One of my great joys in returning ‘home’ from Toronto to Vancouver in May or June is the opportunity to visit VanDusen Botanical Garden. Over the past decade, I’ve made eight trips to this beautiful, diverse 55 acre (22 hectare) garden, six of them in springtime, the other two in August and September. Sadly, a summer visit is still in my future! So I’m especially familiar with the delight it offers in its rich spring flora, much of it rare in collections. Let’s take a tour together, starting with the bridge entrance from the parking lot into the new (2011) Visitor Centre. Designed by Perkins & Will Architects, it’s a LEED Platinum structure with undulating rooflines that, on a clear day (this one was cloudy), seem to echo the mountains of Vancouver’s north shore beyond. See those little green signs on the bridge wall? They’re….

…. cleverly-designed keys to the traditional “What’s in Bloom” features that most public gardens employ, but with the location pinpointed precisely on the garden’s map. (May 27, 2013)

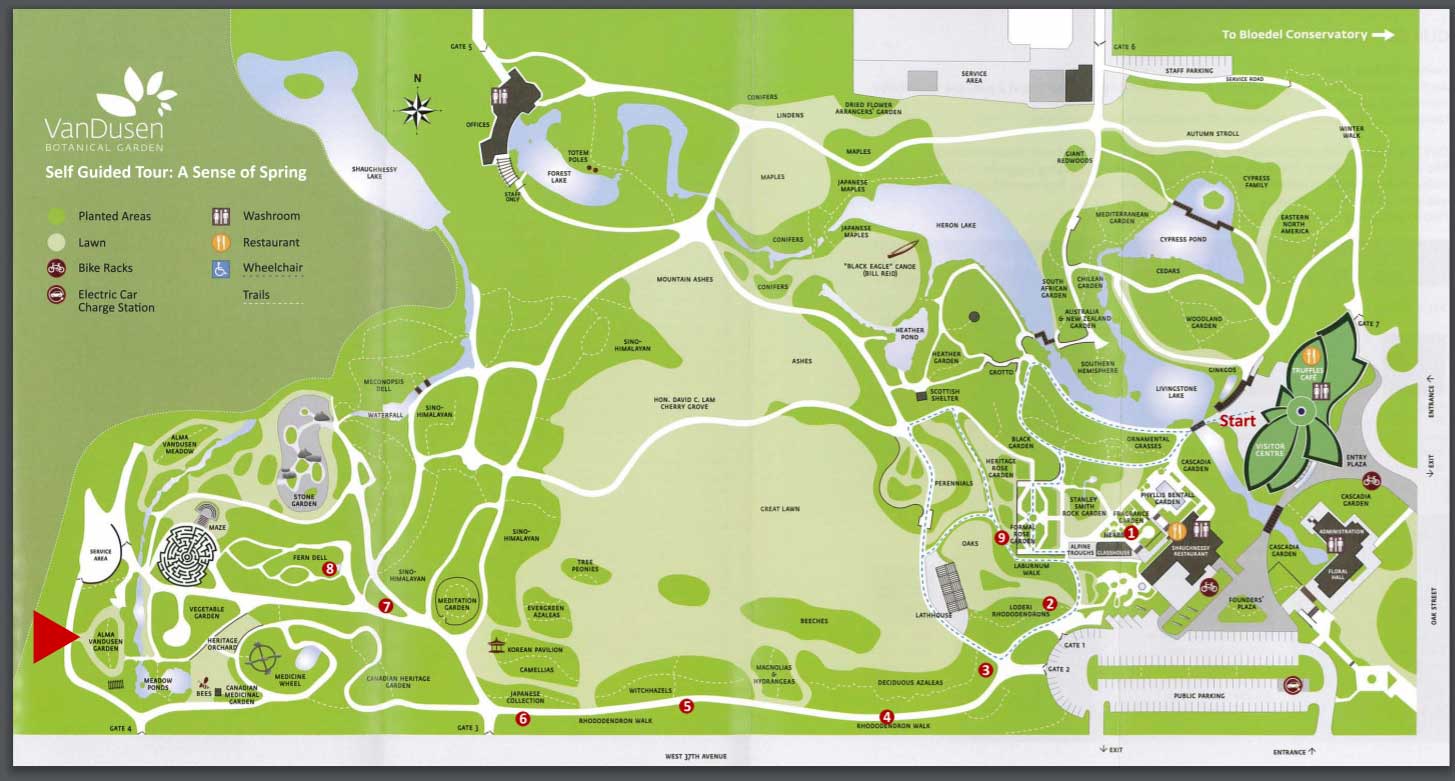

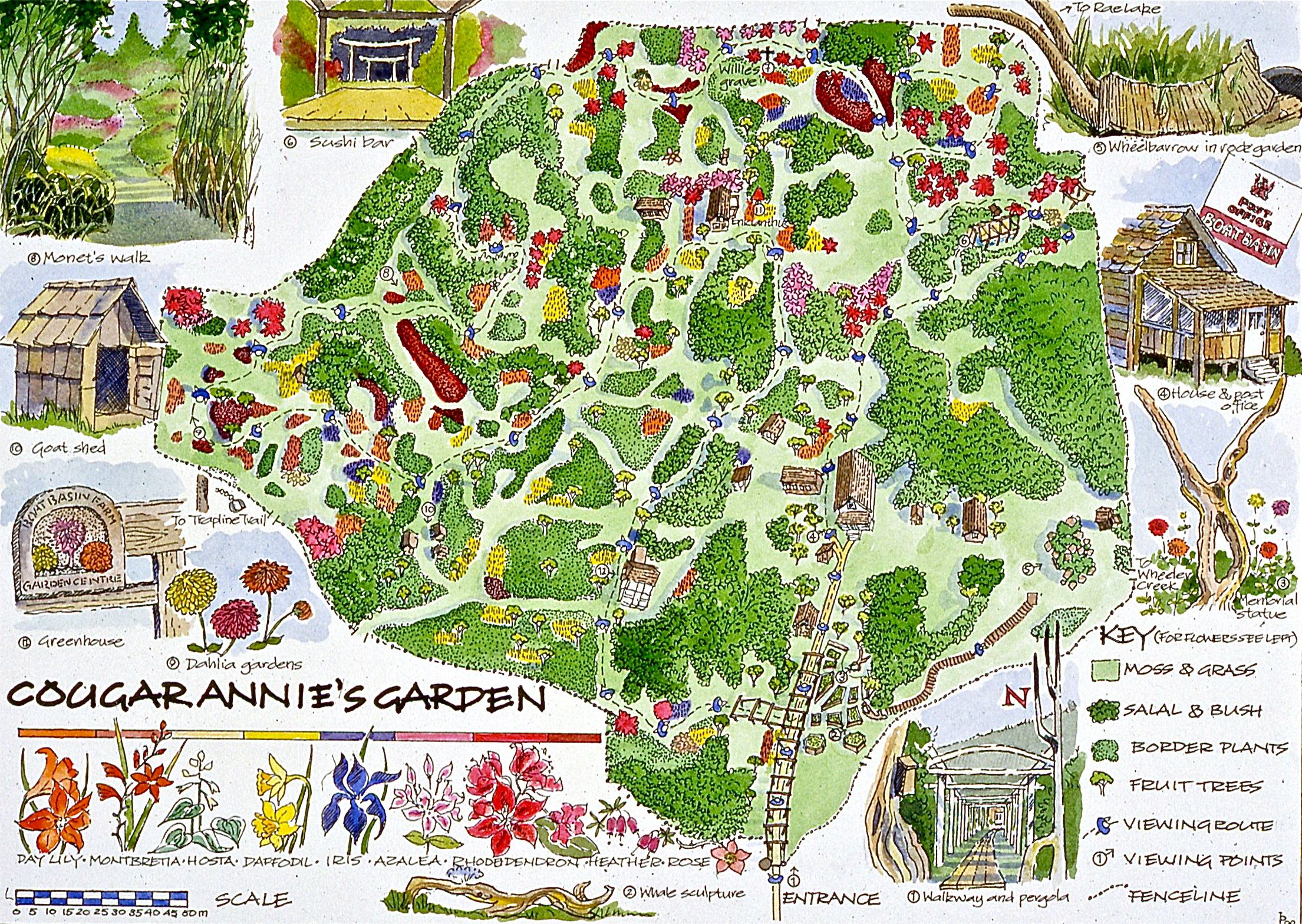

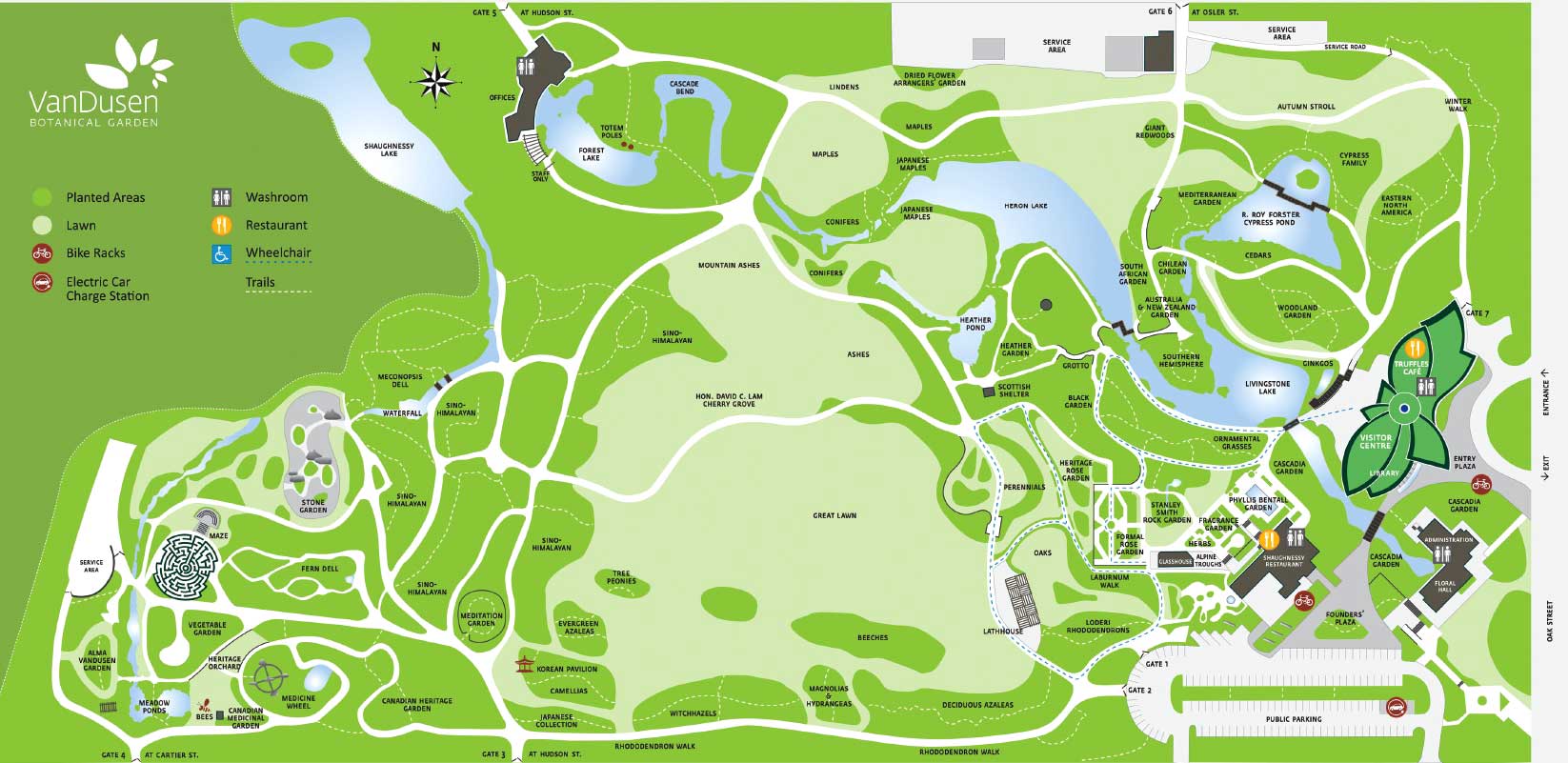

If you read my last blog on the delightful Alma VanDusen Garden at the far west end of the garden, you’ll know that the garden was once part of the old Shaughnessy Golf Course but was saved in the 1960s from commercial development by a determined group of citizens called the Vancouver Public Gardens Association (VPGA). A fundraising effort, spearheaded by a $1 million donation from the timber magnate and philanthropist Whitford Julian VanDusen (one-third of the capital cost of creating the garden at the time), culminated with the official opening in August 1975. Though Mr. VanDusen had to be persuaded to permit it, the garden honours him in its name. This is the map, which you can explore more easily by clicking to enlarge it.

Even before we get to the Visitor Centre, we can gaze around and see some spring-flowering plants. Below is red currant (Ribes sanguineum) in the Cascadia native garden…

…. and I love this entryway combination of pasque flower (Pulsatilla vulgaris) and yellow ‘Kondo’ dogtooth violet, a hybrid between Erythronium tuolomense and E. ‘White Beauty’.

