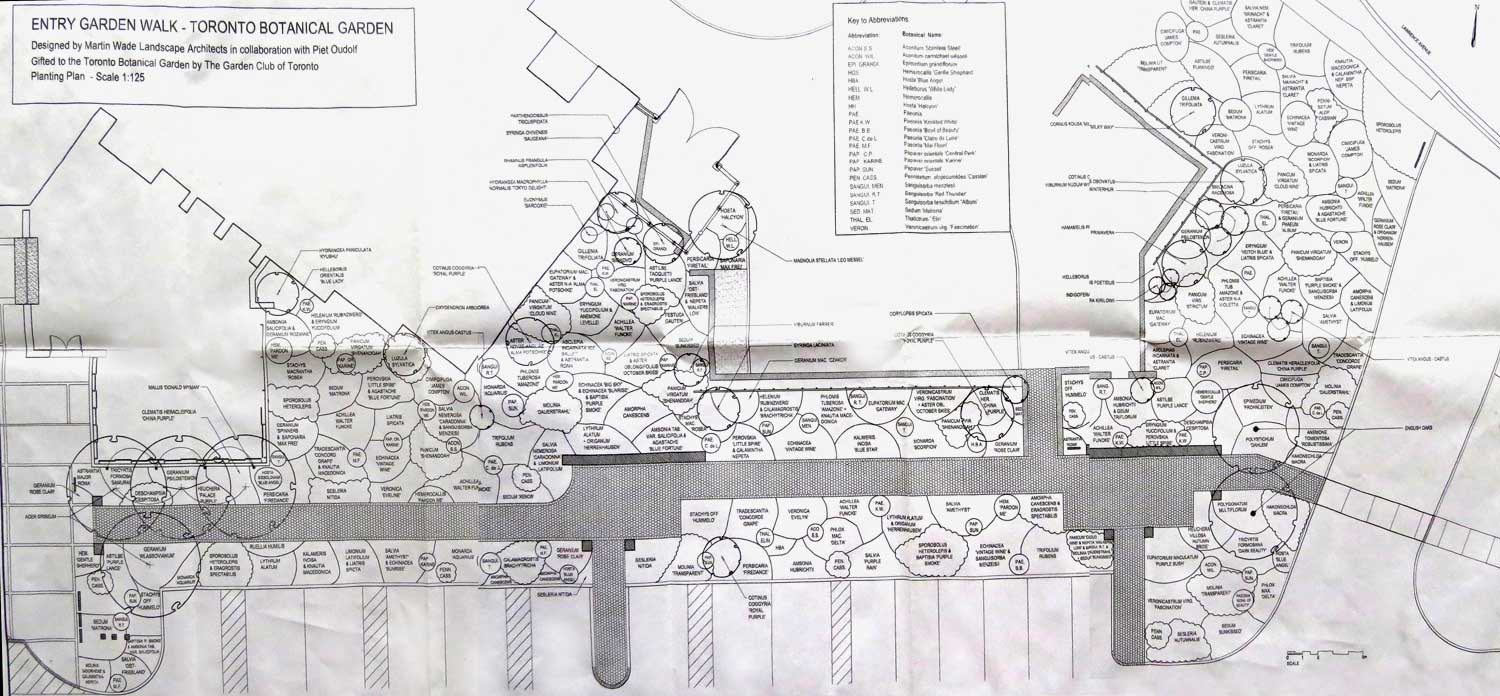

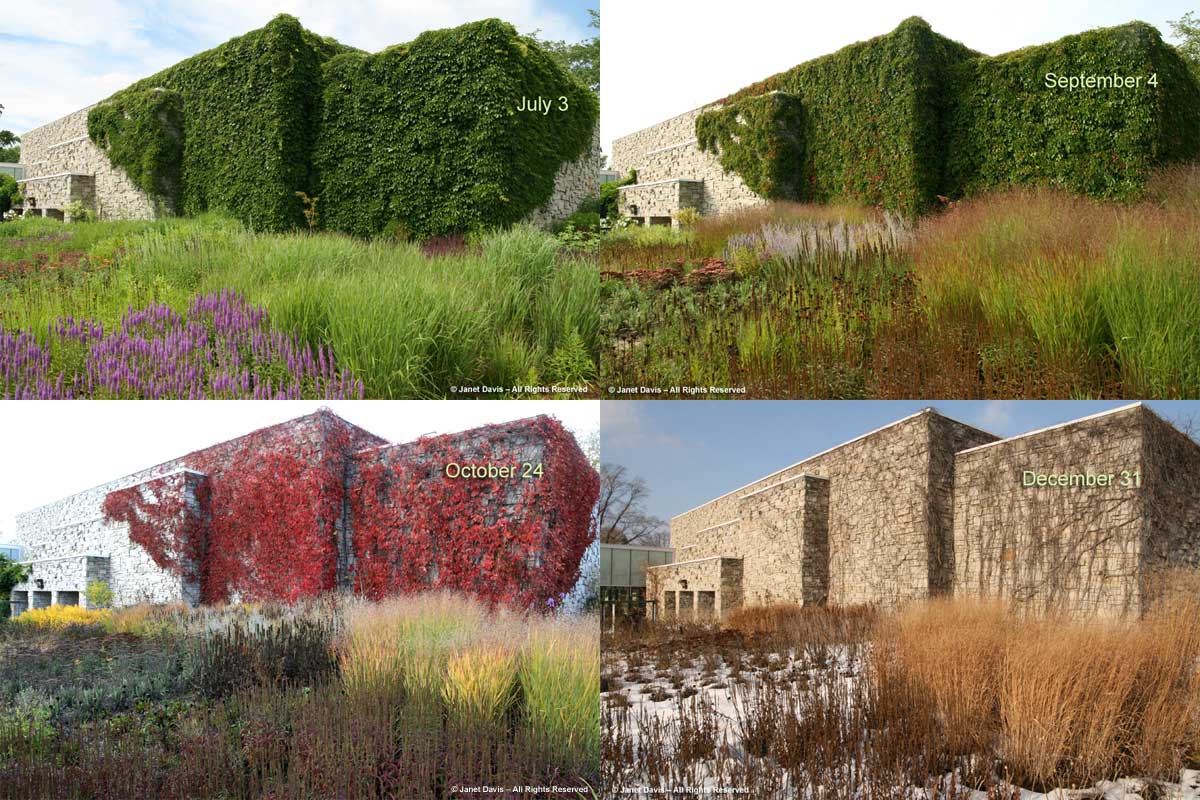

Following on part one, this is the second part of my exploration of the Piet Oudolf-designed entry border at the Toronto Botanical Garden.

The plant design of the entry walk garden at Toronto Botanical Garden is much more exacting than the drifts and blocks in a conventional border. If you think of a broad meadow like this as a painting, the effect of each series of neighbouring brush strokes is known in advance. For these plants are like children to Piet Oudolf, many grown and observed for decades in his own Dutch garden, many even bred by him or fellow nurserymen in the Netherlands and Germany.

Designed Combinations

Let’s skip around Piet’s original planting design and have a look at twelve of the combinations he planned, as they manifested themselves over the past decade. It’s important to note that all these plants fulfill Piet’s mandate that plants must be: relatively adaptable to soil, i.e. neither too wet nor too dry; vigorous enough to grow without fertilizers or pesticides; strong enough to stand without staking (as with the lovely single peonies in Part One, in contrast to floppy double peonies). Plants should be resilient and long-lived. His plant combinations are not dictated by colour, but by form; however, you’ll see some lovely colour pairings in the examples below.

