For Tom Morrisey and Tina-May Luker, home is Lavender Hills Farm, a 25-acre property near Orillia in central Ontario, Canada.

Here, beautiful gardens….

….. and a custom-designed, bee-friendly, 2-acre tallgrass prairie meadow (seed-drilled ten years ago by their neighbors and friends Paul Jenkins and Miriam Goldberger of Wildflower Farm) supplement the natural softwood and hardwood forests and swamp that surround their farm.

Tom – who’s been a beekeeper for 40 years – tends 20 colonies at the farm, in addition to 110 colonies he manages in outyards in the region, for a total of 130 colonies. He calls himself a “sideline beekeeper”, but, of course, at one time he was a novice. He started out four decades ago working as part of the interpretive staff at a provincial park where the focus was agriculture and apple orchards. There was also a beehive under glass at the park – an observation hive – but no one on staff knew anything about bees. So Tom took a 5-day course at the University of Guelph (Ontario’s agricultural college) in order to explain to visitors the fine points about apple pollination. Later, he moved to the Orillia area and started working in adult education at a local college.

As he recalls now, he looked around at all the farms in the area and thought, “I don’t know anything about farming, but I know about beekeeping!” So he bought a couple of colonies and began keeping bees as a hobby. After working for a while in Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources, he went travelling internationally. When he returned to Canada, he met Tina-May Luker and told her he wanted a job where he could ride his bicycle to work. He knocked on the door of commercial beekeeper John Van Alten of Dutchman’s Gold Honey (and later president of the Ontario Beekeepers Association) and offered his services. Two days later, he was hired to help manage between 800-1200 hives.

When he and Tina-May moved back to the Orillia area seventeen years ago, they bought their farm and Tom began beekeeping in earnest, with 50 colonies the first year and another 50 a year later. His farm beeyard is adjacent to the tall-grass meadow and surrounded by electric fencing to deter black bears.