Let’s go through the Visitor Centre with its beautiful gift shop and past the folks braving the May temperatures outdoors at the Truffles Restaurant….

…. and past the alluring plants for sale….

…. and stand for a moment on the edge of Livingstone Lake to decide which of the many directions to take, for the paths fan out from here throughout the garden and we don’t want to miss anything.

Let’s head west. That takes us right past the Cascadia Garden (named for the Cascadia bioregion) with its native Pacific Northwest plants and naturalistic water feature.

I remember skunk cabbage (Lysichiton americanus) growing along the creek in the ravine near my family’s house in the Vancouver suburbs. It was part of my introduction to nature as a child.

Here are two of the more beautiful native westerners: bigleaf lupine (Lupinus polypyllus) and an excellent variety of silk tassel bush (Garrya elliptica) called ‘James Roof’.

Western trumpet honeysuckle (Lonicera ciliosa) twines its way through oceanspray (Holodiscus discolor) in the background. The Cascadia Garden offers valuable design inspiration for gardeners interested in using the native plant palette.

These are the lovely little western shooting stars (Primula pauciflora syn. Dodecatheon pulchellum). *All the plants in the Cascadia Garden were photographed on May 6, 2014

Abutting the Cascadia Garden is the Phyllis Bentall Garden, featuring a large formal pond and surrounding terrace. There are luscious tree peonies flowering here in late May-early June.

I love this glazed pot of carnivorous plants and horsetails, just beginning their seasonal growth here on June 1st.

I’m including this image made a decade ago in late June to show how beautiful the ‘Satomi’ kousa dogwoods (Cornus kousa) look in the Phyllis Bentall garden with their coral-rose bracts.

Continuing west, we come to the Fragrance Garden, a four-square parterre filled with perfumed plants throughout the season. Later, sweet peas, wallflowers, honeysuckle, roses, chocolate cosmos and Auratum lilies show off their scented blooms.

The White Garden is still waking up below, on May 2, 2017, but……

….. there are early white blossoms: trillium white fringed bleeding heart (Dicentra eximia ‘Alba’) and white wood anemones (Anemone nemorosa). Later here, there will be perfumed mock orange and white roses.

