My 16th Fairy Crown for August 1st is a simple affair featuring just one plant: Rudbeckia fulgida var. sullivantii ‘Goldsturm’. If it looks a little lonely, it’s because its normal garden partners had either already been fairy crown ingredients (hello, purple coneflower) or weren’t quite in flower yet (liatris and perovskia). But I think it gives a rather regal impression, as if a fairy queen had landed near a midwest cornfield and tried on the local wildflowers for size.

Speaking of American wildflowers, this particular blackeyed susan – or shining coneflower, as it is also known – is possibly the most widely-grown species of any North American taxon, given that it made its way back to our shores via the kind of circuitous route that features botanical discoveries, far-flung horticultural relationships, European plant propagation and the success of the American public relations machine.

I don’t always look at nomenclature, but since my fairy crown only has one ingredient, let’s explore this one. Rudbeckia. Even though it is a North American genus in the Asteraceae family, Carl Linnaeus – who in 1753 in his Species Plantarum assigned binomial names to all known plants — knew of it from the earliest plant explorers to leave Europe and gather new world seeds, cuttings and herbarium specimens. He named the genus after his Swedish mentor and patron, Olof Rudbeck the Younger (1860-1740), professor of botany at Uppsala University whose children he had also tutored.

In his dedication, Linnaeus wrote: “So long as the earth shall survive and as each spring shall see it covered with flowers, the Rudbeckia will preserve your glorious name. I have chosen a noble plant in order to recall your merits and the services you have rendered, a tall one to give an idea of your stature, and I wanted it to be one which branched and which flowered and fruited freely, to show that you cultivated not only the sciences but also the humanities. Its rayed flowers will bear witness that you shone among savants like the sun among the stars; its perennial roots will remind us that each year sees you live again through new works. Pride of our gardens, the Rudbeckia will be cultivated throughout Europe and in distant lands where your revered name must long have been known. Accept this plant, not for what it is but for what it will become when it bears your name.” The “type species” representing the genus is biennial blackeyed susan (Rudbeckia hirta), below, which I wrote about in my “songscape” blog Brown Eyed Girl(s), honouring Van Morrison. The other two species named by Linnaeus are Rudbeckia laciniata and R. triloba. The remaining 22 species had other authors, with R. fulgida, i.e. orange coneflower being described by the Kew-based English botanist William Aiton (1731-1793).

But back to my crown now; the correct Latin name of the species is Rudbeckia fulgida var. sullivantii. Sullivant’s coneflower, native from New Jersey west to Illinois and south to North Carolina and Missouri. The taxon rank “var.” indicates a variation of orange coneflower that was either described by or honoured Ohio-based botanist William S. Sullivant (1803-73), below. He later became a renowned bryologist, or moss expert. Another popular native variant of orange coneflower is R. fulgida var. deamii.

At some point, seed of Sullivant’s coneflower made its way to Europe and the botanical garden of Austria’s University Graz. From there, it was distributed to Gebrueder Schütz who grew the plants at his nursery in the Czech Republic. In 1937, Heinrich Hagemann saw the “a glorious stand of the plants” there and brought them back to his boss, Karl Foerster, below, at his nursery in Potsdam, Germany. Foerster was so impressed with the plant’s floriferous nature that he gave it the cultivar name ‘Goldsturm’ (German for “gold storm”). World War II delayed its introduction to commerce until 1949 and by the 1970s it was being grown widely in Europe and North America.

Karl Foerster in his garden 28. September 1967

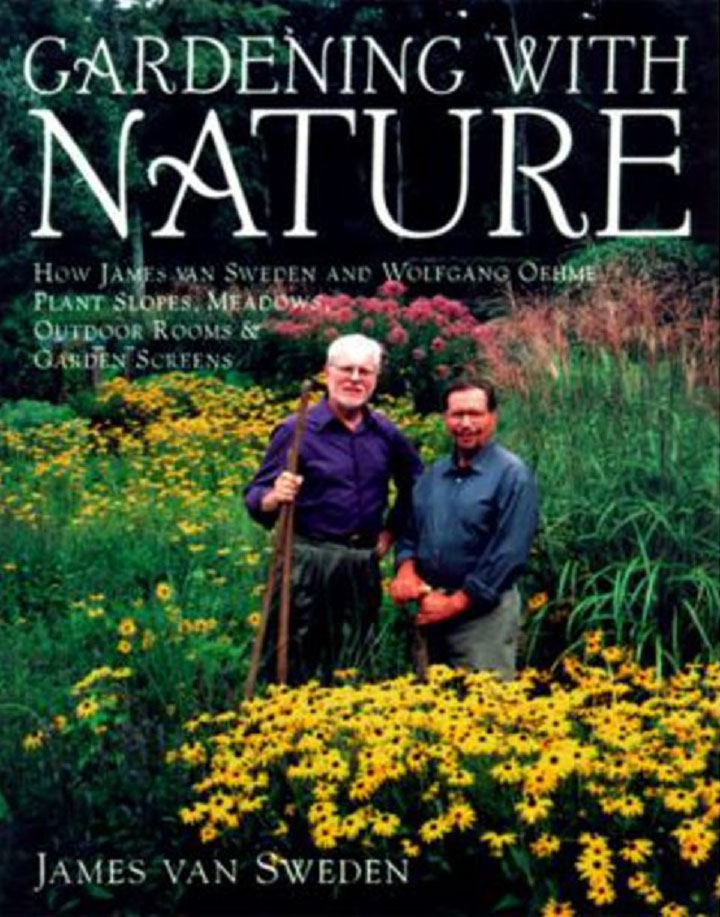

By the late 1970s, the German-born landscape architect Wolfgang Oehme and his partner James Van Sweden would use ‘Goldsturm’ along with ornamental grasses in large masses for their renowned “new American landscapes” inspired by the Great Plains. It was pictured with them on the cover of their 1997 book, ‘Gardening with Nature’.

Its popularity with American garden centres would result in it being named the 1999 Perennial Plant of the Year by the Perennial Plant Association (PPA). And many gardeners did what I have done, which is to mix it with purple coneflowers (Echinacea purpurea).

It is prominent in my front yard pollinator garden in Toronto…

…. where it is only moderately successful at attracting bees, including honey bees, because when echinacea is in flower, it plays second fiddle in the pollinator department.

Unlike biennial blackeyed susans (R. hirta) which flowers on single stems (and is in my next fairy crown!) the stems of ‘Goldsturm’ clump together and function as a mass of flowers 36 inches (90 cm) in height and 24 inches (60 cm) in width. It also likes richer soil and more moisture than than R. hirta.

In my garden it starts flowering soon after the echinacea begings to bloom and when the sedum ‘Autumn Joy’ is still green….

…… and continues flowering along with blue perovskia and other plants until the sedum turns red.

I love the Susans…Your pollinator garden is lovely. Once upon a time when I had more Susans in the garden I noticed that the little bees and the Skippers visited it more frequently than bumbles. I have a few Rudbeckia fulgida var fulgida with deeper green leaves and taller stems.

Thanks Gail. It was a fun little garden to make (with help from a landscape friend) but the echinaceas are muscling the other plants out of the way. Needs a little editing.

I love your whole story and the beautiful flowers in your garden. Thanks for sharing the story.

Thanks, Trudy. We don’t always focus on the history and taxonomy of our plants and this one seemed to call out for that.