When we paused our tour of Chanticleer Garden outside Philadelphia in my previous blog, we were just leaving the shade-dappled woods and the creek garden. Let’s keep going now toward the ponds, where I stood behind one of the garden’s many cypress trees with a view all the way up the hill to the house, which you can just see at the top.

May 23rd is early for aquatic plants, so not much was in bloom yet….

… but the big koi swam toward me, perhaps hoping for a little fish food. I loved seeing the copper iris (I. fulva) at the shore, a native of southern swamps and wetlands.

Nearby was the carnivorous yellow pitcherplant (Sarracenia flava).

Yellow Thermopsis villosa was in bloom behind the big, bobbing heads of Allium giganteum. By mid-summer, the ponds are filled with water lilies and lotuses.

But I am a flower-lover at heart, and the gorgeous cottage garden display in front of the Arbor was calling my name.

The pink-flowered plant is showy evening primrose (Oenothera speciosa), a perennial wildflower native to the rocky prairies, meadows and open woodlands of Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska and neighbouring states.

One of the horticultural surprises at Chanticleer is the inclusion of tender plants, such as bromeliads and succulents, in the garden beds. This striking combination of tender Agave parryi (in a pot), Clematis Abilene and pink showy evening primrose caught my eye.

And I had never seen hyacinth squill (Scilla hyacinthoides) used so effectively in a northeastern garden!

This sunny, textural area at Chanticleer adjacent to the ponds and arbor is called the Gravel Garden, and it is the domain of my friend, horticulturist Lisa Roper.

One of the longest-serving employees, since 1990, she has been in charge of this particular garden and the neighbouring Ruin since 2013. She also does much of the photography for Chanticleer. We marked the occasion of my visit with a lovely photo, made by Chanticleer’s young Irish garden intern, Michael McGowan.

I first met Lisa back in 2014, when I photographed her trying out a penstemon in the mix of plants in a bed in the Gravel Garden. She works hard to get the mix of colours, textures and bloom times right.

And in 2018, she spoke at the Toronto Botanical Garden about this remarkable space at Chanticleer.

Back to the Gravel Garden, by late May the tulips and daffodils had finished blooming but there were still interesting bulbs to carry the eye through the garden, like the fuchsia-pink Italian gladioli (Gladiolus italicus) to the left of the gently ascending stone steps….

…. with its beautiful markings,

….. as well as foxtail lilies (Eremurus robustus) just beginning to flower…..

….. and, of course, the hyacinth squill (Scilla hyacinthoides).

Although the site is gently sloped, there are flat places along the journey through the garden…..

… and even a comfy place to sit, if you fancy a rather firm (concrete) cushion! That’s false hydrangea-vine (Schizophragma hydrangeoides) passing itself off as a fluffy, green throw on the sofa.

The spicy scent of the Dianthus ‘Mountain Mist’ was divine on that warm May Day. The orange flower is Papaver rupifragum with dark-purple columbines (Aquilegia vulgaris) to the left.

There are numerous stone troughs set along the path. This one contained Aloe maculata with ‘Elijah Blue’ fescue (Festuca glauca).

Century plant (Agave americana) was a strong focal point in a sea of self-seeding Orlaya grandiflora. This lacy, white-flowered annual is used extensively at Chanticleer.

Old-fashioned Italian bugloss (Anchusa azurea ‘Dropmore Blue’) was adding a vivid blue touch.

Even though the lighting is harsh, I loved this contrast: orange Spanish poppy (Papaver rupifragum) with Veronica austriaca ssp. teucrium ‘Royal Blue’ with purple and mauve columbines.

At the top of the Gravel Garden, we looked towards the wall of the Ruin Garden, which is also Lisa Roper’s responsibility. The salmon pink flowers are red valerian (Centranthus ruber ‘Coccineus’.) The shrub with white flowers at right is Chinese fringetree (Chionanthus retusus).