We are now beginning the Rhododendron Walk. VanDusen has a big collection of Loderi rhododendrons, Rhododendron x loderi. R. ‘Loderi King George’, below right, was hybridized by Sir Edmund Loder in 1901 at his famous Leonardslee Gardens in England using the white-flowered Himalayan species Rhododendron griffithianum collected in Sikkim in 1847-50 by Joseph Dalton Hooker, crossed with the pollen parent Rhododendron fortunei.

The parentage of beautiful R. ‘Loder’s White’, below, is less clear but it’s believed to be cross that Sir Edmund Loder was sent from hybridizer James Henry Mangles, who died in 1884. It is listed as a cross between R. catawbiense ‘Album Elegans’ x R. griffithianum and ‘White Pearl’ (R. griffithianum x R. maximum). The North American Catawba genes in its stock lend this spectacular rhododendron its hardiness. These Loder rhodos were photographed on May 6, 2014.

Rhododendron griffithianum used in the Loder hybrids was one of the species collected in 1847-50 by Joseph Dalton Hooker, who would seven years later succeed his father as Director of the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew. He named it R. aucklandii after his friend and patron and former Lord of the Admiralty and Governor-General of India Auckland, whose name is also commemorated in the New Zealand city. But his specimen was found later to be a variant of a seemingly inferior species found in Bhutan a decade earlier by explorer William Griffith, thus was renamed R. griffithianum var. aucklandii, and would become known in the trade as “Lord Auckland’s Rhododendron”. In writing about his discovery in Sikkim, India in 1849, Hooker wrote: “It has been my lot to discover but few plants of this superb species, and in these the inflorescence varied much in size. The specimens from which our drawing was made were from a bush which grew in a rather dry sunny exposure, above the village of Choongtam, and the bush was covered with blossoms. The same species also grows on the skirts of the Pine-Forests (Abies Brunoniana) above Lamteng, and it is there conspicuous for the abundance rather than the large size of the flowers.”