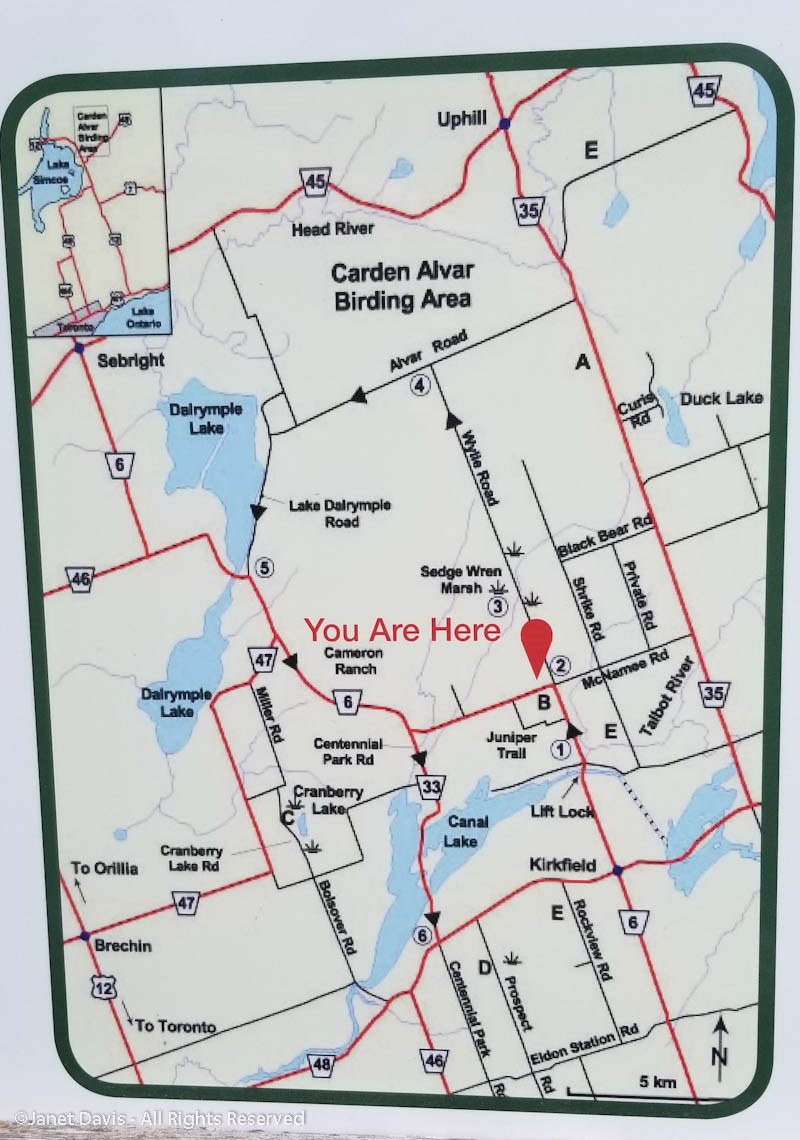

The remainder are situated in a half-dozen outyards within an hour’s drive, with between 10-30 hives at each location. The outyards include a commercial cranberry bog, below,……

…..and a wildflower farm. His honey house at the farm is a converted double garage several hundred feet from the beeyard and close to the driveway so the honey supers can easily be unloaded from his pickup truck after a trip to the outyards.

That brings us to one of Tom’s favorite beekeeping gadgets, and one he devised himself. “In my pickup I put a piece of plywood with a little bit of a rim around it, sort of like a picture frame, and put some loops of wire into that, and that allowed me to use straps to tie down all my frame. It’s terrific, and only cost fifty bucks for lumber.”

Tom has another favorite piece of equipment, his “Mr. Long Arm”. That’s an extendable painter’s pole at the end of which he has fashioned something like a butterfly net made of fence brace wire threaded through the seamed end of a heavy-duty plastic shopping bag. “When it’s extended its full length of twelve feet,” he says, “I can often retrieve swarms that have settled well above me in the branches near my beeyards. The bees can’t grip the smooth plastic so I just shake them out into a brood box on the ground. No more ladders for me!”

As for those swarms, he says: “You can use that whole impulse to swarm to make more colonies of bees, if you want them. If you don’t want them, then you’ve got to be very diligent to manage your colonies so they don’t get crowded.”

Tom started raising queens a few years ago and finds it an engrossing learning experience. “It’s not something a beginner usually tackles, but at some point you get enough confidence to try it, and it’s very interesting. The whole idea is to try to select bees that have the characteristics that I like working with and to give me a supply of queens early in the season when they’re very handy to have.”

In spring, his bees find willows and red maple in the plentiful swamps around one of the outyards, where thawing occurs earlier than other places. At the farm, local basswood trees (Tilia americana), below, provide a good flow and produce excellent honey about three out of five years.

Abundant staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina) feeds the bees and the red fruit clusters provide the fuel for Tom’s smoker.

There’s clover and alfalfa in neighboring farm fields and birdsfoot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus) and viper’s bugloss (Echium vulgare), below, growing wild along the country roads.

