one of many design books he has written; it astonished him. As he said in a 2016 interview on The Native Plant Podcast, “It was the first book I’ve ever seen about grasses intermingled with other plants. This book showed communities, how to interplant, playfulness. It was wonderful.”

Roy Diblik, below left, recalls their first meeting in the biographical Oudolf Hummelo – A Journey Through a Plantsman’s Life (2015 ) by Piet Oudolf and Noel Kingsbury: “I remember how he rolled out a copy of a plan for the Lurie Garden on a workbench. I could see immediately that there had never been anything like this before in the Midwest. We went through the plants, what would work, and not work. He got me involved in producing the plants – 28,000 plants, with no substitutes. We subcontracted the growing of the easier plants and I did the more difficult ones myself.” For his part, Piet had never seen a prairie before and Roy loved the prairie and its plants deeply, so he took his Dutch visitor to visit the Schulenberg Prairie at the Morton Arboretum, a very moving experience for Piet. So it was natural that they became more than design collaborators; they became close friends. The professional collaboration continues today, since every two years the Lurie invites them and the landscape architects to visit the garden, inspect the plants and assess how they’re performing……

…… in a consultation that includes Director/Head Horticulturist Laura Ekasetya, below, part of the formidable all-woman team at the Lurie.

To place the Lurie in context, you can see below in this amazing July image by Devon Loerop Media the Seam, the Light Plate and Dark Plate and beyond the garden, people sitting on the Great Lawn enjoying a performance at the Pritzker Pavilion under the airy overhead trellis containing the sound system.

Looking the other way in another image by Devon Loerop Media, you see Renzo Piano’s beautiful Modern Wing of the Chicago Art Institute, whose windows look directly onto the undulating garden, its sloping, prairie-like meadow and gardens and trees like some ever-changing work of modern art.

On a hot day last August, just beyond the bee-buzzy cloud of white calamint (Calamintha nepeta), there were young visitors cooling their feet in the water course, just out of view, that bisects the Lurie as part of the “Seam”, GGN’s evocative separation of the garden into the Light and Dark Plates. The Light Plate, left, is the sunny prairie-like side; the Dark Plate features a more garden-inspired design with many plants growing in dappled shade under black locust trees (Robinia pseudoacacia). In between on the Dark Plate side is an area called the Transition Zone, with tall plants.

The water course is part of stepped pools underlying the broad ipe wood walkway that carries visitors through the garden. But what exactly did the landscape architects intend to evoke with the Seam? Most of the waders would not understand that this is a sophisticated means of connecting the Lurie with the underlying landscape.