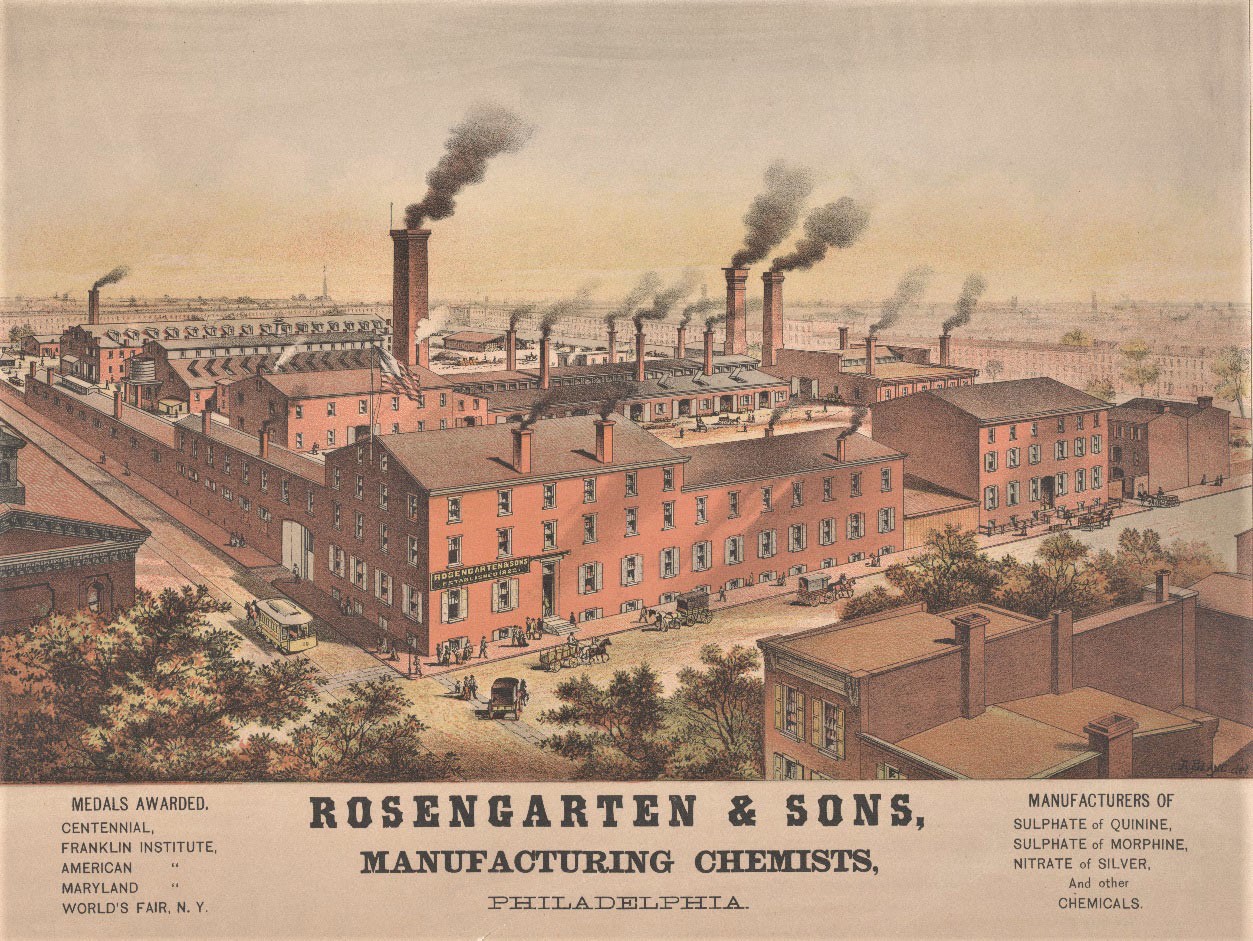

The Ruin is on the footprint of Adolph Rosengarten Jr’s (1905-90) former home, Minder House. (I wrote about “Dolph” in my first blog on Chanticleer in 2014.) With his sister Emily’s house serving as Chanticleer’s administration building and the main house in which Adolph Rosengarten Sr. and his wife Christine lived still standing, his house was deemed a better site for an evocative garden, so it was razed in 1999. Landscape architect Mara Baird created three stone-walled garden rooms. Here we see the library, with its fireplace.

Here’s the view from inside the Ruin Garden.

