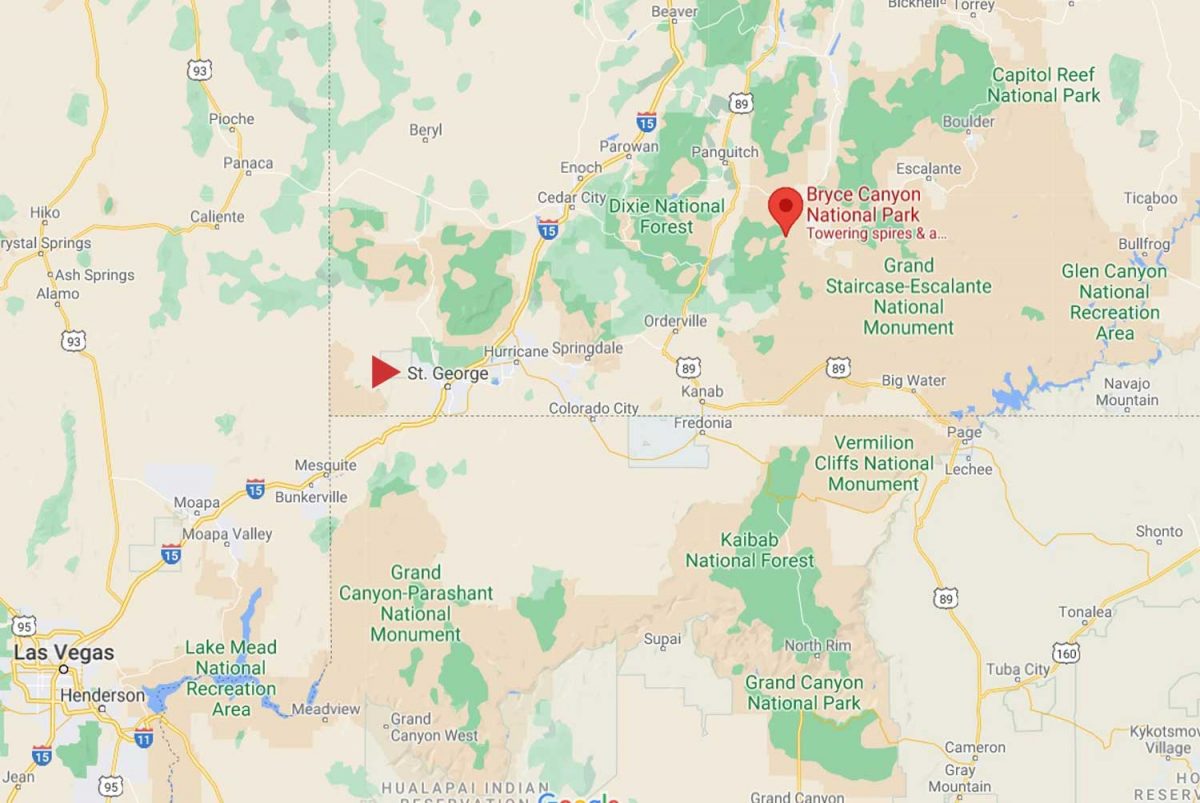

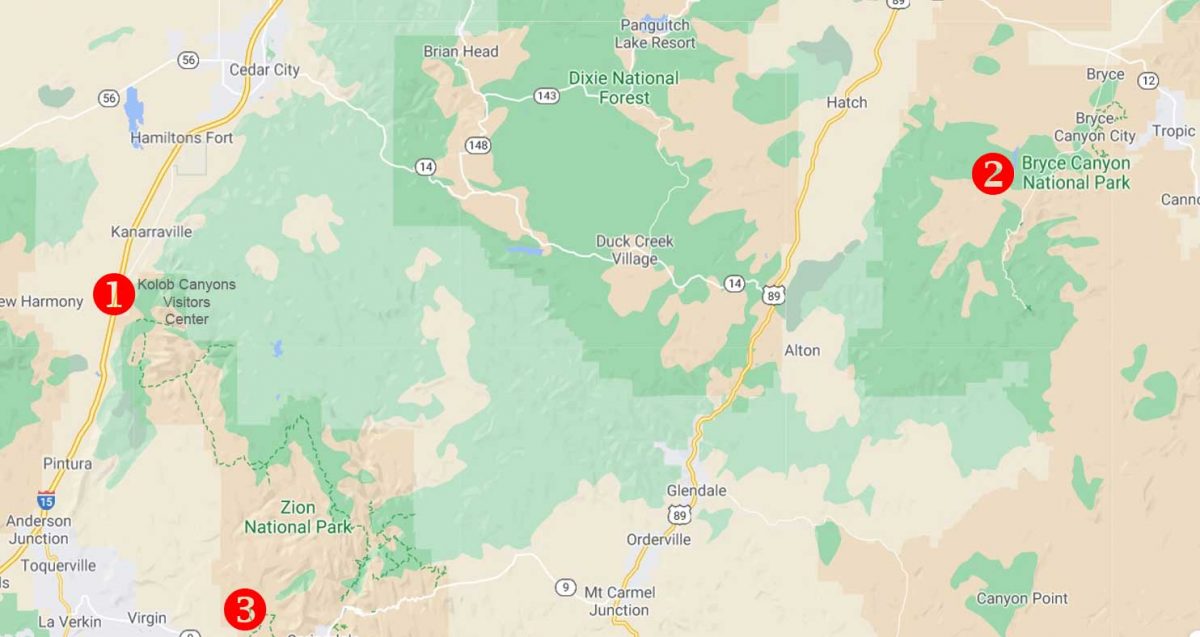

After finishing our breakfast at Ruby’s Inn the morning after our spectacular visit to Bryce Canyon National Park (my last blog), we headed southwest on Highway 89 to Zion National Park. I explained in my previous blog that we made a brief stop on the previous day’s journey from St. George, Utah to Bryce at the most westerly part of Zion, the Kolob Canyons Visitor’s Center, which is accessed from Highway 15. I’ve marked that with a #1 on the map below. Then we headed back on the highway to Bryce at #2. Our second day took us to Zion at #3, before heading back to St. George.