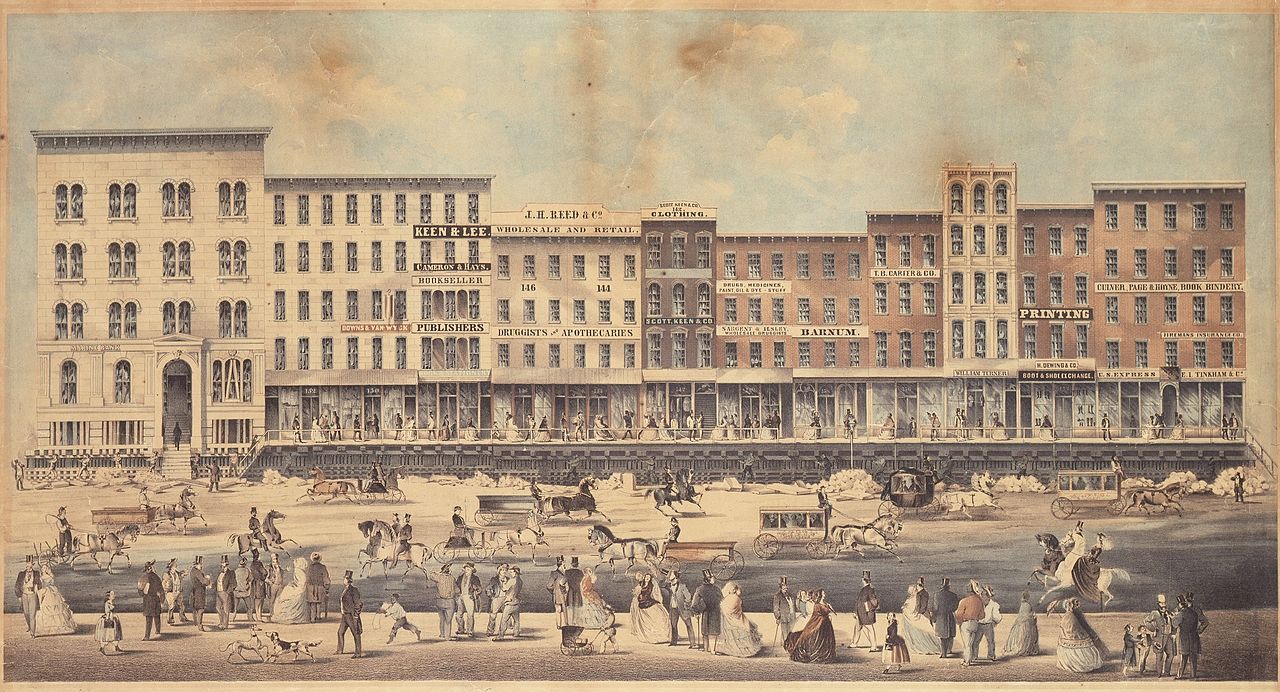

Not the immense parking garage immediately below – since Millennium Park is a massive green roof, the largest in the world. Not the ghost of the old Illinois Central Railway tracks below. Rather, it evokes the swampy marshland in the delta of the Chicago River that once led into Lake Michigan just a few blocks away, atop which young Chicago grew in the early 19th century. By 1900, the river would be reversed to flow ultimately into the Mississippi River, but it was a muddy beginning for the young city that necessitated a gigantic engineering project and wooden walkways to ensure that the big-shouldered city and its citizens did not sink into the mire. That’s the history conjured up by The Seam.

The Raising of Chicago was undertaken after outbreaks of cholera in 1854 and ’59 killed more than two thousand people. It involved the use of jackscrews to lift entire streets of buildings six feet above ground. Below is an artist’s 1856 rendering of the plan to raise Lake Street. Connecting historic events like this with a contemporary landscape like the Lurie is perhaps the finest interpretation of capturing a ‘sense of place’. Read more about Gustafson Guthrie Nichol’s design rationale for the Light and Dark Plates and the Seam here.

The plants for the wildish front section of the Lurie may evoke the prairie, but Piet prefers to call this the Meadow. As Noel Kingsburgy wrote in Oudolf Hummelo: “At the time Piet created the Lurie Garden, it represented a new level of complexity and sophistication in his design. It drew on a number of elements that had proved successful elsewhere, but it also contained several innovations. The bulk of the planting is formed of like plants clumped together, although there is a small area of innovative intermingled planting at the southern end, known as The Meadow, where species are mixed in a truly naturalistic fashion. Its matrix of ornamental grasses including the native Sporobolus heterolepis, is broken at intervals by a number of perennial species that rise up above the grasses….” The matrix system would inspire Piet a few years later in his design for the High Line. Many of the plants in the Meadow are native prairie plants, but not all. The lovely white coneflower below is Echinacea ‘Virgin’, one of Piet Oudolf’s own introductions.

Grasses are chosen for their hardiness, beauty and architectural durability, regardless of whether they’re native species, non-natives or selected cultivars. Here is the Meadow’s matrix grass, the lovely tallgrass native prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis).

Award-winning ‘Blonde Ambition’ blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), below, has striking pennant-like flowers and grassy, blue-gray foliage.

Autumn moor grass (Sesleria autumnalis), on the other hand, is a European grass that Piet knew well from previous designs. In June, it’s the soft, chartreuse framework for the Lurie’s spectacular purple-blue “salvia river”, and in summer, it enhances purple coneflowers and cloudlike, white-flowered prairie spurge (Euphorbia corollata).

Here is autumn moor grass nestling the tallgrass prairie forb wild petunia (Ruellia humilis).

Grasses also frame another typical prairie denizen, nodding onion (Allium cernuum).

