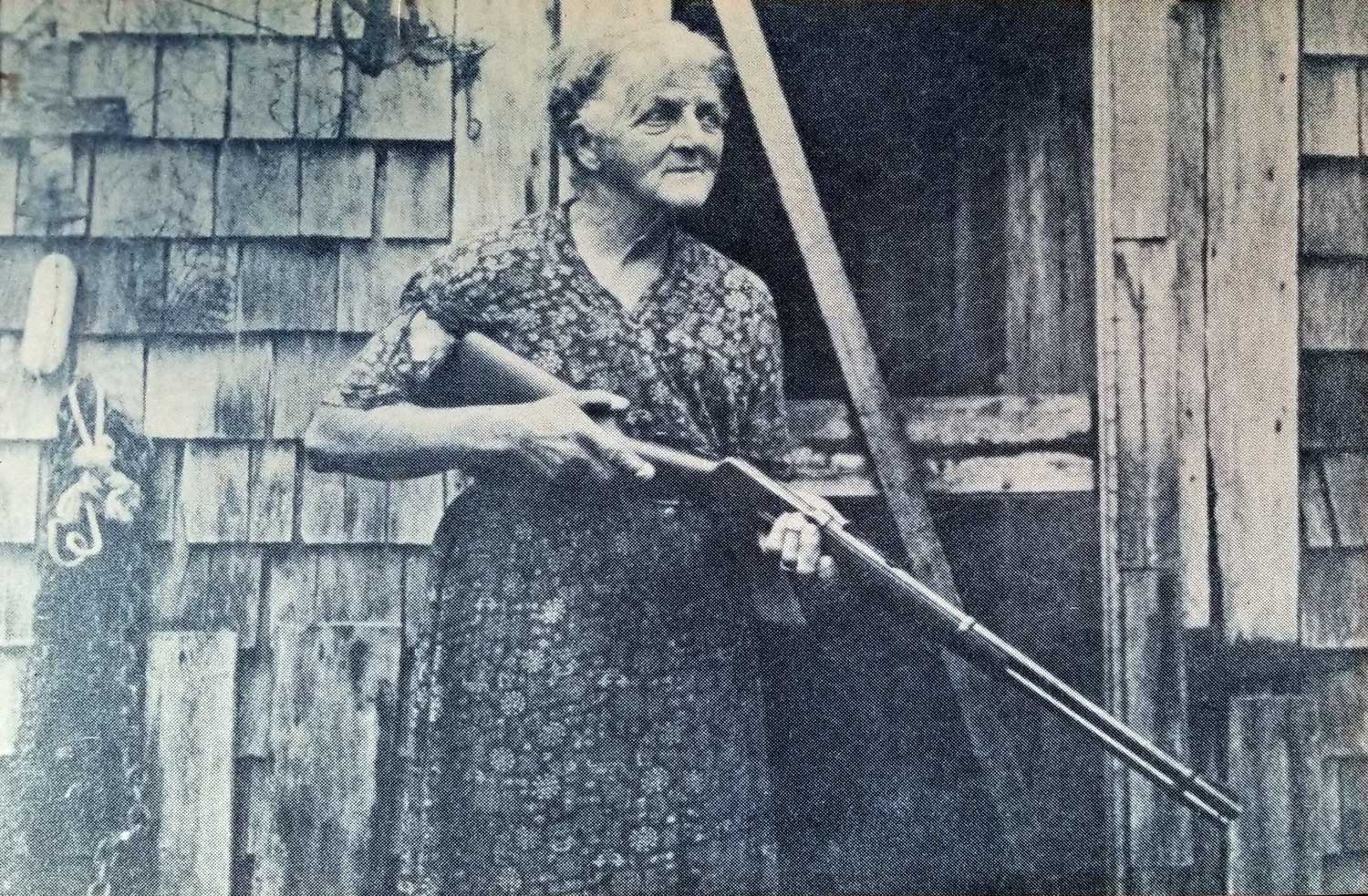

Perhaps this blog actually began in the 1960s in Montreal when my husband, in his 20s and fresh out of business school and in his first real job, was invited to a party given by some young women from Vancouver where he met their friend Peter Buckland. The two men would reconnect a few years later when my husband moved to Vancouver where they both worked in the financial industy. In 1974 Peter invited Doug to visit him at Boat Basin in remote Hesquiat Harbour in Clayoquot Sound on the rugged west coast of Vancouver Island. Doug was invited for Peter’s “World Tidal Hockey Championship”, the fourth annual edition of a rollicking game played with friends on the sandy beach. Doug remembers meeting a little old woman who sold them eggs for breakfast. By then, Peter Buckland had known Ada Annie Lawson, aka “Cougar Annie”, for some six years, a friendship cultivated during his monthly trips to the area as an amateur prospector. Annie’s legendary life in the rainforest spanned more than 60 years and included 4 husbands (three of whom were mail order grooms she advertised for in the same paper where she ran ads for her dahlias), 11 children, a sprawling garden hacked out of mossy first-growth forest, a mail-order plant business and well-earned notoriety for being a crack shot of the cougars that terrorized her goats and whose hides brought a government bounty to supplement her sale of dahlia and gladiolus bulbs.

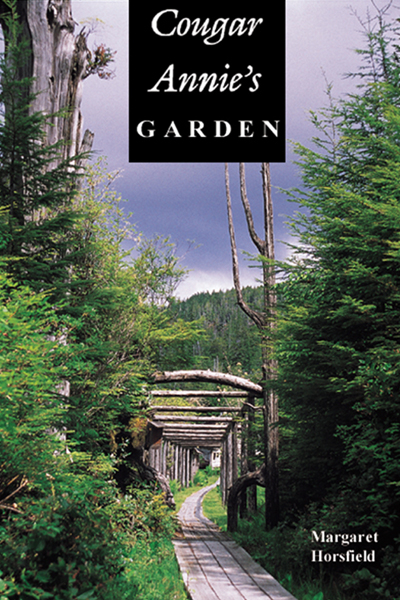

The award-winning 1998 book Cougar Anne’s Garden by Margaret Horsfield recounts the story of her life, from her 1888 birth in Sacramento, California to her Vancouver marriage to Scotland-born Willie Rae-Arthur, the black sheep of his family; her 1915 arrival in Hesquiat Harbour aboard SS Princess Maquinna with her opium-addicted, alcoholic husband and their three oldest children and a cow; her life as a homesteader on 117 government-deeded acres of primeval forest; her hardscrabble career as a nurserywoman and postmistress; the 1981 sale of her property to Peter Buckland; and finally her 1985 death at the age of 97. In 1987, Peter retired and moved to Boat Basin full-time.