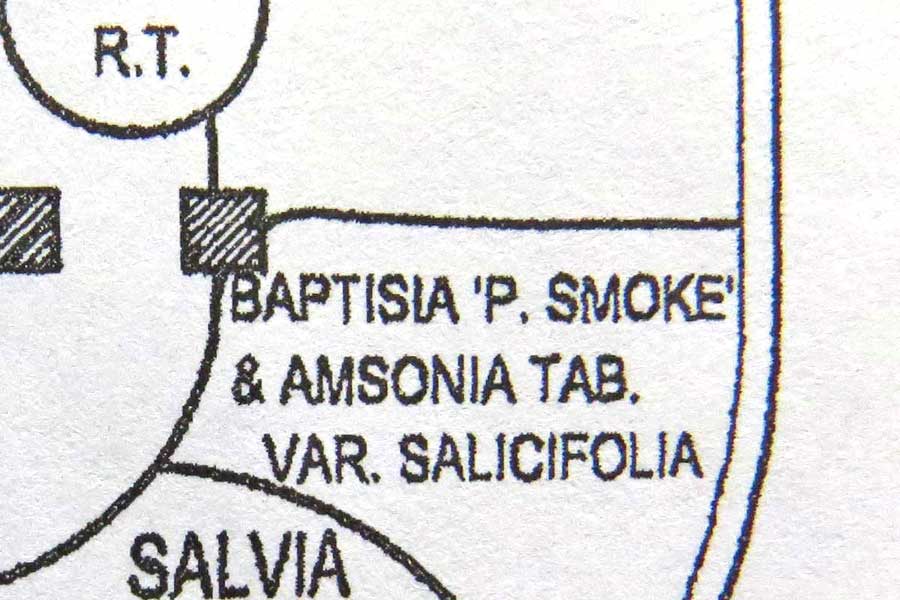

1.Willowleaf bluestar (Amsonia tabernaemontana var. salicifolia) and ‘Purple Smoke’ false indigo (Baptisia australis).

This is one of the most stable and effective pairings in the entry garden.

Year after year, these two North American natives (technically, the baptisia selection is called a “nativar”, i.e. native cultivar) emerge and come into flower at exactly the same time. They seem to be on the very same wavelength, and equally lovely. And the amsonia, of course, takes on golden-yellow hues in autumn.

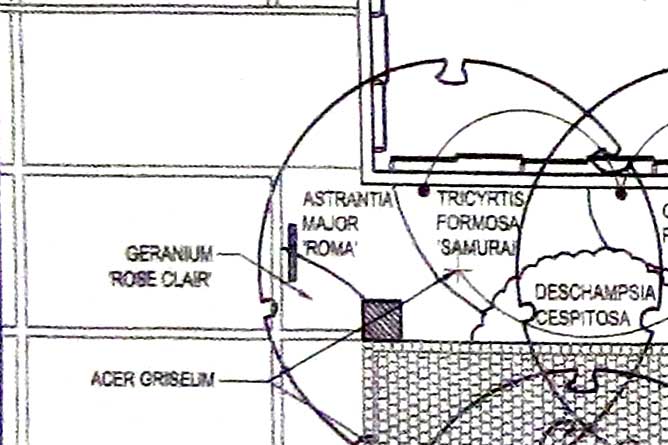

2. ‘Roma’ masterwort (Astrantia major) and ‘Rose Clair’ geranium (G. x oxonianum).

These two late-spring perennials share a pleasing rosy hue and a soft presence.

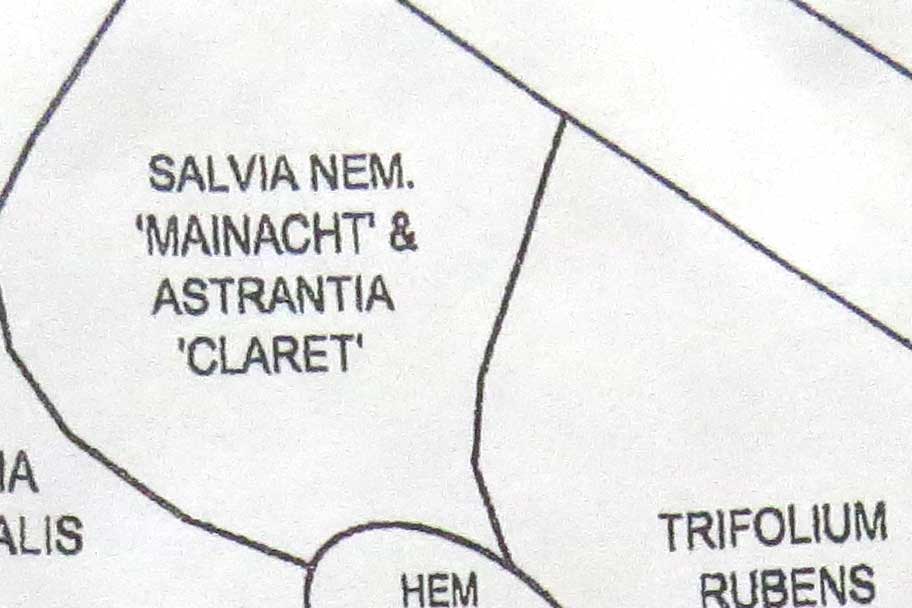

3.‘Claret’ masterwort (Astrantia major) & ‘Mainacht’ =’May Night’ meadow sage (Salvia nemorosa).

Dark-red ‘Claret’ astrantia is another Piet Oudolf breeding selection, a seedling (like his ‘Roma’ above), of ‘Ruby Wedding’. It looks lovely here in a romantic June combination with indigo-blue ‘Mainacht’ sage. To the left is ornamental clover (Trifolium rubens), to the right is drumstick allium (A. sphaerocephalon).

4. Alaskan burnet (Sanguisorba menziesii) & ‘Amethyst’ meadow sage (Salvia nemorosa).

I’ll talk a little more about the wonderful burnets in Special Plants below, but this is a good early-summer combination: with zingy, dark-red Alaskan burnet (Sanguisorba menzisii) at rear, violet-mauve Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’ in front, and a lttle spiderwort (Trandescantia) too. If you’re a bee-lover, the meadow sages are fabulous lures.

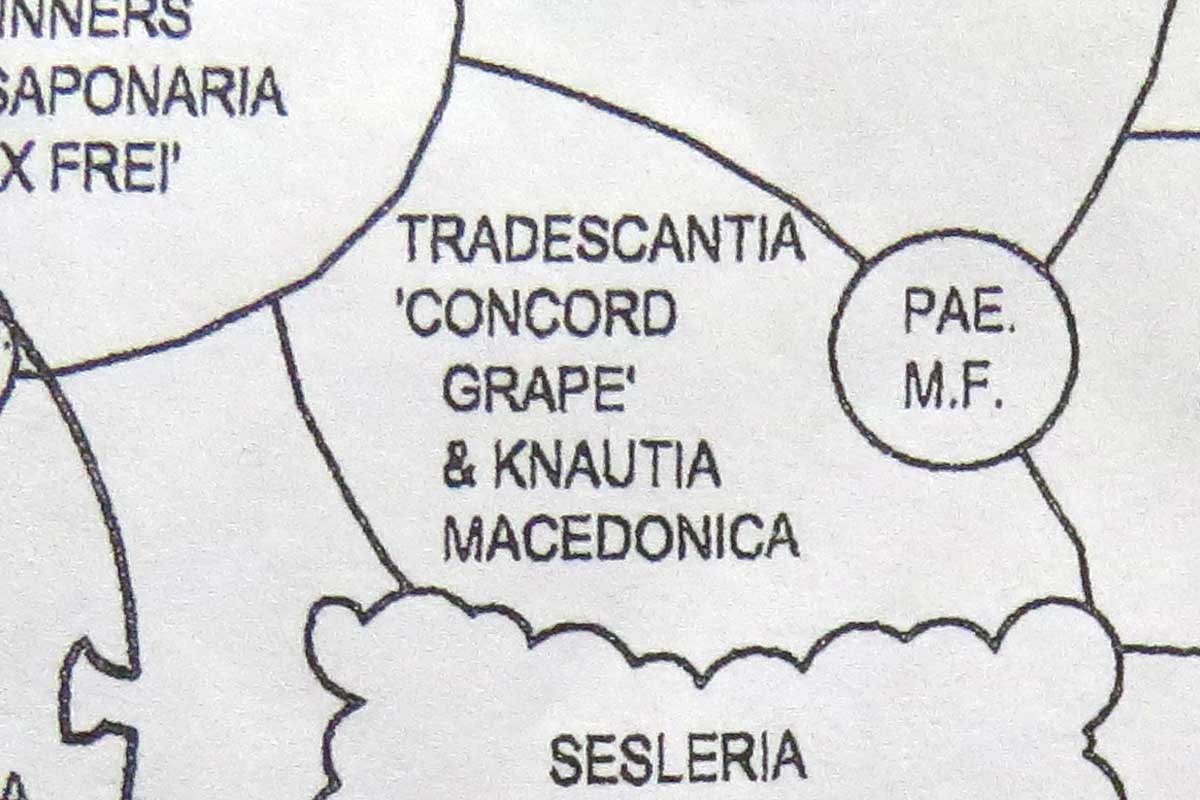

5. ‘Concord Grape’ spiderwort (Tradescantia x andersoniana) & Knautia macedonica.