Kolob Canyons was interesting and gave us our first look at the Navajo Sandstone formation that comprises most of Zion. The sign says: This overlook reveals the cooler, more thickly forested world above the finger canyons. From this elevated viewpoint you can see the pattern of canyon-carving streams along cracks in the Colorado Plateau. Each finger canyon is like a miniature Zion Canyon showing similar erosion dynamics: broad at the mouth, it narrows to a deep slot in its upper reaches.

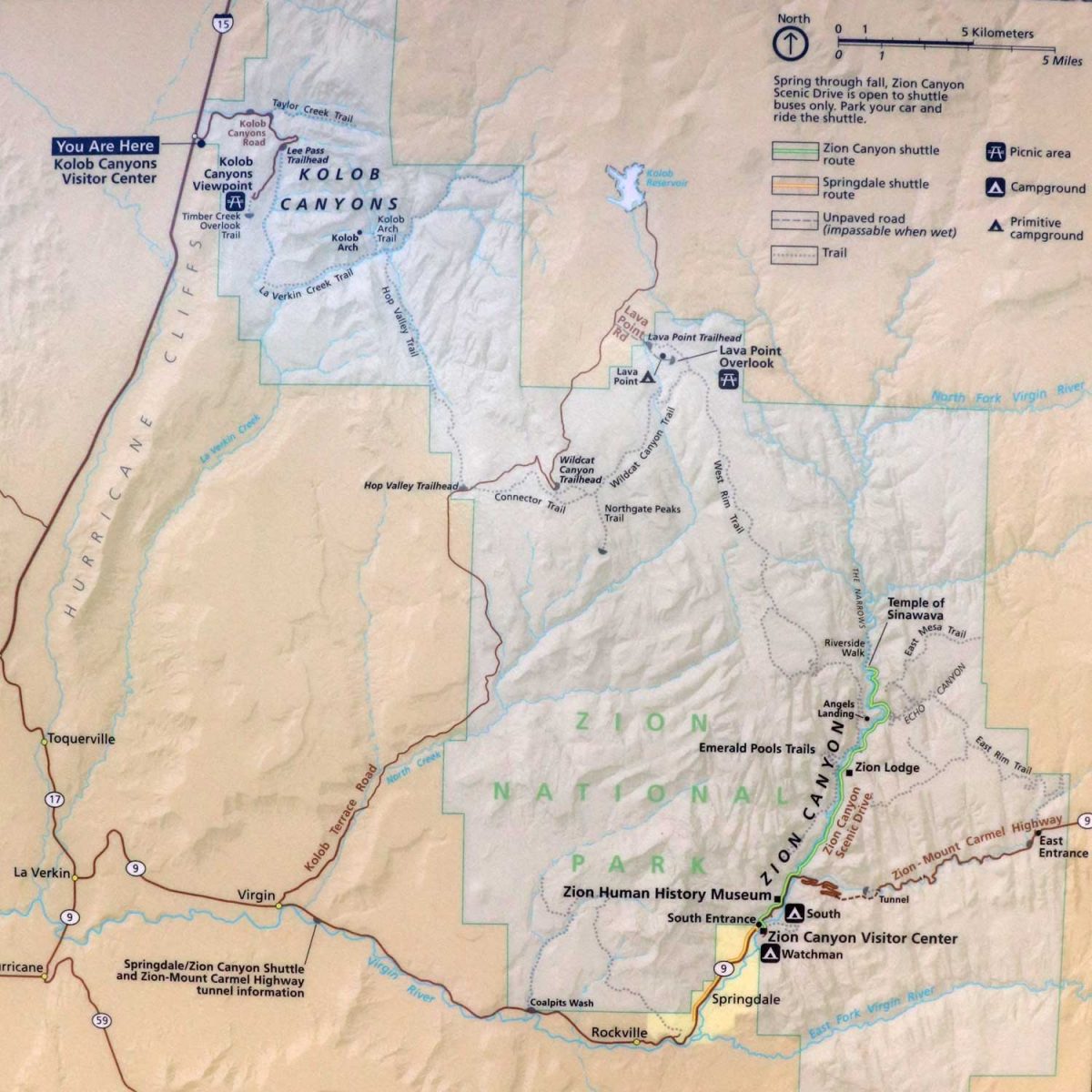

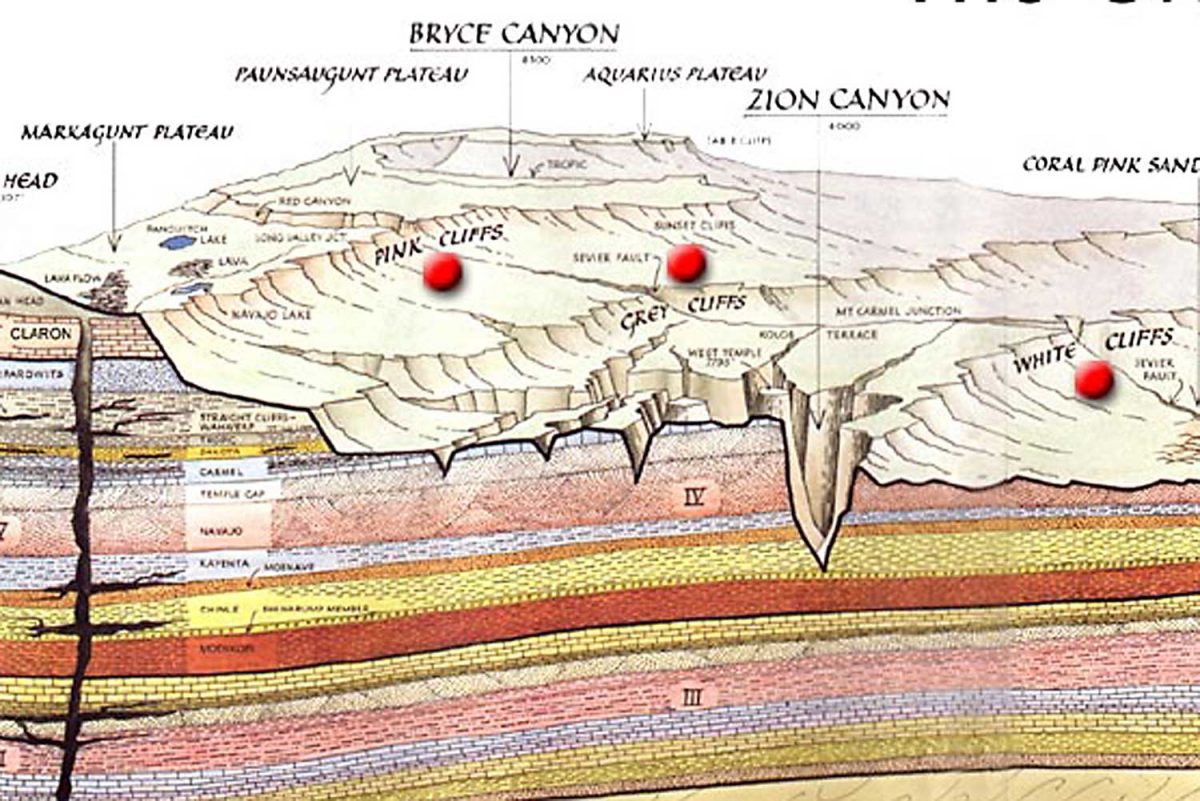

On the illustration below, you can see how widespread the two visitor areas of Zion are.

There were ponderosa pines in Kolob Canyon….

…. and Utah serviceberry (Amelanchier utahensis) was in full bloom on the 1st day of May.

But the main attraction on day #2 was the principal south entrance to Zion Canyon.

We walked across the pedestrian bridge into the park….

