Back in late June, I noticed the odd dark, spotted caterpillar here and there on our property on Lake Muskoka, 2-1/2 hours north of Toronto. On July 2nd, my son informed me I had a caterpillar on my leg. Looking down, I saw a European gypsy moth caterpillar (Lymantria dispar) resting on my pink capris. Knowing how I love photographing insects, my son actually said, “Or… did you put it there?” Uh, no! Recalling that the bristly caterpillar can produce an allergic dermatitis, I used a paper towel to remove it and toss it outdoors. Perhaps it was a sign, a portent of the next month as I discovered the extent to which the caterpillars had laid future claim to the trees – mostly oaks and white pines – on our 2 acre property. Though I had heard from friends about massive defoliation of poplars and other hardwood trees in the farming areas northwest of Toronto, I could detect little or no damage where we were. Yet. But given the large numbers of female moths and egg masses I found in July, it seems that the caterpillars on Lake Muskoka were just preparing for their assault for 2021, a cyclical peak that normally occurs every 8-10 years..

This last stage of the caterpillar’s spring/early summer existence is quite beautiful, if destructive insects can be said to be beautiful. The studio shot below is by Dr. Didier Descouens of France, via Creative Commons.

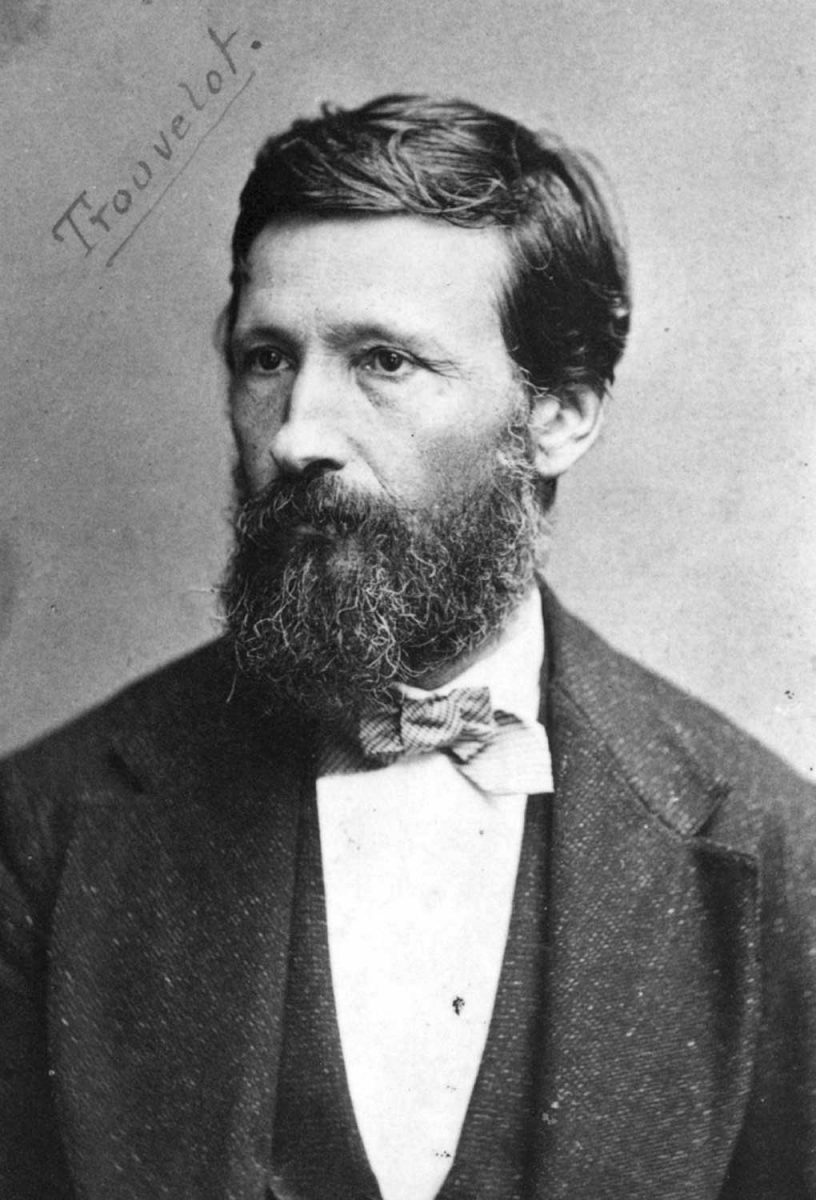

“France” and “gypsy moth” have another connection: the scenario that saw an invasive forest pest introduced accidentally by a French artist/entomologist/astronomer named Etienne Leopold Trouvelot.