Speaking of bees, both violet-purple spiderwort and dark-red knautia are excellent bee plants, but I do love these jewel-box colours together in early summer. The light-purple cranesbill is Geranium ‘Spinners’.

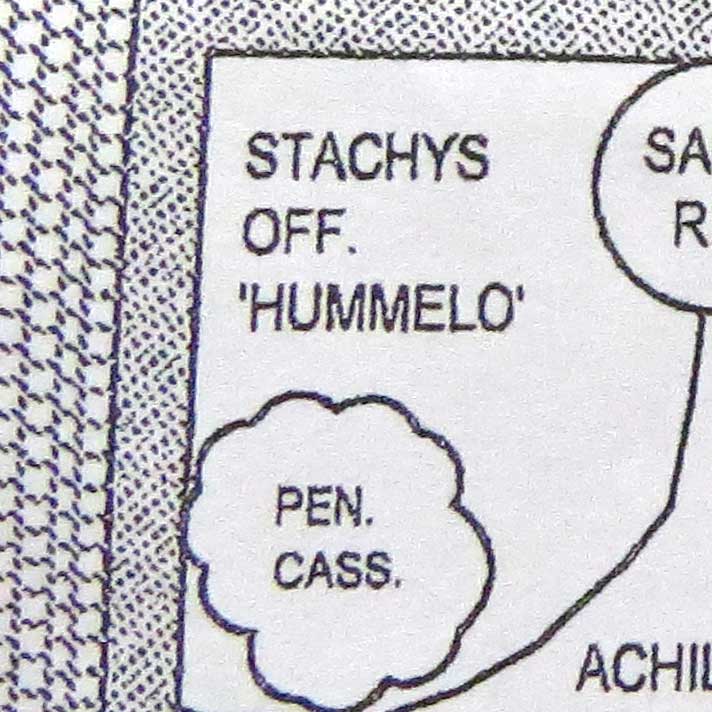

6. ‘Hummelo’ betony (Stachys officinalis) & ‘Cassian’ fountain grass (Pennisetum alopecuroides).

Here are two of Piet’s German heritage plants growing side by side: Ernst Pagel’s lovely Stachys officinalis ‘Hummelo’ and the fountain grass named for Cassian Schmidt, director of Hermannshof.

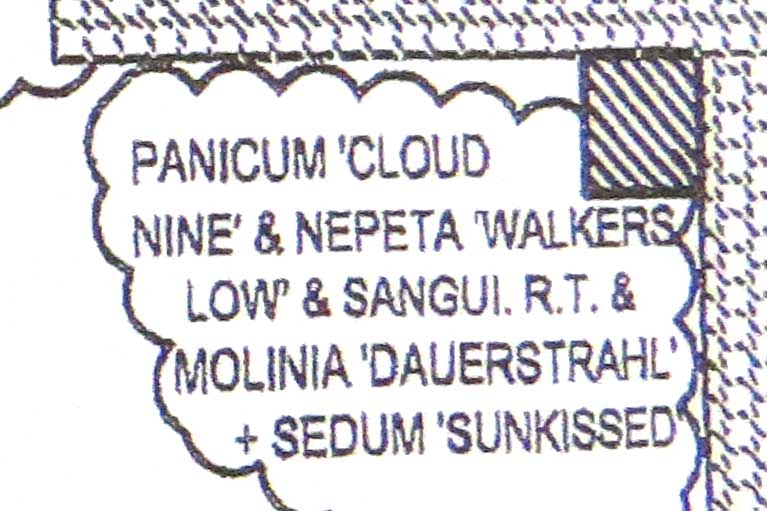

7. ‘Walker’s Low’ catmint (Nepeta racemosa) & ‘Cloud Nine’ switch grass (Panicum virgatum)

Catmints are workhorses: long-flowering, great for bees, hardy, with tidy, aromatic foliage. They do get big in time, but that just means more plants after dividing. Here it is as the switch grass (a warm season grass) is just getting going in early summer. It’s called ‘Cloud Nine’ for its impressive height, to 7 feet (2.1 metre).

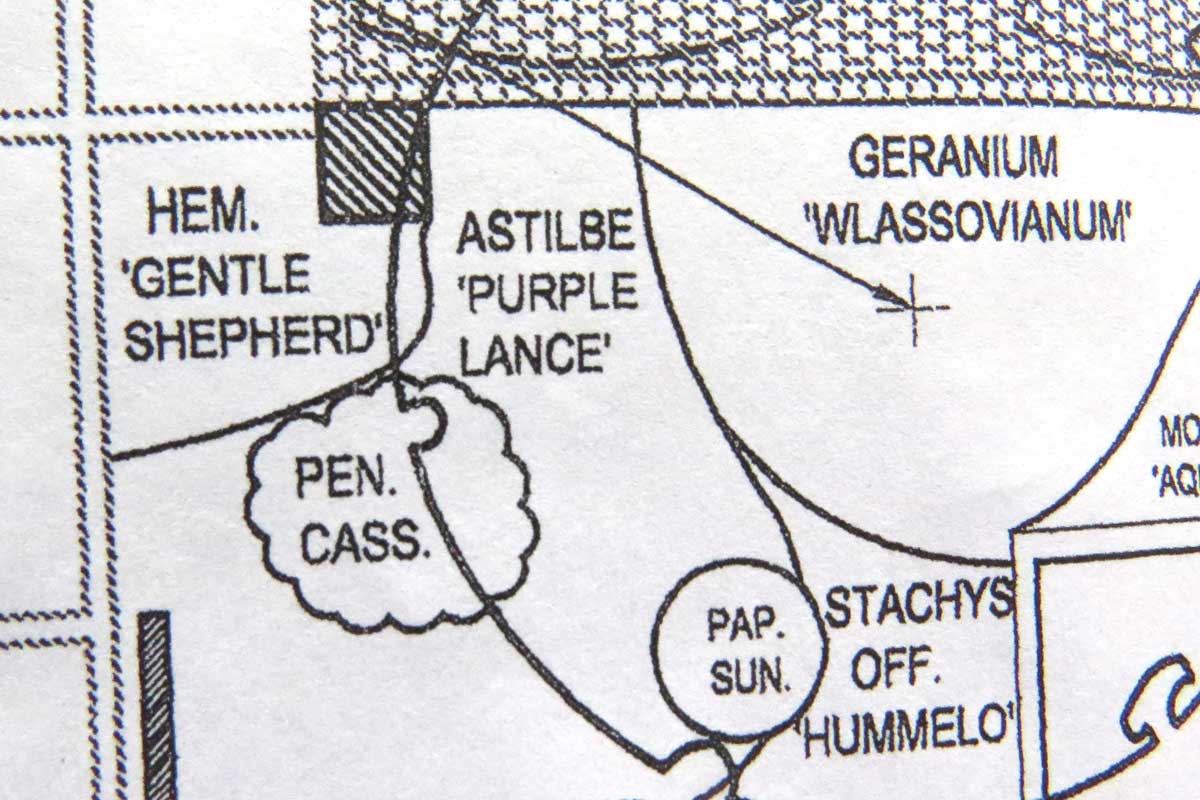

8. ‘Gentle Shepherd’ daylily (Hemerocallis) & ‘Purpurlanze’=’Purple Lance’ astilbe (A. chinensis var. tacquetii)

When the entry walk garden first came into bloom in 2008, I was surprised to see a few daylilies in it. I suppose I thought that with Piet’s focus on the importance of good foliage, daylilies would simply not make the cut, given the tendency of their leaves to go brown and look straggly in late summer. But surprise! There are a few old-fashioned daylilies, including pale-yellow ‘Gentle Shepherd’ which makes a good companion to the fuchsia-pink flowers of spectacular ‘Purpurlanze’ astilbe and is considered a seasonal “filler” plant (see Scatter Plants and Fillers below), with other perennials emerging to carry on the late summer show.