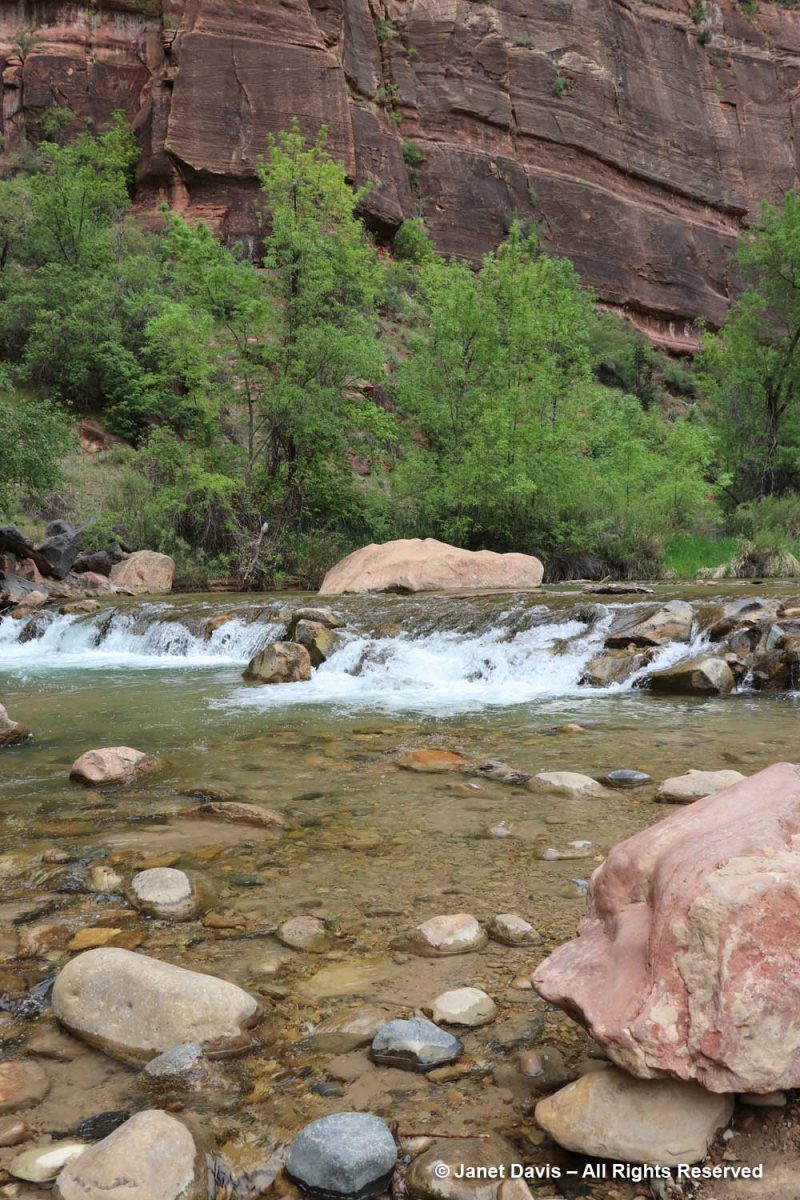

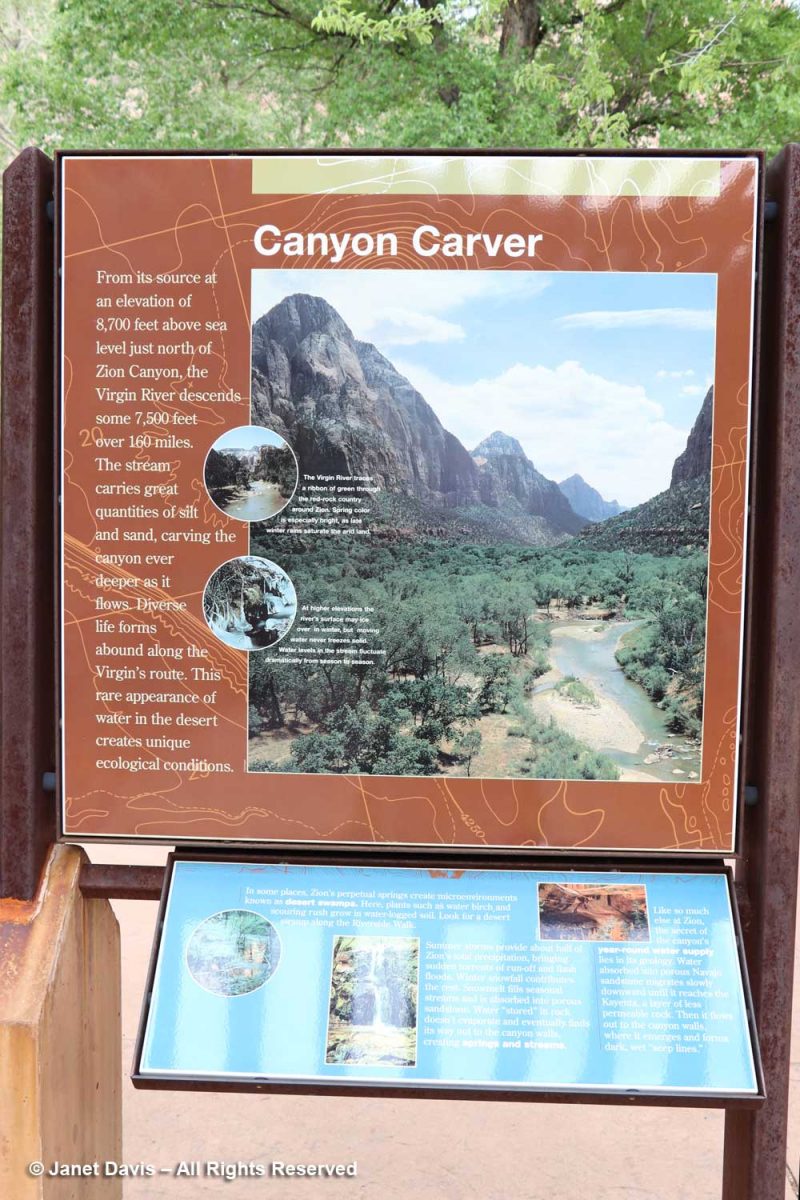

…. over the north fork of the Virgin River. It looks fairly tranquil below, but it has incredible power, especially in spring runoff, due to its steepness. In the 160 miles of its course, it drops 7,800 feet, i.e. 71 feet for every mile. That power has allowed it to carve the sandstone into canyons.

