During my September Garden Bloggers’ Fling in the Philadelphia area, my favourite small garden was Andrew Bunting’s delightful property in Swarthmore. Perhaps that’s no surprise, given that the owner is the Vice-President of Horticulture with the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society. Founded in 1827, the PHS is the oldest horticultural society in the U.S., responsible for the annual Philadelphia Flower Show as well as a host of endeavors including 120 community gardens; maintenance of public landscapes in the city and suburbs including museums, the art gallery and public squares; street tree programs; the 28-acre estate garden at Meadowbrook Farm; Landcare, in which vacant city lots are turned from blighted properties to neighbourhood parks; pop-up ephemeral gardens; and a program to train former convicts to be gardeners.

Since buying the house on its one-third acre in 1999, this garden is where Andrew has experimented with an eclectic roster of plants and an evolving approach to design – in fact, five redesigns in his time there. I especially loved seeing his home through the tall, wispy wands of ‘Skyracer’ purple moor grass (Molinia caerulea subsp. arundinacea), a grass that shines in my own garden in autumn. Beyond is a gravel garden bisected by a broad flagstone walk with a small patch of lawn that creates a nice balance of negative space, as well as lavenders and verbascums and other drought-tolerant plants, many native. A stone trough acts as a birdbath and a terracotta urn features a chartreuse explosion of colocasia (likely ‘Maui Gold’).

Arkansas bluestar (Amsonia hubrichtii) with its needle-like leaves is prominent in the front garden; its blue flowers are attractive in spring but its brilliant gold fall color gives it long-season appeal. Barely visible in the foliage is a wooden chair. Originally white, the front door and window shutters were painted gray, picking up the colors of the flagstone.

Behind the amsonia is Hydrangea paniculata ‘Limelight’ and, at left, willow-leaf spicebush (Lindera glauca var. salicifolia), which also has good autumn colour.

The vine around the door and on the house’s front wall is self-clinging Chinese silver-vein creeper (Parthenocissus henryana). I love the mailbox and house numbers.

My colour-tuned eye picked up the echo between the red glasses indoors and the big caladium and chartreuse-and-red coleus in Andrew’s windowbox.

Our time was limited and there was so much to see, but I could have spent hours studying the gravel garden, including many native plants like giant coneflower (Rudbeckia maxima), below. Andrew’s influences around gravel include Beth Chatto’s garden in England, the Gravel Garden designed by Lisa Roper at Chanticleer (see my latest blog here) and Jeff Epping’s work at Olbrich Gardens in Madison, Wisconsin. The gravel is 1/2 inch granite but Andrew says it’s more like 1/4 inch.

Here is native wild quinine (Parthenium integrifolium).

And American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana) with its vibrant violet fruit.

Andrew removed much of the original driveway beside the house which was too narrow for cars and turned it into a shady sideyard garden with a path leading to the old garage – which became a charming summerhouse. Those little purple flowers are Vernonia lettermannii ‘Iron Butterfly’, a good fall bloomer and, incidentally, a Pennsylvania Horticultural Society 2023 Gold Medal Plant Winner!

Turning the corner at the back of the house, I saw more evidence of a plantsman’s wonderland with assorted tropicals in pots and a potting bench topped by colourful annuals.

Andrew was holding court in the back garden, so I asked him to pose. His own history in horticulture is very deep. Even at a young age, he knew a career in gardening was in his future – and it relates to the name of his own garden. As he has written in an essay about becoming a gardener, “My grandfather farmed in southeastern Nebraska, just outside a little town called Belvidere. I loved those couple of weeks on the farm every summer. Something about that agrarian lifestyle resonated with me then, and still does today. I loved the crops in the field, my grandmother’s vegetable garden, and the smell of hay.” He did internships at the Morton Arboretum, Fairchild Tropical Garden and the Scott Arboretum, where he worked in the late 1980s for three years. In 1990 he visited more than a hundred gardens in England, meeting Rosemary Verey, Beth Chatto, Christopher Lloyd and working for a while at Penelope Hobhouse’s Tintinhull. That autumn, he travelled to New Zealand and worked for a designer for 3 months. Returning to Pennsylvania, he got a part-time position at Chanticleer as it was becoming a public garden, working there for 18 months while starting his own landscape business on the side. In 1993, he became curator of the Scott arboretum at Swarthmore College and stayed there for 22 years, until becoming Assistant Director and Director of Plant Collections at Chicago Botanic Garden in 2015.

I saw Andrew during a garden symposium in Chicago in 2018, below, when he spoke about how he directed the content and curation of CBG’s permanent plant collection. Next, a job offer at the Atlanta Botanic Garden arose and he became Vice-President of Horticulture and Plant Collections at Atlanta Botanic Garden, giving him the chance to grow broad-leaved plants. Then the opportunity at Pennsylvania Horticultural Society opened up and he returned to Swarthmore and the abundance of public gardens that make the Philadelphia area “America’s Garden Capital”.

When Andrew bought the house in 1999 the back yard was filled with a jungle of pokeweed. With the help of his landscape crew and a bobcat, he installed a 35 x 12 foot patio spanning the back of the house. It’s the perfect setting for a lush ‘garden room’ created with pots of banana, canna and palms. These tropicals get carried down to the cool, damp, cellar-like basement for winter through the entrance partially shown at left.

There are potted plants everywhere, many on vintage tables…..

…. and étageres.

Textural foliage combinations caught my eye, like this chartreuse sweet potato vine (Ipomoea batatas) with Euphorbia x martinii ‘Ascot Rainbow’ euphorbia and a fancy-leaved pelargonium.