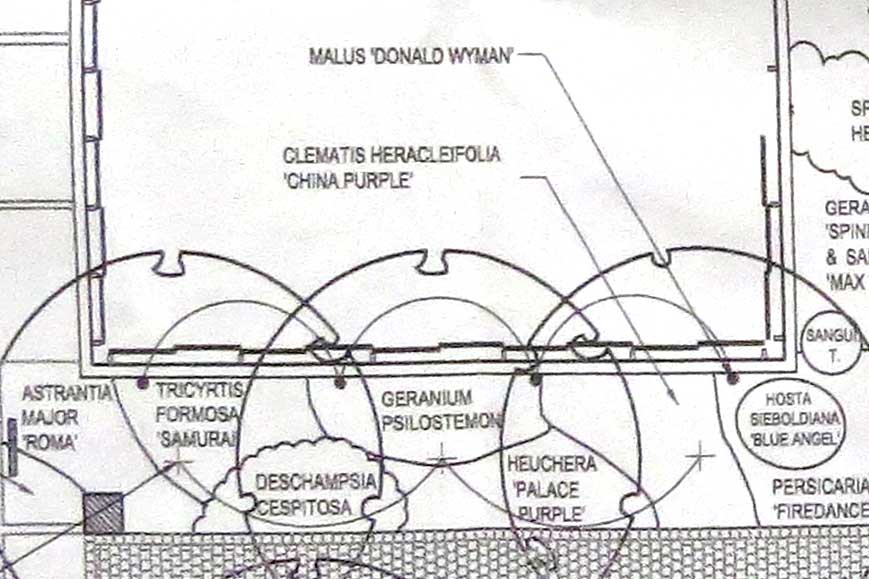

9. ‘Blue Angel’ hosta (Hosta sieboldiana) & ‘Firedance’ mountain fleece (Persicaria amplexicaulis).

Yes, Piet Oudolf uses hostas! (Shhh…don’t tell anyone….) Actually, the big ‘Blue Angel’ hostas here are favourites of Piet’s for their beautiful leaf texture. They act as anchors (there’s one at the other end, too) for this long border. And when they’re flowering, there are always bees buzzing around the white blooms. I like the way the tall white burnet behind echoes the hosta flowers. These hostas also undergo their own foliage transformation, turning gold in autumn. The ‘Firedance’ mountain fleece or bistort (Piet’s introduction) is more compact than ‘Firetail’, and a good, long-flowering perennial.

A honey bee works the flowers of Hosta sieboldiana ‘Blue Angel’.

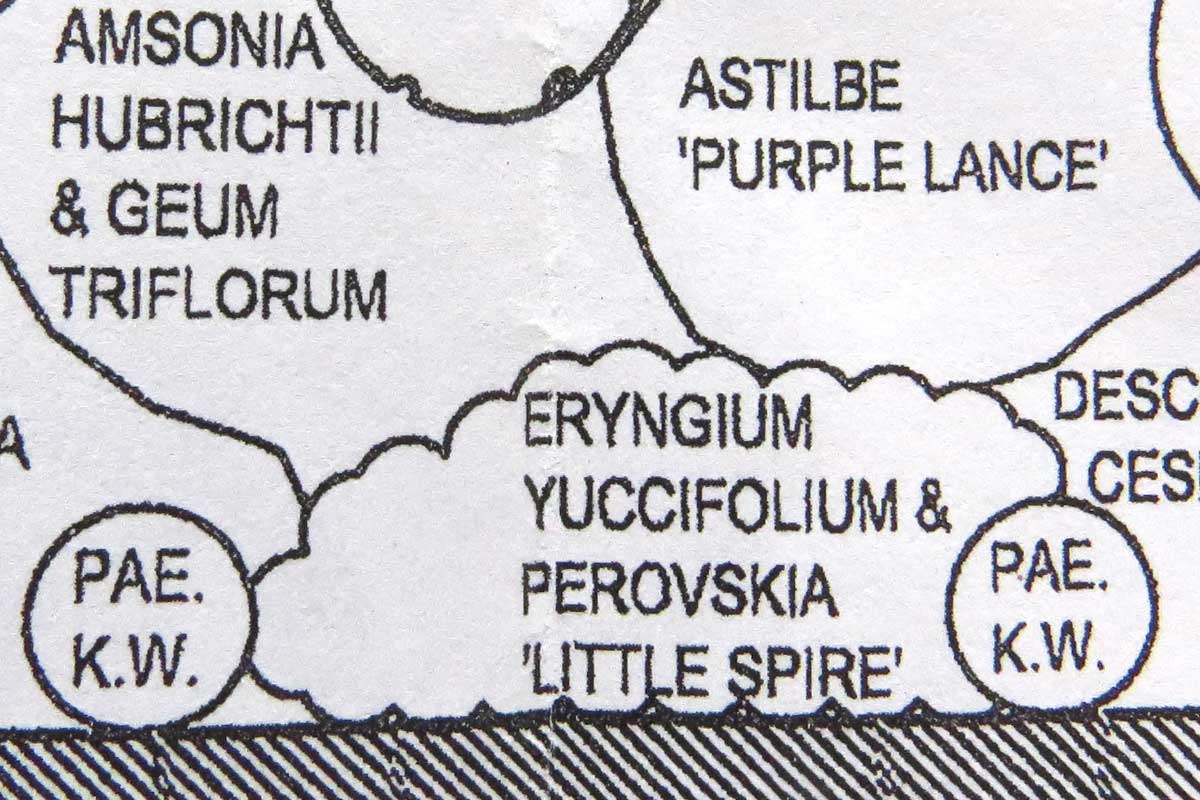

10. ‘Little Spire’ Russian sage (Perovskia atriplicifolia) & rattlesnake master (Eryngium yuccifolium)

This is one of my favourite combinations in the entire entry border: the yin-yang combination of the assertive, spiky rattlesnake master and the soft, hazy spires of Russian sage. Peeking through behind are more pink ‘Purpurlanze’ astilbe and ‘Gentle Shepherd’ daylilies.

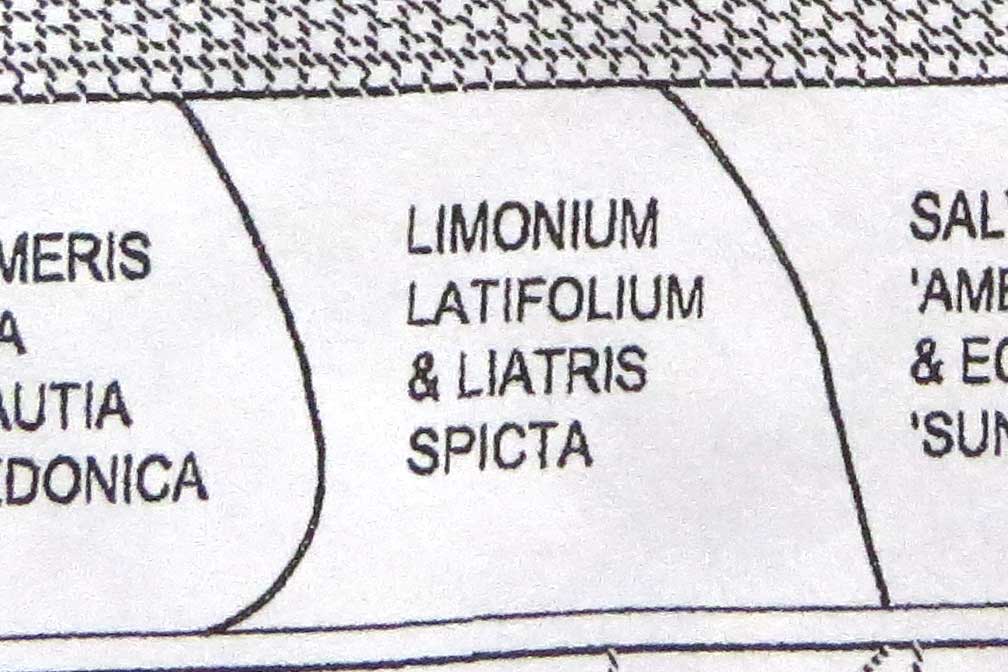

11. Sea lavender (Limonium latifolium) and dense blazing star (Liatris spicata)

In writing in Hummelo: A Journey Through a Plantsman’s Life about their collaboration on the 1999 book Designing with Plants, Noel Kingsbury refers to a section of the earlier book called Moods. “We outlined the impact of the more subtle and hard-to-pin-down aspects of planting design, such as the play of light, movement, harmony, control and ‘mysticism’. I am still not 100 percent sure I know what we meant by this category, apart from a lot of mist in the pictures, but it looked good and sounded good.” For me, the vignette below touches a little on mysticism. There’s something about this combination of forms — the solid echinaceas, the constellation of spent knautia seedheads, the regimental spikes of blazing star, the soft cloud of sea lavender, the blades of grass — that seems almost dream-like. This is my childhood meadow idealized.