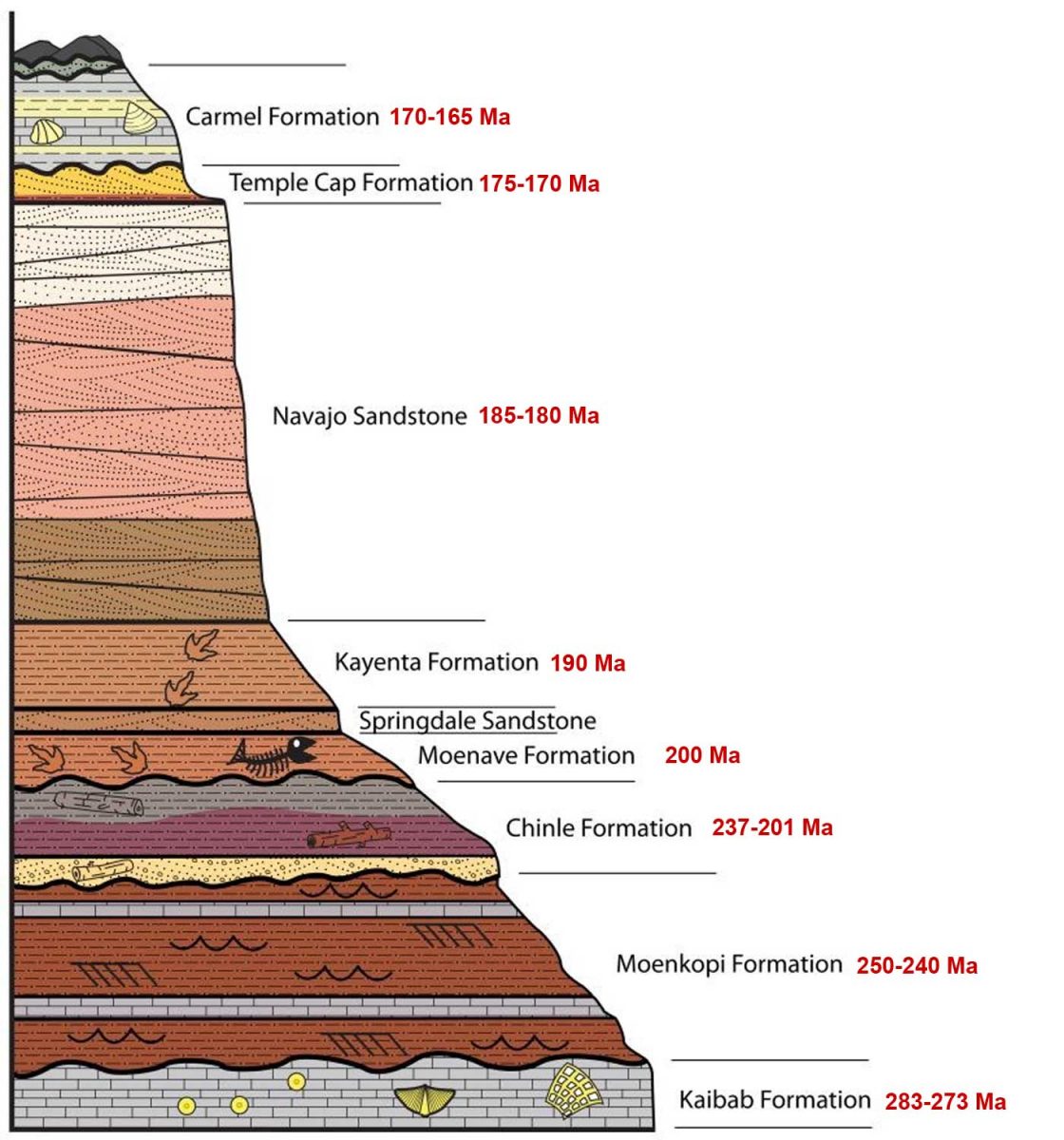

It’s tempting as you begin your walk or tram ride through Zion Canyon to look up at rugged peaks and think of them as mountains, but these are formations of early Jurassic (185-180 Ma) Navajo sandstone, in places 2,000 feet in depth, sculpted by erosion. Most were given names in the early 20th century; this one is the Watchman.

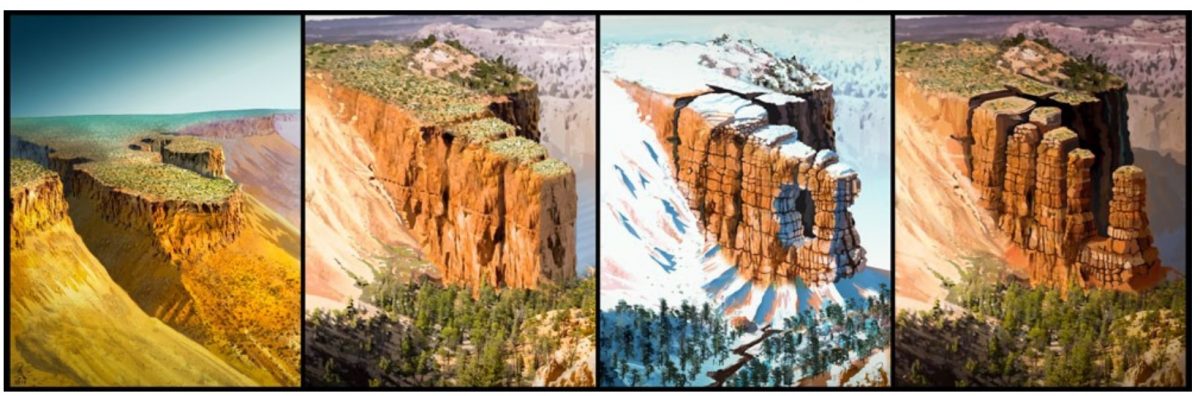

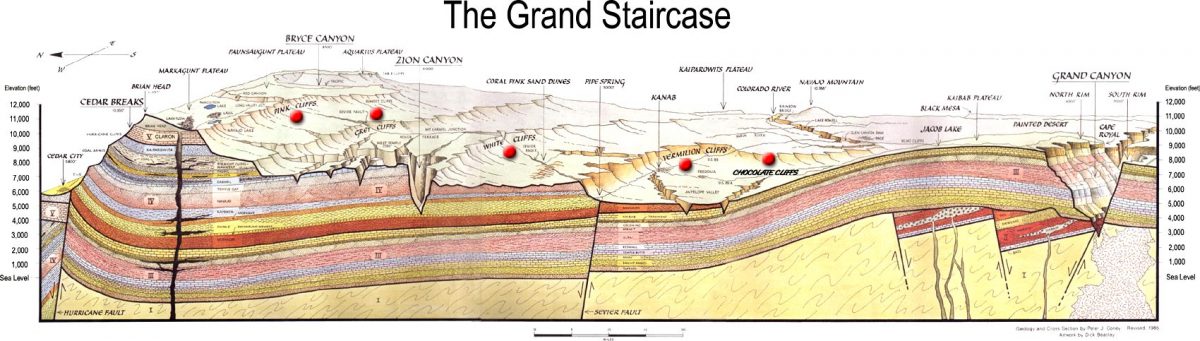

The graphic below, which I featured in my Bryce blog, shows the difference between the two parks. The Bryce amphitheatre with its thousands of hoodoos sits adjacent to the Paunsaugunt Plateau at around 8,300 feet, whereas Zion occupies a sandstone cleft in the earth surface.at 4,000 feet. I read that the youngest layer at Zion is the oldest layer at Bryce.