He was not yet 30 when he emigrated from France in 1857 and settled in the house below on Myrtle Street in Medford, Massachusetts. For a decade, he attempted to raise caterpillars for silkworms, especially those of the North American native Polyphemus moth, a giant silk moth with a 6-inch wingspan. Silkworm experimentation was something of a fad at that time and it was noted that at one time he had a million larvae in a netted woodland behind his house. Sometime in the late 1860s, he travelled to Europe and returned with gypsy moth eggs, evidently hoping to hybridize them with natives to be disease-resistant. Around 1868-69, some of the eggs or larvae reportedly blew out his window, a fact to which he confessed in professional circles. However, there was no USDA in those days, no means of inspecting animal or plant species imported from other countries. It took a few decades for their population to build but by 1889 Medford’s trees were being defoliated by a caterpillar that required massive eradication strategies. And, as we know, that hasn’t worked very well as gypsy moths have made their way north and west in North America, decimating forests as they go. As for Trouvelot, he gave up on moth-rearing and in 1872 was invited to join Harvard College’s astronomy department, where he became renowned for his celestial illustrations and published some fifty papers. By the time he returned to France in 1882, his gypsy moths were well into their reign of terror in Medford.

At Lake Muskoka, we have a lot of oaks. They grow all around our cottage, a mix of the predominant red oak (Quercus rubra) and scrubby white oak (Quercus alba). It’s on the oaks that we see blue jays cracking acorns and woodpeckers, flickers, thrashers and nuthatches scaling the trunks looking for insects. Red-eye vireos nest in oaks. In fact, as entomology professor and best-selling author Doug Tallamy says in his book Bringing Nature Home, oaks are the best trees you can grow to sustain wildlife in your garden.

We have oaks up near our septic field….

…. and at the back of our cottage facing the little bay to the north of us.

I started to pay attention to the gypsy moths flying around. I checked the trunks of the oaks and found a few of the late-stage larval caterpillars….

…. and lots of the next stage — the reddish-brown pupae, below, the bigger ones being the female moth, smaller ones the males.

Some caterpillars had even pupated on the leaves of oaks.

I looked at the sign I had made for our cottage displaying the big white oak trunk in the centre of our main room….

…. and lifted it up to find pupae on the wall behind.

I even found a pupa on a window frame.

I began to inspect the trees and found a female gypsy moth newly eclosed from the pupa. Isn’t she lovely? (Or she would be, if she wasn’t the mother of 200-500 destructive leaf-eaters.)

Down near the lake, on the bark of trees we had previously wrapped with wire mesh to protect from the teeth of beavers, I found a female moth hanging onto the wire.

Not long after the female moth emerges from the pupa, she produces a pheromone which attracts male moths, sometimes more than one at a time.

Male moths spend their lives flying around looking for females, while non-flying female moths often walk upon the bark of the tree, first to find a suitable place to attract males; later, after copulation, she might walk about to find a place to lay her fertilized eggs and cover them with hairs.

Once she has fulfilled her role and produced the distinctive, rusty-brown egg mass, the female falls off the tree and dies. Though many authorities recommend removing or spraying the egg mass in autumn or winter, I realized that it was much easier to try to control the egg masses while the female was still clearly visible. Our hillside is often under many inches of snow by November, and I didn’t relish slipping and sliding over rocks trying to scrape off egg masses.

Where I saw unhatched pupae, I used a stick to squish the bigger female ones.