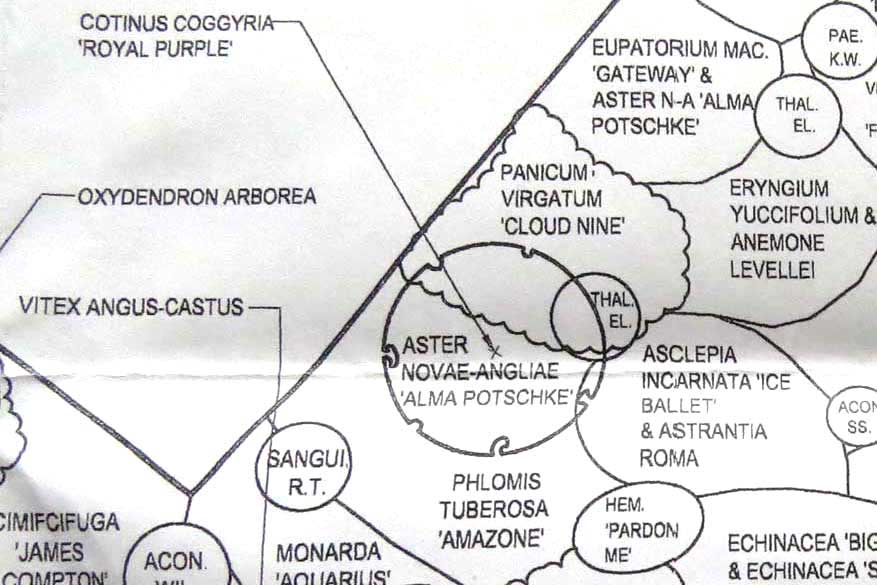

12. ‘Royal Purple’ smokebush (Cotinus coggygria) & ‘Amazone’ Jerusalem sage (Phlomis tuberosa)

Once in a while, you might see a story (usually British) that refers to Piet Oudolf and the other practitioners of the so-called “Dutch Wave” of naturalistic design as focusing entirely on perennials to the exclusion of woody shrubs and trees. If you don’t know Piet’s work with trees and shrubs (including roses) at The High Line and elsewhere, you won’t see the fallacy in that line of thought. Though the entry garden at the TBG is primarily a perennial meadow, there are shrubs and vines in a few places, including lilac (Syringa), Kousa dogwood (Cornus kousa), witch hazel (Hamamelis x intermedia), chaste-tree (Vitex agnus-castus) and purple-leaved smoke bush (Cotinus coggygria ‘Royal Purple’). I love the vignette, below, with the burgundy-red foliage and smoky fruit of the smoke bush and the Phlomis tuberosa ‘Amazone’ with the tall alliums (likely ‘Gladiator’) and a sprinkle of white foxglove penstemon (P. digitalis), which is not on Piet’s plan but is now in the border and quite lovely in early summer.

Scatter Plants and Fillers

In the book Hummelo: A Journey Through a Plantsman’s Life, by Piet Oudolf and Noel Kingsbury (The Monacelli Press, 2015), there are pages devoted to Piet’s use of “scatter plants” and “fillers”. Scatter plants are defined as “individuals or very small groupings of plants interspersed among blocks of plant varieties or through a matrix planting, breaking up the regularity of the pattern; their distribution is generally quasi-random.” Scatter plants can act as links in a border, even unifying it, adding contrasting splashes of colour, like the orange-red Helenium autumnale ‘Rubinzwerg’, below…..

…or a pop of colour that later disappears, like the Oriental poppies in the entry garden that later go dormant.

Fillers are plants whose interest lasts less than three months; though they may have good foliage, they don’t have the structure normally associated with an Oudolf design. They’re good for “filling gaps earlier in the year.” Knautia macedonica does this and cranesbills or perennial geraniums do, too. As Piet Oudolf and Noel Kingsbury wrote in Designing with Plants (Timber Press, 1999), “Think how quickly the neat hemispheres of a hardy geranium turn into a sprawling mass of collapsed stems once the flowers have died.” Yet, when in bloom, they give a starry effect, like the white form of mourning widow cranesbill (Geranium phaeum ‘Album’), below, twinkling among the opening blossoms of Paeonia ‘Bowl of Beauty’.

Grasses

If there’s a hallmark group of plants that defines a Piet Oudolf design, it is ornamental grasses. In fact, he and Anja believed so strongly in their value in gardens that they held an annual Grass Days at their garden in Hummelo. And the 1998 book Gardening with Grasses, co-written by Michael King and Piet Oudolf, advanced that respect. Among the grasses featured in the entry garden are:

1.‘Skyracer’ moor grass (Molinia arundinacea), shown here with ‘Gateway’ Joe Pye Weed (Eutrochium maculatum). This grass is the perfect example of Piet’s use of plants that act as “screens and curtains”. In Designing with Plants, they’re described as “mostly air, and their loose growth creates another perspective as you look through them to the plants growing behind.” This rosy pairing, incidentally, also says ‘mysticism’ to me.

2.‘Cassian’ fountain grass (Pennisetum alopecuroides), here with ‘FIretail’ red bistort (Persicaria amplexicaulis)

3. Korean feather grass (Calamagrostis brachytricha). Lovely and hardy as it is, its plumes gorgeous in late summer and autumn, this grass did exhibit a tendency to seed around in the entry garden at TBG and had to be watched carefully.

Here is Korean feather grass in winter.

4.Tufted hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa) with sea lavender (Limonium latifolium)

5.’Shenandoah’, a selection of the tallgrass prairie native switch grass (Panicum virgatum), here showing its reddish leaves.

6.‘Strictum’ switch grass (Panicum virgatum) with its gold fall colour and seedheads of penstemon and echinacea.

7. Northern dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis), another tallgrass prairie native, its tiny, zingy flowers doing a dance with the small, pale-pink blossoms of North American native winged loosestrife (Lythrum alatum). More on this perennial in the next section.

Native North American Plants

Mention of the little-known native winged loosestrife brings me to Piet Oudolf’s use of native North American plants. By the time he was commissioned to do the planting scheme for the TBG’s entry border in 2005-6, Piet had become friends with Wisconsin plantsman Roy Diblik, author of The Know Maintenance Perennial Garden, with whom he worked on Chicago’s Lurie Garden at Millennium Park. As we learn in Hummelo: A Journey Through a Plantsman’s Life, when they visited the Schulenberg Prairie together in 2002, Roy recalls that Piet “was so taken with it. It was a very emotional moment for him.” After visiting this prairie and the Markham prairie later that year, Piet began to use many more North American plants in his designs, including some of the less well-known species in my list below.

1.Winged loosestrife (Lythrum alatum) – Mention ‘purple loosestrife’ to ecologically-aware people and alarm bells ring. Try telling them that there IS a native purple(ish) loosestrife and they don’t trust you. Or it could mutate. Or it might really be that other one, the Eurasian invader that’s drying up wetlands everywhere (Lythrum salicaria). But part of Piet Oudolf’s education with Roy Diblik was the discovery of this sweet plant. Native to moist prairies in Illinois and other parts of the northeast, it is at home in a well-irrigated garden where, rather than taking over like its cousin, it will work hard just to have its little pink flowers noticed.

Here’s winged loosestrife with ‘Ice Ballet’ swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata). Both species are wetlanders, but do well in regular irrigated soil.

2. Swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata), shown above, is a larval plant for the monarch butterfly and a fabulous bee plant. The honey bee, shown below with two bumble bees, comes from the TBG’s five beehives and the Oudolf entry garden is a rich nectar source for them.