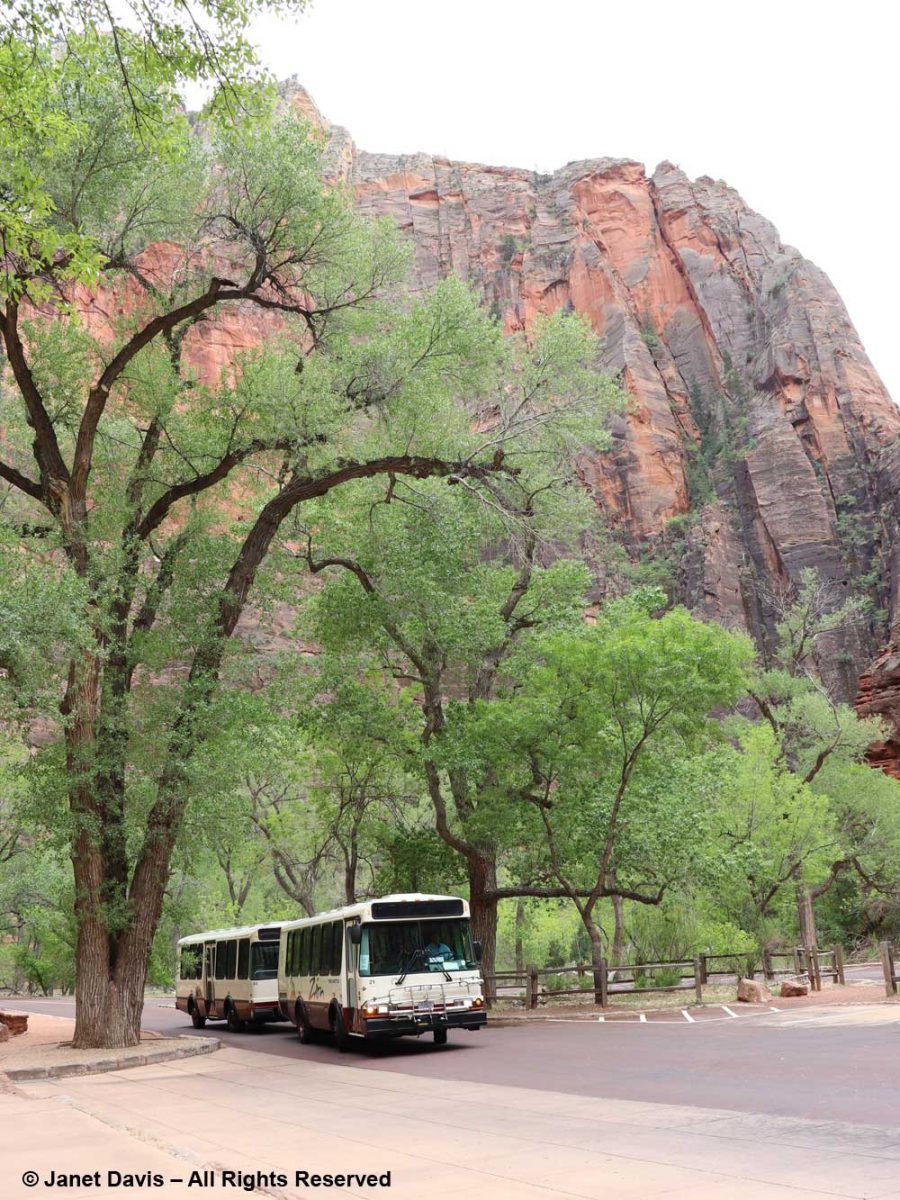

Because our time was fairly limited, we took a tram tour through the canyon. It passed various famous formations (and I’m thankful to Zion’s Brian Whitehead for helping me identify a few of them). The one at the top, below, is The Bee Hive, with The Sentinel at right, rear.

The colours of the Navajo sandstone are varied. representing millions of years of deposition of sand dunes from what was once the biggest desert in the world.