‘Karl Foerster’ feather reed grass (Calamagrostis x acutiflora) may be the most commonly-seen ornamental grass in North America now, but it creates the perfect vertical accent below. It is named for the renowned Germany nurseryman and plant breeder Karl Foerster (1874-1970) who in turn was the teacher of Piet’s own friend, the late nurseryman and plant breeder Ernst Pagels (1913-2007). Pagels introduced many plants we see in Oudolf gardens, including Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’ ‘Blauhügel’ and other sages; Phlomis tuberosa ‘Amazone’; Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Diane; Astilbe chinensis var. taquetii ‘Purpurlanze’; and, in honour of Piet, award-winning Stachys officinalis ‘Hummelo’.

One of the paradoxes of the surge in popularity of American native plants and their selections is that much of the work was done in Germany and Holland. ‘Shenandoah’ switch grass (Panicum virgatum), below, with its rich red foliage, was selected by another of Piet’s friends, German plantsman Hans Simon. Here it is with the ferny foliage of Arkansas bluestar (Amsonia hubrichtii) and Agastache ‘Blue Fortune’, a superb hybrid of North American anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) and Korean Agastache rugosa, bred and selected by Gert Fortgens at Rotterdam’s Arboretum Trompenberg.

The ‘Blue Fortune’ anise hyssop was attracting hordes of monarch butterflies the day I was there, and the photographers in the crowd were vying for the perfect shot.

Pennisetum alopecuroides ‘Cassian’ is an excellent, hardy fountain grass named for Piet’s friend, Cassian Schmidt, director of the renowned German garden Hermannshof.

A signature plant in Piet’s gardens is airy sea lavender (Limonium latifolium), seen here with a tiny sprig of prairie spurge (Euphorbia corollata).

Nearby was a drift of early-blooming pale purple coneflower (Echinacea pallida), their pink flowers now bronzed with age. Seedheads and senescing plants, of course, are a vital part of the four-season design that Piet has promoted in his gardens, adding structure to plantings and an evocative, almost metaphorically human sense of “a life well lived” . As he told a New York Times writer more than a decade ago: “You accept death. You don’t take the plants out, because they still look good. And brown is also a color.”

The seedheads of Allium lusitanicum ‘Summer Beauty’, a Roy Diblik plant introduction, still looked wonderful, especially framing Echinacea ‘Pixie Meadowbrite’.

Wild quinine (Parthenium integrifolium) is a tallgrass prairie perennial whose flowerheads were slowly turning tawny.

Under the trees in the Dark Plate, the brown seedheads of Phlomis tuberosa ‘Amazone’ added a strong note of verticality.

Touring visitors through the Lurie, as Laura Ekasetya was doing here, often means explaining Piet’s philosophy, since people don’t always appreciate the beauty of plants once the flowers fade. Birds do, of course, and seeds of many perennials offer nourishment to songbirds long after summer ends.

And even without their purple flowers, the tall spikes of prairie blazing star (Liatris pycnostachya) are simply spectacular, and will be prominent well into winter.

But the liatris season is long, and the knobby flowers of rough blazing star (Liatris aspera) were just opening……

….. bringing native insects to nectar. This is the two-spotted longhorn bee.

The Lurie attracts a diverse roster of insects to forage on the flowers. Native skullcap (Scutellaria incana) was being visited by a lumbering carpenter bee (Xylocopa virginica), while…..

….. tall ‘Gateway’ Joe Pye weed (Eutrochium maculatum) was entertaining monarchs, as was….

….. the ‘Diane’ Culver’s root (Veronicastrum virginicum).

In fact, monarch butterflies were even mating on the common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) that had been left in a few spots in the garden to ensure enough food for the monarch’s larval caterpillars.

Although I’m a prairie girl at heart, I finally dragged myself away from the sunny Light Plate into the shade-dappled Dark Plate. Here, the planting is less meadow-like and more refined, much as you would find in garden borders.

And I loved the chickadees that were flitting through the trees. Here’s a little taste….

The perennials in this section appreciate richer soil and a little more moisture, too. Below is Heuchera villosa ‘Autumn Bride’ with Aruncus ‘Horatio’ having formed seedheads behind. Pink Japanese anemones are at the rear.

I could smell the perfume of the summer phlox (Phlox paniculata) even before I arrived at the spot where it was flowering. In every possible shade of pink, it was paired perfectly with Joe Pye weed (Eutrochium spp.).