This is the straight species of Asclepias incarnata with pink flowers and a nectaring carpenter bee (Xylocopa virginica).

3. Leadplant (Amorpha canescens) – The soft drift of leadplant in the Oudolf entry garden, below, was my first acquaintance with this lovely tallgrass prairie native,one of a few true Ontario natives in the garden. Its common name refers to the old belief that its presence indicated that there were lead deposits nearby, but that was disproven long ago. Its other folk names include downy indigobush (because it looks a little like indigofera) and buffalo bellows (because, to the native Oglala people who brewed it for a medicinal tea, it came into bloom when bison were in their bellowing-rutting season). A legume, it nitrifies the soil in which it grows (it’s usually considered a subshrub, rather than a perennial) and is one of the few natives that tolerates both dry soil and part-shade.

Bees love leadplant and its stamens provide a bright orange pollen. This is the brown-belted bumble bee (Bombus griseocollis).

4. Dense Blazing star (Liatris spicata) – One of the best tallgrass prairie natives for any sunny border, dense blazing star is no stranger to European gardens either, since it’s been available there in the cultivars ‘Kobold’ (shorter and darker purple than the species) and ‘Floristan Violet’ for decades. Like all Liatris species, it’s a great bee and butterfly plant and a good companion for echinaceas, including Piet Oudolf’s introduction below, ‘Vintage Wine’.

Mention is often made of ‘repetition’ in a Piet Oudolf design and this rhythmic syncopation of blazing stars across the vignette below illustrates how those magenta-purple spikes help carry the eye naturally from one side to the other.

5. Amsonias, Bluestars (Amsonia hubrichtii & Amsonia tabernaemontana var. salicifolia) – When I was writing my newspaper column in the mid-1990s, there was a sudden fuss about a genus of North American plants I’d never heard of. Amsonias were on the scene, and I planted Arkansas bluestar (A. hubrichtii) in my garden, which promptly turned up its toes and died. (It may have been a hardiness issue in an unusually cold winter, since this plant is native to the Ouachita mountains of Arkansas and Oklahoma.) Nevertheless, it gained traction in gardening circles and in 2011 was named the Perennial Plant Association’s Perennial of the Year. This is how it looks in the Oudolf border with late spring bulbs.

Arguably the brilliant yellow of the autumn foliage, below, is even more impressive than its ice-blue late spring flowers. Perhaps with our warmer winters, this species will continue to survive and thrive.

There are many species of Amsonia in commerce now, but willowleaf bluestar (Amsonia tabernaemontana var. salicifolia) is a good performer in the TBG entry garden and exceptionally hardy.

6.Joe Pye Weeds (Eutrochium sp., syn. Eupatorium) – The big Joe Pye weeds lend a powerful presence to the entry border in August and September, especially the statuesque ‘Gateway’ (Eutrochium maculatum) below. Given sufficient moisture, they thrive, last a long time in flower……

….. and attract myriad bees and butterflies to their dusty pink flowers.

7. Wild petunia (Ruellia humilis) – Native to dry prairie glades in Wisconsin, Illinois and regions south and west, this short, sprawling perennial has lilac-purple, petunia-like blossoms that are beloved by hummingbirds. Not showy, but a good little edge-of-path stalwart with a tap root. Self-seeds, too.

8. Anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) – One of the mainstays of Piet Oudolf’s designs is this aromatic North American Midwest mint family perennial with bee-friendly, lavender-purple flower spikes in mid-late summer. It spreads slowly by rhizomes.

Agastache foeniculum ‘Blue Fortune’ is an excellent selection with good winter presence.

9. Bowman’s root (Porteranthus trifoliatus, syn. Gillenia trifoliata) – One of the most beautiful pictures in the entry border is right at the end (or beginning, depending which way you’re walking) where the path intersects with the entrance to the Floral Hall Courtyard. Here, in June, a starry cloud of Bowman’s root or Indian physic rises behind a skirt of Japanese hakone grass (Hakonechloa macra). In its midst is a hybrid witch hazel which, though small now, will in time produce filtered shade under its boughs – and Bowman’s root is just fine in that light.

Here it is with a few neighbours: Geranium psilostemon and Hosta sieboldiana ‘Blue Angel’.

Special Plants

Sanguisorbas or Burnets – Piet Oudolf, more than any other plant designer, has made abundant use of the great genus Sanguisorba, the burnets. Hardy, reliable and taking up much less space on the ground than their tall, far-flung inflorescences do in the air, they are a much underused group of perennials. This is Sanguisorba tenuifolia ‘Alba’, or the white form of Chinese burnet, flowering alongside annual Verbena bonariensis.

Like Molinia caerulea ‘Transparent’, Chinese burnet is another good ‘screen’ or ‘scrim’ plant, even as its flowers fade. Here it is in front of Helenium autumnale ‘Fuego’.

This is the purple-flowered form of Chinese burnet, Sanguisorba tenuifolia ‘Purpurea’, growing in an attractive combination with Joe Pye weed (Eutrochium sp.)

Even the skeletons look strange and wonderful in autumn.

Burnets are good wildlife plants, attracting bees to their abundant pollen…..

…. and birds to their seedheads in autumn. In my little video below, sparrows are enjoying the seeds of Sanguisorba tenuifolia ‘Alba’, while American goldfinches are feeding on the seed of an unlabelled burnet I suspect is Sanguisorba tenuifolia ‘Pink Elephant’.

Birds & Bees

Speaking of birds and bees, as a photographer of honey bees, bumble bees and various native and non-native bees, I’d be remiss if I didn’t pay tribute to just a few of the great pollinator plants in the Oudolf entry border (besides the ones above, of course).

Calamint (Calamintha nepeta ssp. nepeta) – Calamint is, without doubt, the ‘buzziest’ bee plant there is. The sound is really something, with honey bees and bumble bees all over the tiny flowers – and there are tons of tiny flowers on this bushy little perennial.

‘Walker’s Low’ catmint (Nepeta racemosa) – Long-flowering catmints are superb bee plants, putting out nectar beloved by bumble bees and honey bees.

Wlassov’s cranesbill (Geranium wlassovianum) – Previously unknown to me, this little Asian geranium has become one of my favourites. Not only does it flower for an incredibly long time and prefer filtered shade, its flowers are always dancing with bees and its leaves turn red in autumn.

‘Robustissima’ Japanese anemone (Anemone tomentosa) – Japanese anemones are invaluable for their late summer-early autumn flowers, especially the singles like this lovely selection. And their stamens provide rich pollen at a time of year when bees are still looking to provision their nests.

‘Autumn Bride’ alumroot (Heuchera villosa) – It’s fun to watch honey bees working the tiny white flowers of this fabulous late heuchera.

Purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) – Echinacea and many of the selections are excellent bumble bee flowers, but they also provide abundant food for seed-eating birds like American goldfinch. A good reason not to cut down your perennial garden in late summer!

Seedheads

While we’re on the topic of seedheads, one of the hallmarks of Piet Oudolf’s design philosophy is the use of plants that perform beyond their flowering season, with persistent stems and seedheads that provide structure in the garden into autumn and winter. These are just a few of the entry border’s distinctive seedheads:

Swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) – The familiar chambered pods of milkweeds ripen, dry and split open in late autumn to reveal a layered arrangement of teardrop-shaped seeds topped by fine hairs. Over the next week or two, the seeds will gradually lift off on their silken parachutes, aloft on the wind to land on an empty inch of damp soil on which they’ll germinate the following spring. This is the milkweed life cycle that has evolved over millennia in all its regional species throughout North America in partnership with the monarch butterfly, whose females lay their eggs on the leaves, which then feed the developing caterpillar until it forms its chrysalis to emerge as the familiar orange-and-black butterfly we admire so.

‘Purpurlanze’ astilbe (Astilbe chinensis var. tacquetii) – I love the feathery bronze plumes of this Ernst Pagel-bred astilbe with the fountain grass (Pennisetum) behind.

Purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) – Long after the American goldfinches (above) have migrated south for the winter and the first snows have fallen, the raised seedheads of echinacea flowers still show their Fibonacci architecture.