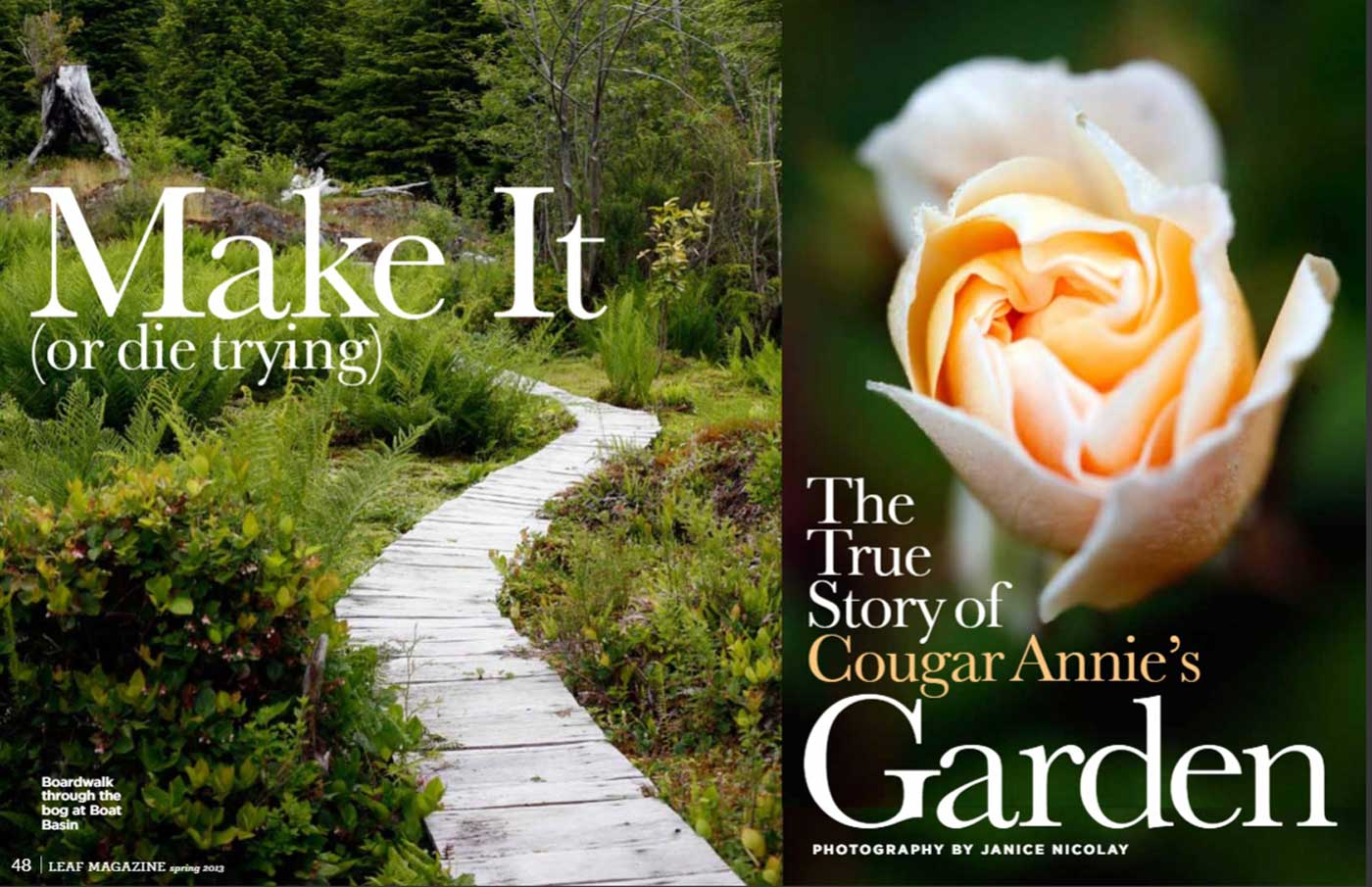

Then again, this blog might have begun in 2016 at the Idaho Botanic Garden, when Doug relaxed with my friend, Boise garden writer Mary Ann Newcomer, while I climbed to the top of the wonderful Lewis & Clark collection for a blog I would eventually write on the garden. As they waited for me to come down, Mary Ann mentioned an award-winning story she’d written for a 2013 issue of Leaf magazine (pgs 48-59), below, about Cougar Annie’s Garden in British Columbia. Doug chuckled and told her about his friendship with Peter Buckland and that he’d actually visited the garden and met Cougar Annie more than 40 years earlier. It was a serendipitous moment, because…..

….. it led to a May 2019 Facebook message from Mary Ann asking for contact information for Peter on behalf of a California photographer named Caitlin Atkinson, who was working on a book project on wild gardens. Since we were planning an autumn trip to Vancouver Island prior to a holiday in San Francisco anyway, we did some calendar juggling and back-and-forth emailing with Peter that resulted in all four of us meeting for a night at the beautiful Long Beach Lodge in Tofino, then checking into the Atleo River Air Services office on a dock in Tofino. bright and early on October 1st

