Somehow, when I started writing professionally about gardens and plants way back in 1988 as my youngest child headed off to first grade, I did not think I’d still be as charmed by the Goddess Flora as I continue to be today. Especially given that my little first grader just turned 40 this spring and has a husband and three kids. Her three older brothers are in their 40s and 50s (the youngest gets married in Tuscany in exactly one month) and their mom – yes, me – is turning 75 today! When I was a young woman, I would have considered someone who’d reached my age as “elderly”. Funny thing – now I don’t! So Janet’s 19th fairy crown for August 10th is filled with fruitfulness – literally, the fruits and seeds of my meadows and wild places here at the cottage on Lake Muskoka and the fruits of a wonderful family life gathered over the past 45 years.

My family is very understanding: most have worn fairy crowns at one time or other. Here are my two older grandchildren getting their own custom crowns for my 74th birthday (photo by my son-in-law)…..

…… and posing with their younger brother, mom and me (aka “Nana”).

But it’s a longstanding tradition, even before I started my season-long parade of fairy crowns. Here’s my daughter 11 years ago with what we could find growing wild….

….. and my granddaughter with weedy bits from the front boulevard at their home, sweet violets and dandelions….

….. and my older grandson looking positively angelic.

My youngest grandson wore a happy smile when I asked him to pose with his crown.