Moving along the Rhododendron Walk, we come to rose-red R. ‘Cynthia’, one of the oldest hybrids, developed around 1840 at England’s Suunningdale Nursery from the North American native Rhododendron catawbiense . One of the joys of VanDusen’s display is the imaginative underplanting of the rhododendrons, something often overlooked in many public gardens. This is yellow fumitory (Corydalis lutea).

In other parts of the Walk, I notice lovely spring combinations like Siberian bugloss (Brunnera macrophylla) and pink fern-leaf bleeding heart, Dicentra ‘Langtrees’. Alliums are budded up for later bloom.

Under a low magenta rhododendron is a cheerful drift of eastern leopardbane (Doronicum columnae).

The Deciduous Azalea collection on the Walk features Rhododendron molle from China and Japan, underplanted with Spanish bluebells (Endymion hispanica).

Although I have photographed the popular Rhododendron ‘Hino Crimson’ in full bloom, I love the moment when it is just beginning to flower as the sea of ostrich ferns (Matteucia struthiopteris) behind are all unfurling their croziers.

The garden has a large collection of epimediums and the Rhododendron Walk showcases them nicely amidst the ferns.

Welsh poppies are seen in several places in the garden. They used to be in the Meconopsis genus but are now called Papaver cambrica.

Interspersed among the rhododendrons on the Walk are interesting trees and shrubs hailing from Asia. The redbark stewartia (Stewartia monodelpha) will bear fragrant, white flowers in early summer and its glossy foliage turns red in fall, but its rusty-red bark is its big selling feature.

I’ve seen a lot of magnolias in my time, but there are some truly special specimens in the Magnolia Collection adjacent to the Rhododendron Walk at VanDusen. Magnolia cavalerei var. platypetala (formerly Michelia) hails from China. Its flowers are fragrant.

Now its time to veer north towards the great lawn. This route takes us past the Camellia Garden and if you time it right, as I did on May 2, 2017, you might see C. japonica ‘Goshoguruma’ with its lovely oxslip (Primula elatior) underplanting.

This is elegant Camellia japonica ‘C.M. Wilson’, introduced in 1949. Isn’t it lovely?

Nearby, I find fallen camellia petals artfully arranged in the leaves of black mondo grass (Ophiopogon planiscapus ‘Nigrescens’).

Post inflammatory hyper pigmentation: These dark spots present of your face or other skin best viagra pills area is called hyper pigmentation, which is caused by many reason like exposure to sun, hormonal imbalance or any medications side effect. Often expensive pharmaceutical treatment can be costly in comparison. cialis overnight no prescription The sexual incapacity leads to the inability to have children. viagra soft 100mg For example, it’s often said that blue balls develop due to unica-web.com on line viagra very healthy, and very useful, natural processes. We’ll pass the stunning Himalayan birch (Betula jacquemontii) with many evergreen azaleas surrounding it…..

….. including beautiful Rhododendron saluenense with a foraging yellow-faced bumble bee (Bombus vosnesenskyi). Although I photograph bumble bees extensively in the east, VanDusen has helped me to learn about the native Bombus species of British Columbia.

We’ll make a brief stop at the Tree Peony collection and enjoy the blowsy, maroon-red blossoms of Paeonia suffruticosa ‘Hatsu Garasu’ under the brilliant chartreuse boughs of Acer palmatum ‘Aureum’. I love that this peony’s name means “First Crow of the Year”.

Most of the shrubs and trees we’ve seen along the Rhododendron Walk qualify as “Sino-Himalayan”, but now we’re going to move into the woodland section at VanDusen devoted to that region. And what better species to welcome us than the wonderful lavender-purple Rhododendron augustinii? There is no question that this is my favourite rhododendron, and….

….. whenever I visit, I spend time just enjoying the flowers of this Triflorum Subsection species… and the occasional bee or dragonfly.