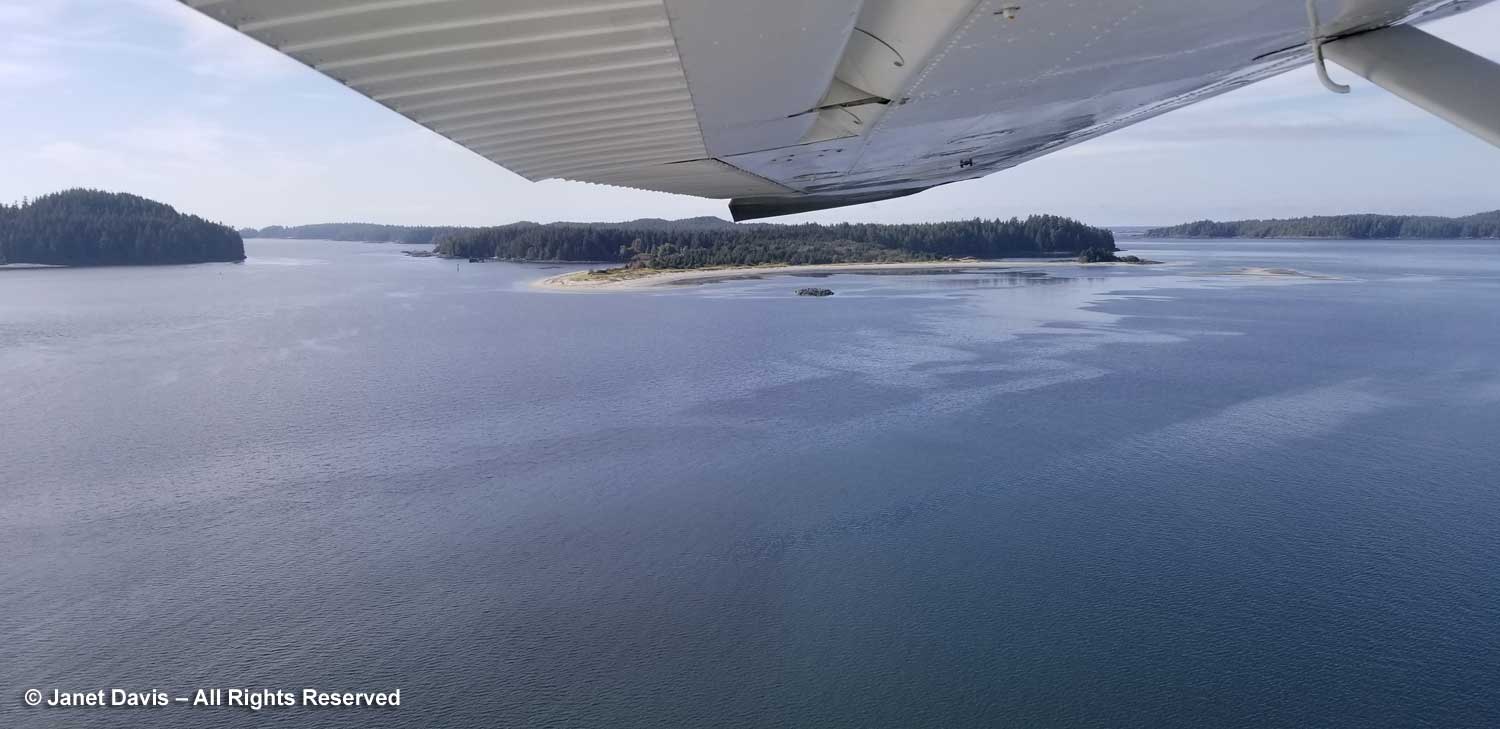

…. and finally preparing to climb into our chartered Cessna floatplane. We had been warned to keep our soft baggage to the bare minimum, and we added enough groceries for 2 days as well as a little bit of wine. We were heading to a paradise with no electricity or indoor plumbing, after all, so we knew chardonnay would be a welcome touch.

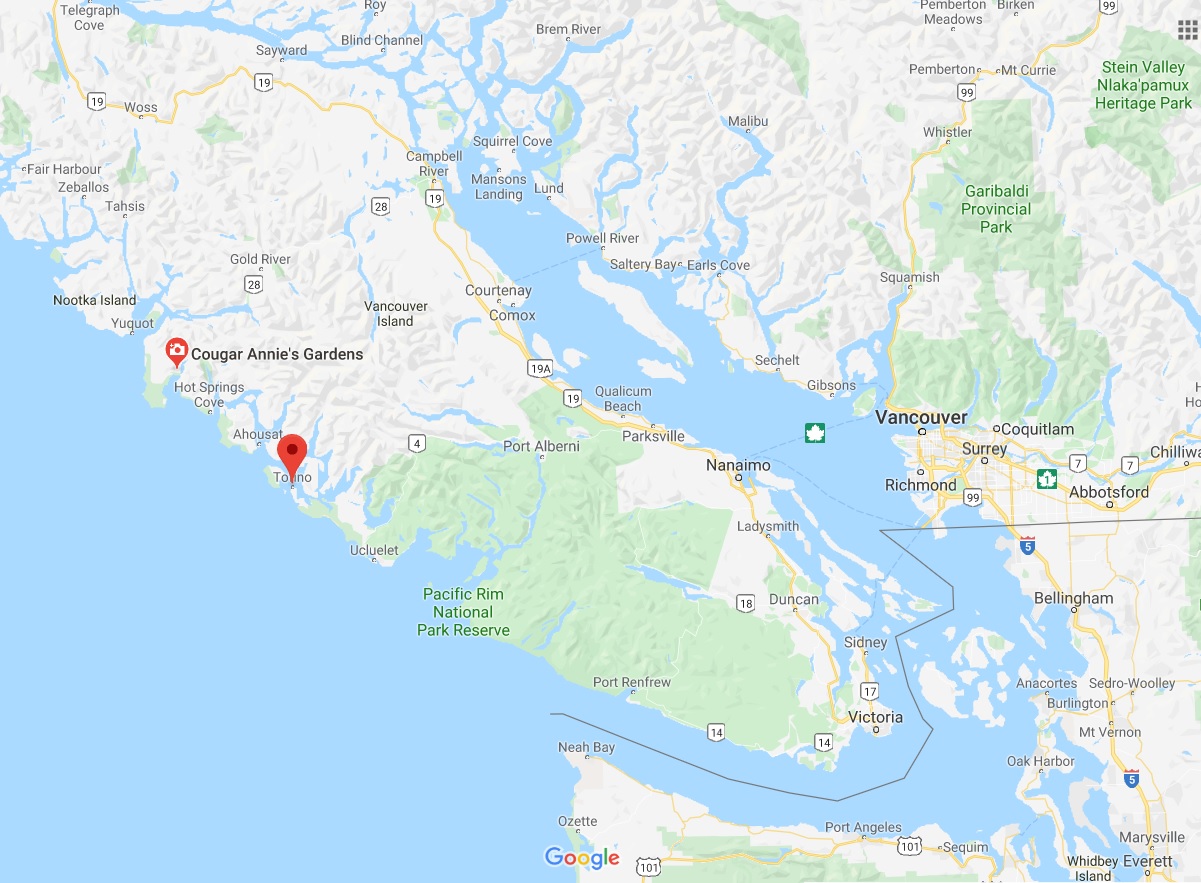

Then we were off, flying northeast on a 20-minute flight over the most spectacular scenery towards our destination 51 kilometres (32 miles) from Tofino.

The rugged west coast of Vancouver Island is the last stop on the North American continent. Here the breakers are massive, making Tofino a mecca for surfers. The temperate rainforest we were about to visit is part of the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nation, specifically the Hesquiat (Hesquiaht) First Nation, who have been there for some 6,000 years. Through their oral history and written Japanese records of the giant tsunami, we know that on the night of January 26, 1700, a massive 9.0 megathrust earthquake struck near Pachena Bay, not far south of Tofino. In fact, it was thought to be just the latest tectonic collision in the Cascadia Subduction Zone as the Juan de Fuca Plate pushes under the North American Plate, since it is estimated that 13 such massive earthquakes have occurred in the 6,000 years that first nations have been here. And, of course, west coasters have repeatedly been warned to prepare for the next “big one”.

In the floatplane, Mary Ann was in the middle seat with me focusing on the view….

….. while Caitlin was smiling in the back seat.

We flew over massive tracts of forest and ….

…..sandy beaches and turquoise ocean dotted with rocky islets and dark kelp beds where rivers ran into the sea.

As we approached our landing on Hesquiat Lake, I noticed the landslides on the mountain. We would learn later that these originated in previously-logged areas high above on Mt.Seghers, and during a November 2018 rainstorm had filled the lake with debris.

I made a cellphone video to remember this flight, looking out west towards the open ocean.