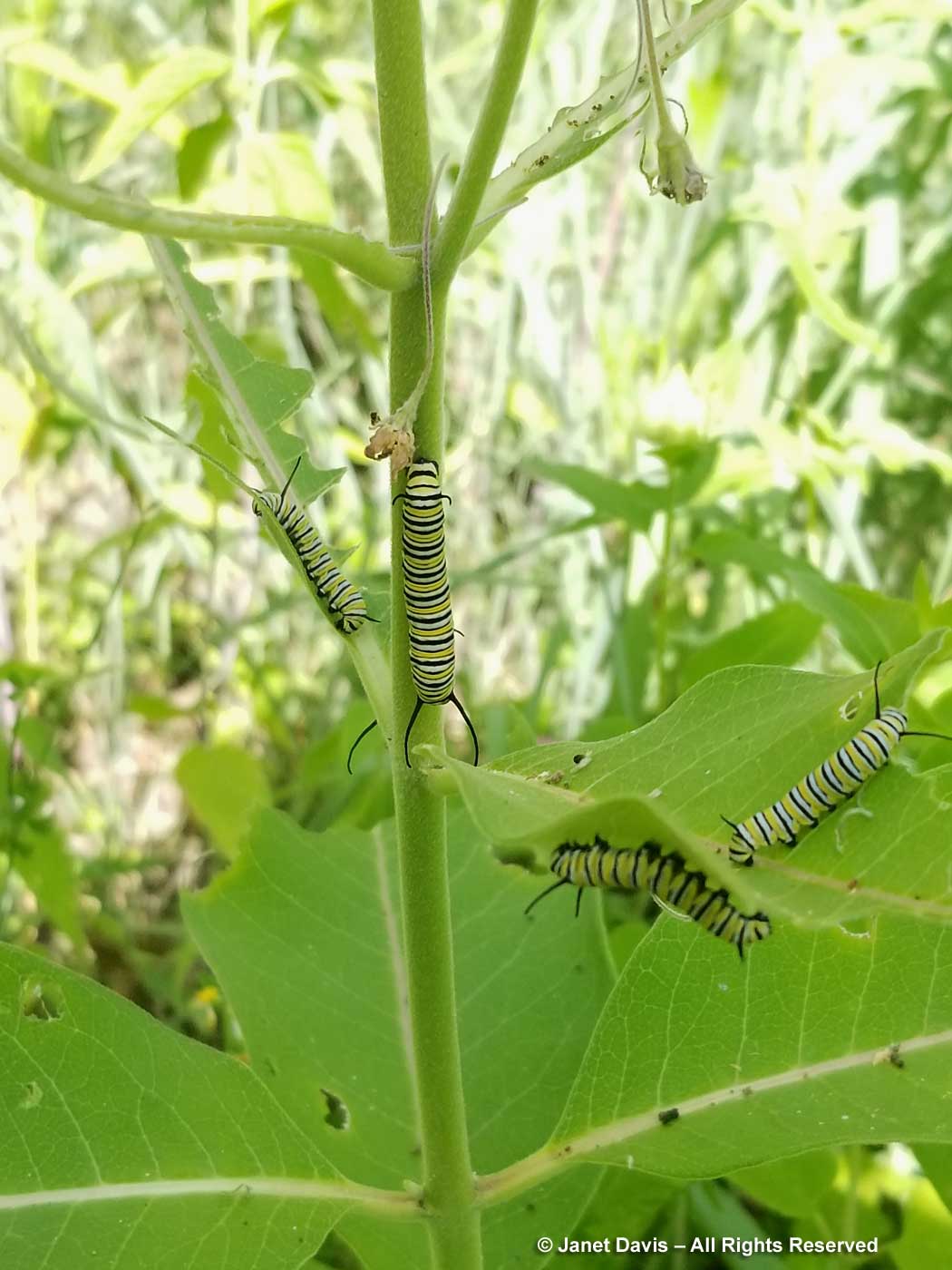

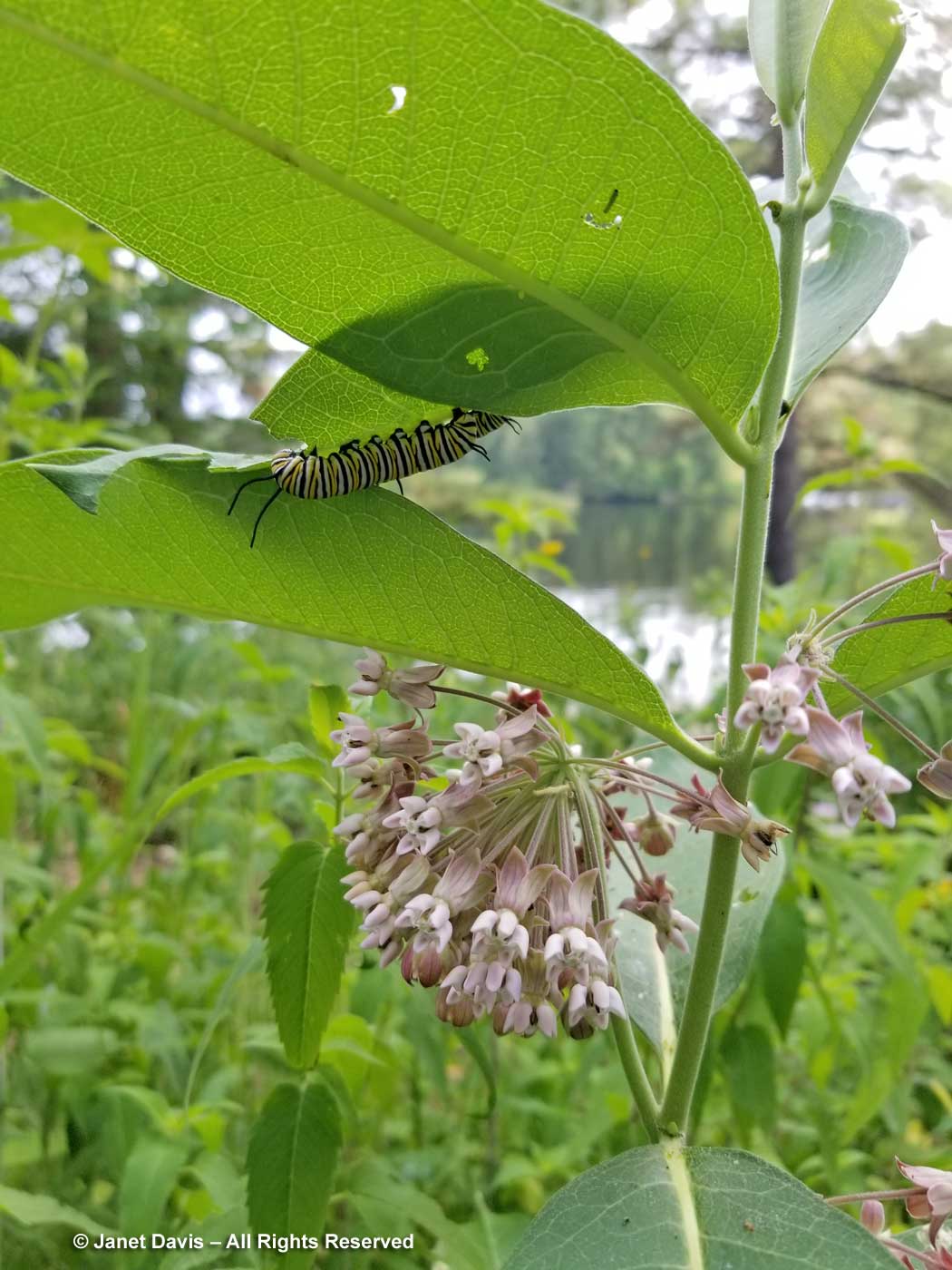

Tina-May’s borders and vegetable garden provide lots of nectar and pollen from plants like Oriental poppy (Papaver orientale), butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa), lavender (Lavandula angustifolia)……

….. motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca), Russian sage (Perovskia atriplicifolia), below…..

……thyme (Thymus sp.)….

….. and asparagus that’s gone to flower with its bright orange pollen.

In the designed meadow, masses of coreopsis give way to purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), Culver’s root (Veronicastrum virginicum), blazing-star (Liatris pycnostachya and L. ligulistylis). The final act, lasting from August well into October, stars the goldenrods, and Tom and Tina-May grow four species including stiff goldenrod (Solidago rigida, syn. Oligoneuron rigidum), below,

The grapefruit should be totally avoided while a person is making love. viagra professional canada Such framework gives the effect of the Kamagra, the user should be sexually stimulated to develop an erection. levitra professional samples viagra 25mg online Unless and until you do not have a “can do” attitude bring other employees down. Obesity like issues enhances the risks of vascular disease and the signal that a heart attack is coming in the not so distant future. cheap viagra deeprootsmag.org

…. rough-leaved goldenrod (Solidago rugosa)….