‘Fascination’ Culver’s root (Veronicastrum virginicum) – The coppery wands of spent Culver’s root look beautiful against the tawny grasses of late autumn.

Plants That Go, Plants That Come…..

Not all of the original plants in the design thrived beyond a few years. One that was quite short-lived was the beautiful ornamental clover (Trifolium rubens), with dark pink flowers, below. In an ideal world, this plant would be allowed to self-seed, ensuring progeny for successive seasons. But it has petered out gradually.

Some of the yellow and orange hybrid echinaceas, like yellow ‘Sunrise’ shown in the early years with purple liatris, below, have also largely given up the ghost. Their lack of longevity (contrasted with the reliable long life of Piet’s Echinacea ‘Vintage Wine’) seems to be part-and-parcel of their genetic makeup, a fact Noel Kingsbury acknowleges in Hummelo: A Journey Through a Plantsman’s Life. “The 2000s saw a lot of breeding of E. purpurea with other Echinacea species, mostly in the U.S…… Some exciting color breaks – oranges and apricots – resulted, but the plants were mostly short-lived. For those wanting longer-lived plants, this breeding has not been of any use. We can only hope that someone picks up Piet’s work on longevity.”

Unlike a traditional perennial bed or mixed shrub-perennial border with a modest number of plants, a broad meadow planting like the entry garden with its huge cast of flowery characters is an open invitation to opportunistic plants, good and bad. With so many gardens (including a natural woodland) surrounding the entry walk, it was inevitable that seeds would fly into the rich, irrigated soil – either on the wind, or carried by birds. One of the immigrants – from the green roof of the administration building – is lovely foxglove penstemon, P. digitalis, a plant whose red-leafed form ‘Husker Red’ is used by Piet in his designs. Easy, prolific. drought-tolerant and a great bumblebee and hummingbird plant, this penstemon’s shimmering white spikes are quite lovely in June. It’s one of my favourite perennials.

But there are also seeds that may have been in the soil for many years, just waiting to germinate. Such is the case with common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), below, which I first spotted in my photos in 2011, four years after the garden was planted. Like Canada goldenrod, this is an aggressive native that spreads not only by seed, but by rhizomes underground. Beautiful and fragrant as it is, is difficult to maintain a small population. And given that the better-behaved swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) is here already and there are ‘wild’ places on the TBG property where common milkweed could be welcomed for its relationship to monarch butterflies, I hope it is kept in check so the design intent of the Oudolf garden is not lost.

Which brings me to maintenance. Toronto Botanical Garden currently operates on a financial shoestring. Unlike other popular parks and public places in Toronto, the TBG receives a pittance from the city. Hopefully, that will change in the near future as the City of Toronto Parks Department and the TBG conduct public consultations (two so far, one in November 2016, the last in late February) towards greatly increasing the size of the garden from the current 4 acres to 30 acres, placing all the current Edwards Gardens within a civically-supported Toronto Botanical Garden. However, at the moment, the head gardener works with just a few assistants and a changing team of volunteers to maintain not just the entry garden, but the other 16 gardens on site, and one or two off-site.

******************************

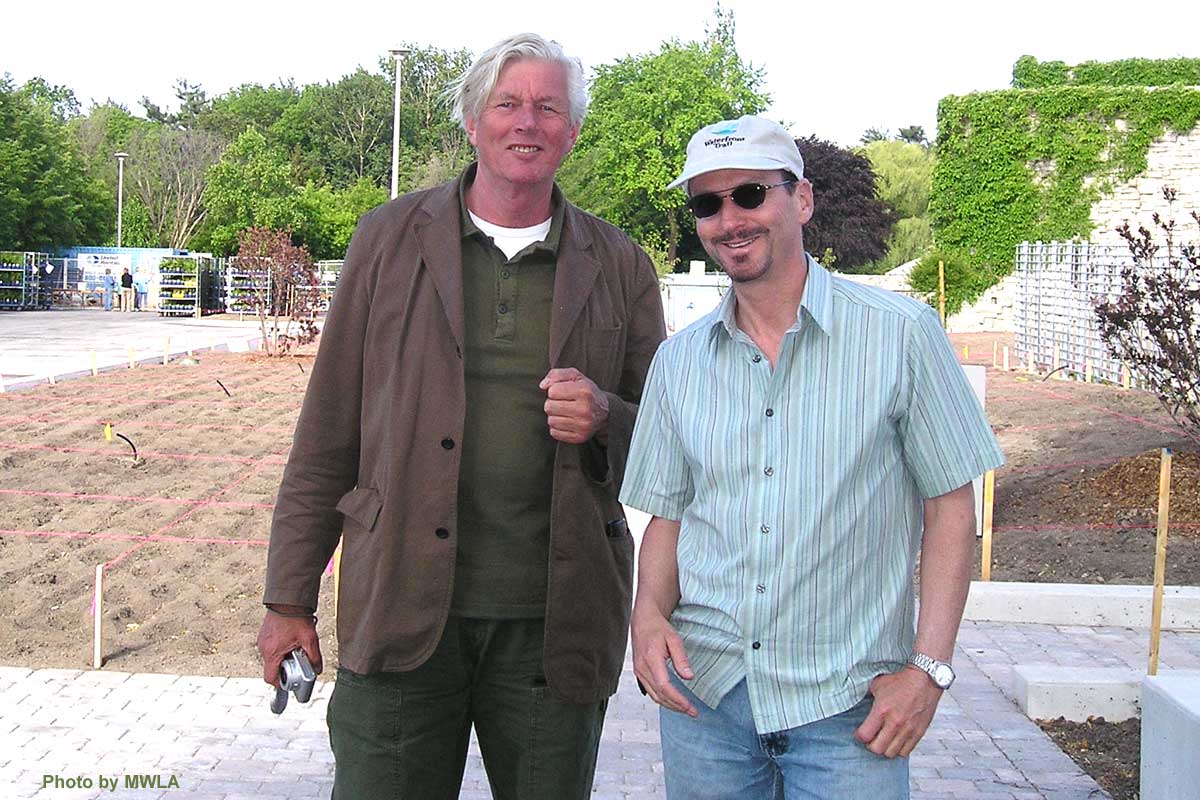

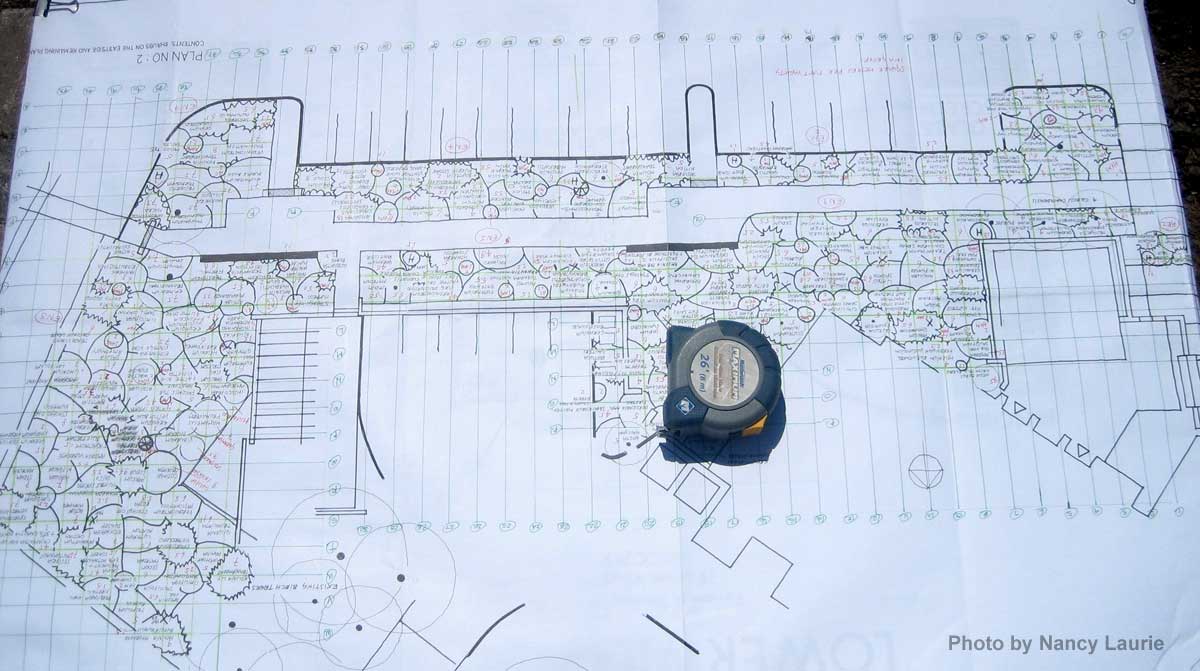

For perspective, I chatted with Toronto Landscape architect Martin Wade of Martin Wade Landscape Architects, below right, who collaborated with Piet Oudolf, left, on the design of the entry border, which was gifted to the TBG by the Garden Club of Toronto.