The succulents in the wall pockets are Agave attenuata ‘Ray of Light’. Climbing hydrangea (H. anomala subsp. petiolaris) is on the wall at left.

Although it was getting warm for the spring violas, I loved the tousled look of the floral mantel. The tree at left is the snakebark maple Acer davidii.

I really liked this bluestone trough with its exquisite plants: Agave mitis, Alluaudia procera, Aloe maculata, Echeveria ‘Perle Von Nurnberg’, Euphorbia characias ssp. wulfenii, Euphorbia tirucallii, Festuca glauca ‘Elijah Blue’ and Kalanchoe fedtschenkoi. I learned that by looking up the Plant List for the Ruin Garden!

San Francisco sculptor Marcia Donahue created the floating faces in the “Pool Room”.

I would love to have had the time to explore the Minder Woods beyond these pond cypress trees (Taxodium distichum var. imbricatum) as well as the Asian Woods I’d explored years earlier, but time was fleeting and a long drive north to Corning NY lay ahead of us.

So we headed down the slope toward the Great Lawn past this ebullient display of Allium ‘Globemaster’, oxeye daisies (Leucanthemum vulgare) and meadow sage (Salvia nemorosa ‘Caradonna’).

Further on, there was a chartreuse expanse of dyer’s woad (Isatis tinctoria)….

….. and the ice-blue amsonias that look so lovely in spring and again in autumn when the foliage turns golden-yellow.

In the wonderful book “The Art of Gardening” (Timber Press 2015) written by director Bill Thomas and the gardeners of Chanticleer and photographed by my friend Rob Cardillo, it says: “Spouses dragged here by the family garden-lover find we aren’t stuffy, and it’s actually not a bad place for a walk.” I would add that my husband Doug thought it was a great place to rest and enjoy the view after that walk!

Just beyond on the Great Lawn looking out over the Serpentine was another comfy chair in cool green.

Each year, the Serpentine features a different agricultural crop; this year it was red spring wheat (Triticum aestivum ‘MN-Torgy’).

Climbing the slope towards the house was a much more gentle and beautiful process than my last visit in 2014, with the new elevated walkway built the following year. I could have spent hours meandering up this curved steel walkway with its fabulous plantings.