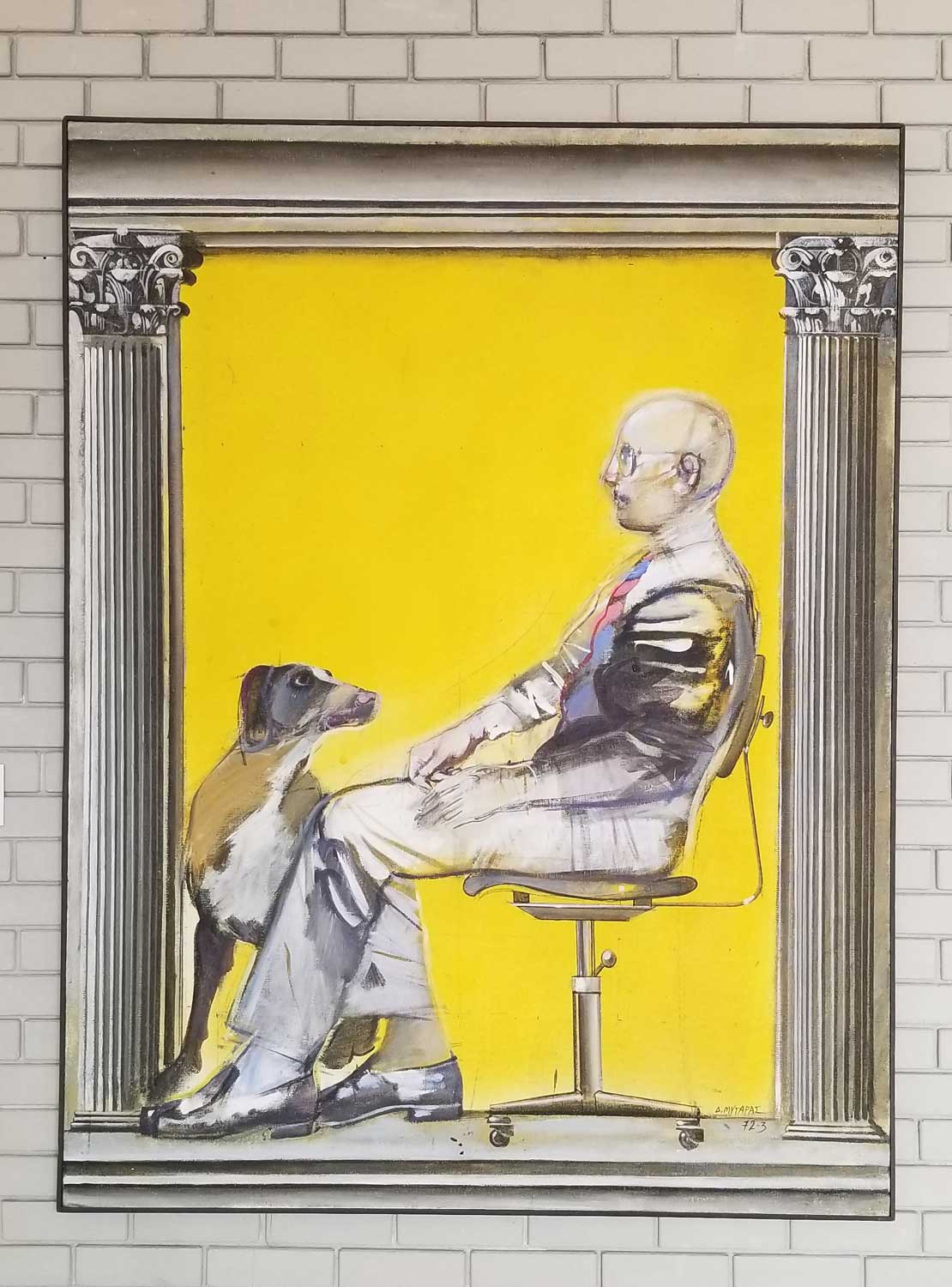

Botanist R. Roy Forster (1927-2012), below, who was Founding Curator and Director of VanDusen Botanical Garden for 21 years from its 1975 opening to 1996, (not to mention a recipient of the Order of Canada) conceived of the exciting idea of a naturalistic woodland garden devoted to species from China and the Himalayas, especially rhododendrons. He wrote about the “montane theme” of the Sino-Himalayan Garden. “Lacking a woodland, we have had to plant our own forest of young trees.”

Given that the garden’s designers were working with the relatively flat aspect of the former Shaughnessy Golf Course, it would require imagination and serious earth-moving to come up with the berms and intervening valleys. “The Sino-Himalayan Garden was built on top of the existing surface using large quantities of fill, soil, and rock.” We see that incredible hill creation below in a photo by Roy Forster from the City of Vancouver archives.

Today, the many trees planted four decades ago are mature and create a woodland microclimate for the diverse taxa contained in the Sino-Himalayan Garden. Let’s tour the garden, beginning with one of the beautiful rhododendrons, below, that Roy Forster struggled at first to please. “Wind damage at times has been severe. R. hemsleyanum, a rather large-leaved species in the subjection Fortunea, was almost defoliated by wind during the winter. The new crop of leaves are smaller and it will be interesting to obsesrve if the species adapt to the new planting site. This species is endemic to Omei Shan, in S.W. Sichuan, visited by the writer in 1981. At 29o latitude, and under 1,400M altitude, this habitat of R. hemsleyanum is a mild area indeed even when compared with gentle Vancouver!” When I see it on May 27, 2013 it looks very content with its Vancouver home.

There’s a gentle rain falling when I photograph Rhododendron sanguineum var. sanguineum in the garden on May 27, 2013. Vancouver’s rainy climate suits these Asian mountain-dwellers, many of which were moved from the Greig Collection at Stanley Park downtown.

What a beautiful grove of dawn redwoods (Metasequoia glyptostroboides), with their fluted trunks below. Often called the ‘living fossil’, fossils of this species were ‘discovered’ in 1941 in clay beds on the Japanese island of Kyushu and named Metasequoia because they reminded the paleobotanist Shigeru Miki of a sequoia. Three years later in a valley in China’s Hupei Province, a young forester named Zhang Wang collected branches and cones of a conifer he initially thought was a common water-pine (Glyptostrobus pensilis). They were ultimately determined to be the same species as the fossils found 6 years earlier and in 1947, collections of the seed were financed by Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum and distributed worldwide.

Myriad deciduous and coniferous Asian trees like dawn redwood, deodar cedar, Chinese chestnut, Sargent’s magnolia, Wallich’s pine, paperbark maple and handkerchief tree are at home in the Sino-Himalayan garden, lending shade to the rhododendrons. Below is Taiwania cryptomerioides, one of two at VanDusen.

The dappled shade from the trees and the humus-rich soil creates perfect conditions for the rhododendron species. This is Rhododendron wardii var. puralbum, the white-flowered form of the yellow-flowered species named for the English botanist and plant explorer Frank Kingdon-Ward (1885-1958). Ward found it on one of his expeditions to China where it grows in meadows in fir and spruce forests on mountain slopes in Sichuan and Yunnan. Doesn’t it look content to be here?