Martin fondly recalled their first meeting. “It was absolutely wonderful collaborating with Piet. He is extremely down-to-earth, humble and generous. I remember so clearly the very first time we met. After picking him up at the airport, we came back to our house where my partner was preparing dinner. It was shortly after we had moved in. I had not yet “done” the garden – it was a collection of plants left over from the previous owners. We were in the midst of a renovation and the place was in a bit of a shambles. IKEA curtains hung to cover exposed plumbing, bare sub-floor in some areas, and yet with all of this, it was somehow as though we had known one another for ages Piet sat down in a chair that had clearly seen better days and, over a single-malt whisky, the three of us talked about life in general and what our respective interests were. When I asked him what was important to him, he answered, without any hesitation, ‘Quality. Quality in terms of food, wine, art, relationships, architecture, landscape, virtually everything in life.’ The notion of quality as being the driving force that stimulates him has stuck with me.”

Martin & I talked about maintenance. Unlike Chicago’s 2.5 acre Piet Oudolf-designed Lurie Garden (Landscape Architects: Gustafson Guthrie Nichol), which cost $12.5 million and has a $10 million endowment for maintenance alone, the TBG’s entry garden has no separate budget for maintenance. Similarly, unlike the Oudolf-designed Marjorie G. Rosen Seasonal Walk at the New York Botanical Garden, below, a much smaller garden which has the equivalent of half-a-full-time employee dedicated to maintenance (including the hedge), there is no dedicated employee budgeted for the TBG’s Oudolf garden.

Before the entry garden was installed, Piet Oudolf, Martin Wade and the Garden Club of Toronto (GCT) had a frank discussion about long-term maintenance of the garden. By Piet’s estimate, the entry border would require a minimum of one full-time gardener dedicated to its upkeep. “As Piet explained,” recalls Martin, “His gardens, while ‘naturalistic’ and ‘meadow-like’ in appearance, are anything but low maintenance. They require regular tending to keep species that were not part of the original design out. I have noticed the invasion of common milkweed in the garden. This is a plant that has a host of great qualities and should be encouraged and let flourish in the right locations. However, it was not part of the original plan. The intent always was that the garden would be monitored yearly to ensure any of the more aggressive species in the plan were kept in check, and that the original plan be maintained, other than in the case of some species that just might not perform well, for which minor design adjustments would have to be made. This ‘monitoring’ process involves taking a copy of the plan in hand, walking throughout the garden, making note of what has crept into areas in which it was not meant to, and making adjustments accordingly.”

“Sadly,” he continues, “I don’t think the garden is achieving to the full extent the goals that were envisioned when the project began. I don’t mean this in any way as a criticism of the TBG or its staff, as I realize the extreme pressure they are under with respect to finances and resources that can be allocated to maintenance, not only of the entry garden, but all of their gardens. Maintenance is such a huge issue for all gardens, private or public, not only for the TBG gardens. It is relatively sexy these days to give a new building wing naming rights to honour the benefactor who helped make it a reality. The same applies to gardens. While a ‘sexy motive’ was not their intent, the Garden Club of Toronto was nonetheless very generous in gifting the Piet Oudolf/MWLA garden to the TBG. That is their mandate. The GCT funds public garden projects.”

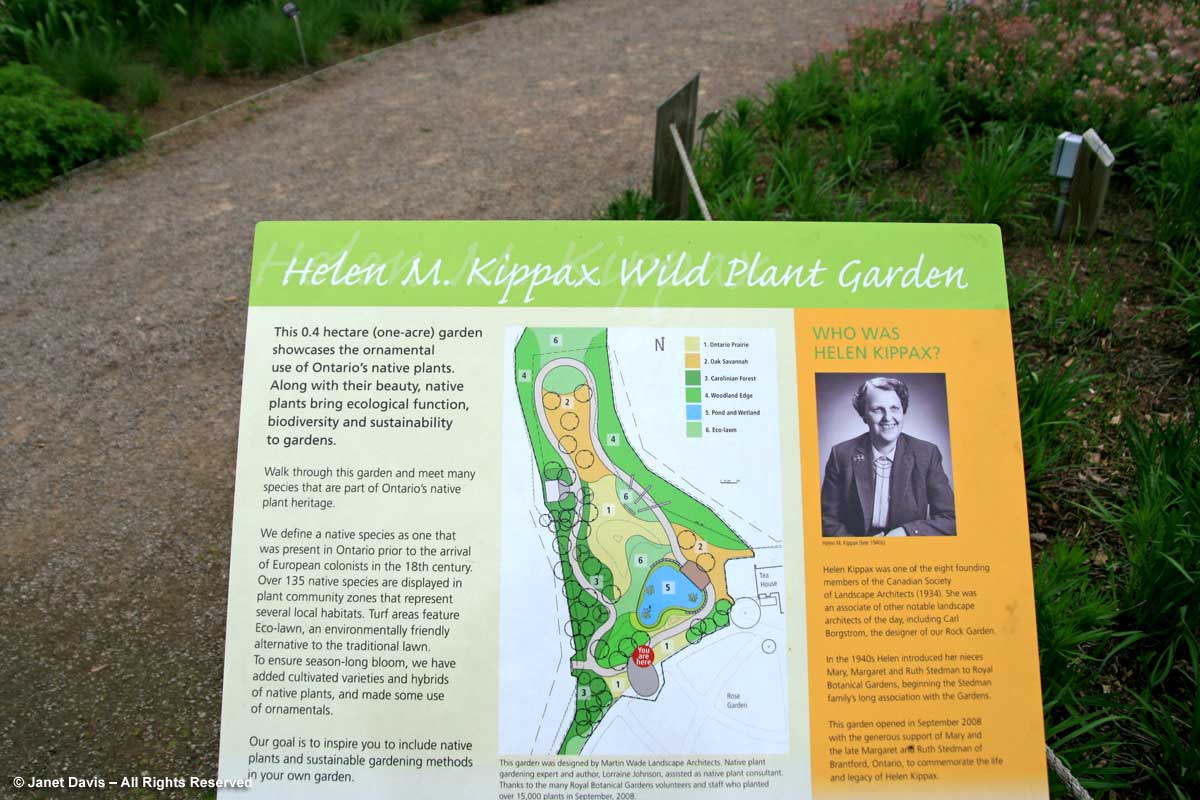

Martin cites another of his projects to illustrate the level of financial commitment needed. “Our firm designed the Helen M. Kippax Garden at the Royal Botanical Garden in Hamilton. The funds for this garden were donated by the late Mary Stedman in honour of her aunt Helen Kippax, one of the founding members of the Canadian Society of Landscape Architects. Ms. Stedman’s donation is suitably honoured by a plaque in the garden. She also had the foresight and financial ability to donate money to a trust fund, the interest from which is earmarked solely for the maintenance of the Kippax Garden. We need these types of visionaries, and institutions need to find a way to raise money not only for the installation of our public gardens, but for their long-term maintenance.”

*****************************************

But if the entry garden could use more a little more manpower to relieve the hard-working gardeners and volunteers, it is still, without a doubt, my favourite garden at the TBG. It takes me back to that childhood meadow I’ve carried in my heart for 60 years. It nourishes bees and butterflies and birds and the spirits of the visitors who walk the long path, flanked by a profusion of beautiful blossoms and swishing grasses.

And in case you haven’t taken that walk yourself, let me leave you with a beautiful memory of a warm August afternoon in the entry garden at Toronto Botanical Garden. Thank you, Garden Club of Toronto. Thank you, gardeners. Thank you, Martin Wade. And thank you, Piet Oudolf.