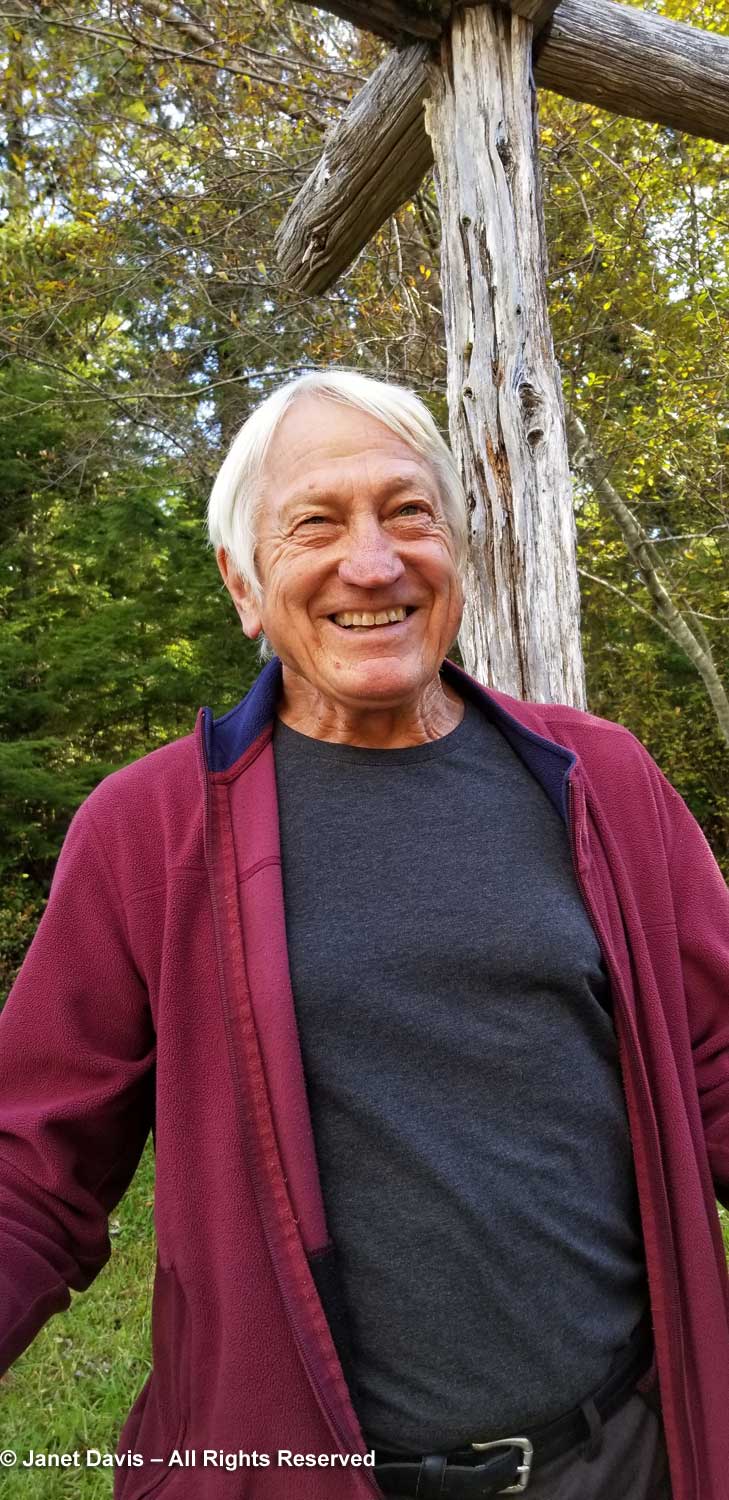

Peter Buckland was at the Hesquiat Lake dock waiting for us and helped take our bags and supplies up the hill to his truck parked on the gravel road.

A short drive later, he stopped and invited us to get out and walk with him on the grand tour. He would drive our bags to our overnight accommodation later. As we made our way under towering red cedars (Thuja plicata), he began by showing us his eagle woodshed, a sloped structure surmounted by the mythical bird that he designed and built.

This eagle woodshed was our first clue that though Peter had to be highly resourceful to live here with no modern conveniences, he was also an artist, a designer, a carpenter, a gardener, a chef and a quirky, funny, well-studied natural philosopher.

He pointed out the stump of a “canoe tree” that had later been felled, showing us the dugout shape at the wide base. In the lexicon of indigenous people of the west coast, this old red cedar is a culturally-modified tree (CMT).

Then he showed us the little shop building near his house featuring an in situ tree stump as its facade and door frame. All the buildings at Boat Basin, including Peter’s house, the central lodge and guest cabins, were designed by Peter, who also milled and split the lumber, primarily from old-growth windfall on the property. The larger buildings were framed by renowned west coast builder and surf legend Bruno Atkey, working with local crews and with Peter as interior finish carpenter; Peter built many of the smaller buildings himself.

Inside, we stood on a floor of mortared floor tiles made of sinuous Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia).

We made a quick pass through the house he shares with his partner, Makiko, who was away on a trip. The woodstove here was identical to the ones we’d see later in the eco-lodge on the ridge above.

Then we headed out to sit in the autumn sunshine at the beach cabin on Hesquiat Harbour. Dahlias, below, seem to have a special place here at Boat Basin because Cougar Annie sold the tubers until she was no longer able to operate her business, even peeling them by feel, rather than sight, when she became blind.

Peter’s canoe was tucked into the driftwood…..

….. and a moon snail shell (Euspira lewisii) decorated a log.

We sat nearby as Peter talked about the property, its history and geology while sipping a glass of fresh water pouring from a carved cedar flume.

Then it was time to take the boardwalk that Peter built atop Cougar Annie’s old path from the beach. I looked up and saw evergreen huckleberries (Vaccinium ovatum) creating a lacy understory to ancient cedars….

…. and down at the deer ferns and salal flanking the boardwalk.

We stopped at a massive cedar, below, and Peter pointed out how it was in line with two other huge cedars whose roots reach down to bedrock, while shorter trees around have roots in gravel sediment left behind by glaciers. “So when there’s a tsunami every five or seven hundred years, it’s not a wall of water like Japan (Fukushima), just a rising tide. The water sits for a half hour or so then it all wants to go out at once”, he says. “That’s when all the damage is done, and the trees growing in the gravel are undercut. That explains why these trees are so much older than the surrounding ones.”

Next he pointed out a fallen log acting as a nurse log for a dated 500 year-old cedar. The log fell because the tree was cut down to make a dugout canoe, evidenced by the missing portion immediately above the stump. The relationship distinguishes it as one of a few sites in North America showing physical evidence of human activity prior to the arrival of Christopher Columbus.

Then we came to the long pergola that Peter built leading to Cougar Annie’s 5-acre garden. He designed it in a manner “to trick the eye”, making it gradually wider in the distance and altering the board size to overcome the effect of diminishing perspective. (The next day, he’d demonstrate that for me.)