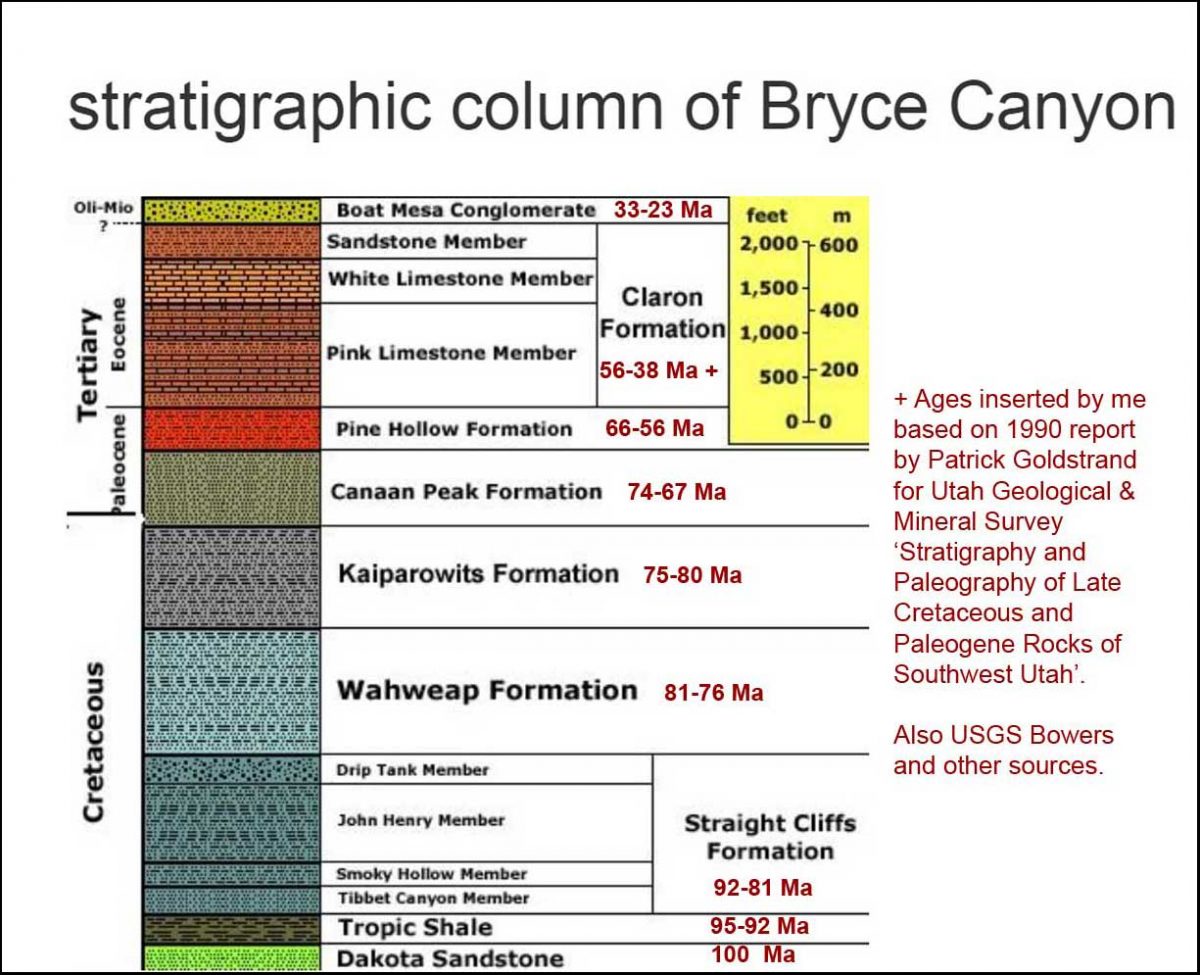

I’ve added ages to this NPS illustration, and you can see the variation in the colours of the large band of Navajo Sandstone. As the NPS says,“The range of colors of the Navajo Sandstone –red, brown, pink, salmon, gold, and even white—results from varying amounts and forms of iron oxide within the rock, and in the case of the white upper portion of the Navajo, the overall lack of iron. The processes behind the color variation are complex and took place in multiple phases over long periods of time. To start, the Navajo is made of grains of light-colored quartz sand, similar to those found in many modern dune or beach environments. Soon after being deposited in dunes, the sand grains were coated with a thin layer of reddish-brown iron oxide (the mineral hematite; a.k.a. rust). This was due to the chemical breakdown (oxidation) of very small amounts of iron-containing minerals within the sand, and made the earlier Navajo Sandstone a pinkish-red color overall.” (At the end of this blog, you’ll see a formation I passed outside Zion of the much older, therefore deeper, Moenkopi Formation.)

The tram took us past Mount Spry, with one of the Twin Brothers in the rear.

This was the view into Heaps Canyon ( the park’s famous slot canyons) with the Emerald Pools beyond. Reading about it, the phrase “hanging rappel” is a good sign that I wouldn’t have had this one on my to-do list.

I used my telephoto lens to photograph the top of Castle Dome, which you can see in the previous photo. The white layer of sandstone reflects the deficit of iron in the rock, while the orange layer clearly illustrates the cross-bedding of the windswept dune formations.

The canyon was filled with Frémont’s cottonwood (Populus fremontii), native to riparian areas throughout the southwest.

Angels Landing is a narrow, 1,488-foot tall (454 m) formation in Zion with a chain-handhold-assisted hiking trail that was cut into the sandstone in 1926. In the past 20 years, 13 hikers have fallen to their deaths from Angel’s Landing.

With my telephoto lens, I could see beyond the Angel’s Landing trail up to the broad white expanse of Cathedral Mountain.

These formations across the Virgin River are called The Pulpit. Located in the Temple of Sinawava, they represent the end….

….. of the tram ride in the canyon.

From there, it was all about the Virgin River, including its treed banks….

…. and its changes of elevation….

,,,, to understand its role in creating the canyon that comprises Zion National Park.