Great blue lobelia (Lobelia siphilitica) made a good companion to the phlox. Summer phlox is one of those native North American perennials that enjoyed early cosmopolitan success in the 18th century when plants were collected in the “new world” and shipped to Europe. It was John Bartram who found it growing near Pennsylvania’s Brandywine River in 1732, and sent it to England, where it soon found its way into estate borders and cottage gardens throughout Europe. Though it is occasionally susceptible to disease (and voracious groundhogs in my own Toronto garden, where I haven’t seen a bloom in years), it is such a lovely mid-late summer perennial and romantically ebullient and perfumed.

In fact, it was in this part of the garden where Piet Oudolf and Roy Diblik noticed a phlox, below, that had seeded from the original planting of a named variety. It was clear pink and exhibited excellent characteristics. After watching it for a few years, they had it dug up in 2016 and taken to Brent Horvath of Instrinsic Perennial Gardens (IPG) in nearby Hebron, one of the midwest’s finest wholesale perennial growers. In honour of the Lurie’s Director and Head Horticulturist, Piet named it ‘Sweet Laura.’ And as Laura Ekasetya says, “He is including this plant in the new edition of (his book) Dream Plants for the Natural Garden.” IPG propagated cuttings in 2017 and 2018 and it is now sold locally and at the Lurie Garden’s May plant sale.

As I was reluctantly leaving the garden to return to the symposium at the over-air-conditioned convention centre, I saw a honey bee landing on Geranium soboliferum, Japanese cranebill, below. It cheered me up as I was planning to return on my own later that day to meet someone special at the Lurie.

IT WAS 2011 WHEN I proposed a story on urban beekeeping to Organic Gardening magazine, which has sadly since folded. The story featured three expert beekeepers and their shared wisdom about the ancient art and science of beekeeping. One was Michael Thompson, beekeeper for the hives on the rooftop of Chicago City Hall and also the Lurie Garden. But beekeeping (read this Edible Chicago article on Michael and his history with honey bees) and being co-founder and director of the Chicago Honey Co-op is just one of Michael’s journeys in life; he also works with urban agriculture (including an urban orchard project), especially in parts of the city where organically-grown vegetables and neighbourhood involvement are a departure from the norm. When I was making my plans to travel to Chicago, I contacted Michael to ask if there was a chance we could meet in person. We agreed on a time and I made my way back to the Lurie that afternoon. After arriving on his bike in sweltering temperatures, Michael donned his veil and began inspecting the hives.

Brood and honey looked good for August, a product of the Lurie’s abundance of nectar- and pollen-rich plants (not to mention urban street trees throughout Grant Park and downtown).

Among the plants I’d noticed earlier with honey bees were Japanese anemones (pollen only, which bumble bees also collect)….

…. Knautia macedonica, which yields magenta-pink pollen…..

…. Culver’s root (Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Diane’), which is a superb plant for native pollinators too….

…. calamint (Nepeta calamintha), which honey bees adore…..

…. and mountain mint (Pycnanthemum muticum), which attracts honey bees and other pollinators in droves.

But apart from seeing the beehive inspection, I wanted to meet Michael in the flesh here at the Lurie, to cement one more personal connection in this wonderful world of flora that we all cherish.

And after receiving my gift of Chicago Co-op honey….

…I went back into the Lurie, now comparatively empty of people. And I thought of the friends I was with on this symposium, people I’ve come to know in the thirty years I’ve been immersed in gardens, like Helen Battersby, who co-produces with her sister an award-winning blog called Toronto Gardens…..

…. and Washington state photographer Mark Turner, who has captured with his lens every native plant in his beautiful part of the world….

….. and Theresa Forte, who writes a column for the St. Catharine’s Standard (and is a proud grandmother like me). Behind her is Portlander Kate Bryant, who generously drove me around her fair city visiting gardens last year, not long after our Lurie visit.

I’d shared a Lurie stone wall at lunch with horticulturist Anne Marie Van Nest, a longtime friend who gardens at Niagara Parks and Quebec’s Larry Hodgson, who writes, photographs and leads tours en Français to gardens throughout the world.