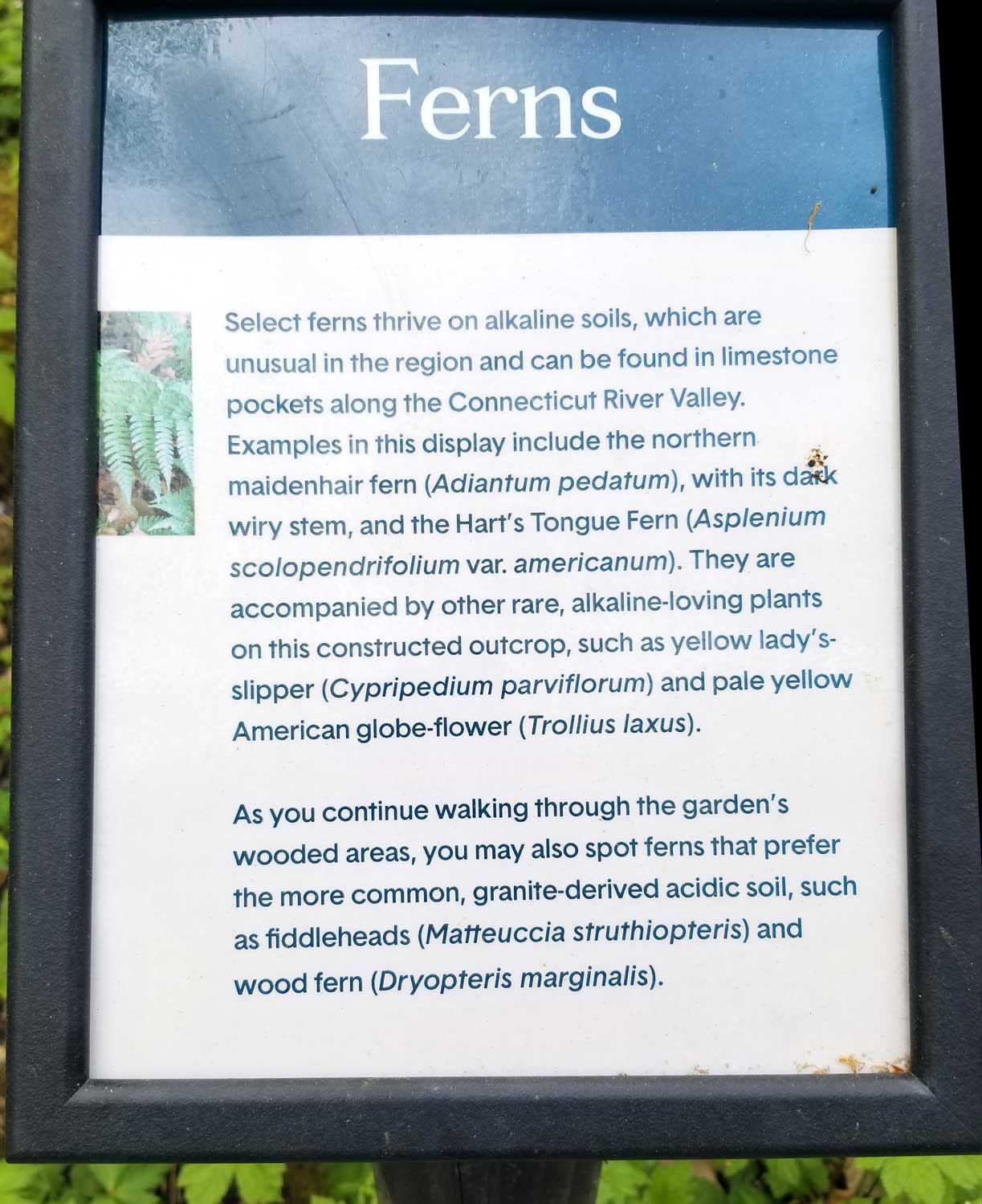

Have you ever seen so many columbines (Aquilegia canadensis)? Here they’re interplanted with ferns and many other perennials.

On the left is the honeysuckle Lonicera sempervirens ‘Major Wheeler’, on the right yellow Lonicera reticulata ‘Kintzley’s Ghost’.

Part-way up the elevated walkway was the Apple House, which had once been used by the Rosengartens to store fruit from their orchard.

I was surprised to see crossvine (Bignonia capreolata) growing on the walkway. It would certainly not be hardy in Toronto but perhaps it overwinters safely in Philadelphia.

Clematis montana var. grandiflora grew in a pretty tumble near the top.

Marcia Donahue’s cheeky rooster sculptures greeted me as I headed towards the house.

As always, the main house terrace was beautiful with its repeated chartreuse foliage and accents in teal-blue and lemon. The chairs were designed and built by Douglas Randolph.

As with all things Chanticleer, a visiting plant-lover could spend hours in each garden, just exploring the inspired plant choices. This is Japanese roof iris (I. tectorum); at rear is a pollarded Salix sachalinensis ‘Golden Sunshine’ with alliums, likely ‘Gladiator’ and Delphinium grandiflorum ‘Diamonds Blue’ peeking out from behind.

Behind the house is the swimming pool and pool house with plantings chosen to play off the colours of the water and copper roof. (In full sun at midday, this garden was hard to capture, but you can see the agaves, roses, etc. in my 2014 blog.)