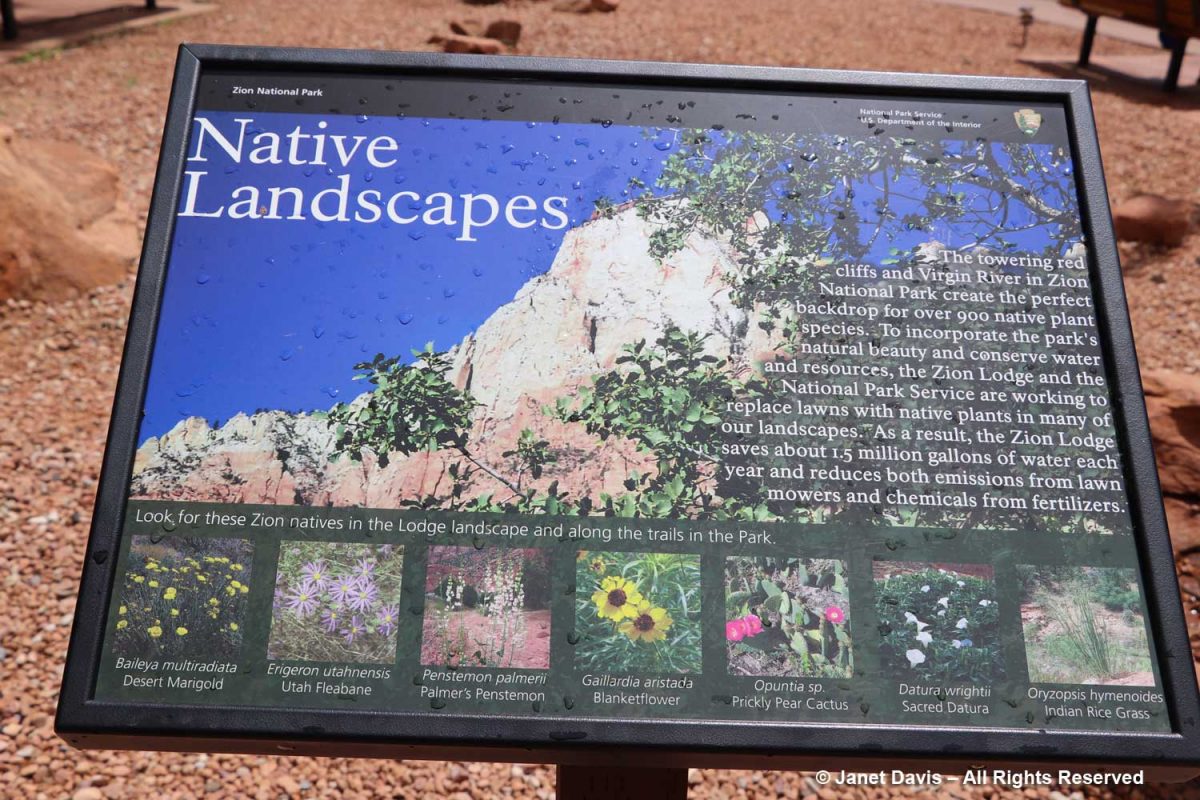

But I was interested to see all the native plants I knew that grow here – over 900 in total.

The Zion Narrows Riverside Walk Trail, aka the Gateway to the Narrows, hugs the canyon wall and allows visitors to feel the immense scale of the rock faces.

There were lovely little pools adjacent to the river…..

…. and I’m showing the portrait view here to include the vertical stripes called ‘desert varnish’. These striations are coatings on the outside of the rock face featuring bacteria-oxidized minerals from the atmosphere, mostly manganese (Mn), causing black stripes, and iron (Fe), causing shades of reddish-brown. These shiny coatings take thousands of years to form, so the rock walls featuring them are generally very stable and not easily eroded. Native Indians, including the Southern Paiutes who inhabited Zion – which they called Mukuntuweap – prior to the 1800s, used the rock faces with desert varnish as the canvases for their rock paintings or petroglyphs.

I was delighted to stand under the ‘hanging gardens’ of Zion.

Nearer the river, there were plants tucked in among river rocks, such as shooting star (Primula pulchellum, formerly Dodecatheon)….

….. with its lovely dark throat….

…. and western columbine (Aquilegia formosa).

The wetlands adjacent to the Virgin River contain many interesting plants, including watercress (Nasturtium officinale), a non-native that thrives in running water.

Visitors might be puzzled to see prickly-pear cacti (Opuntia spp.) along the river, but for much of the year, Zion has a desert climate.

It was time to say farewell to Zion, and as we headed back down the trail, I spotted a tiny canyon wren (Catherpes mexicanus). Wildlife! I was happy to have checked off a little symbol of the rich animal diversity found in the park.

It was a good time to have a photo of my husband Doug, left, and his kindergarten classmate Peter, right (with me in the middle). For many years, they were also business partners. Without Peter and his wife Lynne, who now live in St. George, we would not have had this wonderful opportunity to visit Bryce Canyon and Zion National Park.

While driving out of Zion past the town of Springdale on our way back to St. George, we passed an amazing multi-layered rock formation, which I snapped with my cellphone, before….

…. deciding to use my zoom lens to see it better. This is the Moenkopi formation, which appears near the bottom of the stratigraphic illustration I showed earlier in this blog. Its age is 250-240 Ma, or 70 million years older than the Navajo sandstone in Zion. Eager to discover a little more, I found a reference to it on the website of retired Colorado geologist Dr. Mike Nelson. He graciously answered my query: “You are looking at the Moenkopi with the Shinarump Member, the lower unit of the Chinle. The brick red bedded mudstone and siltstone prominent in the closeup represents tidal flat and coastal plain deposition. It is known as the lower red member (informal) of the Moenkopi. Below that is probably the shallow marine Timpoweap Member. Above the lower red member is the Virgin Limestone Member, the middle red member, the Shnakaib Membern and the upper red member. The formally named members represent transgressive shallow marine waters and are followed by regressive non marine rocks. During the Triassic the coastal area was a very gentle slope so the shoreline could fluctuate many miles with only a few feet of rise in sea level. There is a substantial amount of missing geological time (an unconformity, Tr3 in the geological jargon) between the Moenkopi and the Chinle.”

I might not be a geologist, but what a wonderful world we live in, where these secrets in rocks hundreds of millions of years old can be revealed so readily in a photo of a formation by the side of the road.

*******

If you enjoy reading about geology (from an amateur), you might like my blogs on

* Oregon’s Thomas Condon Paleontology Center

* My Jaded Past, My Rocky Present (a personal memoir)