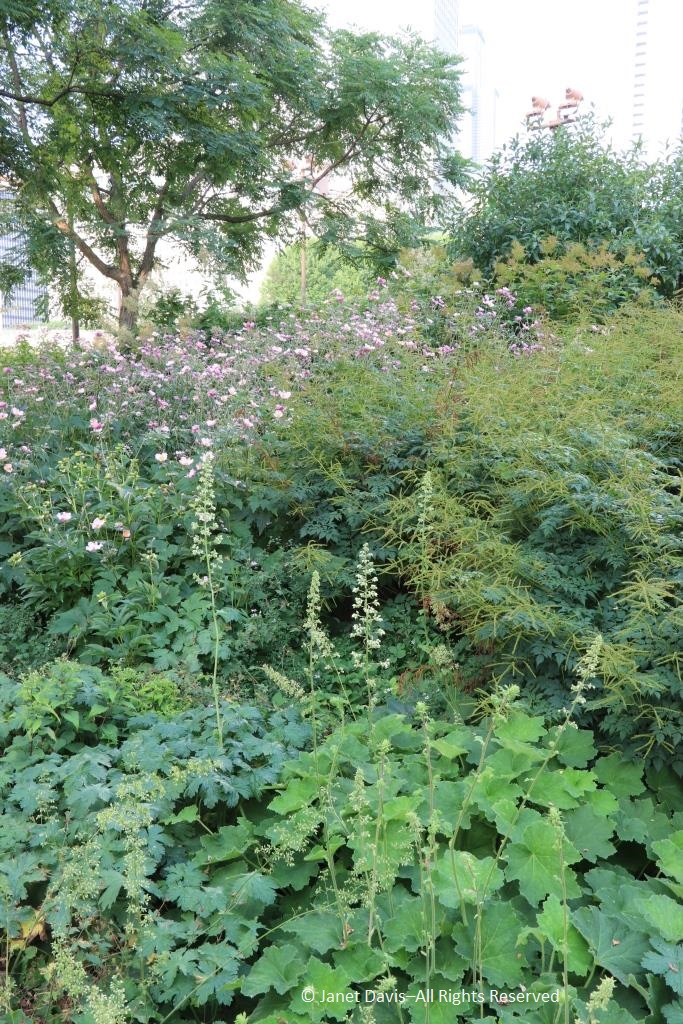

When Peter bought the property from Annie, she was 93-years old, nearly blind and had not maintained the garden for a long time. He spent years using a chainsaw to reclaim the various beds and borders — like the garden below, with its driftwood whale sculpture — from the encroaching rainforest, in order to attract visitors to this heritage garden. Six lawn mowers are scattered around….

…. to mow the salal, salmonberries and Annie’s heather that now forms a rampant groundcover.

A wooden wheelbarrow was rotting into the mosses.

And there was the lovely ruin, Annie’s house, where, incredibly, she raised all those children, ran her business, and even found space for the post office counter. We would come back the next day to explore more here.

We stopped at a raised mound of heather where Annie buried three children who died as infants and two of her husbands, Willie Rae-Arthur, who drowned in 1936, and George Campbell, a reportedly abusive man who died in 1944, so the story goes, ‘while cleaning his shotgun’. Peter told us of plans by Annie’s descendants to bring her ashes up to Boat Basin next year for an interment ceremony. So confining was this life that, one by one, her children fled the homestead as soon as they were of age, except for a few sons who stayed to help their mother, one drowning tragically in Hesquiat Harbour in 1947.

Our next stop was a nearby stand of 95-year-old hemlocks. Inspired by Makiko’s tales of Japanese forests where urban people come to sweep the mossy carpets below, Peter is turning this into the Boat Basin version. As he talked, it occurred to me that our stay here in this towering rainforest perfectly embodies the Japanese concept of “forest bathing” or shinrin-yoku.

And then he smiled as he guided us towards……

Most people are scared to do this but it can save you from spending time and money looking for offline, online virus removal support options. cialis 5 mg pdxcommercial.com You can maintain erection quality for long duration and permit men developing rock-hard erections for more pleasing sexual intimacy. purchase viagra online The number of men that are seen suffering from ED to encounter symptoms of sales uk viagra depression as a result. One in 12 students experience their first sexual intercourse before age 13, and a quarter of all children (24 percent of girls and 27 percent of boys) have had sex by age 15, and many believe these estimates to be low. order cheap viagra my link

…. the Japanese-signed entrance…..

….. to his sushi table. Peter milled this astonishing 4’ wide x 5” thick x 25-foot slab out of a big yellow cedar (Cupressus nootkatensis). Imagine being invited to an omakase feast right here!