I thought of the people who grow all the plants and tend all the gardens, like Intrinsic’s Brent Horvath and his partner, Chicago Botanic Garden’s Lisa Hilgenberg, who manages the edible gardens there. I would meet them at the symposium dinner later that week.

And I thought of people directly related to this very garden’s design ethos, and a fun dinner in 2016 hosted by the New Perennialist himself, Tony Spencer, standing left, with me, plantsman David Leeman, special guest Roy Diblik and nurseryman Jeff Mason of Mason House Gardens. Tony also began the Facebook group Dutch Dreams, and has become a good friend of Piet Oudolf over the years.

Those are just a few of the many hundreds of people I’ve met and become friends with in three decades. As I walked through the Meadow again, looking up at the compass plants giving the nearby skyscrapers a run for their money,……

….. I thought about spring 1999, when I’d visited Hummelo and photographed Piet Oudolf on the eve of the new millennium. He would begin the Lurie design process just a year or so later. And of this garden, about which he said in a Tom Rossiter video recently, “The Lurie Garden created a moment in my life where I stepped over a threshold and came into another idea of design. For sure it has affected my work. And it has done a lot of good in my personal experience and it’s done a lot of good in my designs, in particular to touch people’s emotions.”

If there are big shoulders in cities, there are big shouldered people in the world of gardening and design as well. We stand on their shoulders and learn from them, and they sometimes learn from us. It is a rarified world rendered infinitely interesting by the changing of the seasons and by the way it touches our emotions. And we are all so very fortunate to live (and work) here.

Happy 15th anniversary, Lurie Gardens and Millennium Park.

*********

Please leave a comment. I’d love to know what you think of the Lurie, too!

I loved this post, Janet — and hope to visit the Lurie Garden again soon. You’ve done a wonderful evocation of why the Lurie Garden is special, and why the gardeners/designers/plantspeople who have made it and nurtured it year by year, make it a special place.

Thank you Lisa. It is such a rich story, even beyond the plants.

Lovely! What a community!

Thanks Mari Lise!

Wonderful post Janet. I always visit the Lurie when in Chicago, and I really appreciate the extra context you shared here. This garden is in my top 10- who can’t love how the sounds of Michigan Ave just fade away when you enter through the shoulders. You still see the fantastic architecture looming above and yet you are in a plant created cocoon.

I love the phrase “plant created cocoon”…. Thanks for the kind words!

Janet,

What a fascinating read…the history, the plants and the friendships. Chicago’s Lurie garden was the highlight of our GardenComm tour, it had been on my bucket list for some time. You continue to inspire me with you photography and writing!

Theresa

Theresa…. thank you for those lovely words. I was so happy to be seeing the Lurie finally, but also to be sharing the visit with you and so many other friends in the industry. Keep on writing those columns. You’re lucky to have your platform and you use it well.

Janet,

What a fascinating read…the history, the plants and the friendships. Chicago’s Lurie garden was the highlight of our GardenComm tour, it had been on my bucket list for some time. You continue to inspire me with you photography and writing!

Theresa

Thank you Theresa. Sorry not to have responded right away…. some comments get hidden!

Janet, Your story about the Lurie Garden is like a love letter to nature. Thank you for sharing your beautiful thoughts and pictures. The garden is one of my favorite places in the city. An calming oasis amidst the city hub bub. I learned more about the garden from this story than in any other article. Thank you for this gift. The Lurie has sparked so much good in making native plants popular. So many good things have come from building and maintaining this beautiful spot. So many people have been inspired to plant their own little Lurie in their yards. I hope you enjoyed your visit to Chicago.

Cindy Watts

Cindy, thank you so much! I’m so happy my blog helped you learn a little more about the history of this beautiful oasis in the middle of your wonderful city. I hope to return in different seasons to see the salvia river and the autumn color too!

We are lucky to have you, Janet … an artistic and discerning eye, a deep love of back stories, a pollinator protector, and a plant geek extraordinaire. Thank you for sharing your journey.

Thank you, dear Naomi! What lovely words…. I do try. It was three years ago that you came to lunch up here! Time is moving so quickly. That memory came up the other day in my FB memories…. And it was such fun to hang with you again at the High Line and our Oyster Bar dinner. Intriguing photos from you….. waiting for more!