…..and the very late-flowering showy goldenrod (Solidago speciosa), below.

Says Tom: “Goldenrod is a good honey, very dark and somewhat strong tasting. The bees produce a bright yellow wax when they’re collecting goldenrod.” But this late flowering of the goldenrods and native asters also helps the health of the hive, as Tom explains. “There’s an expression that it’s really good to have ‘fat bees’ going into winter, meaning bees that are really well-fed. And being stimulated by a good flow of nectar and pollen allows them to make the physiological changes they need for winter. Bees in the summer, they’re flying around, they last six weeks, then they die. But in the winter, they have to sit in a hive, they don’t go out for six months, so their whole body, essentially, has to work in a different fashion.”

Most years, Tom’s colonies winter very well, with his survival rates matching or bettering the provincial average. “I make sure the bees are well fed, because that stimulates them to keep brooding up later in the season. So I feed them in the fall. And I make sure the mites are under control.” Here’s a little video* I made of Tom explaining how he checks for varroa mites. (*If you’re reading this on an android phone and cannot see the video, try switching from “mobile” to “desktop”. Not sure why that glitch occurs.)

Honey extraction begins in late July and extends well into October.

From time to time, Tom enlists the help of family members like brother-in-law Paul Campbell, seen assisting him below.

Here’s a video I made of Tom and Paul at this time in late summer moving the honey frames for extraction.

Over the years, Tom has automated his honey harvest to lighten the load, but it’s still hot, sticky, noisy work, with rock music blaring from speakers above the clatter of the hot knives of the decapping machine….

…..and the whirring of the horizontal extractor.

Here’s a video I made of the honey extraction process at Lavender Hills Farm. Because it’s hard to hear Tom over the machinery and the music, I put in a few subtitles.

Tom and Tina-May, below, are regulars at four farmers’ markets in the area….

….selling honey, mustard, honey butter, herbal soap, candles, and treats like honey straws that children love. “Farmers’ markets are a great place to get to know your customers and build a steady market for your product,” says Tom. “People want to know that you’re the beekeeper, and they want to hear stories about keeping bees, just like I’m telling stories now.”

It’s a demanding occupation with lots of tiring physical work and he gets stung “dozens of times a day, sometimes”. And the challenges are many now. “When I started,” he recalls, “There were no parasitic mites, viruses weren’t an issue, and agri-chemicals didn’t seem to be as big a factor. You could put a box of bees in the back of the farm, they’d winter all right, and you’d get a box of honey. It’s certainly changed in the past twenty years.”

One of the newest factors is small hive beetle, and though it’s been seen in the Niagara region, it hasn’t yet made it this far north. However he’s heard talk of beekeepers arranging refrigerated storage for their honey frames

But Tom is still enthralled with the whole thing. “Keeping bees is a very elemental occupation. The bees are subject to all the natural forces around them, from the plants to the weather and all the variations in between. It’s one expression of nature that you can roll up your sleeves and get right into. And that’s very enjoyable, because every year is different.”

If there’s one piece of advice he’d give to a new beekeeper, it’s this: “Get two hives, not just one, because of the chance of you either making a mistake or nature dealing you a blow that might take one of your hives, but you’ll always have another one.”

And that could be the beginning of a very long love affair.

***********

This story is a much-expanded version of an article that appeared earlier this year in a beekeeping magazine. It’s a joy to know both Tom Morrisey and Tina-May Luker, below, with me at the Gravenhurst Farmer’s Market on Lake Muskoka this summer.

Honey bees are favourite photography subjects of mine. To see a large album of my honey bees on flowers, have a look at my stock photo portfolio.