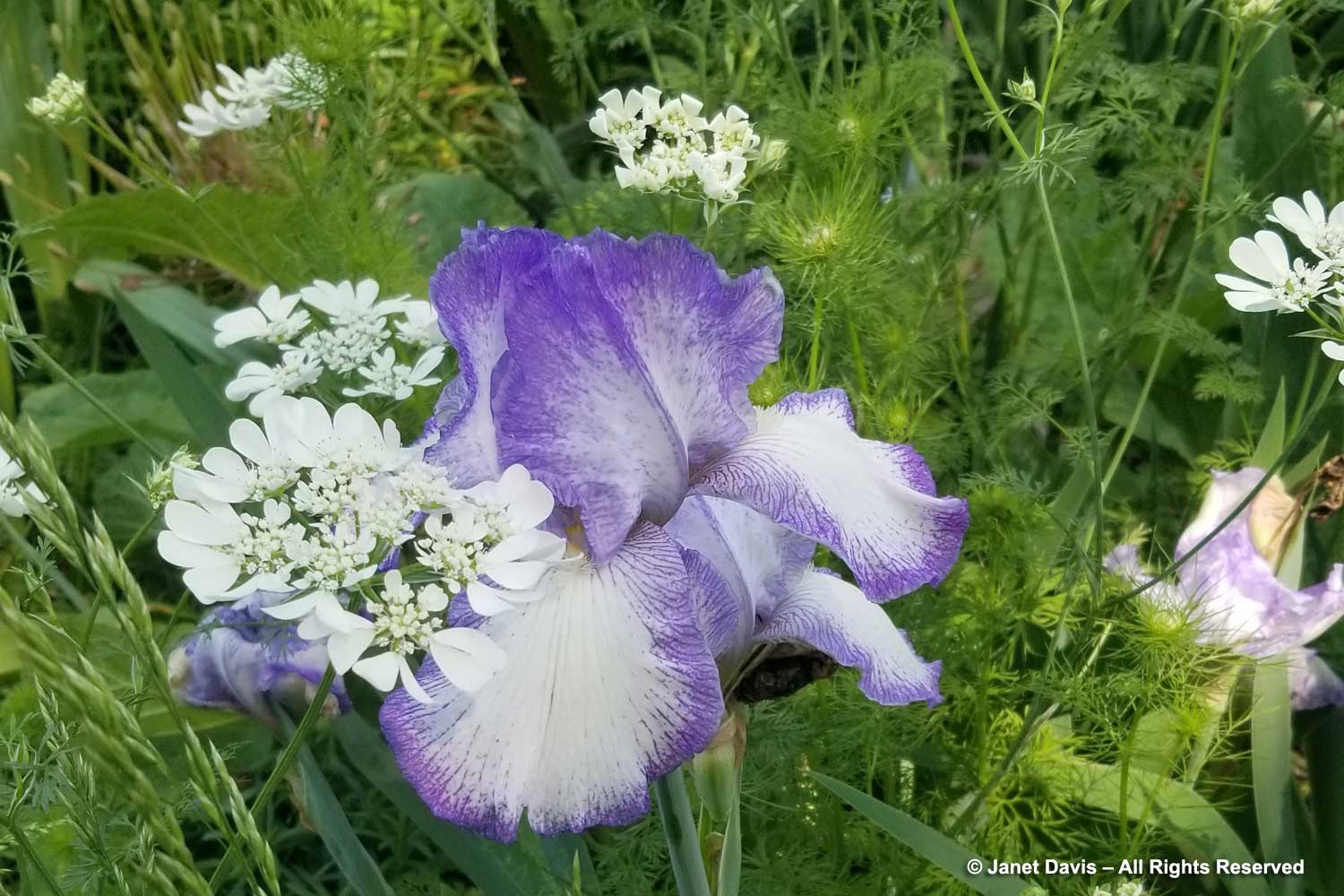

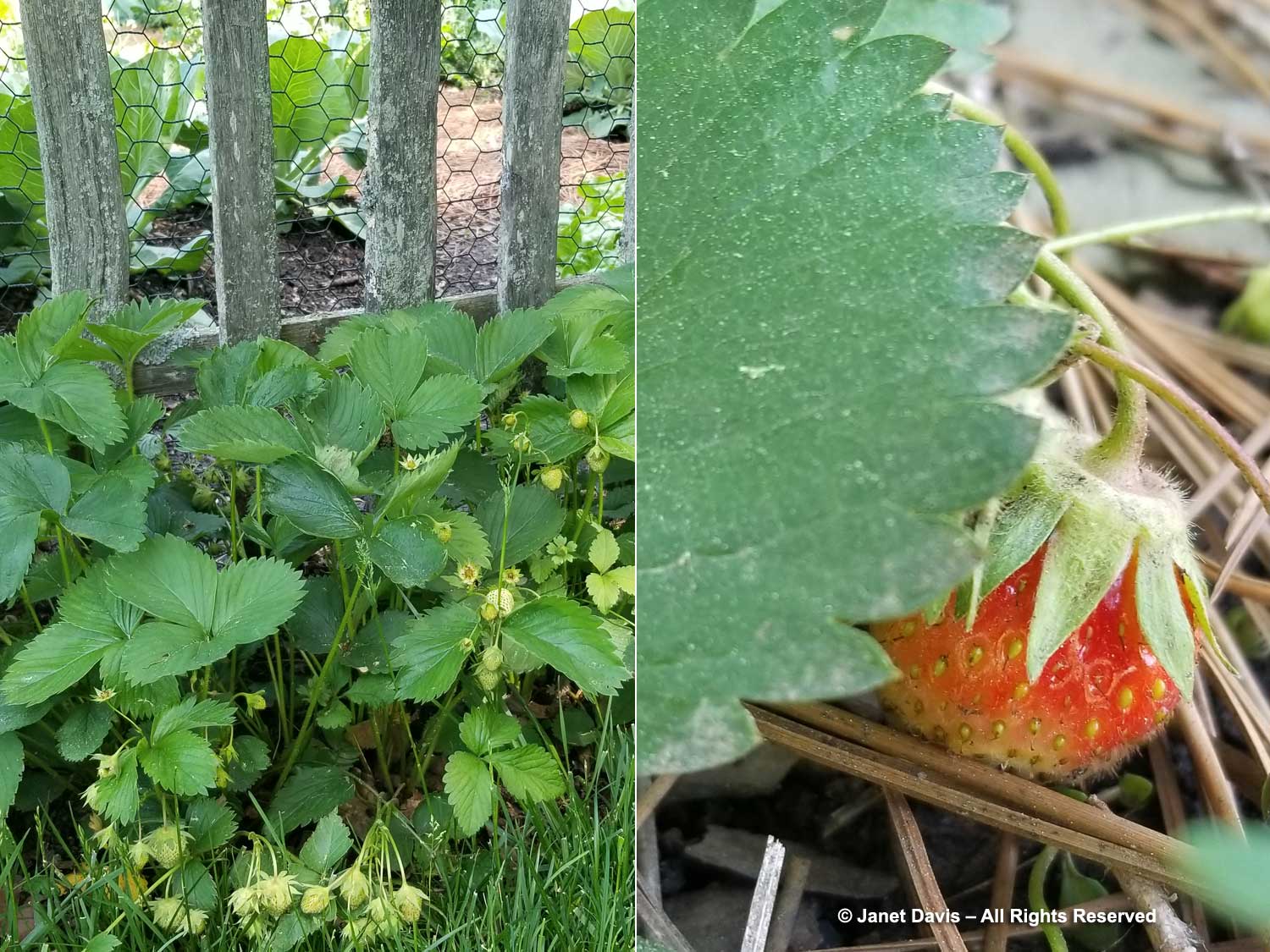

As a meadow gardener, the Flowery Lawn is one of my favourite places, with its enchanting, ever-changing cast of floral characters. You can see the bulb foliage now ripening in the midst of the purple ‘Gladiator’ alliums and biennial dame’s rocket (Hesperis matronalis). Here and there are scarlet ‘Beauty of Livermere’ Oriental poppies (Papaver orientale) and ‘Apricot Beauty’ foxgloves (Digitalis purpurea) with white orlaya and cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris). In summer, there’s anise hyssop and bachelor buttons here, part of a season-long parade of plants that enjoy this crowded scene.

Foxgloves and delphiniums (‘Magic Fountains Dark Blue Bee’) were at peak perfection in the east bed. Note the fennel and yellow snapdragons planted for summer bloom.

As we walked toward the parking lot to resume our road trip, I spotted this arresting combination – one of thousands of brilliant, carefully-considered pairings at Chanticleer. Look how the autumn fern (Dryopteris erythrosora) echoes the centre of the Itoh peony ‘Sequestered Sunshine’. It was just the last of countless reminders of why Chanticleer remains my favourite garden in North America.