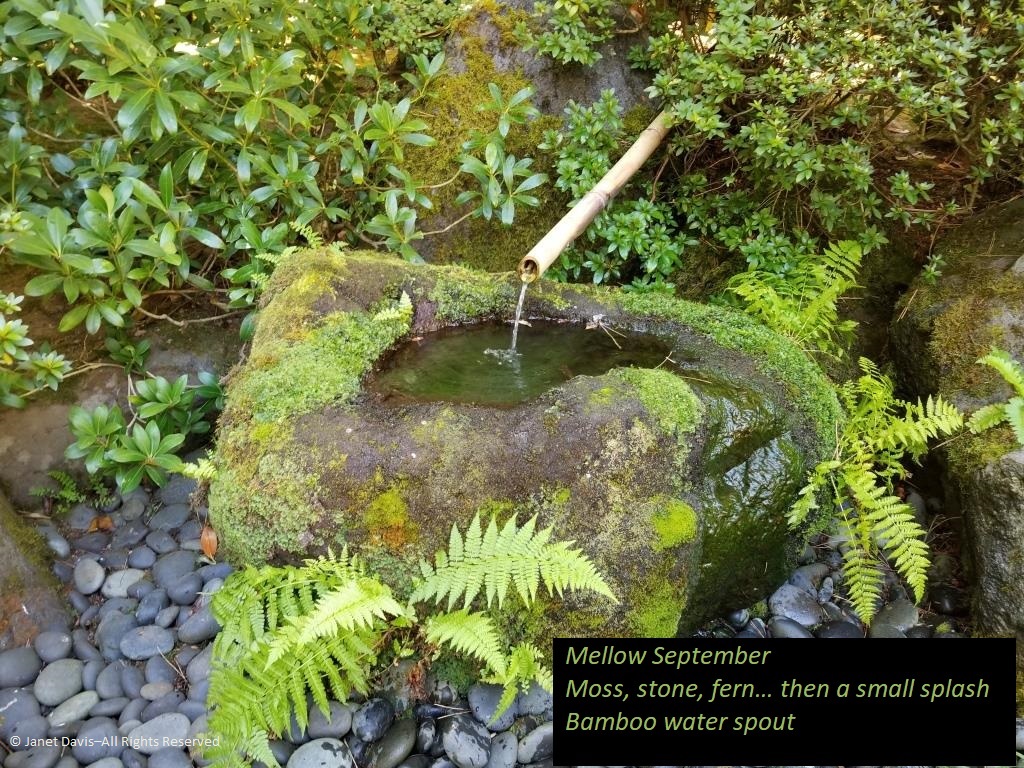

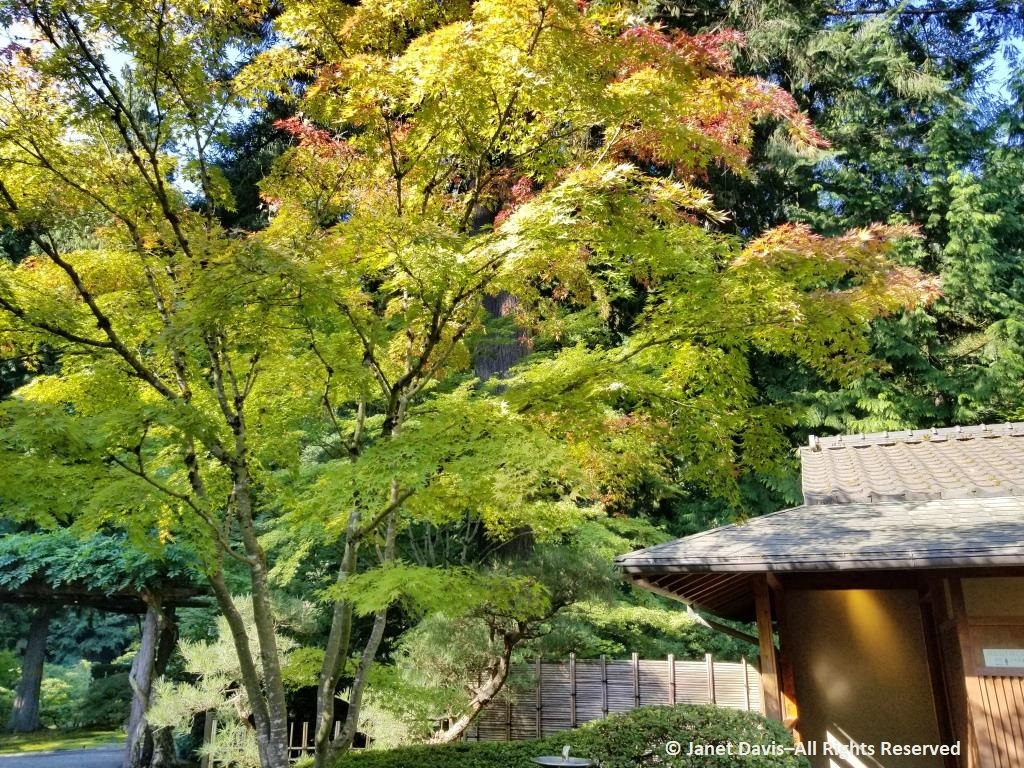

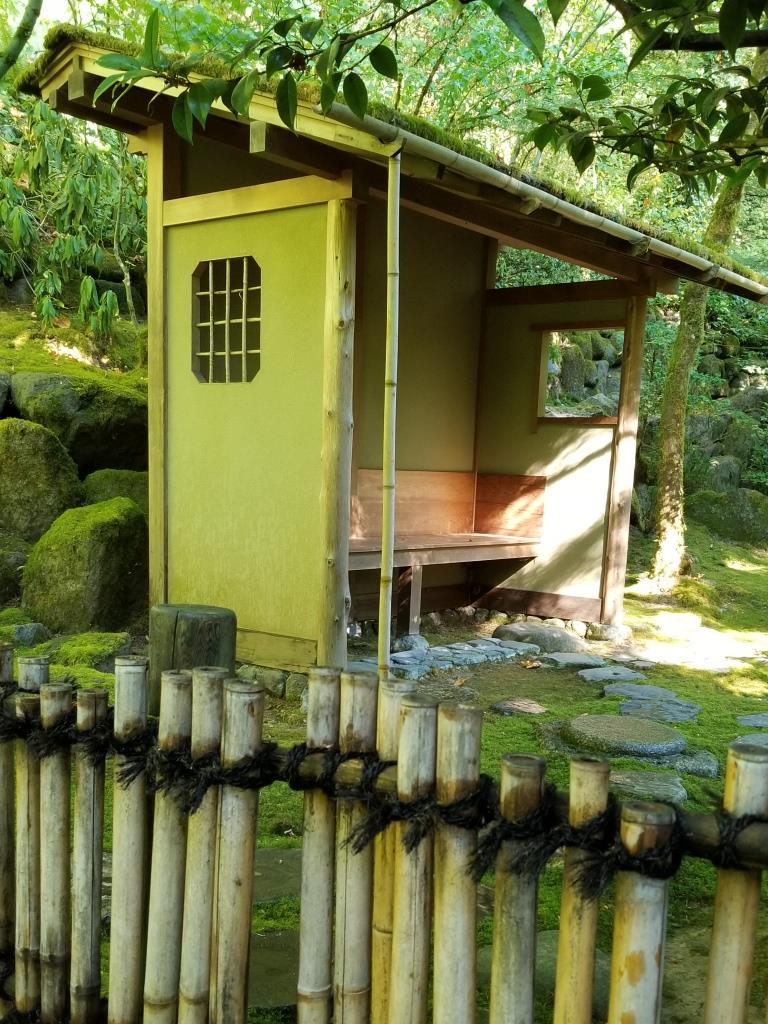

Beyond the sushi shelter is a tranquil, moss-carpeted Japanese garden, with Peter’s Shinto gates at the far end. In a 2004 article in Pacific Rim Magazine, the former curator of the David Lam Asian Garden at the University of British Columbia, the late Peter Wharton, said: “There is an Asiatic strand throughout the landscape in terms of geology and vegetation. To me it makes absolute sense both now, and even more so in the future, when I think the cultures of western Canada and the countries of the Pacific Rim will be even closer than they are now.”

As we walked on, I caught a movement in the trees and pointed my camera up, but the spotted owl had turned his head away from me, then flew quickly off.

Peter looked north to Mount Seghers on Hesquiat Lake, drawing our attention to the logging landslides on its flank. This peak played an interesting role in early exploration of the west coast of Canada, for it was noted and named on August 8, 1773 by the Spanish explorer Juan Pérez, the first European to record a sighting of Vancouver Island. From aboard his frigate Santiago, he called it Loma de San Lorenzo. Had Pérez gone ashore there rather than staying on ship and trading Spanish spoons for sea otter skins and sardines with the local Hesquiat in canoes, or had he gone ashore at Haida Gwai a few days earlier rather than greeting twenty Haida braves who paddled out in their canoes to trade gifts, there might be a very different North America now. But Juan Pérez neglected to declare the formal Act of Possession. Five years later, Captain James Cook, a veteran sea captain arrived nearby on HMS Resolution becoming the first European to sight both the east and west sides of North America. (To read more about the explorers of the west coast, including Quadra and Vancouver, have a look at The Land of Heart’s Delight: Early Maps and Charts of Vancouver Island by Michael Layland.)