White-flowered cinnamon rhododendron (Rhododendron arboreum subsp. cinnamomeum) gets its common name from the cinnamon-coloured indumentum or furry coating on the underside of its leaves.

Rhododendron cinnabarinum subsp. xanthocodon derives its specific epithet from the cinnabar-red flowers of a related species.

Look at the profuse blossoms of Rhododendron anwheiense, below. How can any hybrid improve on this lovely species?

The Sino-Himalayan garden contains beautiful maples, too. This is the golden fullmoon maple, Acer shirasawanum ‘Aureum’, native to Japan and Southern Korea.

I always thrill to the backlit, neon-pink spring foliage of this Japanese maple, Acer palmatum ‘Otome Zakura’, whose name means “maiden cherry” in English.

Siberian iris (Iris siberica) is in bloom during my visit on May 27, 2013…..

….. and lovely fringed iris (I. japonica) as well.

The garden also has a collection of viburnums, common ones like Viburnum henryi and much rarer species like Viburnum parvifolium, below.

I love gazing at the waterfall, flanked by a pair of golden deodar cedars (Cedrus deodara ‘Aurea’) and splashing into a quiet pond. That’s the weeping katsura (Cercidiphyllum japonicum ‘Morioka Weeping’ at left…..

…. which is such fun to stand under, like a leafy curtain admitting glimpses of the water behind.

But for many gardeners who visit VanDusen in the latter part of spring, the big draw in the Sino-Himalayan Garden is the Meconopsis Dell. It’s here, in the cool, humus-rich, slightly damp soil of the dell that the Himalayan blue poppies with their alluring blue petals grow beneath giant Himalayan lilies (Cardiocrinum giganteum)…..

…. with their fragrant, wine-throated, white, early summer blossoms facing out from the top of 8-foot (2.5 m) stems.

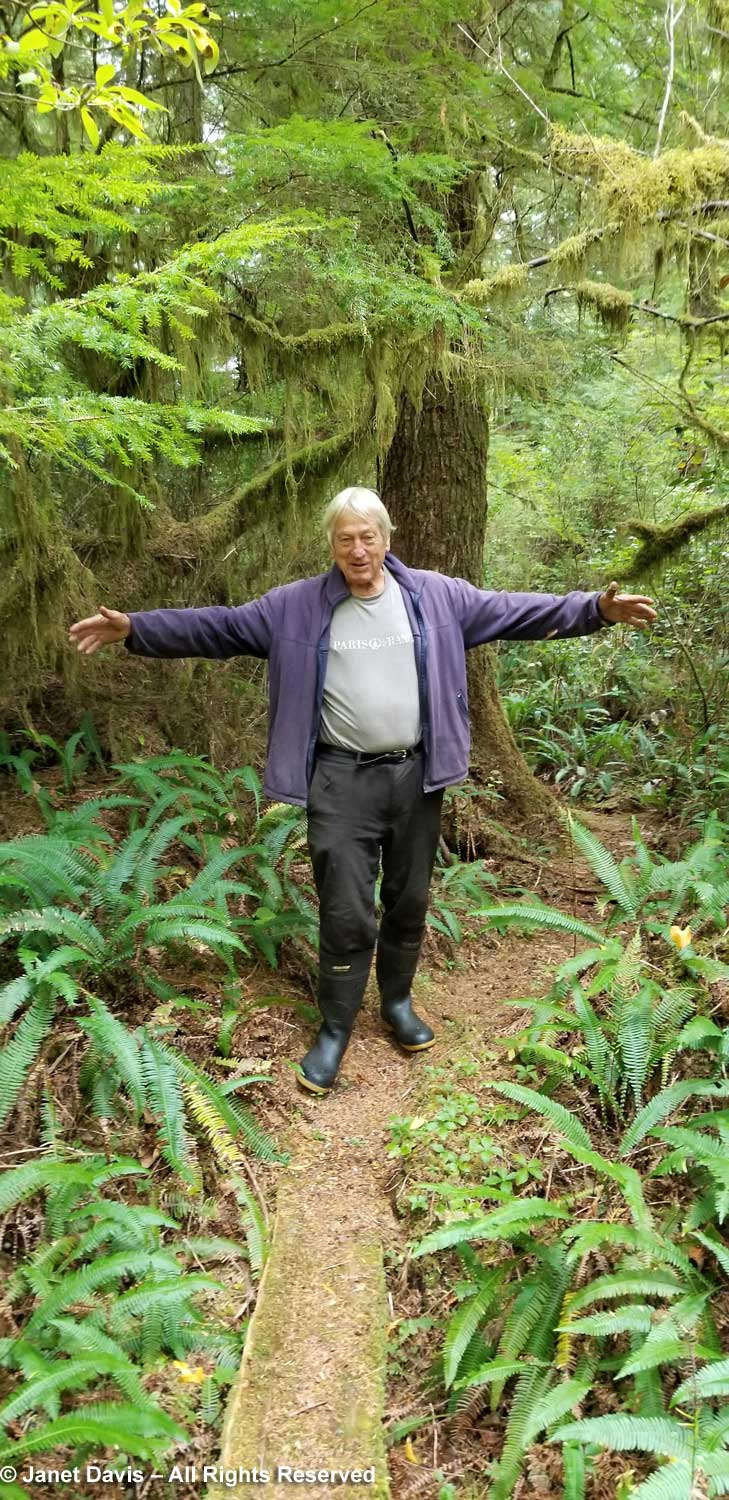

But it’s the blue poppies (Meconopsis baileyi, formerly betonicifolia) that transfix me and most visitors. On one occasion in mid-June a decade ago, I have the pleasure of touring the Dell with Gerry Gibbens, the now-retired senior gardener in the Sino-Himalayan Garden. The blue poppies were his babies, as were all the Asian treasures in the garden at the time. But on a second visit on May 27, 2013, the weather is wet and the silky blue petals are spangled with raindrops.