Broadleaved trees defoliated by gypsy moth caterpillars in spring will refoliate in mid-summer. Provided there is enough rain, the trees should survive. But conifers do not have this ability, so it was particularly depressing to find a few white pine trees hosting egg masses. However, I have read research that indicates that white pines are very poor hosts for larval development, compared to oaks.

For the female moths and egg masses, I made up my own horticultural oil, aka “dormant oil”. There are many recipes on the internet with various ingredients, but I mixed ½ cup of vegetable oil with 2 tablespoons of liquid dish soap. I then used a tablespoon or two of this concentrated mix in 2 cups of water to make my spray. My oil will not damage plants but is intended to suffocate the eggs. (You can also buy horticultural/dormant oil formulations at garden centres and big box stores; these generally use refined paraffinic oils.)

It was satisfying to spray the female moth and egg mass. I also used a stick to squish the moth.

I discovered that moths often favoured a particular tree, where I would find ten or more clustered together.’

This moth had made her nesting spot in the centre of a patch of moss high up an oak trunk. It became my challenge to figure out a way to reach these high locations without killing myself on a ladder.

I adapted an 11-foot telescoping pole used to change the pot lights on our high cottage ceiling, tying a sponge to the mechanism and soaking that in the diluted horticural oil.

That allowed me to reach moths and egg masses some 16 feet up a trunk….

…. soaking the moth and her egg mass with the saturated sponge, below. For the moths further up on trees, I can only keep my fingers crossed that next winter will be severe enough to damage the eggs. In observations in Michigan, it was found that eggs on southern and western aspects were much less likely to survive severe winter temperature swings than those on northern and eastern aspects.

Some of the literature on gypsy moth control recommends removing litter under trees. That might work in suburban or urban yards, but it isn’t realistic or desirable in a forest like ours, below, where a diverse understory supports all kinds of insects, birds and other life.

In fact, while moving around under my trees looking for moths, I was rewarded with the sight of two interesting parasitic (non-chlorophyll-producing) plants that are sustained by the mycorrhizae on the roots of oaks: Indian pipe or ghost plant (Monotropa uniflora), below….

… and bear corn or American cancer-root (Conopholis americana).

I did a lot of videography while I was preparing this blog, and made an 11-minute video that provides a little more information.

Though some panicked property owners and civic officials call for aerial spraying of the biological control agent Bacillus thuringiensis kurstaki or Btk in late spring when the caterpillars begin their climb into tree canopies, it is non-specific and will kill the larval stage of all lepidopterans (caterpillars of moths and butterflies) active at that time, including many native insects that co-evolved with our native plants and feed our birds. Some will say it’s not going to harm the summer caterpillars of monarch or swallowtail butterflies, but that is to ignore a vast web of life that exists in our environment without us noticing.

If you’ve made it this far, you’ll be happy to know I have had rewarding experiences with native caterpillars in the past, especially the monarch love affair I wrote about in last summer’s blog “Bella and Bianca: Our Monarch Chrysalis Summer”. I only hope that the steps I’ve taken this summer will curtail some of the damage we can expect to see next spring. I’ll be thinking about that as I gaze up at our beautiful oaks when their leaves change to russet and scarlet this autumn. And I’ll report back next year.

Well done…interesting and informative.There is much for all of us to do.

One of our small oaks (4 ft.) has been decimated all leaves off.

Sad situaton but mostly fear the beautiful pines. I will try using the detergent and old in a spray. Thanks! The world is in trouble also, with climate change, increases in temperature… which also bring ing more mosquitoes who love higher temps.

Warmly, Marjut

Marjut – The spray is for the egg masses, once they are laid by the females later this summer, not for the current caterpillars themselves. There are strategies you can employ for them, however, Look up the burlap trunk wrap, which must be emptied daily. Best of luck.

Thanks for this write up. After spending the morning picking caterpillars and pupae (drowning them in soapy water) off my defoliated apple trees, I’m keen to get on top of the population for next year without harming all the native insects.

I am also on the edge of a forest, so I know it’s going to be an ongoing process.

Sandy… it was satisfying to do but I’m not sure how successful I was overall. For the hundreds of egg masses I destroyed, we’re still getting slammed here in June. Our oak hillside looks like February…