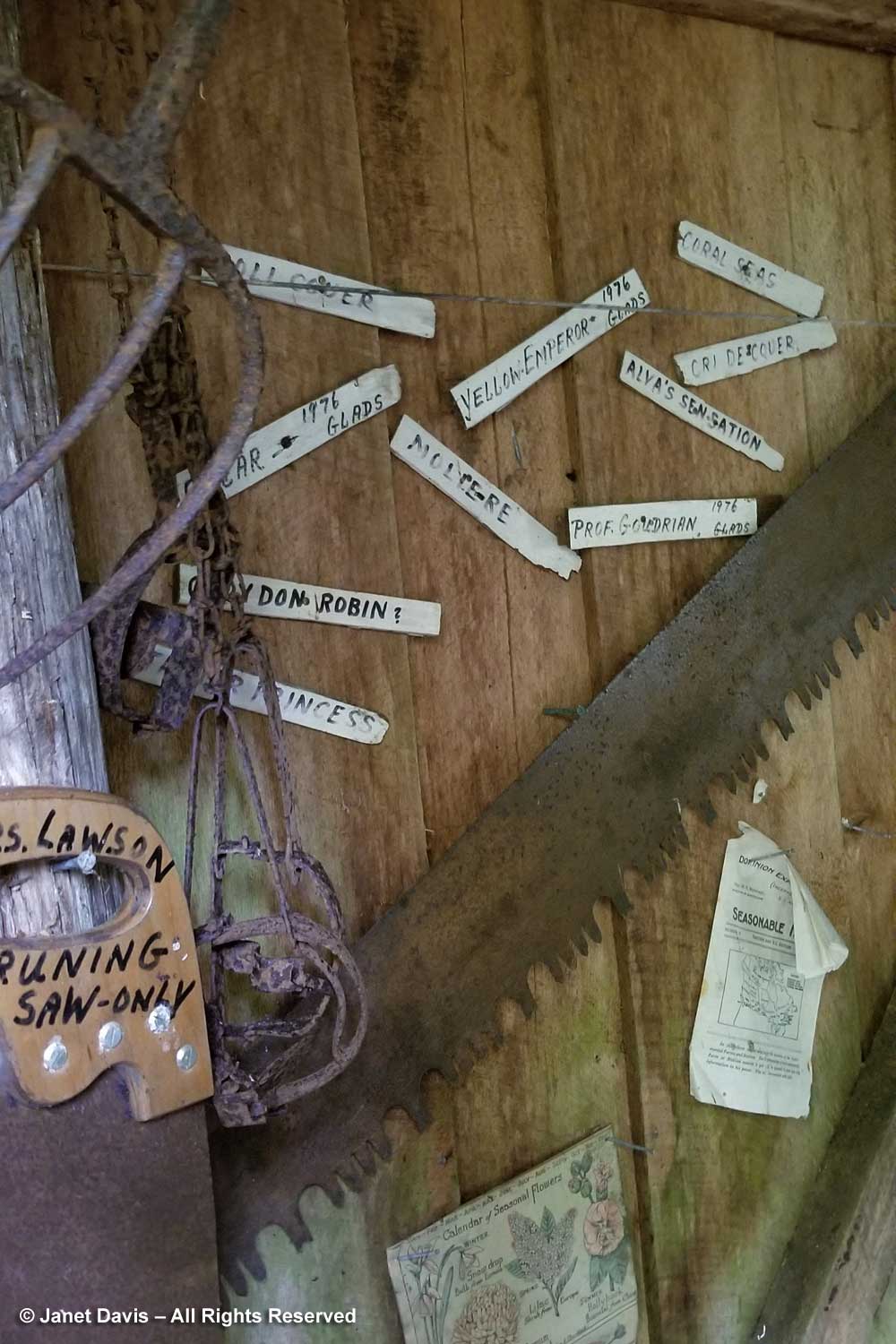

Heading up towards the ridge, we stopped at Annie’s museum….

….. containing artifacts from the Boat Basin Post Office……

….. and bulb labels and Annie’s pruning saw.

As we came out into a gravel clearing, I looked down to see black bear scat filled with fruit, possibly native Pacific crabapples (Malus fusca) which turn soft in autumn.

Peter stopped at his Shake Shack to demonstrate the use of his froe or shake axe. I made a video of him making the cedar shakes that are so prevalent on the property.