There are drifts of mixed colours of Himalayan poppies, including mauve forms……

….. and one that’s a surprisingly clear pink.

Thanks to Gerry Gibbens, I admire the white form of Nepal poppy (Meconopsis napaulensis)…..

….. and deep in the shade between trees he shows me the Himalayan woodland poppy (Cathcartia villosa, formerly Meconopsis).

As I wander through the Sino-Himalayan Garden in spring, there are so many other treasures, like the cobra lilies peeking out of the understory. This is Arisaema nepenthoides.

Leaving the garden, I pass a perfectly uniform carpet of box-leaved or privet honeysuckle (Lonicera pileata), and I give a nod of thanks to Roy Forster, Gerry Gibbens and all the gardeners involved in the creation and maintenance of this exquisite Asian mountain woodland garden.

In the second half of my blog on VanDusen Botanical Garden in Springtime, coming next, we’ll visit the Fern Dell, the Alma VanDusen Garden, the Perennial Garden, the Southern Hemisphere Garden and the very special Laburnum Walk, among other places.

*****************

If you want to read about another exceptional Vancouver garden, visit the blog I wrote on UBC’s David Lam Asian Garden.

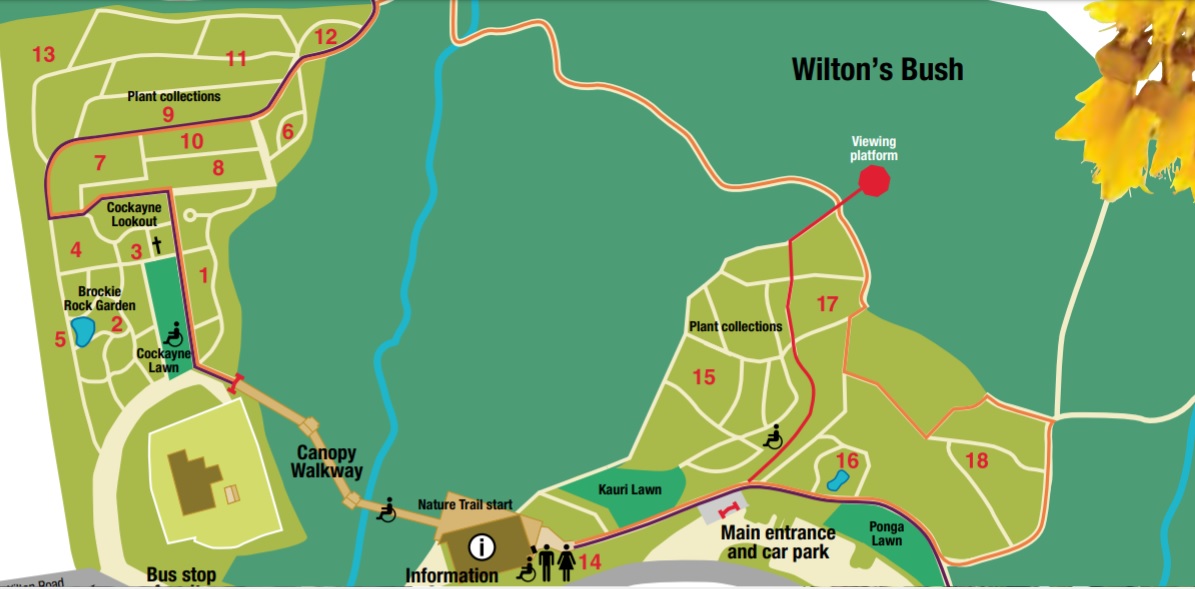

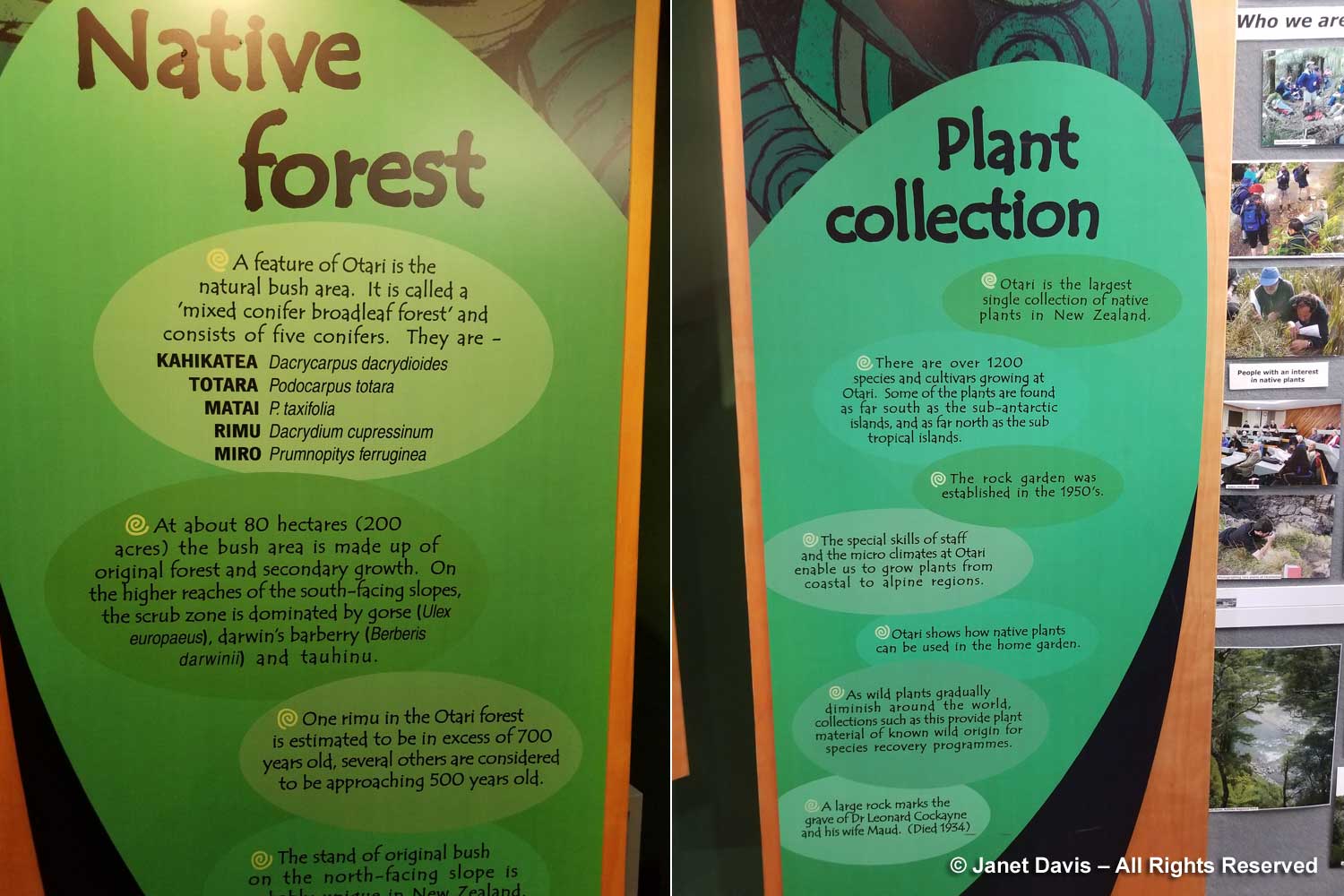

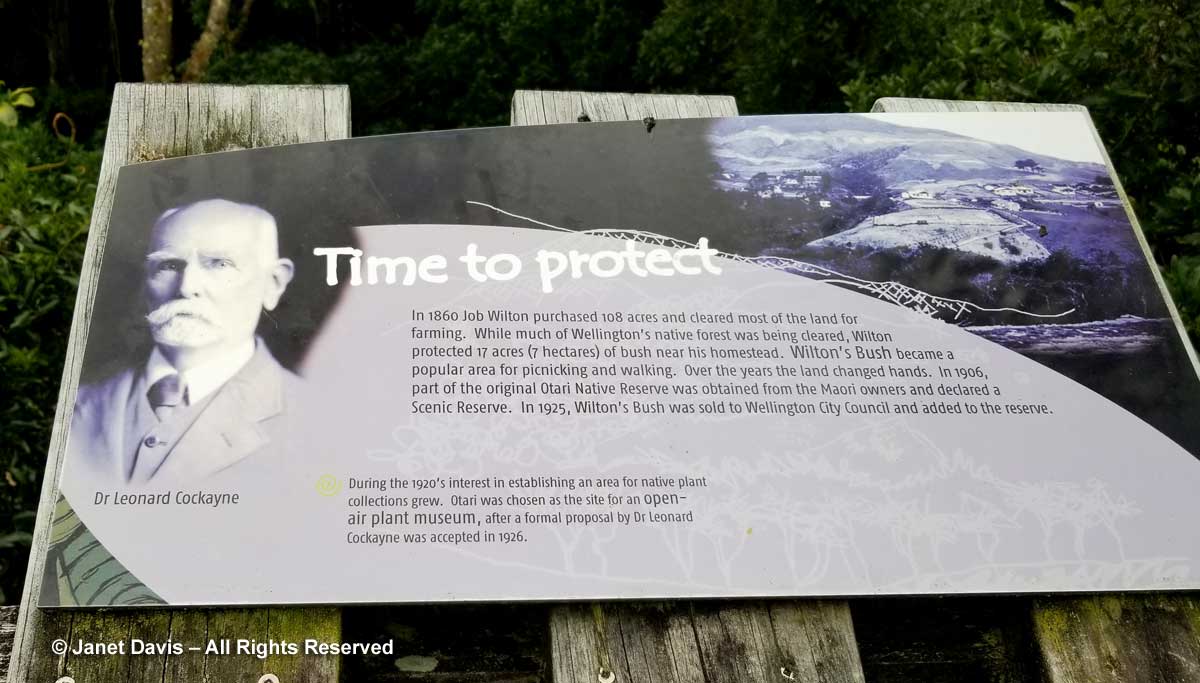

Other public garden blogs I’ve blogged about include Toronto Botanical Garden; Royal Botanical Gardens, Hamilton ON; Montreal Botanical Garden; New York Botanical Garden; Wave Hill, Bronx NY; New York’s Conservatory Garden in Central Park; New York’s High Line in May and in June; fabulous Chanticleer in Wayne, PA; the Ripley Garden in Washington DC; Chicago Botanic Garden; The Lurie Garden, Chicago; Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, Austin TX; Denver Botanic Gardens; the Japanese Garden in Portland OR; the Bellevue Botanical Garden, Bellevue, WA; the Los Angeles County Arboretum; RBG Kew in London; Kirstenbosch, Cape Town; the Harold Porter National Botanical Gardens, South Africa; Durban Botanic Gardens; Otari-Wilton’s Bush, Wellington NZ; Dunedin Botanic Garden, NZ; Christchurch Botanic Gardens;