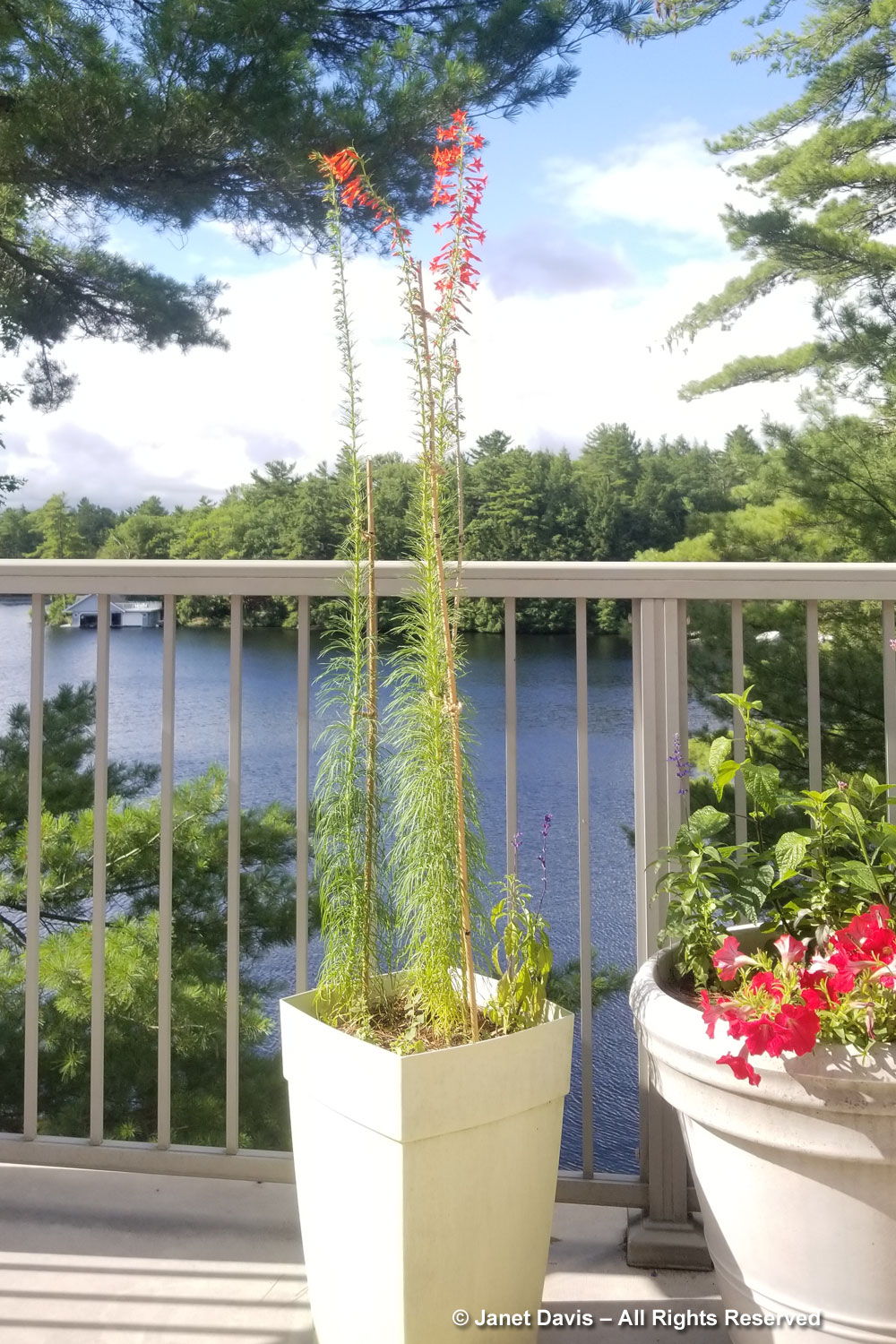

As for my own crown, it represents a different way of gardening here at the cottage, one I intentionally chose to pursue twenty years ago. There would be some places (mostly on our steep hillside) for the wild plants of the forest, and wildish meadows where favourite perennials, mostly native, would be free to grow, wander and seed themselves. There would be NO WEEDING. So, woven within my crown are native fruits, including Allegheny blackberry (Rubus allegheniensis).

Down by the lake are black huckleberries (Gaylussacia baccata) which are a little seedy, but fun to eat in late summer. And they don’t suffer fruit loss in droughts like the wild lowbush blueberries on our property.

Though neither of the above grow in quantities sufficient to gather enough to bake more than a pie or a dozen muffins, it is rewarding to pick a handful and understand that these have grown by this lake and sustained native people here, as well as the local fauna, for hundreds or thousands of years.

Staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina) is our most fruitful species, and I think its abundance is why I don’t suffer much deer damage to my “pretty” plants. White-tail deer love to browse on the branches and I see evidence of that all the way up our hillside.

Last summer, I even made a gin from my sumac blossoms. That’s it in the centre, flanked by blueberry and cranberry gins. I think in the final analysis it was my favourite flavour: a little bit lemony with something herbal as a side note. Unusual but tasty.

There are floral fruits in my birthday fairy crown too, including the pods of lupine, below….

….. and the dark fruit of blue false indigo (Baptisia australis), below….

….. and foxglove penstemon (P. digitalis), below. One of my very favourite plants for early summer – and a great bumble bee lure – it has very tough fruits, i.e. “capsules”, so when I harvest them after they’ve dried, I use pliers to crush them to avoid cutting my fingers.

Hiding in my crown is a little mushroom, but August is generally early for mushrooms on Lake Muskoka unless it’s a super-rainy month. However, give it a month or so and the mushroom show in this part of Ontario is spectacular. In fact, one year when we hosted our hiking group at the cottage, I hired a mushroom specialist to tour us around the forest. I think we found 38 species that day, using his keys.

There will be a little dock party today with relatives around the lake. Pretty sure there’ll be cupcakes, too and grandkids’ homemade gifts. And of course there are lots of flowers in bloom in the meadows and beds now and I will make sure we have some on hand as I turn… 75. I just need to get used to saying it. It shouldn’t be that hard, right?

******

There were 18 fairy crowns before this one. Here they are!

#1 – Spring Awakening

#2 – Little Blossoms for Easter

#3 – The Perfume of Hyacinths

#4 – Spring Bulb Extravaganza

#5 – A Crabapple Requiem

#6 – Shady Lady

#7 – Columbines & Wild Strawberries on Lake Muskoka

#8 – Lilac, Dogwood & Alliums

#9 – Borrowed Scenery & an Azalea for Mom

#10 – June Blues on Lake Muskoka

#11 – Sage & Catmint for the Bees

#12 – Penstemons & Coreopsis in Muskoka

#13 – Ditch Lilies & Serviceberries

#14 – Golden Yarrow & Orange Milkweed

#15 – Echinacea & Clematis

#16 – A Czech-German-All American Blackeyed Susan

#17- Beebalm & Yellow Daisies at the Lake

#18- Russian Sage & Blazing Stars