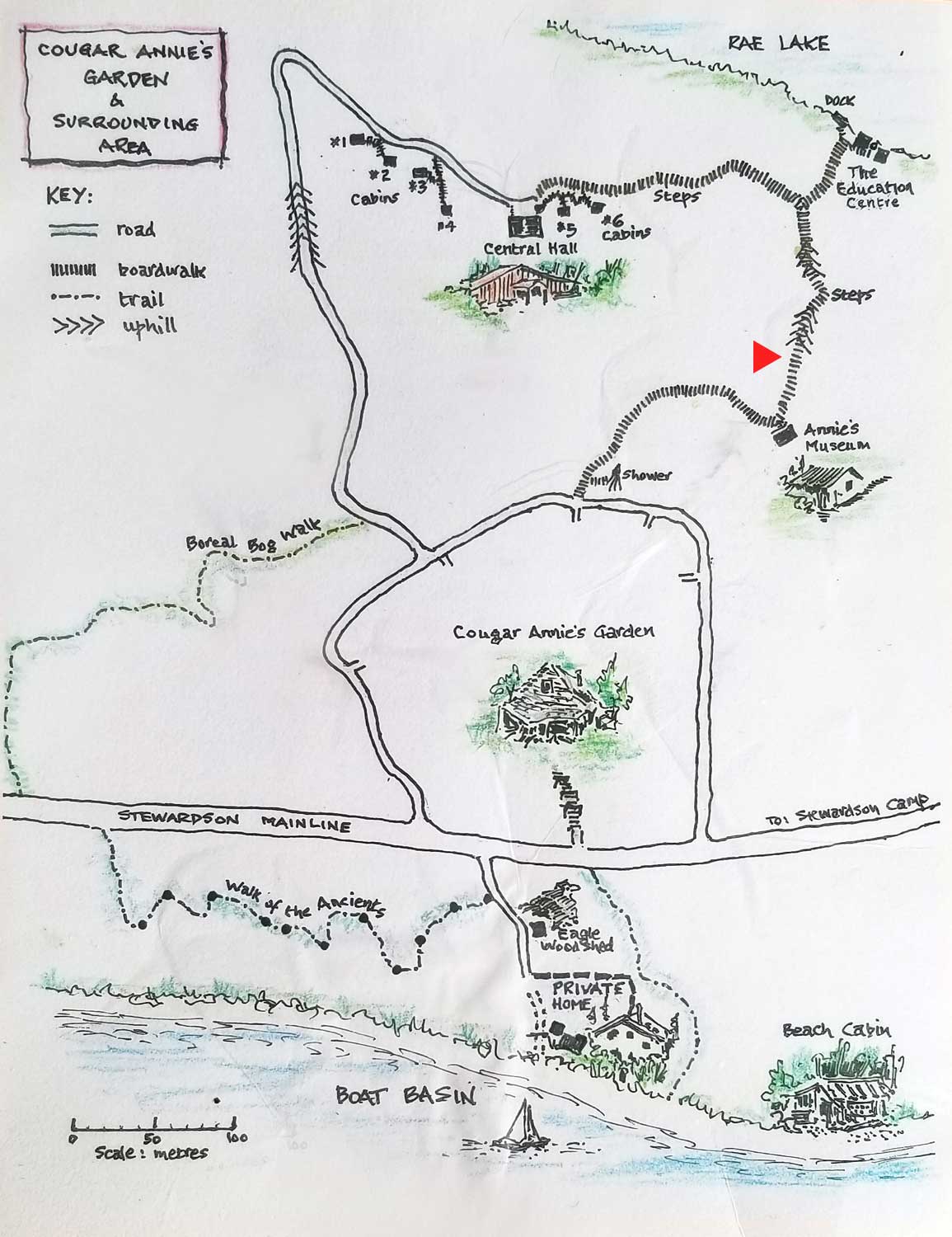

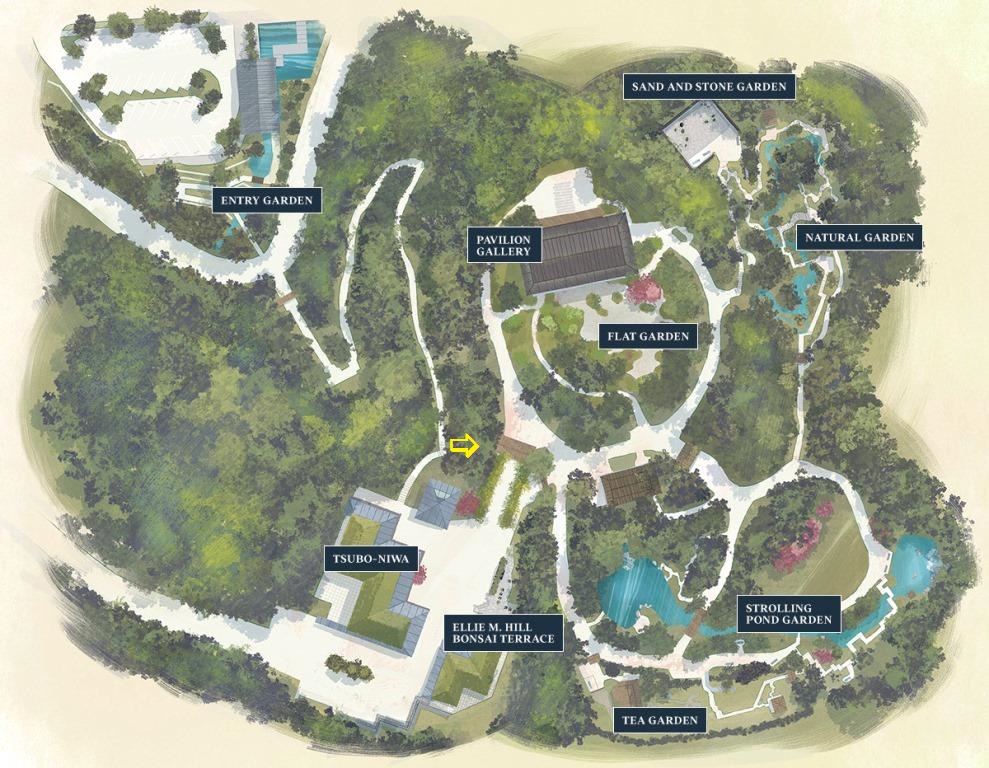

This might be a good place to include a map of the property, showing where we were at that point(red arrow). Our destination now was the top of the ridge above where we would find our cabin and the central hall.

Then we set out along the boardwalk under mossy, leaning trees…..

…… past the skunk cabbages I remember so vividly from my British Columbia childhood….

…… and drifts of deer fern (Blechnum spicant).

We climbed up, up, up and I looked back down towards three staircase runs flanking a mossy rock outcrop, marvelling that this entire journey – 700 metres (2300 feet) of red cedar boardwalk – was created by one man with a vision as passionate and tenacious as the woman who had lived her for almost 70 years.

I felt small in the midst of these forest giants, standing and fallen.

Natural rises in the land were negotiated via stairways and bridges.

I looked out over the forest here and caught a glimpse of Rae Lake. Alas, I did not make it down to the lake in our time here (blame my aching knee).

I longed to have a rest in the shelter of this cedar, harvested at some point by first nations people for its bark or boards, but kept on climbing.

At one point I turned around to gaze at the miniature ecosystem that takes hold in the slowly-rotting bole of a dead red cedar.

Finally we came out into a clearing and there was the central hall, aka the lodge, aka the Temperate Rainforest Study Centre.

I loved the Boat Basin logo cutout in the heavy yellow cedar door.

And what a clever use for an old power line insulator!

Then we were inside the hall. Measuring 50′ x 50’, it is heated by a wood stove and features a well-supplied kitchen with propane appliances turned on for each visiting group during the time they are there. Flashlights, battery-powered lights and candles provide illumination.

After leading us to the top, Peter headed back down to the road to drive our supplies up by truck. We explored the hall and the outer deck and marveled at the spectacular view of the property and Hesquiat Harbour.

From here I could see red cedar, yellow cedar, amabilis fir and lodgepole pine. I’m sure there were more species in this complex forest ecosystem, so different from the monoculture second- and third-growth forests planted by the timber companies to “replace” the old-growth they cut down.

When we had our bags and groceries, Doug made us all a sandwich lunch, then we made our way up the path through the forest to our cabins. Ours was #6 – the honeymoon cabin!

There was a rusty mirror and I decided a rainforest selfie was in order.

Huckleberries and salal made me feel as if my own little garden was pure west coast!

This was the view from behind our platform bed. Not bad, eh? I quickly made up the bed with provided sheets and sleeping bag blankets and stowed our clothes on the shelf.

Further up the path from our cabin was our own “outhouse with a view”.

As I wandered back towards the central hall, I heard a familiar tapping from the forest. A hairy woodpecker was working its way up an old hemlock.

As the sky darkened, we chopped vegetables, sautéed mushrooms and barbecued steak. Peter joined us for dinner by candelight.

It had been one of the most magical of days: a very special opportunity to share a little slice of this majestic part of Canada. After washing the dishes in water heated on the woodstove, we said good night and headed up the path toward our cabins. It was time for bed.

***********

To enquire about booking a trip to Cougar Annie’s Garden and the Temperate Rainforest Study Centre, visit the Boat Basin Foundation Website.