There are bromeliads here too, like Portea petropolitana.

Most chairs in the garden were built by Chanticleer’s Dan Benarcik – and can actually be ordered custom online as kits or fully assembled! Note that the granite gravel has been used here, which Andrew says is a less expensive solution than flagstone paving. At right, you can see the entrance to the covered part of the summerhouse, aka the old garage.

So many artful touches here, combining with the rich plant palette to create a beautiful outdoor living space.

Let’s take a peek into the summerhouse, where a comfy leather sofa awaits. As Andrew once said in an online Masterclass chat with Noel Kingsbury and Annie Guilfoyle, many people in the Philadelphia area go to the New Jersey shore or the Poconos in summer, but he prefers his own garden – “less traffic and more access to gardening”. And I can imagine sitting in here behind the screen doors during a summer thunderstorm, candles lit, perhaps with a little glass of something tasty.

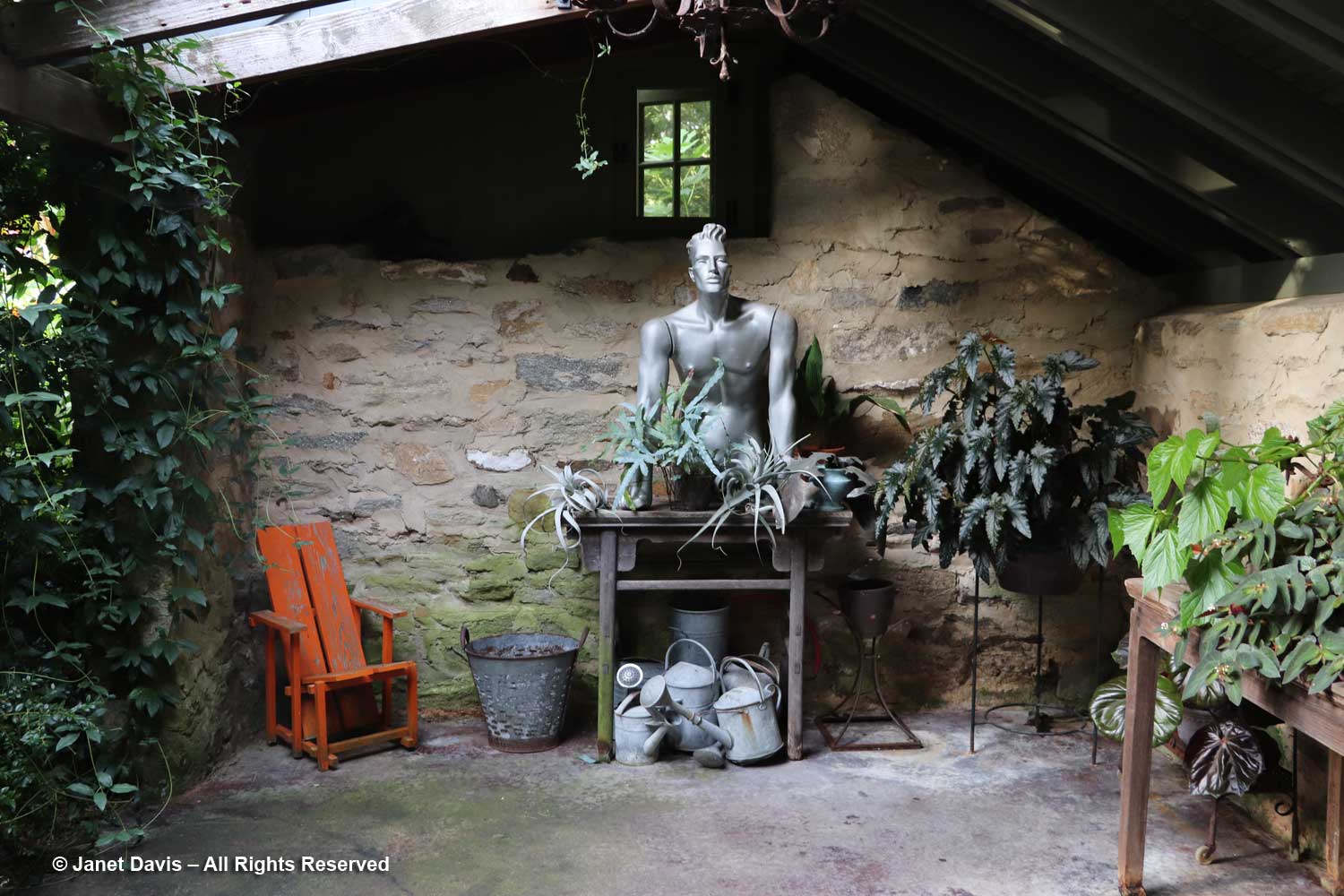

The back of the summerhouse is more open to the elements and features the perfect stage set. I don’t know what the silvery Adonis mannequin was once wearing on his sculpted torso, but I’m willing to bet it was Ralph Lauren, now nicely accented with tillandsias and begonias.

Nearby are more colocasias and blue Salvia guaranitica.

I loved all the seating (still more Dan Benarcik chairs), this time on a shady patio with a dining table.

Sometimes the seating is more about atmosphere and lichen-rich patina than it is about an actual place to sit.

In a shady spot at the back of the garden is a naturalistic pond because… every garden needs a little water.

I was sad not to have time to take a peek behind the back fence into the neighbour’s yard, where there’s an Andrew-designed large, shared quadrangle vegetable garden, but it was late in the season for veggies anyway. Mostly, I was happy that we were able to see this lovely garden in dry weather, since we were soon to find ourselves on the soaking end of Tropical Storm Ophelia.